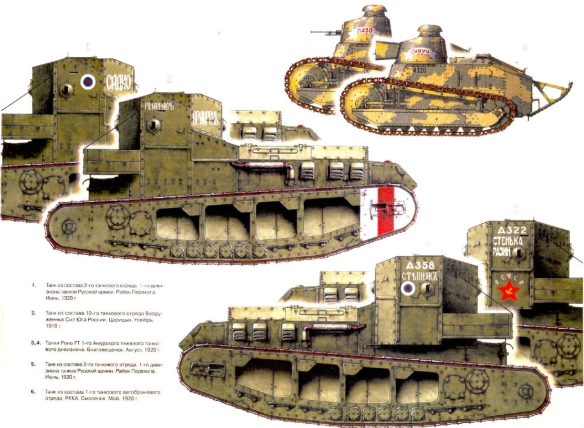

The Soviet Union produced a large number of tank designs in the period between the two world wars. Early Russian experiments with AFVs in World War I had been limited to armored cars, such as the Austin Putilov. Based on a British chassis, it had entered service early in World War I. Lacking the industrial base of the other major military powers, the Russians concentrated in the postwar period on light tanks of simple design. Their first tanks were a few British and French models captured by the Bolshevik forces (known as the Reds) from their opponents (the Whites) during the Russian Civil War.

It was logical that Britain and France would take the lead in new technology; after all, they were mounting the bulk of the attacks as they sought to drive the Germans from territory seized in Belgium and northeastern France. The Germans were for the most part content to remain on the defensive, hoping to win the war in the East while wearing down their antagonists in the West.

The armored car was not the answer to the impasse; its wheels made it impractical for navigating earth torn up by artillery fire and usually muddy from the high water table in northeastern France and the destruction of drainage systems by the shelling. A new weapon was required, one that could maneuver over the torn-up battlefield, break through masses of barbed-wire entanglements, and span trenches. The solution lay in an internal combustion engine- powered vehicle, but one that was tracked and armored as opposed to wheeled. Tracking was essential not only to allow navigation in battlefield conditions but also to distribute the heavy weight of the vehicle over a greater area.

In 1915 both Britain and France began development of armored and tracked fighting vehicles. Neither coordinated with the other, and the result was a profusion of different types and no clear doctrine governing their employment. Other nations-Italy, Russia, Japan, Sweden, Czechoslovakia, Spain, Poland, and the United States-produced tanks either during or immediately after World War I and during the 1920s, but only Great Britain, France, and Germany manufactured tanks that actually saw combat service in World War I, and Germany produced only a few.

The Royal Navy took the lead. This was the consequence of the Admiralty having been assigned the task of defending Britain from German air attack, which in turn led to the stationing of British naval air squadrons at Dunkerque (Dunkirk) in northeastern France to attack German Zeppelin sheds and airplane bases in Belgium. These air bases required perimeter defense, and the new armored car squadrons provided it. To prevent these vehicles from moving about, the Germans cut gaps in the roads, and First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill immediately called “for means of bridging those gaps.” Throughout his long public life, Churchill remained immensely interested in military gadgetry and innovation. He was, in fact, quite proud of his role in the development of the tank.

As the British increased both the numbers and efficiency of their armored cars in late 1914, trench lines on both sides reached the English Channel and it was no longer possible to outflank enemy positions. Now it would be necessary to go through these lines.

Even before the war, Churchill had opened discussions with retired Rear Admiral Reginald Bacon, who had been director of Naval Ordnance in 1909 but had retired to become general manager of the Coventry Ordnance Works. Shortly after the beginning of the war Bacon discussed with Churchill a plan for a 15-inch howitzer to be transported by road. Bacon believed that even the largest fortresses could not withstand bombardment from such powerful siege artillery. This was borne out a few weeks later in the German destruction of Belgian forts, most notably those at Liege. Churchill then entered into more talks with Bacon and proposed to the War Office that it contract with him to build 10 such guns. Secretary of State for War Field Marshal Horatio Kitchener supported the idea, and the guns were completed in time to take part in the aforementioned Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915. Each of these great howitzers, along with its firing platform and ammunition, was moved in sections by eight enormous field tractors.

