The Jacobite débâcle at Sheriffmuir

Everyone knew ‘Bobbing John’, the Earl of Mar, was a politician who blew in the wind, but his timing happened to be perfect. By the time he raised James’s standard in 1715, other men of more confirmed will found they too had been pushed as far as they were prepared to go by vulgar Whigs and their notions of change. This time the great and the good flocked to his side as well, in stark contrast to Bonnie Dundee’s experience in 1689 when they had stayed away in droves.

From far and wide, great names and their warriors answered the call: Camerons of Lochiel, Campbells of Breadalbane and Glenlyon, Frasers, Gordons, MacDonalds of Clanranald, MacKenzies, MacLeans, MacLeods. The town of Inverness, too, rose in support of the Pretender. There were also many clans, Presbyterians like Gunn, MacKay, Munro, Ross, that stayed away, and the rising in the north-west was not uniform by any means.

Support for Mar was strongest in the Episcopalian north-east: Aberdeen declared for the Jacobites along with all the burghs north of the River Tay. In Brechin, James Maule, 4th Earl of Panmure summoned the populace in support of James VIII and III. James Carnegie, 5th Earl of Southesk rose too, as did James Ogilvy, soon to be Earl of Airlie, John Lyon, 5th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne and George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal of Scotland.

In that special way of civil wars, families were split across the Jacobite blade. John Murray, 1st Duke of Atholl and chief of Clan Murray, was a Hanoverian to the marrow of his bones. But three of his sons, Charles, George and William, declared for James and rallied an Atholl Brigade ready to fight alongside Mar. (George Murray – Lord George Murray – would later command the Jacobite army of the Young Pretender in 1745-6.)

Even when considering family loyalties – or the lack of them – there is room for confusing ‘what ifs’: wily chieftains were not above betting on both horses, and in some cases sons were commanded to fight on the opposite side from their fathers. By this strategy, the family estates would be retained by whoever ended up backing the winner.

With the sound of all these proud Scottish names ringing in the ears, it is all too seductive to imagine their only inspiration was patriotism. In truth, it was naked self-interest that drove many of the chiefs. The Camerons of Lochiel, like the MacLeods and the MacDonalds of Glencoe, had been unhappy since 1688. Having prospered under James VII and II, they had been cold-shouldered for more than a generation. Power had grown increasingly distant, centralised in far-off London. The return of the king meant the chance to reclaim past glory and influence.

The job of turning back the Jacobite tide fell to John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll and Scotland’s commander-in-chief. He was a military realist and realised that, while Mar was riding at the head of an army 10,000-strong, he himself had no hopes of gathering anything as great in the time available to him. The rising had also taken the Hanoverian government by surprise – in no small part because the disbanding of the Scots Privy Council had cost them their eyes and ears north of the Border.

Fortunately for Argyll, Mar vacillated as a general just as he had done as a politician. Though he was in command of a far greater force than that which would rise for Bonnie Prince Charlie thirty years later, though Episcopalian preachers were occupying Presbyterian pulpits and preaching rebellion, and despite the fact that Jacobites in the north of England were cheering him on – still he managed to make a mess of the whole affair.

Argyll had earned his spurs fighting for Marlborough during the War of the Spanish Succession and knew by training as well as by instinct what needed to be done. Stirling had always been the pinch-point through which any large force had to pass en route to the north or the south of Scotland. Wallace had exploited the fact in 1297, as had the Bruce in 1314. Argyll knew it too and while Mar hesitated at Perth he marched his force into position at Sheriffmuir, near Dunblane and close by Stirling itself.

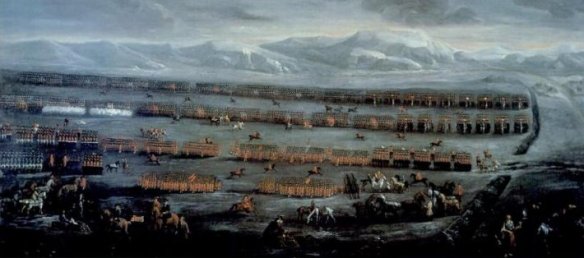

On 13 November 1715, one day before government troops would mop up the remains of the English rising at Preston, Mar finally confronted his foe. Argyll was outnumbered by at least two to one but he was a soldier against a dilettante. As it turned out, the battle itself was inconclusive, but it was Argyll who held the field at the close of play. Mar fled back to Perth.

Perhaps Mar’s initial indecision had stemmed from uncertainty about what the French would or would not do to back him. Since the death of Louis XIV France had been ruled by Phillipe duc d’Orléans, regent and great-uncle of the young Louis XV. Since he was conniving to have himself recognised as an heir to his nephew’s throne, Orléans had as much to gain but arguably more to lose through overt support of the Pretender. In the end he sent nothing and no one to aid Mar.

