World War II was the most destructive enterprise in human history. It is sobering to consider that more resources, mate- rial, and human lives (approximately 50 million dead) were expended on the war than on any other human activity. Indeed, this conflict was so all-encompassing that very few “side” wars took place simultaneously, the 1939–1940 Finnish-Soviet War (the Winter War) being one of the few exceptions.

The debate over the origins of World War I had become something of a cottage industry among historians in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet the question of origins rarely arises over World War II, except on the narrow issue of whether U. S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had advance knowledge of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Whatever their grievances (certainly minor in comparison to the misery they inflicted on their victims), Germany and Japan are still considered the aggressors of World War II.

World War II is historically unique in that it represents if not necessarily a “crusade” of good against evil at least a struggle against almost pure evil by less evil forces. More than half a century after the end of this war, no mainstream or serious historians defend any significant aspect of Nazi Germany. Perhaps more surprisingly, there are also few if any such historians who would do likewise for militaristic Japan. In practically all previous conflicts, historians have found sufficient blame to give all belligerents a share. For example, no prominent historian takes seriously the Versailles provision that Germany was somehow completely responsible for the out- break of World War I. German Führer Adolf Hitler and his followers have thus retained mythic status as personifications of pure evil, something not seen since the Wars of Religion of seventeenth-century Europe.

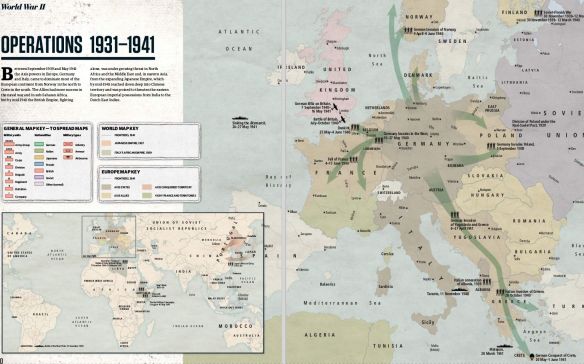

The starting date of World War II, however, can be disputed. Some scholars have gone as far back as the Japanese seizure of Manchuria in 1931. Others date its outbreak to the opening of the full-scale Sino-Japanese War in 1937. But these were conflicts between two Asian powers, hardly global war.

The more traditional and more widely accepted date for the start of World War II is 1 September 1939, with the quick but not quite blitzkrieg (lightning) German invasion of Poland. This action brought France and Great Britain into the conflict two days later in accordance with their guarantees to Poland. (The Soviet Union’s invasion of eastern Poland on 17 September provoked no similar reaction.)

The Germans learned from their Polish Campaign and mounted a true blitzkrieg offensive against the Low Countries and France, commencing on 10 May 1940. In this blitzkrieg warfare, the tactical airpower of the German air force (the Luftwaffe) knocked out command and communications posts as integrated armor division pincers drove deeply into enemy territory, bypassing opposition strong points. When all went well, the pincers encircled the slow-moving enemy. Contrary to legend, the armored forces were simply the spearheads; the bulk of the German army was composed of foot soldiers and horses. Further, the French army and the British Expeditionary Force combined had more and usually better tanks than the Germans, and they were not too seriously inferior in the air. The sluggish Allies were simply out- maneuvered, losing France in six weeks, much to the astonishment of the so-called experts. France remains the only major industrial democracy ever to be conquered— and, also uniquely, after a single campaign. It was also the only more or less motorized nation to suffer such a fate; many French refugees fled the rapidly advancing Germans in their private cars. The Germans found that the French Routes Nationales (National Routes), designed to enable French forces to reach the frontiers, could also be used in the opposite direction by an invader. The Germans themselves relearned this military truth on their autobahns in 1945.

Germany suffered its first defeat of the war when its air offensive against Great Britain, the world’s first great air campaign, was thwarted in the Battle of Britain. The margin of victory was small, for there was little to choose between the Hurricane and Spitfire fighters of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Luftwaffe’s Bf-109 or between the contenders’ pilots. The main advantages of the RAF in this battle were radar and the geographic fact that its pilots and their warplanes were shot down over Britain itself; German pilots and aircraft in a similar predicament were out of action for the duration, and they also had farther to fly from their bases. But Great Britain’s greatest advantage throughout this stage of the war was its prime minister, Winston L. S. Churchill, who gave stirring voice and substance to the Allied defiance of Hitler.

Nonetheless, by the spring of 1941, Nazi Germany had conquered or dominated all of the European continent, with the exception of Switzerland, Sweden, and Vatican City. Greece, which had held off and beaten back an inept Italian offensive, finally capitulated to the German Balkan blitzkrieg in spring 1941. Nazi Germany then turned on its erstwhile ally, the Soviet Union, on 22 June 1941, in Operation BARBAROSSA , the great- est military campaign of all time, in order to fulfill Hitler’s enduring vision of crushing “Judeo-Bolshevism.” (How far Hitler’s ambitions of conquest ranged beyond the Soviet east is still disputed by historians.) If he had any introspective moments then, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin must have wished that he still possessed the legions of first-rate officers he had shot or slowly destroyed in the gulag in the wake of his bloody purge of the military in 1937. Stalin’s own inept generalship played a major role in the early Soviet defeats, and German forces drove almost to within sight of the Kremlin’s towers in December 1941 before being beaten back.

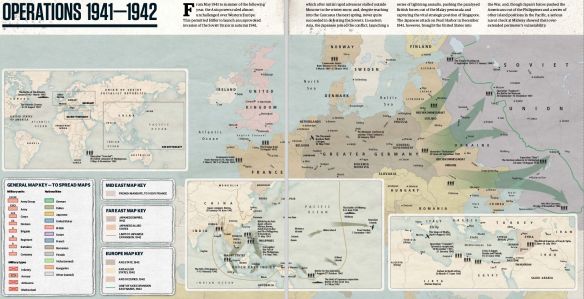

Early that same month, war erupted in the Pacific, and the conflict then became truly a world war, with Japan’s coordinated combined attacks on the U. S. naval base at Pearl Harbor and on British, Dutch, and American imperial possessions. With the Soviet Union holding out precariously and the United States now a belligerent, the Axis had lost the war, even though few recognized that fact at the time. America’s “great debate” as to whether and to what extent to aid Britain was silenced in a national outpouring of collective wrath against an enemy, in a manner that would not be seen again until 11 September 2001.

