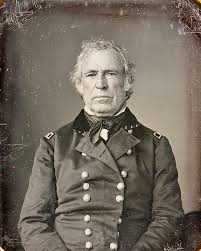

The Mexican War’s quintessential hero was Zachary Taylor, Old Rough and Ready. An obscure army colonel holding a brevet as brigadier general, with an undistinguished career behind him, sixty-two years old, Taylor burst upon the scene with unexpected suddenness in the spring of 1846. “There probably has never been . . . a time of such intense general excitement,” declared one writer, “as that immediately preceding the first engagement between the Americans and the Mexicans in the present war.” It was then that the nation looked, in a “moment of breathless anxiety,” to the Rio Grande and asked, “Who is General Taylor?” Authors, publishers, editors, correspondents, all scrambled to provide the answer. A race to produce the first biography of Taylor resulted in the almost simultaneous appearance of two books early in August 1846: C. Frank Powell’s Life of Major-General Zachary Taylor, carrying Taylor only through Resaca de la Palma, and the anonymous Life and Public Services of Gen. Z. Taylor, which ended with the occupation of Matamoros, a book that “should be in the hands of every citizen.”

It was only the beginning. Taylor was a man “neither Mexicans nor biographers” could put down. When it became apparent that he would achieve political as well as military fame, the number of works multiplied rapidly, some “mere catchpenny affairs” published in haste and showing it. Taylor, it was said, had more lives than a cat and one critic felt that the General could recruit an entire battalion out of the authors “who have attempted his life.”

Taylor sprang into fame “as a fabled personage of mythology came into being, the instant creation of a perfect hero.” He had served his country as a soldier for almost four decades, yet remained unknown. As a representative man and counter-agent to his times, Taylor appeared to be “the American whom Carlyle would recognize as ‘a hero’ worthy of his pen’s most eloquent recognition: THE MAN OF DUTY in an age of Self!” He was likened to Alexander, Caesar and Hannibal, Cromwell and Frederick the Great. Standing below medium height and inclined to corpulency, he recalled Napoleon. But it was to George Washington that Taylor was most often compared. Their lives, it was said, were parallel, their characteristics similar; indeed, to his generation Taylor seemed the “inheritor” of Washington’s virtues. In moderation, fairness, caution, fatherly regard for his troops, repugnance toward war, it was obvious wrote Walt Whitman, that “our Commander on the Rio Grande, emulates the Great Commander of our revolution.”

Americans did not have to look far to find the sources of Taylor’s heroism. The blood of some of the oldest and most distinguished families of Virginia flowed in his veins. His father had fought both British and Indians during the Revolution. Patriotism ran in his family and even showed in his face, as a practitioner of the new “science” of physiognomy pointed out. Nurtured on Kentucky’s “dark and bloody ground,” Taylor grew up in the woods. His nursery tales were stories of Indian butchery; as he grew older he heard often the “shriek of the maiden . . . the crack of the rifle . . . the fierce conflict between the father and his savage foe.” There was no better school for a warrior. “There is something in the very air of Kentucky which makes a man a soldier.” A man of the wilderness, Taylor imbibed the freedom, independence, and strength of the forest. He was, in short, of the same mold as Leatherstocking.”

Taylor’s character and personality were as important to his popularity as the victories he won in Mexico. Known affectionately as Old Rough and Ready or Old Zach or simply “the old man,” Taylor’s simplicity and lack of ostentation endeared him to the men under his command. Mounted on Old Whitey, wearing a large straw Mexican sombrero and a loose brown frock-coat his appearance belied his authority. His costume was so well known that he became known as the “old man in the plain brown coat.” Without visible indications of his rank, he was frequently mistaken for an aging private soldier. Those who saw him sitting alone in front of his tent, spectacles on his nose, mending his britches, could not believe that he was the “old hero, with whose name and fame the country was then ringing.”

