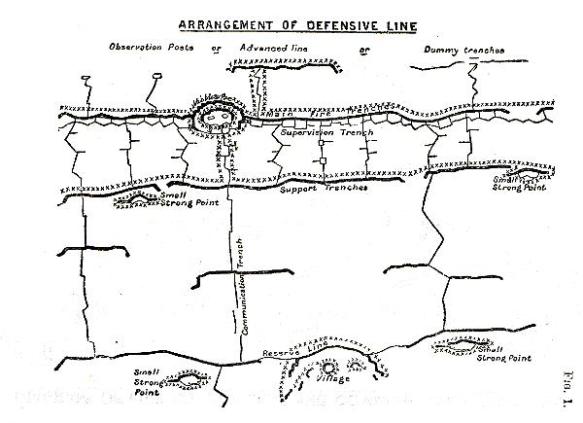

Trench construction diagram from a 1914 British infantry manual

The year 1915 was a formative experience, one in which the lines of development which would be followed through into the battles of 1918 were put in place. Although the front was static, the thinking of the armies was not. The western front was an intensely competitive environment, where the innovation of one side was emulated, improved upon or negated by the other. Ironically, it was this very cycle of action and reaction, designed to break the deadlock, which confirmed it. But at its conclusion the armies of both sides were equipped, organised and fought in very different ways from those of 1914.

Immediately Haig’s prescription created fresh problems more than it resolved old ones. ‘In this siege war in the open field, it is not enough to open a breach‘, General Marie-Emile Fayolle confided to his diary on 1 June 1915, ’it is necessary that it is about 20 km wide, at the least, or one cannot fan out to right and left. To do that needs a whole army and there has to be another one ready to carry on.‘ But in 1915 neither the British nor the French had enough guns or shells, let alone heavy artillery, to be able to attack on a broad front. By concentrating on a narrow front, the available guns might reach into the depth of the enemy positions, but the attackers were then liable to enfilade from the flanks. Furthermore, the concentration of artillery and its preliminary, and increasingly extended, bombardment forfeited the element of surprise. Most attacks succeeded in breaking into the enemy’s position. The problem was that of reinforcing and exploiting success, and that in turn depended on immediate support from troops to the rear.

The static nature of the front line enabled the armies to lay down light railways to transport shells and other supplies to the front lines. But horses were still basic to their transport systems Britain sent more oats and hay (by weight) to France than ammunition.

Haig’s belief that offensives should be fought on broad, not narrow, fronts, and be preceded by long, not short, bombardments was born at the battle of Neuve Chapelle, the first of the British spring offensives in 1915. But Neuve Chapelle also highlighted the intractabilities of communication, and the consequent difficulty of knowing when and where to commit reserves. On 10 March 1915, at 8.05 a.m., after a short (thirty-five-minute) bombardment, the infantry launched a surprise attack. In the centre the German front line was taken in ten minutes and the village of Neuve Chapelle itself was in British hands before 9 a.m. Reports of these initial gains reached Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, the corps commander, within an hour. Douglas Haig, by now commanding one of the two armies into which the expanding British Expeditionary Force had been divided, ordered a cavalry brigade to ready itself and harboured hopes of his whole army beginning a general advance. But the artillery had been less effective on the left, and there the attack came under fire from its flank. The British did not take the German front line until 11.20, and therefore the lead units on the right. were in danger of being isolated, and were told to wait for further instructions. Communications went up the command chain from battalion to brigade, from brigade to division, and at last reached corps headquarters five miles back. At 1.30 p.m. Rawlinson issued instructions for a fresh advance at 2.30 p.m., but the supporting units were not ready, and at 3 p.m. he set the attack for 3.30. Orders had to be transmitted back down the line of command, acquiring more detail as they went. Those passing between division and battalion had taken between one and two hours throughout the day. At 3.30 the artillery opened fire; and hit its own infantry. By 4 p.m. both the forward brigades were attacking but without artillery support or effective lateral communications between themselves. The light was failing, surprise had been lost and enemy defence was hardening.

Neuve Chapelle confirmed that the biggest constraint on the conduct of land war was the lack of real-time communications. Infantry in fixed positions could bury telephone wire from the front line back to their supporting artillery and higher commands. However, as they went forward to attack they lost contact. They could unroll wire as they advanced but it was frequently cut by shellfire. Wirelesses were still too heavy to be man-portable; they were the preserve of higher commands and navies. Pigeons could do the job if the wind and weather conditions were right, but they were reluctant to fly on the damp, still days which tended to prevail on the western front. Drizzle or mist prevented other forms of observation – the firing of rockets or flares, or the waving of flags in order to indicate progress. The Germans used dogs to carry messages, but the usual method of communicating progress or of calling for support was human. Runners had to renegotiate the open ground they had just crossed in the attack. Even if they survived, their information was old by the time it was in the hands of those for whom it was destined.