But Pearl Harbor was bad enough, with 2,280 Americans dead, four battleships sunk, and the remaining four battle- ships damaged. Much worse was to follow. As with the Ger- mans in France, more-professional Japanese forces surprised and outfought their opponents by land, sea, and air. Almost before they knew it, British and Dutch forces in Asia, superior in numbers alone, had been routed in one of the most successful combined-arms campaigns in history. (The French had already yielded control of their colony of Indochina, whose rice and raw materials were flowing to Japan while the Japanese military had the use of its naval and air bases until the end of the war.) The course of the Malayan-Singapore Campaign was typical. British land forces could scarcely even delay the Japanese army, Japanese fighters cleared the skies of British aircraft, and Japanese naval bombers flying from land bases quickly sank the new battleship Prince of Wales and the elderly battle cruiser Repulse. This disaster made it obvious that the aircraft carrier was the capital ship of the day. Singapore, the linchpin of imperial European power in the Orient, surrendered ignominiously on 16 February 1942.

The British hardly made a better fight of it in Burma before having to evacuate that colony. Only the Americans managed to delay the Japanese seriously, holding out on the Bataan Peninsula and then at the Corregidor fortifications until May. The end of imperialism, at least in Asia, can be dated to the capitulation of Singapore, as Asians witnessed other Asians with superior technology and professionalism completely defeat Europeans and Americans.

And yet, on Pearl Harbor’s very “day of infamy,” Japan actually lost the war. Its forces missed the American aircraft carriers there, as well as the oil tank farms and the machine shop complex. On that day, the Japanese killed many U. S. personnel, and they destroyed mostly obsolete aircraft and sank a handful of elderly battleships. But above all, they outraged Americans, who determined to avenge the attack so that Japan would receive no mercy in the relentless land, sea, and air war that the United States was now to wage against it. More significantly, American industrial and manpower resources vastly surpassed those Japan could bring to bear in a protracted conflict.

And yet—oddly, perhaps, in view of its own ruthless warfare and occupation—Japan was the only major belligerent to hold limited aims in World War II. Japanese leaders basically wanted the Western colonial powers out of the Pacific, to be replaced, of course, by their own Greater East Asia Co- prosperity Sphere (a euphemism for “Asia for the Japanese”). No unconditional surrender demands ever issued from Tokyo. To Japan’s own people, of course, the war was presented as a struggle to the death against the arrogant Anglo- Saxon imperialists.

Three days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Hitler decided to declare war on the United States, a blunder fully as deadly as his invasion of the Soviet Union and even less explicable. But the Nazi dictator, on the basis of his customary “insights,” had dismissed the American soldier as worthless, and he considered U. S. industrial power vastly overrated. His decision meant the United States could not focus exclusively on Japan.

The tide would not begin to turn until the drawn-out naval-air clash in the Coral Sea (May 1942), the first naval battle in which neither side’s surface ships ever came within sight of the opponent. The following month, the U. S. Navy avenged Pearl Harbor in the Battle of Midway, sinking no fewer than four Japanese carriers, again without the surface ships involved ever sighting each other. The loss of hundreds of superbly trained, combat-experienced naval aviators and their highly trained maintenance crews was as great a blow to Japan as the actual sinking of its invaluable carriers. The Americans could make up their own losses far more easily than the Japanese.

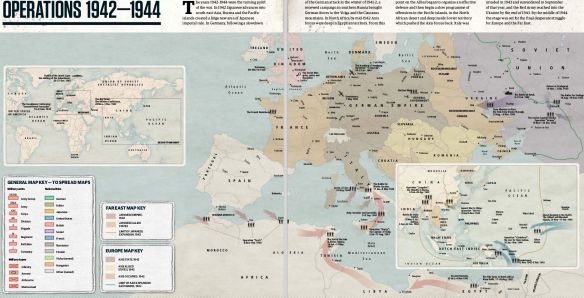

Although considered a sideshow by the Soviets, the North African Campaign was of the utmost strategic importance, and until mid-1943, it was the only continental land campaign that the Western Allies were strong enough to mount. Had North Africa, including Egypt, fallen to the Axis powers (as almost occurred several times), the Suez Canal could not have been held, and German forces could have gone through the Middle East, mobilizing Arab nationalism, threatening the area’s vast oil fields, and even menacing the embattled Soviet Union itself. Not until the British commander in North Africa, General Bernard Montgomery, amassed a massive superiority in armor was German General Erwin Rommel defeated at El Alamein in October 1942 and slowly pushed back toward Tunisia. U. S. and British landings to the rear of Rommel’s forces, in Algeria and Morocco, were successful, but the raw American troops received a bloody nose at Kasserine Pass. The vastly outnumbered North African Axis forces did not capitulate until May 1943. Four months earlier, the German Sixth Army had surrendered at Stalingrad, marking the resurgence of the Soviet armies. One should, nonetheless, remember that the distance between Casablanca, Morocco, and Cape Bon, Tunisia, is much the same as that from Brest-Litovsk to Stalingrad, and more Axis troops surrendered at “Tunisgrad” than at Stalingrad. (One major difference was that almost all Axis prisoners of the Western Allies survived their imprisonment, whereas fewer than one in ten of those taken at Stalingrad returned.)

By this time, U. S. production was supplying not only American military needs but also those of most of the Allies—on a scale, moreover, that was simply lavish by comparison to all other armed forces (except possibly that of the Canadians). Everything from the canned-meat product Spam to Sherman tanks and from aluminum ingots to finished aircraft crossed the oceans to the British Isles, the Soviet Union, the Free French, the Nationalist Chinese, the Fighting Poles, and others. (To this day, Soviets refer to any multidrive truck as a studeborkii, or Studebaker, a result of the tens of thousands of such vehicles shipped to the Soviet Union.) Moreover, quantity was not produced at the cost of quality. Although some the Allies might have had reservations in regard to Spam, the army trucks, the boots, the small arms, and the uniforms provided by the United States were unsurpassed. (British soldiers noted with some envy that American enlisted men wore the same type of uniform material as did British officers.) The very ships that transported the bulk of this war material—the famous, mass-produced Liberty ships (“rolled out by the mile, chopped off by the yard”)— could still be found on the world’s oceanic trade routes decades after they were originally scheduled to be scrapped.

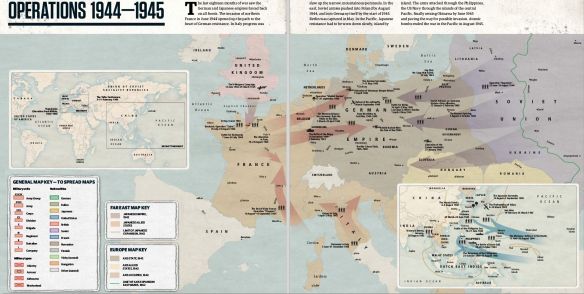

After the North African Campaign ended in 1943, the Allies drove the Axis forces from Sicily, and then, in September 1943, they began the interminable Italian Campaign. It is perhaps indicative of the frustrating nature of the war in Italy that the lethargic Allies allowed the campaign to begin with the escape of most Axis forces from Sicily to the Italian peninsula. The Germans were still better at this sort of thing. Winston Churchill to the contrary, Italy was no “soft underbelly”; the Germans conducted well-organized retreats from one mountainous fortified line to the next. The Italian Campaign was occasionally justified for tying down many German troops, but the truth is that it tied down far more Allied forces—British, Americans, Free French, Free Poles, Brazilians, Canadians, Indians, and British and French African colonials among them. German forces in Italy ultimately surrendered in late April 1945, only about a week before Ger- many itself capitulated.

