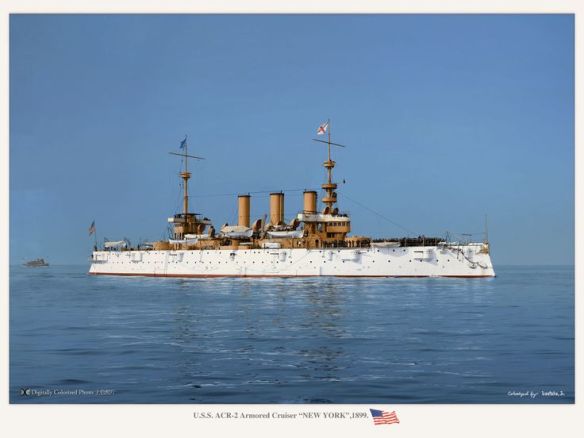

The U.S. Navy armored cruiser New York, flasghip of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson’s North Atlantic Squadron. (Photographic History of the Spanish- American War, 1898)

Beginning in the mid-1880s, the U.S. Navy had undergone a dramatic transformation. Although still small by European standards, the navy began receiving modern steam-driven steel ships armed with modern breech-loading rifled ordnance. The intellectual underpinnings of U.S. naval strategic thought came principally from the writings of naval historian and strategist Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. In his landmark work The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (1890), he postulated that world power rested on sea power. He eschewed the traditional U.S. Navy strategy of a guerre de course (war against commerce) in favor of a battle fleet capable of winning control of the sea. Such a task could only be accomplished by battleships operating in squadrons. To support the projection of naval power, the United States would need overseas bases and coaling stations. Among Mahan’s admirers were President William McKinley and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt. They along with others within the administration, many in Congress, industrialists, and leaders from many segments of American society pushed for naval expansion to be concentrated in capital ships. It was this new American navy that made possible the victory over Spain in 1898.

With tensions increasing between the United States and Spain over Cuba, the U.S. Naval War College developed a strategy for fighting a naval war with Spain. This strategic plan was revised annually right up to the beginning of the Spanish-American War. In addition, the Navy Department also drafted contingency plans for a conflict with Spain. Some contingency plans envisioned a war that would involve fighting the combined navies of Spain and Great Britain. Seizure of Cuba from Spain, however, was at the center of planning in the half decade before the war.

At the beginning of the war, the immediate Spanish threat came in the form of Spanish rear admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete’s squadron of two cruisers and four destroyers. The U.S. public grossly exaggerated the squadron’s actual power, and there were loud calls from alarmists in East Coast cities for ships to protect them from a Spanish naval blockade or even attack. Such action was utterly beyond Cervera’s means. In any case, the manning of coastal forts, armed for the most part with obsolete ordnance, helped to quiet fears, as did a compromise naval strategy.

The Navy Department was determined that the North Atlantic Squadron should be kept together in keeping with Mahanian principles. No matter where Cervera might appear in the Caribbean, the Atlantic Squadron would thus be able to mount a retaliatory strike. To quiet East coast anxieties over Cervera, however, the Navy Department agreed to a compromise arrangement. While the bulk of U.S. naval strength was still concentrated in the North Atlantic Squadron under Rear Admiral William T. Sampson based at Key West, Florida, for a descent against Cuba, part of Atlantic naval strength was formed into the Flying Squadron, under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley, to serve as a mobile protection force for the vulnerable Atlantic seaboard. In addition, a small Northern Patrol Squadron of obsolete warships was organized to defend the coast from the Delaware Capes northward.

On April 22, 1898, the Navy Department ordered Sampson to establish a naval blockade of Cuba. On April 25, Congress declared that a state of war had existed since April 21. Initially, the U.S. blockade was to extend from Havana around the western tip of Cuba as far as Cienfuegos on the southern coast of the island. It was later extended as more ships became available. The blockade was designed to prevent Spain from supplying or reinforcing its sizable military strength in Cuba while the United States prepared its own invasion forces. In the war at sea, the United States enjoyed a tremendous geographical advantage over Spain. U.S. ships on Cuban station could be easily resupplied from nearby Florida ports, whereas to reach that island the Spanish ships would have to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Meanwhile, on April 29, Admiral Cervera departed Cape Verdes for Puerto Rico and eventually found his way to Santiago de Cuba.

