The area now known as Zululand lies on the south-eastern coast of Africa, between the Drakensberg Mountains and the Indian Ocean. It is steep rolling grassland, dropping from cool inland heights to a sub-tropical coastal strip, and intersected by many river systems which have, in places, cut deep, wide gorges. In the valleys thornbush grew luxuriantly, and many of the heights were thickly forested. Until decimated by 19th century hunters, both black and white, the countryside teemed with game—antelope, wildebeest, elephant and lion. Above all, the area was covered with a wide mix of grasses which, with the comparative absence of tsetse fly, made it some of the best cattle country in southern Africa.

Cattle played a crucial role in the Zulu scheme of things, not just as a practical asset—a source of food and hides—but also as a means of assessing status and worth. Although African Iron Age deposits have been found across Zululand dating back to the 6th century, the Nguni people, the cultural and racial group to which the Zulu belong, wandered into the area in search of new pastures some time in the 17th century. They spread out over the countryside, slowly peopling it with clan groups who traced their origins to a common ancestor. Oral tradition has it that a man named Zulu established his homestead on the southern bank of the White Mfolozi River in about 1670. The name Zulu means ‘The heavens’, and his followers took the name amaZulu, ‘the people of the heavens’.

At this time the Zulus were no different from their neighbours. They lived in a series of village homesteads (umuzi; plural imizi) which were basically family units. Each village consisted of a number of huts built in a circle around a central cattle enclosure, and surrounded by a stockade. They were usually built on a slope facing east. The huts themselves were dome-shaped, like old-fashioned beehives. They were made by thatching grass to a wooden framework; the floor inside was made of polished clay, and a raised lip marked out the central fireplace. There was no chimney—the smoke escaped as best it could through the thatch. The layout of an umuzi reflected social relationships. The Nguni were polygamous, and a man might have as many wives as his wealth and status would allow. He himself lived at the top of the homestead facing the entrance with the wives and children of his senior house to the right, and those of the subordinate house to the left. Any dependents lived at the bottom, near the gate.

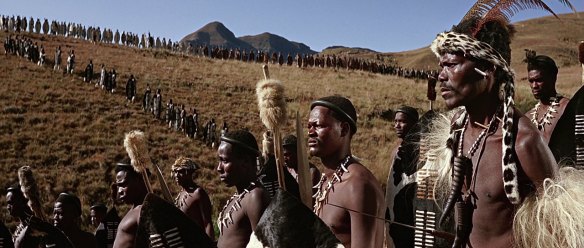

Army Organisation

The army was a crucial element in the system. It is difficult to arrive at reliable figures for the strength of Shaka’s army, but if it was 400 in 1816, 4,000 in 1818, and a maximum of about 15,000 when the great phase of expansion ended in 1824, its rapid growth is evident. The amabutho continued to be organised on an age basis, with youths of the same age being recruited from all the clans across the country. This reduced the risk, in such a conglomerate kingdom, of too many men from the same clan dominating a regiment, and being a potential source of dissent. Each ibutho was between 600 and 1,500 strong, and they were quartered in barracks known as amakhanda (sing, ikhanda), literally ‘heads’, which were strategically placed about the kingdom to act as centres for the distribution of royal authority. The amakhanda themselves were civilian homesteads writ large: there was a circle of huts around a central open space which served both to contain the regiment’s cattle and as a parade ground. They were surrounded by a stockade, sometimes a formidable barrier consisting of two rows of stakes leaning inwards so as to cross at the top, with the gap in between filled with thorn-bush. At the top of each ikhanda was a fenced-off section known as the isigodlo, where the king or his representatives would live when in residence. Each regiment had its own induna appointed by the king. In some cases female members of the king’s family were placed in charge of amakhanda.