The military forces of World War II’s belligerents, as might be expected in so historically widespread a conflict, varied wildly. The French army in 1939, considered by “experts” the world’s best, was actually a slow-moving mass that was often supplied with very good equipment and was led by aged commanders who had learned the lessons of World War I. No other such powerful army was so completely defeated in so short a period of time. The French air force and navy likewise had some excellent equipment as well as more progressive commanders than the army, but France fell before they could have any great impact on the course of battle.

It is generally agreed that the German army was superb— so superb, in fact, that some authorities would venture that the Germans traditionally have had “a genius for war.” (Then again, it was hardly a sign of genius to provoke the United States into entering World War I or to invade the Soviet Union in World War II while the British Empire still fought on, before declaring war on the United States six months later.) Obviously, Germany’s greatest and traditional military failing has been the denigration of the fighting ability of its opponents. But on the ground, at the operational and tactical levels, the combination of realistic training, strict discipline, and flexible command made the German army probably World War II’s most formidable foe. One need only look at a map of Europe from 1939 to 1945 and calculate Germany’s enemies compared to its own resources. The Luftwaffe had superbly trained pilots, although their quality fell off drastically as the war turned against their nation. German fighters were easily the equal of any in the world, but surprisingly, given that Hitler’s earlier ambitions seemingly demanded a “Ural bomber,” the Luftwaffe never put a heavy, four-engine bomber into production. Germany led the world in aerodynamics, putting into squadron service the world’s first jet fighter (the Me-262), with swept wings, and even a jet reconnaissance bomber (although German jet engines lagged somewhat behind those of the British). The Luftwaffe also fielded a rocket-powered interceptor, but this craft was as great a menace to its own pilots as to the enemy.

The German navy boasted some outstanding surface vessels, such as the battleship Bismarck, but Hitler found the sea alien, and he largely neglected Germany’s surface fleet. Sub- marines were an entirely different matter. U-boat wolf packs decimated Allied North Atlantic shipping, and the Battle of the Atlantic was the only campaign the eupeptic Churchill claimed cost him sleep. German U-boats ravaged the Atlantic coast of the United States, even ranging into Chesapeake Bay in the first months of 1942 to take advantage of inexcusable American naval unpreparedness. As in World War I, convoy was the answer to the German U-boat, a lesson that had to be learned the hard way in both conflicts.

The British army on the whole put in a mediocre performance in World War II. As with the French, although to a lesser degree, the British feared a repetition of the slaughter experienced on the World War I Western Front, and except for the elite units, they rarely showed much dash or initiative. Montgomery, the war’s most famous British general, consistently refused to advance until he had great superiority in men and material over his enemy. The British Expeditionary Force fought well and hard in France in 1940 but moved sluggishly thereafter. By far the worst performance of the British army occurred in Malaya-Singapore in the opening months of the war.

For all of their commando tradition, moreover, the British undertook few guerrilla actions in any of their lost colonies. Churchill himself was moved to wonder why the sons of the men who had fought so well in World War I on the Somme, despite heavy losses, suffered so badly by comparison to the Americans still holding out on Bataan. As late as 1943, the Japanese easily repulsed a sluggish British offensive in the Burma Arakan.

This situation changed drastically when General William Slim took command of the beaten, depressed Anglo-Indian forces in Burma. His was the only sizable Allied force not to outnumber the Japanese, yet he inflicted the worst land defeat in its history on Japan and destroyed the Japanese forces in Burma. Unlike so many Allied generals, Slim led from the front in the worst climate of any battle front. He managed to switch his army’s composition from jungle fighters to armored cavalry. Slim’s only tangible advantage over his enemy was his absolute control of the air, and with this, he conducted the greatest air supply operation of the war. Although the modest Slim, from a lower-middle-class background, achieved the highest rank in the British army and then became one of Australia’s most successful governor-generals, he is almost forgotten today. Yet, considering his accomplishments with limited resources and in different conditions, William Slim should be considered the finest ground commander of World War II.

The Royal Navy suffered from a preponderance of battleship admirals at the opening of the war, most notably Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, who was convinced that “well-handled” capital ships could fight off aerial attacks. He was proved emphatically and fatally wrong when Japanese torpedo- bombers rather swiftly dispatched his Prince of Wales and Repulse on the third day after the opening of war in the Pacific. The Royal Navy was also handicapped by the fact that not until 1937 did it win control of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) from the RAF, which had little use for naval aviation and had starved the FAA of funds and attention through the years between the world wars. Although the Royal Navy’s carriers were fine ships and their armored flight decks gave them a protection that the U. S. Navy envied, albeit at the cost of smaller aircraft capacity, Fleet Air Arm aircraft were so obsolete that the service had to turn to U. S. models. Even so, the FAA made history on 11 November 1940 when its obsolete Fairy Swordfish torpedo- bombers sank three Italian battleships in Taranto harbor, a feat that the Japanese observed carefully but the Americans did not. British battleships and carriers kept the vital lifeline through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal open through the darkest days of the war, and together with the Americans and Canadians, they defeated the perilous German submarine menace in the North Atlantic. Significant surface actions of the Royal Navy included the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck in May 1941 by an armada of British battleships, cruisers, carriers, and warplanes and the December 1943 destruction of the pocket battleship Scharnhorst by the modern battleship Duke of York.

The Soviet army almost received its deathblow in the first months of the German invasion. Caught off balance and shorn by Stalin’s maniacal purges of its best commanders (whose successors were the dictator’s obedient creatures), the Soviet army suffered heavier losses than any other army in history. Yet, spurred by the bestiality of the German war of enslavement and racial extermination and by Stalin’s new-found pragmatism, the Red Army was able to spring back and, at enormous cost at the hands of the more professional Germans, fight its way to Berlin.

The Red Air Force developed into one of the most effective tactical air powers of the war. (The Soviets constructed very few heavy bombers.) The Shturmovik was certainly one of the best ground-attack aircraft of the time. The Red Navy, by contrast, apparently did little to affect the course of the war; its main triumph may have been in early 1945 when its sub- marines sank several large German passenger ships crammed with refugees from the east in the frigid Baltic, the worst maritime disasters in history.