When in October 1914 Bacon showed Churchill photographs of the tractors, Churchill sensed the possibilities and asked him whether the tractors could be made to span trenches and carry guns and infantry, or whether another such vehicle could be constructed to perform these tasks. Bacon then produced a design for a “caterpillar tractor” able to cross over a trench by means of a portable bridge, which it would lay beforehand and then retrieve afterward. Early in November Churchill ordered Bacon to manufacture an experimental model. This showed sufficient promise that in February 1915 Churchill ordered Bacon to manufacture 30 of them.

The War Office tested the first of Bacon’s machines in May 1915 but rejected it because it proved unable to meet certain conditions, including climbing a 4-foot bank or going through 3 feet of water, a feat not achieved by any tank to the end of the war. Churchill’s order for 30 of the machines had already been canceled by the time of the first test because a better design had appeared, advanced by Lieutenant Colonel of Engineers Ernest D. Swinton.

At the beginning of the war Swinton was serving as deputy director of railway transport, but Kitchener made him a semiofficial war correspondent for British forces in France following public opposition to a ban on war correspondents in the war zone imposed by the French army commander, General Joseph Joffre. Swinton wrote his articles under the pen name “Eyewitness.”

In traveling the front Swinton realized the deadlock imposed by trench warfare and above all by the machine gun. He envisioned “a self-propelled climbing block-house or rifle bullet-proof cupola.” But on the evening of 19 October 1914, while driving by car to Calais, Swinton recalled a report on the California Holt tractor. Swinton believed the new war machine would have to have such a caterpillar track. Although Swinton claimed to have originated the idea, others were already experimenting independently with caterpillar tracks at the beginning of 1915.

Whether he originated the idea or not, Swinton certainly was the key figure in British tank development. Completing his assignment as a war correspondent, he returned to Britain to serve as assistant secretary for the Committee of Imperial Defence, known since the beginning of the war as the Dardanelles Committee of the Cabinet. Later in October Swinton met with the secretary of the committee, Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Hankey, and suggested to him the conversion into fighting machines of Holt gasoline engine-powered caterpillar tractors used for repositioning artillery. The process for converting the idea of a fighting “landship” into a practical machine had begun. It would be a case of plowshares being beaten into swords.

Well before the war, in Britain and especially in the United States, steam-powered tracked vehicles had been developed for agricultural purposes. As such tractors would have to move over plowed terrain, there was also considerable experimentation with both suspension and track linkage systems. Yet there was little enthusiasm for such machines for military use in the years before World War I. When a representative of the Holt Company of Britain tried to interest the German Army in a military tractor, for example, he was told, “No importance for military purposes.”

In December Hankey produced a paper supporting the idea of a military vehicle based on the farm tractor, which he then circulated among members of the War Cabinet. Churchill, who was already at work on the same concept with Bacon, supported it in a lengthy memorandum to Prime Minister Herbert H. Asquith on 5 January 1915, in which he urged the manufacture of

a number of steam tractors with small armoured shelters, in which men and machine guns could be placed, which would be bullet proof. Used at night they would not be affected by artillery fire to any extent. The caterpillar system would enable trenches to be crossed quite easily, and the weight of the machine would destroy all wire entanglements. Forty or fifty of these engines prepared secretly and brought into position at nightfall could advance quite certainly into the enemy’s trenches, smashing away all the obstructions and sweeping the trenches with their machine-gun fire and with grenades thrown out of the top. They would then make so many points d’appui for the British supporting infantry to rush forward and rally on them.

Churchill proposed that a committee of “engineering officers and other experts” meet at the War Office to examine the possibility. Never patient where a new military idea was concerned, Churchill opined that something should have been done in this regard months before. He urged speed as well as the manufacture of different patterns. “The worst that can happen,” he wrote, “is that a comparatively small sum of money is wasted.”

