George Majeska

The Beginnings

Relations between Rus’ and the Byzantine Empire centered at Constantinople (modern Istanbul) were not always friendly. Already in the early ninth century, Viking Rus’ had apparently pillaged the Byzantine city of Amastris on the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, and by the 830s the Byzantine government had converted the province of Cherson in the Crimea into a military region. Its apparent goal: to control Rus’ predations on the Black Sea, as well as to protect the city of Cherson (Chersonesus, Korsun) itself, an important transshipment port of grain for the Byzantine capital.

Perhaps it was to negotiate some sort of peaceful relationship between the Byzantines and the Rus’, most likely a trade agreement, that Rus’, envoys appeared in Constantinople in 838–9. Whatever the reason for their mission, they ould not return home the way they came (via the Black Sea, it would seem, and through the steppe where there was serious nomad military activity) and were dispatched home through Germany.

In 860, for reasons we do not know but probably to pillage, Viking Rus’ (the leaders of the early Rus’ state were Scandinavian Vikings) attacked Constantinople with two hundred ships. There had been no warning. The emperor was with his army on the Empire’s eastern frontier and the navy was also occupied in fighting the Arabs. Only the stout walls of the Byzantine capital kept the invader out of the city itself. According to Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople, who essentially took charge of the besieged city in the emperor’s absence, the Rus’ attackers pillaged the suburbs mercilessly, killing many, even women and children, before they suddenly withdrew homeward, leaving the area before the emperor returned with his army. Later sources would attribute the Russian retreat to a miracle performed by the Mother of God in order to save the Christian city from the pagan Rus’. The Rus’ attack must have been formidable to force the Emperor to leave the eastern frontier. It is unclear from where the Rus’ strike force came. Although it is possible that it came from some other Viking Rus’ settlement in the north, it is probable that the attack was launched from a Viking Rus’ trading colony near the mouth of the river Don, the most likely point of origin for a flotilla of two hundred ships. The Kievan Rus’ state as we normally think of it did not yet exist. The Byzantine response to this new threat of the Rus’ was twofold. First, the Byzantines firmed up their alliance with the Turkic Khazars, who dominated the Russian steppe through which Rus’ would have to move on their way to Constantinople. Second, Patriarch Photius sent missionaries to convert the Rus’ to Byzantine Christianity, a conversion that would supposedly make them more friendly to the Empire. In 867, the same Patriarch Photius announced to his fellow Eastern Patriarchs that the Russians who had attacked Constantinople not too long before had accepted a bishop. Seven years later, we hear of an “Archbishop of the Rus’,” although we do not know where his episcopal seat was located.

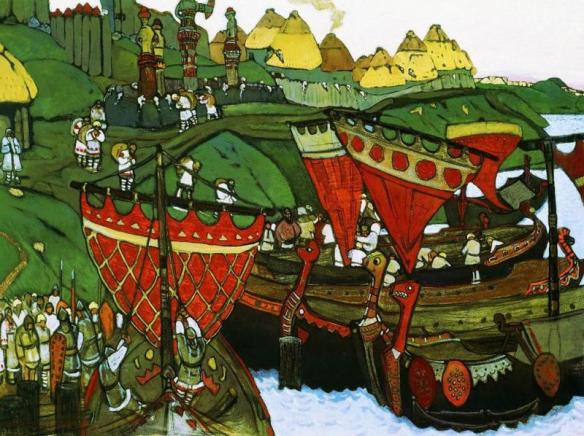

The first recognizable Kievan Rus’ state was formed to protect the by now profitable Rus’ trade with Byzantium on the famed “way from the Varangians to the Greeks.” Viking traders (the Varangians of Russian and Byzantine sources) unified and fortified the upper and middle Dnieper waterway in the ninth century, replacing the faltering Turkic Khazars, who had earlier guaranteed safety on the trade routes across the steppe. The precious goods of the northern forest lands (furs, slaves, honey) were brought to the stronghold of Kiev on the middle Dnieper River and then transported by flotilla each spring down the river, over the portages, and by boat along the coast of the Black Sea to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. There they were traded for Mediterranean luxury articles (wine, jewelery, fine fabrics), which were brought back to the land of Rus’ and beyond, to Scandinavia, and sometimes to the East. The tenth-century Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus describes the early Rus’ trading expeditions to Byzantium in detail in his ruler’s handbook, de administrando imperio.

It was to guarantee their trade rights in the Byzantine capital that Rus’ again attacked Constantinople. The attack came in the year 907, and this time the Rus’ came from the recently created Kiev Rus’ state; the Rus’ force was led by Prince Oleg. The Russian chronicle description of the campaign is overlain with much legendary detail (boats sailing over land on wheels, attempted poisonings discovered, etc.), and Byzantine sources make no reference to this attack. But the attack must have actually occurred. The text of the treaty that the Byzantines signed in 911 (formalizing the earlier Russo-Byzantine agreement from 907) preserved in Slavic translation in the Russian Primary Chronicle has all the hallmarks of a genuine Byzantine diplomatic document signed under Rus’ military pressure. The treaty stipulates the rights of Rus’ merchants to trade in Constantinople tax free and to enjoy the benefits of a merchant headquarters in the St. Mamas quarter on the Bosphorus close to the city. It also spells out details on how to settle legal disputes between Rus’ people and “Christians.” The treaty also guarantees the rights of Rus’ who wish to serve in the Byzantine armed forces, and, indeed, a Byzantine source records 700 Rus’ serving in the Byzantine navy in 911, offering some confirmation of the genuineness of the treaty from the Greek side.

