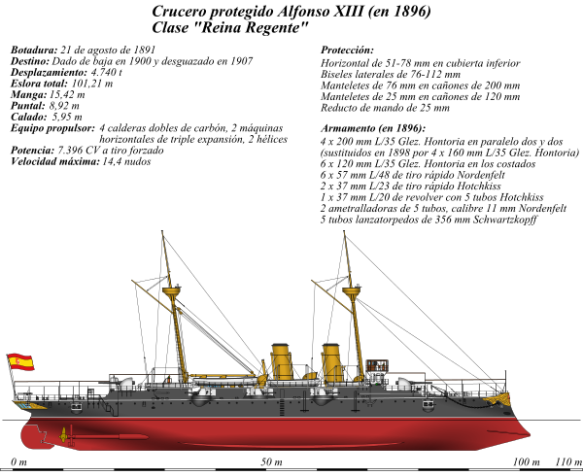

The Spanish Navy protected cruiser Alfonso XIII. (Photographic History of the Spanish-American War, 1898)

When news of the American blockade of Cuba reached Madrid, large numbers of Spaniards clamored to enlist in the navy. Convinced of Spanish naval strength following more than a decade of showy reconstruction and foreign purchases, many Spaniards pressed for its immediate employment. These sentiments were echoed by many politicians in the Cortes (parliament) and throughout the civilian administration.

Pundits and opinion makers expected Rear Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete to sortie immediately with his squadron from the Cape Verde Islands and challenge the U.S. Navy in the Caribbean. Many Spaniards believed that while the Americans were distracted in the Caribbean, the navy could also easily raid the vulnerable U.S. Atlantic seaboard. General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, who had been recalled to Madrid by the queen regent, even glibly proposed that 50,000 Spanish troops be disembarked to wreak havoc along the U.S. eastern shoreline.

Such grandiose schemes, of course, went well beyond the capabilities of the Spanish Navy. Spanish professional naval officers realized that although numerous, few of their warships were capable of campaigning effectively on the high seas against their more powerful American opponents. Set-piece battles against an enemy fleet were not part of the Spanish Navy’s mentality or training. Indeed, the Royal Spanish Navy’s defensive strategy had been codified as early as 1886 by naval minister Vice Admiral José María Beránger.

When current minister Rear Admiral Segismundo Bermejo y Merelo, in office scarcely seven months, bowed to political pressure and reluctantly drew up orders for Cervera to steam to the Caribbean, he attempted to deflect the public clamor for his squadron to charge headlong into battle. Indeed, Cervera was to proceed stealthily toward the sanctuary of San Juan de Puerto Rico, avoiding any unfavorable clashes at sea. He was also authorized to proceed on to Cuba, depending upon the situation.

To Cervera, even such modest goals seemed ill-advised. After meeting with his officers, he cabled back a proposal that his warships proceed no farther than the Canary Islands, taking up station there so as to steam to the aid of any threat against Spain itself. In proposing this strategy, he pointed out that U.S. naval forces were “immensely superior in number and class of ships, armor, and gunnery, as well as in state of readiness” to his own problem-plagued command.

Yet such a timid course as Cervera proposed was impossible for political reasons, so Bermejo’s initial orders were repeated. At midnight on April 29, 1898, Cervera slipped out of San Vicente in the Cape Verde Islands with his four cruisers, three destroyers, and a hospital ship. While running across the Atlantic, he learned that Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón’s squadron had been destroyed in the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1 and that the shore batteries guarding San Juan, Puerto Rico, had been shelled by Rear Admiral William Sampson’s powerful North Atlantic Squadron. Therefore, with considerable skill and good fortune, Cervera was able to coal at Curaçao and steal into Santiago Bay on May 19.

Only the day before, Bermejo had been compelled to resign as minister of the navy amid a great public outcry against the unexpected Spanish defeat at Manila. In order to mitigate the recriminations being hurled against the navy’s disappointing performance, the notion of attacking the U.S. eastern seaboard was revived. Although a full-scale invasion was clearly impossible, it was suggested that a pair of transatlantic sorties might be launched. While no significant strategic advantage could realistically be achieved by such a feat, naval professionals at least consoled themselves that the distraction might ease some of the American pressure on blockaded Cuba.