The United States emerged from World War II as the only nation since the time of the Romans to be a dominant power on both land and sea, not to mention in the air. In 1945, the U. S. Air Force and Navy could have defeated any combination of enemies, and only the Soviet army could have seri- ously challenged the Americans on land. In 1939, the U. S. Army was about the size of that of Romania; by 1945, it had grown to some 12 million men and women.

World War II in the Pacific was the great epic of the U. S. Navy. From the ruin of Pearl Harbor, that service fought its way across the vast reaches of the Pacific Ocean to Tokyo Bay. Eventually, it had the satisfaction of watching the Japanese surrender on board a U. S. Navy battleship in that harbor. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, it was obvious that the air- craft carrier was the ideal capital ship for this war, and the United States virtually mass-produced such warships in the Essex-class. The U. S. Navy had much to learn from its enemy, as demonstrated in the Battle of Savo Island, where Japanese cruisers sank three U. S. and one Australian cruiser in the worst seagoing defeat in U. S. naval history. By the end of the war, almost all of Japan’s battleships and carriers had been sunk, most by naval airpower. U. S. Navy submarines succeeded where the German navy had failed in two world wars, as absolutely unrestricted submarine warfare strangled the Japanese home islands, causing near starvation. Equally impressive, the U. S. Navy in the Pacific originated the long- range sea-train, providing American sailors with practically all their needs while they fought thousands of miles from the nearest continental American supply base.

The U. S. Marine Corps was a unique military force. Alone among the marine units of the belligerents, it had its own air and armor arms under its own tactical control. The U. S. Marines were the spearhead that stormed the Japanese-held islands of the Pacific, and the dramatic photograph of a small group of Marines raising the American flag over the bitterly contested island of Iwo Jima became an icon of the war for Americans.

The Japanese army was long on courage but shorter on individual initiative. It was a near medieval force, its men often led in wild banzai charges by sword-flourishing officers against machine-gun emplacements. The entire nation of Nippon was effectively mobilized against the looming Americans under the mindless slogan “Our spirit against their steel.” But the history of the Japanese army will be stained for the foreseeable future by the bestial atrocities it practiced against Allied troops and civilians alike; untold numbers of Chinese civilians, for example, were slaughtered during Japanese military campaigns in China. Only two-thirds of Allied troops unfortunate enough to fall into Japanese hands survived to the end of the war. Yet the Japanese army was probably the best light infantry force of the war, and it was certainly the only World War II army that, on numerous occasions, genuinely fulfilled that most hackneyed order “Fight on to the last man!”

The Imperial Japanese Navy and the air arms of the army and navy were superb in the early stages of the Pacific war. Both had extensive combat experience in the Chinese war as well as modern equipment. Japanese admirals were the best in their class between 1941 and 1942, and Japanese air and naval forces, along with the Japanese army itself, quickly wound up European colonial pretensions. Only the vast mobilized resources of the United States could turn the tide against Japan. And except for their complete loss of air control, only in Burma were the Japanese outfought on something like equal terms.

The aftermath of World War II proved considerably different from that of World War I, with its prevailing spirit of disillusionment. Amazingly, all of World War II’s belligerents, winners and losers alike, could soon look back and realize that the destruction of the murderous, archaic, racialist Axis regimes had genuinely cleared the way to a better world. All enjoyed peace and the absence of major war. Even for the Soviets, the postwar decades were infinitely better than the prewar years, although much of this measure of good fortune might be attributed simply to the death of Josef Stalin. Except for Great Britain, the British Commonwealth nations and even more so the United States emerged from the war far stronger than when they entered it after enduring a decade of the Great Depression. By the 1950s, both war-shattered Western Europe and Japan were well on their way to becoming major competitors of the United States. The uniquely sagacious and foresighted Western Allied military occupations of Germany, Japan, and Austria in many ways laid the foundations for the postwar prosperity of these former enemy nations. (For the most part, similar good fortune bypassed the less developed nations.) Within a few years, former belligerents on both sides could agree that, despite its appalling casualties and destruction, World War II had been if not perhaps “the Good War” at least something in the nature of a worthwhile war.

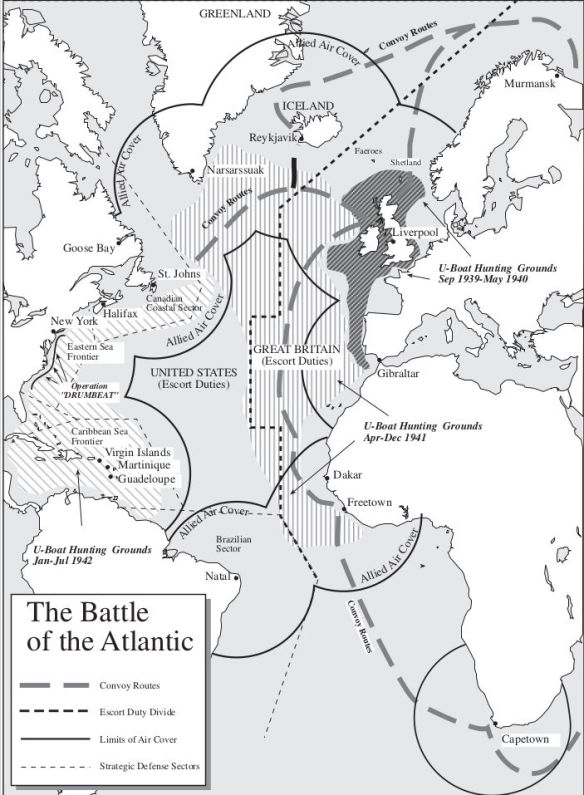

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest campaign of World War II. In it, the German navy tried to sever the Allied sea lines of communication along which supplies necessary to fight the war were sent to Great Britain. To carry out the battle, the Germans employed a few surface raiders, but principally they used U-boats.

At the beginning of the war, the German navy possessed not the 300 U-boats deemed necessary by Kommodore (commodore) Karl Dönitz (he was promoted to rear admiral in October 1939), but 57 boats, of which only 27 were of types that could reach the Atlantic from their home bases. Although an extensive building program was immediately begun, only in the second half of 1941 did U-boat numbers begin to rise.

On the Allied side, British navy leaders were at first confident that their ASDIC (for Allied Submarine Detection Investigating Committee) location device would enable their escort vessels to defend the supply convoys against the sub- merged attackers, so that shipping losses might be limited until the building of new merchant ships by Britain, Canada, and the United States might settle the balance. However, Dönitz planned to concentrate groups of U-boats (called “wolf packs” by the Allies) against the convoys and to jointly attack them on the surface at night. It took time, however, before the battles of the convoys really began. The Battle of the Atlantic became a running match between numbers of German U-boats and the development of their weapons against the Allied merchant ships, their sea and air escorts with improving detection equipment), and new weapons.