Prime Minister Asquith agreed and urged Kitchener, who supported the plan, to proceed. But the effort then bogged down in the War Department bureaucracy. Churchill continued to give some attention to the plan, and in late January he directed that experiments be undertaken with steam rollers that might be used to smash in enemy trench systems. This scheme proved unsuccessful. Then on 17 February 1915, Churchill met with some officers of the armored car squadrons and the conversation turned to discussion of the creation of “land battleships.”

Three days later, on 20 February, Churchill ordered the formation of the Landships Committee at the Admiralty. By late March it had come up with two possible designs, one moving on large wheels and the other by tracks. On 26 March, on his own responsibility and at a cost of about £70,000, Churchill ordered manufacture of 18 landships: six wheeled and 12 tracked. A variety of designs now came forward, each registering improvements.

The failure of the Allied Powers to achieve a breakthrough on the Western Front produced more support for the armored fighting vehicle concept, and that June Swinton drafted a memorandum for a means of overcoming the German machine guns. He also provided specific details of capabilities for such “armored machine-gun destroyers.” Swinton called for the weapon to weigh about 8 tons, have a crew of 10 men, and mount two machine guns and a quick-firing 6-pounder gun capable of firing high-explosive shells. It was to have a 20-mile radius of action, 10mm thick armor, a top speed of not less than 4 mph on flat ground, a capability of traveling in reverse, the ability to carry out a sharp turn at top speed, a trench-spanning capability of 8 feet, and the ability to climb a 5-foot earthen parapet.

Arthur Balfour, who followed Churchill at the Admiralty on the latter’s resignation in May over the failure of the Dardanelles/Gallipoli campaign, was sympathetic to the project, as was Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George. Under pressure from Field Marshal Sir John French, the BEF commander in France who demanded that the War Office research Swinton’s ideas, the Landships Committee at the Admiralty became a joint army-navy group with the War Office director of fortifications as its chair.

Balfour approved construction of one experimental machine. The contract went to William Foster and Co., a manufacturer of agricultural machinery in Lincoln. William Tritton, managing director of Foster, had already designed a 105-hp trench-spanning machine as well as models of other armored vehicles and howitzer tractors. The prototype for the British government contract became known as “Little Willie.” Designed by Tritton and Major William Wilson, who was assigned as a special adviser for the project, it ran for the first time on 3 December 1915.

Little Willie, the first tracked, potentially armored vehicle, bears a remarkable resemblance to its tank successors, or at least to APCs, into the twenty-first century. It weighed some 40,300 pounds, had a 105-hp gasoline engine, a road speed of 1.8 mph, and 6mm steel plating. Its set of trailing wheels, designed to provide stability in steering, proved unsuccessful, however. Although Little Willie was never armed, the top of the hull sported a ring with the intention that it would mount a mock-up turret. Little Willie went on to serve as a training vehicle for tank drivers.

As Little Willie was making its appearance, Foster was completing work on a battlefield version. Because the chief requirements for the vehicle were that it be able to cross open ground as well as wide trenches, Tritton and Wilson came up with a lozenge-shaped design with a long, upward-sloping, tall hull and all-around tracks on either side that carried over its top. These maximized the vehicle’s trenchcrossing ability. Because a turret would have made the machine too high, its designers mounted the guns in sponsons, one on either side of the hull. As it turned out, this was not a satisfactory arrangement. The resulting machine was first known as “Centipede,” then “Big Willie,” and finally “Mother.”

Mother first moved under its own power on 12 January 1916. Thirty-two feet long and weighing some 69,400 pounds, it debuted on 29 January 1916 in Hatfield Park, within a mile of Lincoln Cathedral and under extremely tight security. A second demonstration on 2 February took place in front of British military and political leaders, including cabinet members. In Swinton’s words,

it was a striking scene when the signal was given and a species of gigantic cubist steel slug slid out of its lair and proceeded to rear its grey hulk over the bright-yellow clay of the enemy parapet, before the assemblage of Cabinet Ministers and highly placed sailors and soldiers collected under the trees.

Although Mother met the expectations placed on it, even crossing a 9-foot trench with ease, Kitchener was unimpressed. He held to his already stated belief that the new weapon was little more than “a pretty mechanical toy.” But Kitchener was in the minority. Most of those in attendance were quite persuaded as to the new weapon’s potential. The enthusiasts included Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir William Robertson, Prime Minister Balfour, and Lloyd George. Balfour was even given a ride. Churchill was certainly correct when he wrote in his memoirs that Mother was “the parent and in principle the prototype of all the heavy tanks that fought in the Great War.”

