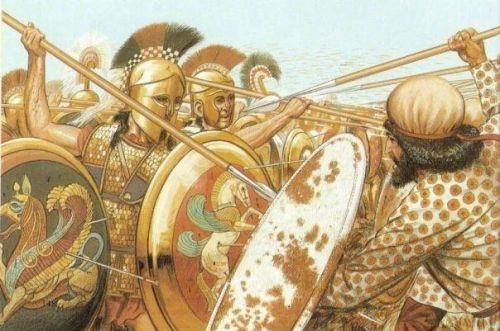

Herodotus refers to Greek hoplites as `men of bronze’ in a reference to the armour that they wore and this is a perfectly apt description. The equipment carried by a Greek hoplite was designed for only one thing-straight-up, hand-to-hand, combat. To fight as a hoplite only two pieces of equipment were necessary-the shield and the spear-everything else was an optional extra.

The hoplite shield (aspis) was a weighty piece of defensive armament specifically designed for the rigours of close combat and the Greek formation (the phalanx). The aspis was made from a solid wooden core turned on a lathe to create a shallow bowl-like shape which allowed its weight to be supported by the left shoulder. The left arm was inserted through a central armband (porpax), which the playwright Euripides states was custom made to suit the arm of the bearer, while the left hand grasped a cord (antilabe) that ran around the inner rim of the shield. Occasionally faced with bronze (or having only its offset rim covered in bronze), and nearly 1m in diameter, the Greek shield weighed in the vicinity of 7kg. The hoplite’s primary offensive weapon was a long thrusting spear (doru) which was approximately 2.5m long with a leaf-shaped iron head at the tip and a large bronze spike, known as a sauroter or `lizard killer’, on the back. The total weight of this weapon was around 1.5kg.

On his body a hoplite could wear some form of armour (thorax). This could have been one of two types: a bronze plate cuirass approximately 1.5mm thick, or a linen composite armour (linothorax) made from gluing several layers of linen and/or hide together to make a material not unlike modern Kevlar. The bronze cuirass of the fifth century BC was beaten into a stylized musculature representing a human torso. This served a number of purposes. It was a demonstration of wealth due to the cost of having such armour made; it made the wearer look more impressive and frightening to an enemy; and it reduced the amount of flat surfaces on the armour. These curved surfaces on the front of the cuirass deflected incoming weapon strikes by increasing the respective angle of impact-thus requiring a greater amount of energy delivered in the strike to pierce it. The total weight of either bronze or linen armour was around 5.6kg.

On his head a hoplite may have worn a helmet (kranos). The most common style of helmet worn in Greece in the fifth century BC was the Corinthian helmet-an all encompassing, solid bronze helmet which protected the whole head from throat to crown, and which could be adorned with an additional crest made of stiffened horse hair. The total weight of the helmet and crest was around 2.4kg. On his legs a hoplite may have worn bronze greaves (knemis). Shaped to fit onto the lower leg, and held in place via the elasticity of the metal, greaves were designed to protect the lower legs from missile impacts and weighed around 1kg. The sword (xiphos/machaira) was the hoplite’s secondary weapon in close combat. Depending upon the style employed, the sword weighed around 2kg. All up, when a tunic, footwear and padding under the armour are taken into consideration, a full panoply worn by the Greek hoplite weighed around 21kg. Due to the extent of the armour worn and the formation adopted, when a hoplite positioned himself for battle, a person of average size (170cm tall) wearing a full panoply had only 395cm2 (or 5.5 per cent) of their body exposed.

The average weight of the head of the doru was 153g, while the average weight of the sauroter, the large bronze spike on the rear of the shaft, was 329g. Due to the difference in weight between the head and the butt-spike, the hoplite spear had a point of balance around 90cm from the rear end of the weapon. The doru was wielded by tucking it up into the armpit in what is known as the `underarm position’; much in the same way a medieval knight carried his lance during a joust. Due to the weapon’s rearward point of balance, a doru held in the underarm position projected forward of the man wielding it by about 1.6m.