The Battle of the Atlantic may be subdivided into eight phases. During the first of these, from September 1939 to June 1940, a small number of U-boats, seldom more than 10 at a time, made individual cruises west of the British Isles and into the Bay of Biscay to intercept Allied merchant ships. Generally, these operated independently because the convoy system, which the British Admiralty had planned before the war, was slow to take shape. Thus the U-boats found targets, attacking at first according to prize rules by identifying the ship and providing for the safety of its crew. However, when Britain armed its merchant ships, increasingly the German submarines struck without warning. Dönitz’s plan to counter the convoy with group or “pack” operations of U-boats— also developed and tested before the war—was put on trial in October and November 1939 and in February 1940. The results confirmed the possibility of vectoring a group of U- boats to a convoy by radio signals from whichever U-boat first sighted the convoy. However, at this time, the insufficient numbers of U-boats available and frequent torpedo failures prevented real successes.

The German conquest of Norway and western France provided the U-boats with new bases much closer to the main operational area off the Western Approaches and brought about a second phase from July 1940 to May 1941. In this phase, the U-boats, operated in groups or wolf packs, were directed by radio signals from the shore against the convoys, in which was now concentrated most of the maritime traffic to and from Great Britain. Even if the number of U-boats in the operational area still did not rise to more than 10 at a time, a peak of efficacy was attained in terms of the relationship between tonnage sunk and U-boat days at sea. This was made possible partly by the weakness of the convoy escort groups because the Royal Navy held back destroyers to guard against an expected German invasion of Britain. In addition, British merchant shipping losses were greatly augmented during this phase by the operations of German surface warships in the north and central Atlantic; by armed merchant raiders in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans; by the attacks of German long-range bombers against the Western Approaches; and by heavy German air attacks against British harbors. The Ger- mans were also aided by Italian submarines based at Bordeaux and sent into the Atlantic, the numbers of which in early 1941 actually surpassed the number of German U-boats.

In late 1940 and spring 1941, when the danger of an inva- sion of the British Isles had receded, London released destroyers for antisubmarine operations and redeployed Coastal Command aircraft to support the convoys off the Western Approaches. Thus, in the third phase of the Battle of the Atlantic, from May to December 1941, the U-boats were forced to operate at greater distances from shore. Long lines of U-boats patrolled across the convoy routes in an effort to intercept supply ships. This in turn forced the British in June to begin escorting their convoys along the whole route from Newfoundland to the Western Approaches and—when the U-boats began to cruise off West Africa—the route from Freetown to Gibraltar and the United Kingdom as well.

In March 1941, the Allies captured cipher materials from a German patrol vessel. Then, on 7 May 1941, the Royal Navy succeeded in capturing the German Arctic meteorological vessel München and seizing her Enigma machine intact. Settings secured from this encoding machine enabled the Royal Navy to read June U-boat radio traffic practically currently. On 9 May during a convoy battle, the British destroyer Bull- dog captured the German submarine U-110 and secured the settings for the high-grade officer-only German naval signals. The capture on 28 June of a second German weather ship, Lauenburg, enabled British decryption operations at Bletchley Park (BP) to read July German home-waters radio traffic currently. This led to interception of German supply ships in the Atlantic and cessation of German surface ship operations in the Atlantic. Beginning in August 1941, BP operatives could decrypt signals between the commander of U-boats and his U-boats at sea. The Allies were thus able to reroute convoys and save perhaps 1.5 million gross tons of shipping. During this third phase, the U. S. Atlantic Fleet was first involved in the battle.

The entry of the United States into the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor ushered in the fourth phase of the battle, presenting the U-boats with a second golden opportunity from January to July 1942. Attacking unescorted individual ships off the U. S. East Coast, in the Gulf of Mexico, and in the Caribbean, German U-boats sank greater tonnages than during any other period of the war.

But sightings and sinkings off the U. S. East Coast dropped off sharply after the introduction of the interlocking convoy system there, and Dönitz found operations by individual U- boats in such distant waters uneconomical. Thus, in July 1942, he switched the U-boats back to the North Atlantic con- voy route. This began the fifth phase, which lasted until May 1943. Now came the decisive period of the conflict between the U-boat groups and the convoys with their sea and air escorts. Increasingly, the battle was influenced by technical innovations. Most important in this regard were efforts on both sides in the field of signals intelligence.

On 1 February 1942, the Germans had introduced their new M-4 cipher machine, leading to a blackout in decryption that lasted until the end of December 1942. This accomplishment was of limited influence during the fourth phase, because the German U-boats operated individually according to their given orders, and there was no great signal traffic in the operational areas. And when the convoy battles began again, the Germans could at first decrypt Allied convoy signals.

But when Bletchley Park was able to decrypt German signals anew, rerouting of the convoys again became possible, although this was at first limited by rising numbers of German U-boats in patrol lines. In March 1943, the U-boats achieved their greatest successes against the convoys, and the entire convoy system—the backbone of the Allied strategy against “Fortress Europe”—seemed in jeopardy. Now Allied decryption allowed the dispatch of additional surface and air escorts to support threatened convoys. This development, in connection with the introduction of new weapons and high-frequency direction finding, led to the collapse of the U-boat offensive against the convoys only eight weeks later, in May 1943.

This collapse came as a surprise to Dönitz. Allied success in this regard could be attributed mainly to the provision of centimetric radar equipment for the sea and air escorts and the closing of the air gap in the North Atlantic. In a sixth (intermediate) phase from June to August 1943, the U-boats were sent to distant areas where the antisubmarine forces were weak, while the Allied air forces tried to block the U-boat transit routes across the Bay of Biscay.

The change to a new Allied convoy cipher in June, which the German decryption service could not break, made it more difficult for the U-boats to locate the convoys in what was the seventh phase from September 1943 to June 1944. During this time, the German U-boat command tried to deploy new weapons (acoustic torpedoes and increased antiaircraft armament) and new equipment (radar warning sets) to force again a decision with the convoys, first in the North Atlantic and then on the Gibraltar routes. After short-lived success, these operations failed and tapered off as the Germans tried to pin down Allied forces until new, revolutionary U-boat types became available for operational deployment.