The contrast between Taylor and his Mexican counterparts, in their brightly colored uniforms, gold embroidery, huge epaulettes, and collections of medals and ribbons, was so striking that witnesses could not resist drawing an analogy between the two nations they represented. The headquarters tent (or pavilion) of Mexican General Mariano Arista, overrun by American troops at Resaca de la Palma, seemed to be that of an Oriental satrap. The large gaily striped marquee housed richly figured ornamental chests, bright satin wall-hangings, intricate tapestries, and the General’s own personal silver plate. It was a “vision of a fairy land” to the open-mouthed soldiers who encountered it. Taylor slept in a regulation army tent with no outward markings to distinguish it from all the others; no sentinels were posted to screen the General’s visitors. Furnished only with camp stools and a couple of rough chests that served as a table, the tent was surrounded by an array of barrels, tubs, and pails, with Taylor’s favorite tin dishes and “good old coffee pot.” Only the presence of Ben, Taylor’s personal slave, revealed that the occupant was no ordinary soldier. The “semi-barbaric splendor” of Arista’s tent seemed to bespeak the pomp and despotism of the Mexican government, while Taylor’s abode reflected the democratic simplicity of America’s republican institutions.

Taylor’s insistence on being in the midst of battle and his coolness under fire matched his informality and served as inspiration to his men. Stories of his close calls abounded, many of them no doubt exaggerated. For example, measuring the speed and direction of an oncoming cannon ball at Buena Vista, Taylor rose in his saddle at precisely the right moment, allowing the ball to pass between him and his horse; when his coat was pierced by canister shot, he exclaimed, “These balls are growing excited.” True or not, Taylor’s apparent indifference to his own safety bolstered the confidence of the men around him. At Buena Vista he was described as “calm as a summer’s morning.” All eyes were turned toward him and “as long as he continued to rest easy, we were all satisfied, for never did Napoleon . . . possess in a more unbounded degree the confidence of his men and officers.”

The old General’s laconic remarks, uttered in battle were widely quoted. Some became legendary. Best known was his comment to young Captain of Artillery Braxton Bragg at Buena Vista, as Bragg brought his pieces to bear on the Mexican line: “A little more grape, Captain Bragg!” When an appeal was made for reinforcements to meet a Mexican charge, Taylor calmly replied, “I have no reinforcement to give you but Major Bliss and I will support you.” Both statements became important bits of Tayloriana, even though Bliss, Taylor’s adjutant, later insisted they were apocryphal. Some of Taylor’s remarks appeared in more than one version, and some were viewed as vulgar and profane, as when he urged his men to “stand to your guns and give them h—!” Taylor, however, prevailed and his terse, pithy statements evoked admiration and respect. During the war and after, “Give ’em Zack!” held unmistakable idiomatic meaning for Americans.

When Taylor returned to the United States in December 1847 he was received as a conquering hero. The citizens of New Orleans greeted him with one of the wildest and most lavish celebrations ever mounted in the Crescent City. Speeches of welcome, before thousands of people, were followed by a triumphant procession in which Taylor, spurning the offer of a carriage, rode on Old Whitey. Spectators plucked at the horse’s mane and tail for souvenirs. That evening, buildings were illuminated and transparencies were hung, depicting Taylor “in the old brown coat” and repeating his by now famous command to Captain Bragg. A sumptuous banquet followed at which toast after toast was drunk, each accompanied by appropriate music from a brass band. The festivities continued through the next day, and it was not until the third day finally dawned (a Sunday) that Taylor was able to journey up the Mississippi to the peace and quiet of his home in Baton Rouge.

Taylor’s heroism was celebrated not only in the outpouring of biographies and military histories. Engraved portraits by the score were executed and placed on sale; painters committed to canvas the record of Taylor’s achievements in Mexico; and statuettes were sculpted. “A great variety of portraits, of all ages, sizes, faces and costumes as diverse as imagination could paint them,” remarked the Scientific American, all purported to be “correct likenesses of Gen. Taylor.” Collected, the writer thought, the portraits “would form an interesting curiosity for a museum.” Countless poems, from humorous doggerel to effusive sentimental verse, appeared in books, newspapers, and magazines; and music, such as General Taylor’s Gallop, General Taylor’s Grand March, General Taylor’s Quick Step, and the Rough and Ready Polka, was composed, sold, and performed. Taylor’s sobriquet became a household phrase: Post and Lemon’s Manhattan Fresh Milled Effulgent Horse-Radish Sauce adopted the motto “Rough and Ready” (“Our Country, Horse- Radish and Liberty!”); straw bonnets became known as “Rough and Ready straws”; boots and shoes were advertised as “Rough and Ready.”