If a contingent of Greek hoplites adopted a close-order formation, in which each man occupied a space 45-50cm in size both front-to-back and side-to-side, the shields of the men in each rank would overlap to create a strong, interlocking `shield wall’. The shield wall was primarily a static defensive formation, although it was also used offensively by experienced troops who could advance slowly to maintain the integrity of the line. In a narrow pass like that at Thermopylae, a contingent of Greeks (such as the famous 300 Spartans) could have deployed a close-order phalanx thirty-five men across and about eight ranks deep. In such a formation, the spears held by the second rank also projected well forward of the formation and could easily reach an attacking enemy. Due to the space occupied by the men in each rank of a close-order formation, their spears were separated by only 45-50cm. Additionally, as the spears held by the second rank also projected forward of the line, a formation of thirty-five men across would have presented two serried rows of seventy levelled spears-all of which could have engaged the enemy. This made the Greek hoplite individually, and the Greek close-order phalanx as a whole, very well suited to hand-to-hand combat and almost impervious to missile fire.

Unfortunately for the Persians, their entire system of warfare was based upon a much more open style of fighting and they were armed accordingly. There are numerous passages in the ancient narrative histories which describe how the weapons and armour of the Greeks were superior to that of the Persians in close combat-in particular the doru which is always described as longer than the Persian spear. Herodotus does not provide a lot of detail on the armament of the Persian troops that fought at Marathon in 490 BC, but he does give a detailed description of the troops that accompanied the second Persian invasion of Greece a decade later. The best armed troops within the invasion force at that time were the 10,000 strong Persian `Immortals’, closely followed by the Median contingent. The Immortals were armed with a short spear (paltron), a bow with reed arrows and a dagger. For protection they wore a cloth cap, scale armour and carried a shield made from woven wicker which would have been completely inadequate in terms of protection against a strong spear thrust.

However, the majority of the Persian army that fought in 480 BC were not as well equipped as the Immortals and the Medes. All of the contingents within the Persian army were armed in their particular native styles-most of which were not suited for hand-to-hand combat. Herodotus tells us that the contingent from Ethiopia, for example, wore only animal skins, and were armed with a bow and stone tipped arrows, spears tipped with antelope horns and wooden clubs. In another example, Herodotus describes the Libyan contingent as wearing only a leather loincloth and being armed with a sharpened stick that had been hardened in a fire. Other contingents in the Persian army were either equipped with bows and arrows or with melee weapons such as swords, clubs, axes and maces which would have had a much shorter reach than the lengthy Greek spear. Troops such as this, while well suited to a more mobile, hit-and-run style of warfare or an open melee form of combat, were completely outclassed when fighting against men who were almost fully encased in plate bronze, and who were arranged in a close-order combative formation like the Greek hoplite. Even before the first blow was struck the Persians at Marathon (and later at Thermopylae and Plataea) were at a disadvantage. This was due to the Greek hoplite, and his equipment, being designed for hand-to-hand combat while the Persian way of war was based around skirmishing, hit-and-run tactics, and using missile weapons to hit your enemy from a distance while relying on weight of numbers and cavalry. This accounts for why the Persians were so lightly armoured in comparison to the Greeks as recorded by Herodotus and for the references in the ancient texts which outline the superiority of Greek weapons and armour.

The different fighting style employed by the Persians also explains the different configuration of the Persian paltron to the Greek doru. The paltron was slightly shorter than the Greek spear-about 2m in length-just as many of the ancient texts describe. Importantly, the paltron had only a small butt on the rear end of its shaft and this gave the weapon a central point of balance. This was because the paltron was designed to be both a missile and a thrusting weapon and was generally held in the overhead position in preparation to throw it or to stab downwards with it (as is shown on Persian cylinder seals). A further indication that the paltron was designed primarily to be a missile weapon is that it had a much thinner shaft-only 19mm in diameter. This created a weapon that was lighter and easier to throw, but was much more susceptible to breakage than the more robust Greek spear, which had a thicker shaft of 25mm in diameter, and which was specifically designed for the rigours of hand-to-hand combat. Due to the different ways in which the two weapons were held, a Greek hoplite had a reach of more than 2.2m with his weapon when he extended his arm forward into the attack. The Persians on the other hand, holding a centrally balanced weapon above their head and stabbing forwards and downwards with it, had a reach of only 1.4m. This means that in most engagements, the Persians would not have been able to reach the Greeks with their weapons, let alone overcome their superior armament, while the front of the Persian line was vulnerable to attacks delivered by the first two ranks of the Greek phalanx. This disparity in both armament and fighting style accounts for the large differences in the number of casualties sustained by the Persians compared to those suffered by the Greeks at battles like Marathon, Thermopylae and Plataea.