The final, eighth phase, from June 1944 to May 1945, began with the Allied invasion of Normandy. The U-boats, now equipped with “snorkel” breathing masts, endeavored to carry out attacks against individual supply ships in the shallow waters of the English Channel and in British and Canadian coastal waters. The U-boats’ mission was to pin down Allied supply traffic and antisubmarine forces to prevent the deployment of warships in offensive roles against German-occupied areas. But construction of the new U-boats (of which the Allies received information by decrypting reports sent to Tokyo by the Japanese embassy in Berlin) was delayed by the Allied bombing offensive, and the German land defenses collapsed before sufficient numbers of these boats were ready.

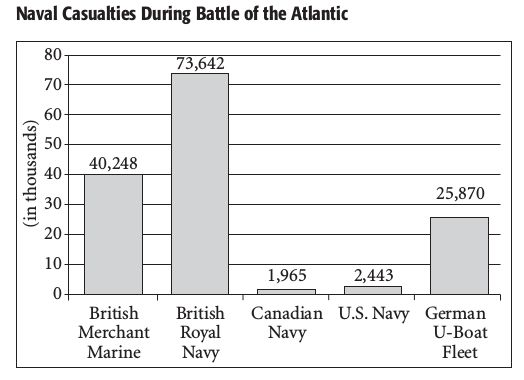

The Battle of the Atlantic lasted without interruption for 69 months, during which time German U-boats sank 2,850 Allied and neutral merchant ships, 2,520 of them in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The U-boats also sank many warships, from aircraft carriers to destroyers, frigates, corvettes and other antisubmarine vessels. The Germans lost in turn one large battleship, one pocket battleship, some armed merchant raiders, and 650 U-boats, 522 of them in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

The Allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic resulted from the vastly superior resources on the Allied side in shipbuilding and aircraft production (the ability to replace lost ships and aircraft) and from superior antisubmarine detection equipment and weapons. Allied signals intelligence was critical to the victory.

References

Beesly, Patrick. Very Special Intelligence: The Story of the Admiralty’s Operational Intelligence Centre, 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books, 2000.

Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War. Vol. 1, The Hunters, 1939–1942; vol. 2, The Hunted, 1942–1945. New York: Random House, 1996, 1998.

Gardner, W. J. R. Decoding History: The Battle of the Atlantic and Ultra. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999.

Niestlé, Axel. German U-Boat Losses during World War II: Details of Destruction. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998.

Rohwer, Jürgen. The Critical Convoy Battles of March 1943. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1977.

———. Axis Submarine Successes of World War Two: German, Italian and Japanese Submarine Successes, 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books, 1999.

Runyan, Timothy J., and Jan M. Copes, eds. To Die Gallantly: The Battle of the Atlantic. Boulder, CO: Westview Press 1994.

Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh. Enigma: The Battle for the Code. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2000.

Syrett, David. The Defeat of the German U-Boats: The Battle of the Atlantic. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

Wynn, Kenneth. U-Boat Operations of the Second World War. Vol 1. Career Histories, U1-U510; vol. 2. Career Histories, U511-UIT25. London: Chatham Publishing, 1998, 1999.

Strategic Bombing

Strategic bombing may generally be defined as air attacks directed at targets or systems capable of having a major impact on the will or ability of an enemy nation to wage war. Airpower proponents have touted strategic bombing as a unique war-winning capability and have used it to justify independent air services.

When World War II began, only two nations had a coherent and committed strategic bombing program: Great Britain and the United States. Although most states with advanced militaries had interest in powerful airpower, continental concerns, resource limitations, or misguided procurement policies hindered most aspirants to powerful long-range bombing forces. Only relatively protected naval powers such as the United States and Britain could afford to focus so much attention on strategic bombing, lured by the strong political appeal of its promise of quick victory at relatively low cost. Both efforts had roots in the experience of the Royal Air Force (RAF) in World War I, when Sir Hugh Trenchard developed tactics and policies for the world’s first independent air service and when talented subordinates such as Hardinge Goulburn Giffard, 1st Viscount Tiverton (subsequently 2nd Earl of Halsbury) pioneered target analysis for morale and material effects to assault the foundations of the German war economy. Although airmen in both countries became aware of the ideas of Giulio Douhet during the interwar years and used them to support arguments for strategic airpower, Douhet had little impact on the evolution of the RAF or the U. S. Army Air Corps.

The RAF continued to pursue Trenchard’s ideal of a massive aerial offensive, assisted by politicians who were willing to fund an aerial deterrent instead of large expensive land armies that could become involved in more bloody continental wars. However, targeting priorities remained vague, and the war would soon reveal the large gap between claims and capabilities.

The Americans took a different approach that can be traced back to Tiverton’s precedents. Although the subordinate army air service’s primary mission remained ground support, a group of smart young officers at the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS) developed a theory of precision daylight bombing of carefully selected targets in the industrial and service systems of enemy economies. Pinning their hopes on the capabilities of new aircraft such as the B-17 Flying Fortress, these airmen expected unescorted self-defending bombers to destroy vital nodes of the enemy’s war economy that would grind it to a halt.

Bombing examples before and during the early days of World War II—in Spain and China and even the German Blitz on London—appeared to demonstrate the ineffectiveness and drawbacks of indiscriminate attacks on cities and to support the superiority of precision tactics. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked the army and navy for munitions estimates for a potential war in 1941, many of those ACTS instructors had joined the Air Staff in Washington. They soon developed a plan called AWPD/1 that envisioned a precision bombing campaign as a key component of the American war effort. When a larger plan that included AWPD/1 was accepted, the U. S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) finally had a justification for pursuing its own independent strategic bombing. They also found it difficult to put theory into practice.