U.S. secretary of the navy John D. Long left naval deployments and planning largely up to Roosevelt, who ordered an aggressive strategy for the Pacific theater of war. Roosevelt cabled Commodore George Dewey, commander of the small U.S. Navy Asiatic Squadron of four cruisers, two gunboats, and a revenue cutter, directing that in the event of hostilities with Cuba, Dewey was to mount offensive action against the Spanish squadron in the Philippine Islands. When war came, Dewey immediately steamed the 600 miles to the Philippines and in the Battle of Manila Bay (May 1, 1898) destroyed the Spanish squadron of Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. After taking the Spanish naval base at Cavite, Dewey then blockaded Manila to await the arrival of ground troops.

In the Caribbean theater, meanwhile, the U.S. Navy steadily built up its naval strength, assisted by the eventual arrival of the battleship Oregon from the Pacific coast. The navy not only maintained a blockade of Cuba but also cut cable communications with Spain and supplied Cuban insurgent forces ashore. Sampson wanted a descent on Havana, believing that the U.S. capture of the Cuban capital city would bring the war to a close. Long disagreed, citing the facts that the army was unready for an amphibious operation, that the Atlantic Squadron was divided between Norfolk and the Caribbean, that Cervera’s Spanish squadron was still at large, and that the U.S. warships would be at risk from Havana’s shore defenses. The new Naval War Board agreed.

Meanwhile, there was the problem of Cervera. Guessing that the Spanish admiral would head to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to coal, Sampson partially lifted the naval blockade of Cuba on May 3 and made for that island with two battleships, a cruiser, two monitors, and a torpedo boat. Slowed by the monitors, which had to be towed, he did not arrive off Puerto Rico until May 19 and then contented himself with a brief bombardment of the San Juan shore defenses, inflicting little damage. Mahan, who condemned Sampson’s move, had advocated only the dispatch of scout cruisers to provide warning of Cervera’s arrival. They could then notify Sampson. Only then, Mahan believed, should Sampson venture forth with his squadron to seek a decisive encounter.

As it turned out, Cervera outguessed Sampson and slipped undetected into Santiago on Cuba’s southern coast on May 19. Meanwhile, Schley, sent by Sampson to locate Cervera, wasted valuable time at Cienfuegos in the belief that Cervera might be there. Schley did not arrive at Santiago until May 28, and he was soon joined by Sampson and the remaining ships of the North Atlantic Squadron. Although the U.S. Navy’s June 3 attempt to scuttle the monitor Merrimac failed to block the narrow channel into Santiago Harbor, Cervera remained quiescent, allowing the U.S. Navy to blockade Santiago.

With Cervera bottled up at Santiago, the U.S. invasion of Cuba could proceed. Still, the U.S. Navy demanded that the army invade at Santiago and do so quickly in order to destroy Cervera’s squadron. U.S. strategic thinking now shifted definitively from Havana to Santiago. On June 22, members of the army’s V Corps Expeditionary Force under Major General William R. Shafter began coming ashore at the port of Daiquirí, some 16 miles east of Santiago. Although Shafter wanted the navy to shell the forts, steam up the channel, and engage Cervera’s ships at Santiago, Sampson held that this was impossible given the Spanish shore batteries and threat of mines in the narrow channel. He wanted Shafter’s troops first to attack and reduce the shore batteries at the mouth of the channel. Despite Sampson’s belief that there was agreement on that course of action, Shafter moved inland to attack Santiago itself. In any case, following U.S. victories on land on June 1 and the closing of the U.S. ground force on Santiago, on July 3 Cervera finally attempted to escape Santiago de Cuba to sea. The ensuing naval battle at Santiago de Cuba resulted in the utter destruction of his squadron by the far more powerful U.S. blockaders. The other factor in the defeat was the fact that the Spanish ships had to exit the narrow harbor mouth in single file, making them vulnerable to American fire one at a time.

With the Spanish naval threat gone and with Santiago having surrendered, the navy then transported an army expeditionary force to Puerto Rico. Meanwhile, the threat of a Spanish naval squadron under Rear Admiral Manual de la Cámara y Libermoore, consisting of a battleship, three cruisers, and two transports lifting 4,000 troops and dispatched from Spain to the Philippines by way of the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal, evaporated when it was called home from the Red Sea. Dewey maintained a blockade of Manila Bay and, with the arrival of U.S. ground forces, assisted the army in the capture of Manila in August. The war ended on August 12, 1898, with the United States in possession of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. In the subsequent fighting of the Philippine- American War, the navy provided valuable assistance to army operations ashore, including the conduct of amphibious operations.

Further Reading LaFeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1963. Livezey, William E. Mahan on Sea Power. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1947. Schoonover, Thomas. Uncle Sam’s War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003. Seager, Robert. Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Man and His Letters. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1977. Trask, David F. The War with Spain in 1898. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.