Accordingly, generals could do little to intervene in the immediate decision-making of a battle. The creation of mass armies and the necessity of dispersion in the face of modern firepower meant that the battlefield had extended, while at the same time apparently emptying. The supreme commander could not take in the situation with a sweep of his field glasses from some vantage point. Now his tasks were more managerial than inspirational. He found ‘himself further back in a house with a spacious office, where telegraphs, telephones and signals apparatus are to hand’, Schlieffen had written before the war. ‘There, in a comfortable chair before a wide table, the modern Alexander has before him the entire battlefield on a map.’ Linear, positional warfare exacerbated this trend, forcing the commander to place himself behind his troops. The German response to the problem was to delegate command forward, confining instructions to general directives and avoiding detailed orders. British officers were used to smaller forces and more hands-on command in colonial campaigns. Moreover, mobile warfare in 1914 had briefly kept alive the notions of a more heroic age. In the course of the entire war seventy-one German and fifty-five French generals lost their lives, and it is reasonable to assume that most of those who did so in battle were killed in the opening months. British generals proved almost foolhardy by comparison: between 1914 and 1918 seventy-eight were killed in action, an enormous total given that the army did not really expand until the front had stabilised and startling confirmation of the assertion of Cyril Falls, himself a staff officer, that British generals were in fact ‘too eager to get away from their desks’. What they found hard to accept was that vital decisions were being taken at lower levels of authority. At the beginning of the war the corps of, say, 30,000 men was the key operational command. But the corps was squeezed from the top by the creation of army and army group commands, and from the bottom by the division of about 12,000 men. The latter took the corps’ place as the lowest all-arms operational formation, and acquired an identity which was more lasting and cohesive than that of the corps. The task of heroic and inspiring leadership passed even lower down the command chain to junior officers, the commanders of companies, platoons and even sections.

In 1915 Entente strategy had an ad hoc quality. The western front represented an irreducible minimum. That was particularly the case for France, although it did not prevent the French from pursuing other options in the eastern Mediterranean, at Gallipoli and Salonika. The British seemed still to have a measure of choice. Some Liberals, particularly Reginald McKenna, Lloyd George’s successor as chancellor of the exchequer, cleaved to the notion that Britain’s primary contribution should be naval and economic: it should be the arsenal and financier of the Entente. McKenna argued that British manpower would be best used if it sustained home production and thus ensured the flow of exports that would fund Britain’s international credit and its ability to buy arms overseas and supply them to its allies. But McKenna’s hopes were ill founded. When Kitchener was appointed secretary of state for war in August 1914, he set about the creation of a mass army for deployment on the continent of Europe. By July 1915 the War Office was talking of seventy divisions, a tenfold increase on the army’s size a year before. Although originally raised through voluntary enlistment, such an army could be kept up to strength only by conscription. Many of the men McKenna wanted on the factory floor were needed by the army, and the produce of those that remained went to equip that army, not to support Britain’s overseas balance of trade.

Kitchener himself suggested Britain should delay its major effort until 1917, by which time the Continental armies would have fought each other to a standstill and the British could take the credit for ending the war. The New Armies’ training and equipment was a lengthy process, but they could not realistically be held back for that long. In the short term the obvious reserves of manpower lay in Russia, but if the Russians were to do the hard fighting in 1915-16 they – not Kitchener’s New Armies – should get the fruits of Britain’s war industries. The retreat of the Russian armies in the summer of 1915 and the defeat at Gallipoli confirmed that Kitchener’s notion of choice was as illusory as McKenna’s. The Russians had now even greater need of British munitions, but they were also desperate for direct military support from the west to draw off the Germans. Furthermore, in France Joffre faced hardening political opposition. By sacking the most republican of his army commanders, General Maurice Sarrail, for perfectly proper military reasons, he provided a focus for the left’s criticisms of the army’s independence of political control. The government of René Viviani came under threat, and with it the national cohesion embodied in the union sacrée. Britain feared the upshot of a domestic political crisis in France. Their worst nightmares embraced a government under Joseph Caillaux and the possibility that he might seek an accommodation with Germany. Kitchener reversed his views of Britain’s role on the western front: on 19 August 1915 he told Haig that ‘we must act with all our energy, and do our utmost to help the French, even though by so doing, we suffer very heavy losses indeed’. British strategy was tied to that of its allies, and of France especially.