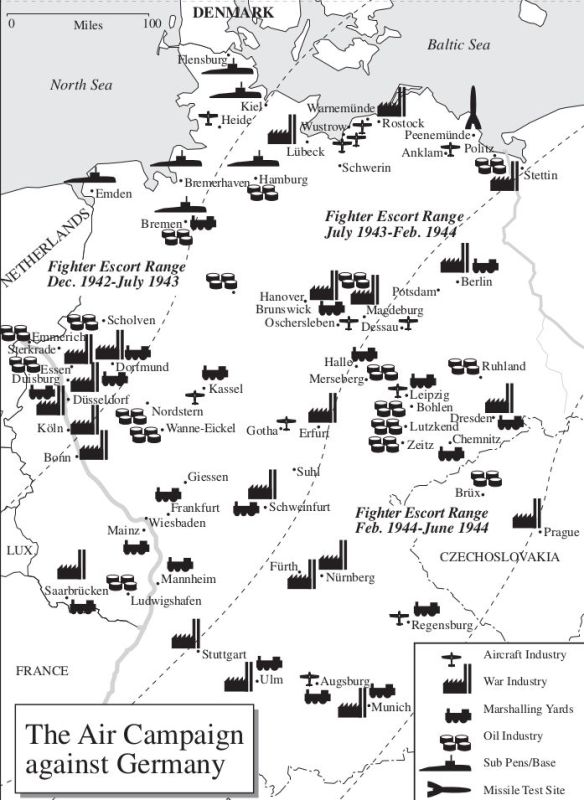

Early British attacks moved from a Tivertonian focus on key systems like power plants or oil to a more Trenchardian reliance on widespread morale effects. Daylight raids proved deadly for RAF Bomber Command, revealing critical deficiencies in the number and quality of their bombers. Operations shifted to the nighttime, but the August 1941 Butt Report concluded that only about one in five aircrews were bombing within five miles of their intended targets. Adapt- ing to the reality of their capabilities, in February 1942 Bomber Command was directed to attack area targets—that is, cities—with the objective of undermining German civilian morale, particularly that of industrial workers. Under the direction of Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Bomber Command built up its strength and obtained better aircraft, especially Halifax and Lancaster four-engine bombers. On 30 May 1942, Bomber Command mounted the first “thousand bomber raid” on Cologne, and in July 1943 it achieved the first bombing-induced firestorm against Hamburg, killing about 45,000 people. However German night defenses also adapted. When Harris decided to mount a full-scale assault on Berlin in late 1943, the Luftwaffe shot down so many British aircraft, and bombing results were so disappointing, that the utility of the whole night area campaign was brought into question.

Meanwhile, the Americans had also encountered difficulties. At Casablanca in January 1943, Allied leaders had agreed to a Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) of round-the-clock attacks. It was rather poorly coordinated, but it did allow each air force to pursue its preferred approach. The most significant USAAF strategic attack of that year was General James Doolittle’s July 1943 attack on Rome from North Africa, which heavily damaged the marshaling yards, limited collateral damage with impressive accuracy, and contributed to the fall of Benito Mussolini’s government. Elements of the Eighth Air Force began bombing the continent from England in August 1942, although they did not fly deep penetration raids into central and eastern Germany until a year later. Losses among unescorted B-17 and B-24 “Liberator” bombers were horrendous, especially during attacks against ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt in August and October 1943. Although the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy joined the daylight campaign in November 1943, the Americans were unable to sustain such attrition. By the end of the year, such deep attacks on Germany were suspended, and it appeared that the Luftwaffe was on the verge of winning the strategic air war in Europe.

Everything changed, however, with the advent of the Allied long-range escort fighter, most notably the P-51 “Mustang.” In mid-February 1944, the U. S. Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) began their “Big Week” attacks against German aircraft factories. The air battles that ensued decimated the Luftwaffe, and by the time of the D-day landings in June, the Allies achieved air supremacy over France and air superiority over Germany. The escort fighters began by sticking close to their bombers, but they proved most effective when they were released to sweep against enemy aircraft in the air and on the ground. Because of the American adoption of radar- directed bombing methods through overcast skies, the Ger- mans had little respite even in poor weather, and their losses were increased by many accidents. Although the strategic bombers had an initial priority to operations in support of the coming invasion, Allied airpower had built up to the point that USSTAF commander General Carl Spaatz could begin sustained attacks against oil targets in May. By the fall of 1944, Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht operations were severely crippled by fuel shortages, and concentrated attacks against transportation networks further limited German mobility and economic activity.

During this period, Harris resisted diversions against “panacea targets” such as oil and remained committed to “dehousing” German workers. However, British bombers did sometimes assist with attacks on oil and transportation targets, and their larger loads of bombs could cause considerable damage. The RAF greatly improved its ability to navigate and bomb at night or in bad weather, and it usually achieved greater accuracy than the Americans under such conditions. Even in clear weather, precision bombing did not approach the image often portrayed in the press of bombs dropping down smokestacks. Usually, all aircraft in the B-17 and B-24 formations dropped their loads together, with intervals set between bombs so they would fall a few hundred feet apart. The pattern therefore covered a wide area. As USSTAF strength increased and targets became scarcer, planners became more tolerant of civilian casualties, adopting less accurate radar-directed bombardment methods in bad weather and hitting transportation objectives in city centers.

At least in Europe, American air leaders remained committed to attacks aimed primarily at economic and military targets instead of at civilian morale, a policy that sometimes caused friction with their British allies. There were also differences over bombing in occupied countries, where the British were particularly sensitive to political repercussions. The Americans were willing to bomb any Axis factory regard- less of the nationality of the workers, whereas the British preferred to strike any German anywhere. The British also favored heavy attacks on the capitals of Axis allies in the Balkans, although the Americans successfully blocked what they saw as an inefficient and ineffective diversion of valuable airpower. Debates about the relative success and morality of RAF and USAAF bombing have continued to the present day.

The differing national approaches also played a role as the war in Europe approached its end, and both air forces sought an aerial death blow to finish the war. The British plan, codenamed THUNDERCLAP , was based on shattering morale by destroying Berlin. That major assault was conducted by the Eighth Air Force on 3 February 1945. Allied concerns about assisting the Soviet advance helped produce the firestorm that devastated Dresden 10 days later. The corresponding American plan, code-named CLARION , aimed to awe the German populace with widespread attacks on targets in every village. It was eventually changed into primarily a transportation assault because of concerns for efficiency, public image, and even morality. The controversy in Great Britain over the Dresden attack was one factor in the suspension of the strategic air war against Germany in April, although it was not as important as the simple fact that Allied bombing forces were running out of suitable targets.

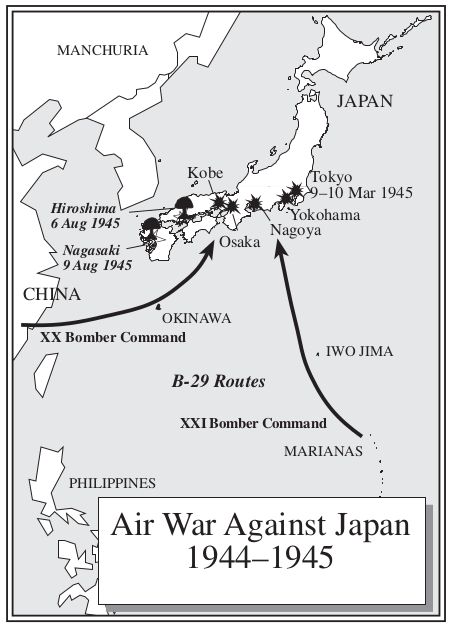

American air leaders such as USAAF commanding General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, who had hoped to build support for service independence by demonstrating the ability of air forces to win wars on their own, still had a chance against Japan. The USAAF referred to the B-29 Superfortress either as a very heavy bomber or a very long range bomber, and by World War II standards it was assuredly both. Every theater wanted to receive the B-29s, but the aircraft’s impressive capabilities and late availability destined it for the Pacific. The Joint Chiefs of Staff established the Twentieth Air Force and named Arnold its “executive agent” to command the B-29s. Although operational control of the aircraft supposedly remained in Washington, in practice the commanders of the subordinate XX and XXI Bomber Commands enjoyed a great deal of independence.

