‘If you wish to hoot and have a sword, drop the sword from your right hand, seize the wrist loop and slide it up the right forearm. Hold the bow and three arrows in your left hand. If you are on horseback and are also armed with a lance, push the lance beneath the right thigh. If you have a sword as well, put the lance beneath the left thigh. If a group of enemy halt out of range, disperse to shoot at them. If they come close, reassemble your forces. If you are near the enemy on a road, regroup to keep him on your left.’ (Murda al Tarsusi, ‘Book of Military Equipment and Tactics written for Saladin’)

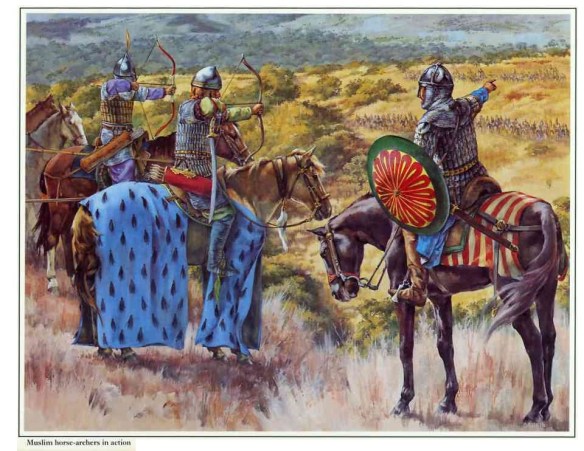

Documentary sources show that Muslim horse-archers used a variety of tactics including ‘shower shooting’ at a designated area or ‘killing zone’ rather than at an individual enemy. This was an essentially Persian tactic originally designed to cope with Turkish raiders from the Central Asian steppes in pre-Islamic times. The other most important form of horse-archery was Turkish in origin and involved shooting while the horse was in motion, either harassing an enemy from a distance or repeatedly charging and shooting. The aim was to get close, shoot at a range where the arrow would pierce almost any forn1 of protection, then retreat out of range of counter-fire.

Few unit exercises involved the bow; training in its use was largely an individual matter. The Middle Eastern tradition of horse-archery was based upon ‘shower-shooting’ in volleys, often while stationary. This tactic was more versatile than Central Asian horse-archery and needed less logistical backup. In the 10th century archers trained by shooting at a stuffed straw animal in a four-wheeled cart that was rolled downhill or pulled by a horseman. A fully competent 13th-century archer could reportedly shoot five arrows, held in the left hand with the bow, in two and a half seconds. Another five arrows were then snatched from a quiver.

Most archery training emphasized dexterity rather than accuracy. Nevertheless, a skilled archer was expected to hit a metre-wide target at 75 metres. (Closer-range archery training had a 60-metre training distance.) Training concentrated on three disciplines: shooting level, upwards or downwards, the latter two generally from horseback while moving. A horse-archer would probably have been able to loose five arrows at between 30 and five metres from an enemy when charging at full speed. He dropped his reins as he shot, but might use a strap from the reins to the ring-finger of his right hand to enable him to regain them quickly.

Shooting involved a sequence of skills: itar or stringing the bow; qabda or grasping the bow in the left hand; tafwiq or nocking an arrow in the string; aqd or locking the string in the right hand; madd or drawing back to the eye-brow, ear-lobe, moustache, chin or breastbone; nazar or aiming with any necessary corrections; and itlaq or loosing the arrow. Shooting was done in three ways: ‘snatched’ with the draw and release in one continuous movement; ‘held’ with a slow draw and a short pause before releasing; and ‘twisted’ with a partial draw followed by a pause then a snatched final draw and release. Men were advised to vary their techniques according to the tactical situation and to avoid tiring themselves.

Professional archers were trained to shoot from horseback, or standing, sitting, squatting or kneeling. They learned to shoot over fortifications and from beneath shields. There were several strengths of bow for different purposes, and they are distinguished by their draw-weights. A standard war weapon was from 50 kg up to a maximum of 75 kg. Three types of draw were used: the weak Mediterranean or European draw; the three-fingered daniyyat or Persian draw; and the powerful bazm or Turkish thumb-draw. A protective leather flap inside the fingers could be used with the Persian draw, and a protective thumb-ring with the Turkish thumb-draw.