Another trial was held on 8 February before King George V. Three days later the BEF in France requested the new weapon be sent there, and shortly thereafter the government ordered 100 units (later increased to 150), with production to be overseen by a new committee.

Unfortunately, the perceived need to rush the new weapon into production meant that design flaws remained largely uncorrected. For one thing Mother was woefully underpowered. The 28-ton vehicle was propelled by a 105-hp Daimler engine, the only one available. This translated into only 3.7 horsepower per 1 ton of weight. Half of Mother’s eight-man crew was engaged simply in driving it: one as commander, another to change the main gear, and two “gearsmen,” or “brakemen,” who controlled the tracks; the remaining four men manned two 6-pounders (57mm/2.25-inch) and two machine guns. The new machine was also insufficiently armored. Its 10mm protection could not keep out German armor-piercing bullets at close range, and a direct hit by a high-explosive artillery round would most likely be fatal.

The production model, known as the Mark I, was almost identical to Mother. It weighed some 62,700 pounds and had a top speed of only 3.7 mph-over rough ground only half that-and it had a range of some 23 miles. Its principal parts were a simple, steel box-type armored hull, two continuous caterpillar tracks, a 105-hp Daimler gasoline engine, and armament of cannon and/or machine guns. A two-wheeled trailing unit assisted with steering, but this was soon discarded as ineffective over rough ground and vulnerable to enemy fire. The clutch-and-brake method was then employed on the tracks but required four crewmen. And though it could span a 10-foot trench, the Mark I was only lightly armored in the mistaken belief that this would be sufficient to protect against rifle and machinegun fire. Armor varied in thickness from 6mm to 12mm.

Turning the tanks was a time-consuming, difficult process. One British participant in the Battle of Cambrai recalled that rounds

were striking the sides of the tank. Each of our six pounders required a gun layer and a gun loader, and while these four men blazed away, the rest of the perspiring crew kept the tank zig-zagging to upset the enemy’s aim. . . . It required four of the crew to work the levers, and they took their orders by signals. First of all the tank had to stop. A knock on the right side would attract the attention of the right gearsmen. The driver would hold out a clenched fist, which was the signal to put the track into neutral. The gearsmen would repeat the signal to show it was done. The officer, who controlled two brake levers, would pull on the right one, which held the right track. The driver would accelerate and the tank would slew round slowly on the stationary right track while the left track went into motion. As soon as the tank had turned sufficiently, the procedure was reversed.

In between pulls on his brakes the rank commander fired the machine gun.

The Mark I came in two types. Half of them mounted two 6- pounder/.40-caliber naval guns in sponsons, or half-turrets, on the sides that provided a considerable arc of fire, with four machine guns; these were known as the “male” version. The “female” version mounted six machine guns and was intended to operate primarily against opposing infantry.

The name “tank,” by which these armored fighting vehicles became universally known, was intended to disguise the contents of the large crates containing the vehicles when they were shipped to France. The curious would draw the conclusion that the crates held water tanks. The French made no such effort at name deception; they called their new weapon the char (chariot).

The Mark I was the mainstay of tank fighting in 1916 and early 1917, but it had notable defects. The stabilizer tail proved worthless; its fuel tanks were in a vulnerable position; the exhaust outlet on the top emitted telltale sparks and flame; and there was no way for a “ditched” tank to retrieve itself. Some of these deficiencies were addressed in the Marks II and III. These tanks appeared alongside the Mark I in early 1917.

The Foster Company manufactured 50 Mark II and 50 Mark III tanks. Produced in the same male and female versions and almost identical to the Mark I, they differed only in details. The Mark II, for example, had wider track plates fitted at each sixth link that distributed its weight over a larger area, preventing it from becoming as easily bogged down. The Mark III had improved armor. Superseded by the Mark IV, many Mark IIs and IIIs were converted into supply and specialist vehicles.