Thus, Captain José Ferrándiz was ordered to prepare to strike out in the direction of the Caribbean with his aged battleship Pelayo plus the even older coast guard vessel Vitoria and the destroyers Osado, Audaz, and Proserpina. This sortie was to be merely a feint, though, as all five were to quickly reverse course and return to Spanish waters and assume coastal patrol.

The real thrust was to be made by Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Libermoore, who under cover of this initial diversion was to slip out for Bermuda with his armored cruiser Carlos V accompanied by three fast, lightly armed liners that had been converted into auxiliary cruisers—the 12,000-ton Patriota, 11,000-ton Meteoro, and 10,500-ton Patriota—as well as the dispatch vessel Giralda. After coaling at Bermuda, this strike force was to ply the eastern seaboard of the United States as commerce raiders, wreaking as much havoc as possible, while working its way northward into Canadian waters. From Halifax, Admiral Cámara’s small force was then to head east into the Atlantic as if returning to Spain before actually veering south to emerge amid the Turks and Caicos islands for more interceptions of American ships.

Finally, anticipating that U.S. naval forces would be obliged to redeploy into the North Atlantic to hunt for this elusive force, a second small squadron of commerce raiders was to steam from Spain under Captain José Barrasa. With his aged cruiser Alfonso XII plus the auxiliary cruisers Antonio López and Buenos Aires, he was to make landfall near Brazil’s Cape San Roque, then prey upon the busy American ship lanes rounding South America.

Yet all these offensive notions were scrapped when it was learned that the United States intended to dispatch an expeditionary force to occupy the Philippines. Hoping to beat them to the archipelago, Spanish naval strategy turned around completely. Admiral Cámara was ordered to convoy transports carrying 4,000 troops to the Philippines. This Spanish force was to move through the Suez Canal so as to arrive in Philippine waters prior to the U.S. invasion army and disembark the Spanish troops on the islands of Jolo and Mindanao to spearhead a local resistance.

Cámara’s original 13 vessels were to be augmented by the transport Isla de Panay as well as the colliers Colón, Covadonga, San Agustín, and San Francisco, the latter four ships because the only reliable supplies of coal for the Spanish squadron would be found at the neutral Italian ports in Eritrea as well as French ports in Indochina. Accompanied by the dispatch vessel Joaquín del Piélago, Cámara’s lumbering squadron reached Port Said, Egypt, by June 22, 1898, only to be delayed in gaining access to the Suez Canal.

Meanwhile, political pressure continued to mount in Madrid regarding the navy’s lackluster performance, with feelings running especially high against Cervera’s lengthy stay inside Santiago Bay. Fearful that the anchored Spanish warships would be forced to surrender without firing a shot once Santiago fell to its American besiegers, yet another new and hard-pressed navy minister, Captain Ramón Auñón y Villalón, ordered Cervera’s squadron to sortie. Fully as Cervera had predicted, it was annihilated after exiting the harbor on July 3. This shocking loss collapsed public morale and also led to the recall of Cámara’s expedition from the Red Sea. The Philippines had been openly abandoned to U.S. seizure, soon to be followed by Cuba and Puerto Rico, as Spain could only look on helplessly.

If allowed to pursue their prewar strategy, the high command of the Royal Spanish Navy would have preferred to fight a defensive struggle, sortieing occasionally from their fortified harbors with single ships or swift, small squadrons to make a sweep or to relieve a beleaguered outpost. Instead, unrealistic expectations generated by public opinion and pushed by the politicians had resulted in demands for a naval strategy that the professional navy did not want and could not perform.

Further Reading Almunia Fernández, Celso Jesús. “La opinión pública española sobre la pérdida del imperio colonial: De Zanjón al desastre (1878–1898)” [Spanish Public Opinion toward the Loss of the Imperial Colonies: From Zanjon to the Disaster, 1878–1898]. Imágenes y ensayos del 98 (1998): 205–252. Calvo Poyato, José. El Desastre del 98 [The Disaster of 1898]. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1997. Cervera Pery, José. La guerra naval del 98: a mal planeamiento, peores consecuencias [The Naval War of 1898: Poor Planning, Worse Consequences]. Madrid: San Martín, 1998. Feuer, A. B. The Spanish-American War at Sea: Naval Action in the Atlantic. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1995. Smith, Joseph. The Spanish-American War: Conflict in the Caribbean and the Pacific, 1895–1902. New York: Longman, 1994.