In June 941 Igor, Oleg’s successor, led a new attack on the Byzantine Empire, probably for the same reason: trade rights. The Rus’ army approached imperial territory by sea, attacked and pillaged along the Black Sea Coast of Asia Minor, and advanced to the Asiatic shores of the Bosphorus, sacking Chrysopolis located across from Constantinople itself. The leading Byzantine general, John Curcuas, headed back from the Empire’s eastern frontier to lead the successful attack on the Rus’ forces outside Constantinople. As the Rus’ were preparing to withdraw, the Byzantine navy attacked their ships in the Bosphorus with Greek fire, a medieval form of napalm shot through tubes that could set ships afire.

The Rus’ fighters who could escape did; those who had not burned to death were killed by the Byzantine military. Still, the lure of Constantinople and its trade continued unabated among the Rus’, and in just over two years, the Rus’ prince Igor once again assembled a mighty force to attack Constantinople. This time the Byzantines offered gifts and terms to the Russians, including essentially reinstating the earlier treaty of 911 negotiated by Oleg, suggesting once again that trade rights were the paramount reason for Igor’s campaigns. Ostensibly at the demand of his retinue, Igor accepted the Byzantine proposals, and turned back from the river Danube, not even entering Byzantine territory. He took home with him a new treaty with Byzantium, albeit with somewhat less favorable terms.

Along with the much desired trade with Byzantium came cultural influences, most notably the beginnings of Christianity in Kievan Rus’. Already in 944, some of the Rus’ officials swore to the new treaty with the Byzantines in a Church of St Elias in the city of Kiev, although others followed the pagan Viking rites for ratifying an agreement. The progress of Christianity in Kievan Rus’, probably brought back by Rus’ military men who returned home after serving in the Byzantine military, led to the baptism of Princess Olga, widow of the murdered Prince Igor and regent for their young son Sviatoslav, heir apparent to the Kievan throne. This baptism took place between 954 and 956, and probably in Constantinople. The Russian chronicle tradition has Olga being baptized, with Emperor Constantine VII acting as her godfather. In honor of the emperor’s wife, Olga assumed Helen as her baptismal name (also recalling the name of the first Christian empress of the Roman Empire).

Although the Byzantine sources are silent about Olga’s baptism, they are quite effusive in describing her official reception at the imperial palace, where she was richly feted, along with her very significant entourage. She returned home with appropriately rich gifts, an honorary Byzantine court title, and, one suspects, a renewed trade treaty.

By the time young Sviatoslav came of age, he had already rejected the Christianity of his mother (because the members of his military retinue would laugh at him, says the Primary Chronicle); like his father, he was destined to be a military man. Sviatoslav created a large military force, which he used to conquer several neighboring tribes; he even defeated the Khazars and took their city of Sarkel (Bela Vezha). Having proven his military prowess, Sviatoslav was commissioned by the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus Phocas to put down an impending attack from Bulgaria for a large fee. Thus, in 968, Sviatoslav appeared on the Danube and quickly overwhelmed the Bulgarians. He was called back to Kiev, however, by a dangerous siege of his capital city by the Pechenegs (Patzinaks), perhaps acting in concert with the Byzantines, who now wanted him out of the Balkans. The Pechenegs had replaced the Khazars as the dominant power on the steppes of southern Rus’. After relieving the Pecheneg siege of the city, Sviatoslav announced that he did not want to remain in Kiev, but would prefer rather to settle in the Bulgarian city of Pereiaslavets on the Danube, which he now described as the center of his realm. And, indeed, after burying his mother Olga, Sviatoslav returned to his Balkan conquests and captured and deposed the Bulgarian tsar Boris II. He also now apparently laid claim to all the European holdings of the Byzantines!

The new Byzantine emperor, the general John Tzimiskes, who had succeeded the assassinated Emperor Nicephorus, had (temporarily) freed himself from military commitments on the Empire’s eastern frontier and moved to destroy the Rus’ Frankenstein his predecessor had created in the Balkans. He tried to win over the Bulgarian people, who were supporting Sviatoslav against the Byzantines, but also mounted a massive military offensive. In April 971 Tzimiskes’ army retook the Bulgarian capital of Preslav, capturing the dethroned Bulgarian king and setting him up again as the ruler. Moving swiftly toward Dristra (Silistria, Dorostolon), the fortified city on the Danube where Sviatoslav had holed up, the Byzantine forces put the fortress under siege, aided by the appearance in the Danube of Byzantine ships capable of launching the dreaded Greek fire. Sviatoslav’s Rus’ troops fought heroically, but lack of food eventually forced them to come to terms. Sviatoslav was forced to swear to withdraw from the Balkans and never to return, not to attack the Byzantine city of Cherson in the Crimea, and to render military aid to the Byzantines when asked. In return, he and the remnant of his forces were given supplies and allowed to return to the land of Rus’. Under somewhat suspicious circumstances, however, the Rus’ force was waylaid on the way home by Pecheneg nomads as it forded rapids on the Dnieper River, and Sviatoslav was killed, his skull being made into a drinking cup for a Pecheneg chief.