In late December, around the time when James himself was en route from Dunkirk to the port of Peterhead in belated support of his own rebellion, Philip of Spain put a fortune in gold aboard a ship bound for Scotland. The bad luck that was ever James’s travelling companion saw to it that the vessel was wrecked off St Andrews, its precious cargo soon to be scooped from the surf by jubilant Hanoverian soldiers.

James made landfall on 22 December but by then it was all over bar the shouting. For a few weeks he presided over a court of sorts at Scone, and by February was reduced to sending begging letters to Orléans, in hope of help that would never be sent. On the 26th of the month he boarded a ship at Montrose, along with Mar, and returned once more into exile.

In hindsight, the failure of it all seems astonishing. Had Mar been gifted with the merest sense of how to fight a campaign rather than just lead a parade, he could easily have moved past Argyll to link up with English Jacobites and Catholics in the north of England. The resultant momentum might well have brushed the Hanoverians from power, ready for James’s triumphant arrival. Instead, the government had been blessed by luck once more and the last real chance of Jacobite victory had passed.

The view from the twenty-first century is all very well but the fact is that in the aftermath of ‘The ’15’, the men of the British Establishment were badly rattled. They knew how close their regime had come to being overthrown, how big a part good fortune had had to play. But while they fretted about what James might do next, other forces – almost undetectable and probably unrecognisable as such to all but the most visionary – were starting to undermine the Jacobite cause in its very heartland, in Scotland herself. These were intellectual inquiry and the seeds of free market economy.

Just four years after the débâcle at Sheriffmuir, James would be drawn into another attempt to foment rebellion in the land of his fathers. This time the Pretender, Scotland and the Jacobites were mere pawns in a bigger game involving such disparate players as Spain, Sweden, Austria, Russia, Turkey and Italy.

This exploitation of Scotland, by far greater powers, was as cynical as it was half-hearted. Spain wanted to reclaim control of parts of Italy lost in the War of the Spanish Succession, but found herself opposed by Austria and Britain. As part of a plan of almost Byzantine complexity, Spain sought the self-interested collusion of the Russians and the Turks as well as the military might of crack Swedish troops led by their tactically brilliant King Charles XII.

It was really only Scotland’s geographical location facing Sweden across the North Sea that had brought her to the attention of the Spanish in the first place. Swedish ships were patrolling the water, prowling around after Hanoverian vessels. Since a Jacobite rising would be a useful irritant to throw in the face of an already preoccupied British government, opportunistic plans were duly laid. They culminated in James Francis Edward arriving in Spain in hopes of leading a venture as quixotic as anything ever attempted by the Man of La Mancha.

As things turned out, Spain was as far as he got. A combined Spanish-Jacobite force made a nuisance of itself in his name. Eilean Donan Castle was briefly garrisoned by Spaniards before being pounded to rubble by the guns of the British Navy. Spain had made noises about Jacobites rising in their tens of thousands, of wholesale rebellion, but it was cynical and empty talk. As could have been predicted, the whole dreamy fiasco arrived at a dead end – this time in a battle in the steep-sided valley of Glenshiel, on 10 June 1719.

All the assembled Highlanders could do was fight bravely, standing up to artillery and well-drilled Hanoverian musketry as well as any regular army could have done. But, as ever, it was not enough – could never have been enough – and Jacobite dreams blew away on the Highland breeze. James had never even put in an appearance and had stayed in Spain until advised by his hosts that his presence was no longer welcome.

His only success of 1719, and even that was qualified, was marriage to a woman who would bear him heirs. Maria Clementina Sobieski was the 17-year-old granddaughter of King John III Sobieski of Poland. Not only did she offer the prospect of producing more Stuart boys to continue the family line, she also brought a huge dowry including millions of French francs and a famous collection of family jewellery, the Sobieski Rubies. For a court in exile, therefore, she mattered every bit as much for her money as for her breeding capacity.

The marriage was an unhappy one and James a faithless husband, but it did deliver an heir. On 31 December 1720 Clementina gave birth to Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Silvester Severino Maria and, on 11 March 1725, Henry Benedict. Whatever other failings he might have had, whatever bad luck, James at least upheld that most notable tradition of Stuart men – the ability to make more of their kind. But while the Jacobite adventure was far from over, James Francis Edward would never again contemplate travelling to Scotland. As a wedding present from the Pope the couple had received a palace in Rome and it was there they stayed, where their boys were born and where the pale shadow of the Stuart court now took ineffectual root, a dynastic tumbleweed in search of moisture.

Of greater significance than the strength of James’s appetite for continuing the fight, however, was the advent of better times in Scotland. Far away from his baleful, backward-facing influence, Scots had begun to see at last the benefits of union with England.