Highest development of Stone Age warfare, with some variations. Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica provides an excellent study area for the development of warfare on a different path than in the old world. The lack of draft and pack animals, wheels, metallurgy, and ships in quantity and quality all led to developments different from those in Europe.

The Olmecs (1200-400 B. C. E.) first used warfare to expand trade and access to resources. Fighters from the Olmec city of San Lorenzo utilized obsidian-edged weapons, handto- hand elite combat, and small, elite forces numbering in the tens to hundreds to control local trade routes from the Veracruz region. La Venta assumed power from 900 to 400 B. C. E. and introduced the sling, clay projectiles, and yuccacotton armor to gain superiority. Tortillas were also used to feed the hundreds of troops deployed in enemy territory. By 400, trophy heads, stone knives, obsidian-tip spears, spear throwers, wood shields, upper-torso armor, and hide helmets were common for elites and, to a lesser extent, for supporting commoner forces.

Fortifications also became common, especially in the lowland Mayan area where captive taking and elite warfare dominated. In the Zapotec region, Monte Alban developed as a heavily fortified city that controlled a regional kingdom through its defensive location and warfare based on thrusting spears and hand-to-hand combat. Skull racks indicate probable religious-based warfare centered on captives and sacrifice. By 100 C. E., Monte Alban was challenged by the huge city-state of Teotihuacan in the Mexico City area. From 100 to 700 Teotihuacan, which numbered perhaps 100,000 people, spread its influence over trading partners partly by emphasizing spear throwers, shields, and stone axes and knives. The Teotihuacanos utilized military orders of eagles, jaguars, and so on, special housing, regular production of weapons, and nodal control of trade centers over 1,500 miles distant. Astronomy and religion seem to have played a large role in how and why war was carried out at the end of Teotihuacan hegemony.

In 378, the Teotihuacanos brought projectile warfare into the Mayan region and tipped the balance of power in favor of large Mayan cities like Tikal, with rulers like Smoking- Frog. These lowland Maya developed religious- and astronomy- based warfare among elites that became known as “star wars.” The kin-city competitions for resources, natural and supernatural, dominated classic Mayan warfare from 378 to 900, when warfare may have helped to collapse classical Maya civilization.

In most cases, these early and classic period civilizations in Mesoamerica focused on elite warfare and weaponry, with religion and trade as key motivating factors. Most “armies” numbered less than a thousand soldiers, were supported logistically by commoners, and sought out captives as a way of removing rival dynasties and usurping power. It was as important to take religious items of power as it was to take a city. By the early post-Classic period, between 700 and 900, warfare began to change significantly.

At places like Xochicalca, Cacaxtla, or Bonampak, people like the Olmeca-Xicallanca increased warrior numbers, used backpacks in long-distance attacks on cities like Teotihuacan, and involved commoners in guerrilla activities. After the collapse of classic Mesoamerican civilizations, the Toltecs rose to power in central Mexico between 900 and 1200, and their ascendance marked the rise of territorial warfare, combined arms, and highly militaristic society. They would have a great influence on the later Aztecs (Mexica).

Tollan and its Toltec capital of Tula in central Mexico used large armies in the tens of thousands, concentrated projectile fire of spear throwers, obsidian blades on wood clubs and swords, siege warfare with firing platforms, and watercraft, when necessary. One leader, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, may have invaded Yucatan territory after 1100 and spread full-scale warfare into the region from the site of Chichén Itza. Itza fought with Coba for control of Yucatan for several centuries. The Itza eventually prevailed in a conflict that saw the fortifications, attrition, and logistics of the Coba defeated by Itza Mexican military might. However, both sides had exhausted their resources, and soon a series of smaller kingdoms returned control of the peninsula to Maya polities by 1350.

In the post-Classic period, waves of Chichemecan invaders from the north, such as the Toltecs and Aztecs, combined their nomadic, commoner-based, bow-and-arrow warfare with the elite, trained, central Mexico warfare traditions. The Maya region struggled to keep up but was about to be overrun by the time of Spanish invasions in 1519.

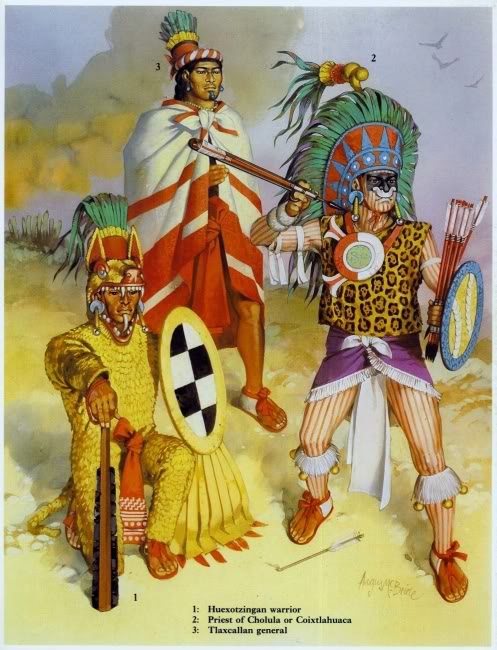

The Aztecs established their capital Tenochtitlan on an island in Lake Texcoco and used this combined approach to establish a huge tributary empire by war between 1300 and 1521. They eventually controlled much of Mesoamerica, notable exceptions being the west Mexican Tarascan kingdom, the Tlaxcallan kingdom, and the Maya lowlands.

Tlacaelel was most responsible for the building of the Aztec Empire. He ruled as a warrior-priest, supporting relative after relative as emperor, for most of the fifteenth century. When he died at 96, he left a legacy of military training schools for elites and commoners, arms production, the ability to field huge armies of 100,000 or more for long campaigns, a religious-military system that promoted and supported war and captive taking, and the largest, most powerful empire in the pre-Columbian Americas.

The Aztecs, like the Inca, often defeated enemies by logistics and numbers, not by military superiority. Time and again, the Aztecs were actually defeated on the battlefield by Tarascan metal weaponry and fortifications, Tlaxcallan volley bow and arrow fire, or even in hand-to-hand combat. Still, the Aztecs usually prevailed in the end.

References and further reading: Hassig, Ross. War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Sahagun, Bernardino de. General History of the Things of New Spain. Trans. Arthur J. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. 13 vols. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950-1982. Tsouras, Peter. Warlords of the Ancient Americas: Central America. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1996.