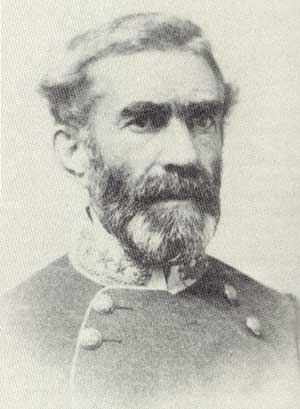

A personal favorite of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Braxton Bragg was a fine organizer and a strategist of real ability during the Civil War. However, his lack of nerve under stress, coupled with a garrulous, combative personality, limited his effectiveness for field command and cost the Confederacy several key victories.

The twenty-seventh of February 1862 was an active day for Confederate strategists. While General Lovell waxed so confident (and, as it turned out, so incorrect) about Union intentions, David J. Houston, a farmer from Natural Bridge, Virginia, penned a note to Jefferson Davis. Houston had five sons in the army and worried that Confederate forces were “defending too much territory.” “Napoleon divided and conquered in detail,” he said, and suggested concentrating forces at several towns in Virginia. He also advised defending only a few important sites along the Confederate coast, “stationing all forces on or near railroads for rapid movements.” Davis sent the letter, the first of a number that he received during the war that in some respects forecast Confederate strategy, on to Lee. At the time, big things were brewing strategically in the South. Fort Henry had fallen to Grant and Foote on February 6, and Roanoke Island fell to General Burnside two days later; Donelson surrendered on the sixteenth. These defeats deflated Rebel spirits; “the Cause” needed reviving. As Houston’s missive made its way through the mails, the Confederacy prepared its riposte.

On February 22, 1862, Davis delivered an official inaugural address to the Confederate Congress in which he admitted to the error of trying to defend the entirety of the Confederate frontier and attributed the recent disasters at Donelson and Roanoke to this unfortunate decision. But, he insisted, “strenuous efforts have been made to throw forward reinforcements to the Armies at the positions threatened.” He made a number of observations: that Maryland would join the Confederacy if given free rein, which was likely true, and that the Union would soon “sink under the immense load of debt they have incurred,” which was less likely for the North than it was for the South. He also turned Clausewitzian in his expression of how much the South desired its independence, revealing the depth of his dedication to “the Cause”- something shared by the bulk of the South’s white population (and some of its black)-and an awareness of the bitter sacrifice the war would require: “But we knew the value of the object for which we struggled, and understood the nature of the war in which we were engaged. Nothing could be so bad as failure, and any sacrifice would be cheap as the price of success in such a contest.” For the Confederacy, the real sacrificing had begun. Lincoln had taken the gloves off, and the South was discovering that it was fighting above its weight.

Before Houston sent his note to Davis, advice came from the Western Theater from the hand of Major General Braxton Bragg. A former U. S. Army officer, Bragg had a reputation for quarrelsomeness in the prewar army. Later, he would demonstrate great administrative skills that enabled him to weld from a disorganized mass an effective organization that became the Army of Tennessee. He would also suffer from divisional commanders who proved habitually disobedient, a tendency exacerbated by Bragg’s indecision and a natural disputatiousness that led him to fight with everyone around him. But this was later. At this moment Bragg offered Secretary of War Judah Benjamin the reasons for Confederate failure, as well as a new strategy: “Our means and resources are too much scattered,” he wrote. “The protection of persons and property, as such, should be abandoned, and all our means applied to the Government and the cause. Important strategic points only should be held. All means not necessary to secure these should be concentrated for a heavy blow upon the enemy where we can best assail him. Kentucky is now that point.” Bragg recommended abandoning all their posts on the Gulf of Mexico except Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans, as well as all of Texas and Florida, “and our means there made available for other service.” “A small loss of property would result from their occupation by the enemy,” he continued, “but our military strength would not be lessened thereby, whilst the enemy would be weakened by dispersion. We could then beat him in detail, instead of the reverse. The same remark applies to our Atlantic seaboard. In Missouri the same rule can be applied to a great extent. Deploring the misfortunes of that gallant people, I can but think their relief must reach them through Kentucky.” He also stressed the need for unity transcending local interests. His later correspondence with Beauregard reinforced these views. “We should cease our policy [strategy] of protecting persons and property, by which we are being defeated in detail.”

This was perhaps the most cogent strategic plan offered by any Confederate leader during the course of the war. Bragg had identified the Confederacy’s key weakness-that it lacked the means to defend its far-flung regions-and recognized that defending the vital core of the Confederacy, the area east of the Mississippi and north of Florida, was what mattered. Losing the rest would do little to injure the Confederacy’s power. He wanted to mass Confederate military strength in its center and then move to offensive warfare. There was also a limitation to Bragg’s thinking: it applied generally to the West, particularly Kentucky and Tennessee.