The XX Bomber Command, based in India and China, mounted its first raid against Japan in June 1944. Operation MATTERHORN had little success, even after Arnold assigned his leading troubleshooter, Curtis LeMay, to command it. Bases were too far from key Japanese targets, difficult to supply, and hard to protect from Japanese ground attacks. Additionally the B-29s had been deployed a year early, and testing had to be completed in combat.

More was expected from the XXI Bomber Command based in the Mariana Islands, which was within range of the most important enemy industrial complexes in Honshu. Initial attacks were launched from Saipan in November 1944, but again results were disappointing. Besides technical and logistical problems, the command faced severe weather over target areas that made normal high-altitude precision bombing impossible. Although the vulnerability of Japanese cities to fires was well known and had inspired some USAAF planning for incendiary bombing, there was no meaningful pres- sure from Washington for such tactics. Impatient, however, for a better payoff on a huge investment, Arnold decided in January 1945 to concentrate all the B-29s in the Marianas under LeMay. Although the feisty and innovative air commander received little specific guidance from Washington, LeMay knew that he, too, could be relieved if he proved ineffective.

After trying to make daylight precision bombing work, on his own initiative LeMay adopted a new approach to destroy key industrial targets. His first low-level night area incendiary raid in March 1945 was a spectacular military success, incinerating 16 square miles of Tokyo and killing 90,000 people. Although he would mount some periodic day and night precision attacks, the fire raids dominated LeMay’s air campaign against Japan. Eventually, he burned 178 square miles of some 66 Japanese cities, killing hundreds of thousands of people and causing millions to flee to the countryside. B-29s also dropped the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. MacArthur’s Far East Air Forces contributed three attacks against Kyushu before the Japanese surrender, but the last American bombs that fell on Japan came from the Twentieth Air Force. More than 1,000 planes hit Japan on 14 August, some even after the Japanese radio had announced acceptance of the terms of surrender.

Both the British and Americans conducted postwar assessments of the strategic bombing campaign. The massive U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey compiled an impressive collection of data, although differing personalities and agendas within the survey committees produced several conflicting conclusions. They agreed, however, that the American approach to target- ing was superior to RAF area bombing. The British Bombing Survey Unit relied on the American data along with some of its own, but overall it was not as thorough or comprehensive. It was also critical of the city attacks, but it gave much credit to the RAF-USAAF campaign against transportation.

In retrospect, the most important contribution strategic bombing made in Europe was to defeat the Luftwaffe and ensure that when Allied troops driving across northwestern Europe saw aircraft, they could be certain the planes were friendly. The CBO did not prevent the late-mobilizing German economy from peaking in 1944, but the oil and transportation campaigns had a major impact on degrading it thereafter. Civilian morale did not break, but some British observers have noted that the city bombing motivated German industry to disperse, thus making it more vulnerable to transportation interdiction. More than 700,000 German civilians died from Allied bombing, about the same number who succumbed to the effects of the British naval blockade in World War I. The cost of the CBO was also high for the air forces involved. The USSTAF lost 9,949 bombers, 8,500 fighters, and 64,000 airmen killed. RAF Bomber Command lost 57,000 killed or missing from all causes. In the Pacific, the incendiary attacks and atomic bombs were an important component of the series of shocks that produced the Japanese surrender, although the significance of other factors such as the submarine and naval blockade, as well as Soviet entry into the war, cannot be underestimated.

The World War II strategic bombing experience had several legacies. In the United States, the new U. S. Air Force was born in 1947, espousing a doctrine of air warfare based on the perceived lessons of their air campaigns against Germany and Japan along with the awesome power of nuclear weapons. “Vertical” targeting approaches against key Soviet industries resembled the German oil and transportation attacks, whereas “horizontal” methods based on LeMay’s incendiary campaign were aimed at Soviet industrial concentrations in cities. One planner described the Strategic Air Command’s early war plans as “precision attacks with area weapons.” Since that time, the U. S. Air Force has dedicated itself to the pursuit of real precision, and the extreme accuracy of its contemporary munitions as well as current targeting doctrines have roots in the ideas developed at ACTS in the 1930s. However, while Americans trumpet their ongoing commitment to the principles of precision bombing, the rest of the world also remembers the images of Tokyo, Hamburg, and Dresden.

References

Biddle, Tami Davis. Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Ideas about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

British Bombing Survey Unit. The Strategic Air War against Germany, 1939–1945: The Official Report of the British Bombing Survey Unit. London: Frank Cass, 1998.

Crane, Conrad C. Bombs, Cities, and Civilians: American Airpower Strategy in World War II. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993.

Craven, Wesley Frank, and James Lea Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces in World War II. 7 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948–1953.

Gentile, Gian P. How Effective Is Strategic Bombing: Lessons Learned from World War II to Kosovo. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

MacIsaac, David, general ed. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey. 10 vols. New York: Garland, 1976.

Overy, Richard. Why the Allies Won. New York: W. W. Norton, 1995.

Sherry, Michael S. The Rise of American Airpower: The Creation of Armageddon. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

Webster, Charles, and Noble Frankland. The Strategic Air Offensive against Germany, 1939–1945. 4 vols. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1961.

Armaments Production

Armaments production in each combatant nation, like other economic aspects of the war effort, was intimately tied to each nation’s decisions about grand strategy and the use of military force. Governments analyzed their economic resources and potential industrial mobilization, and they considered how noneconomic factors such as political tradition, cultural institutions, or the limits of state power would modify or restrict those plans. The resulting policies, which Alan Milward calls strategic synthesis, allowed governments to distribute finite resources among the civilian economy, war production, and the armed forces in a more or less rational manner. Put another way, although munitions production was theoretically unlimited, competing demands on resources meant armament creation was often constrained in ways that could not be overcome. The different national limitations on armament expansion help explain why the Allies dominated munitions production during the period 1939–1945.

Limits on armaments production in Nazi Germany were initially political, with the regime explicitly refusing to mobilize the economy too deeply. The Nazis endeavored to prevent a repetition of the experience of World War I, when Imperial Germany suffered political unrest and eventual revolution trying to wage total war. Given Germany’s weaker economic position and resources vis-à-vis its opponents, Adolf Hitler deliberately planned to avoid a long war of industrial attrition. Instead, he planned to wage short, intense campaigns with the limited military forces under development since 1936. Hitler’s guiding strategic concept was to defeat his enemies quickly and avoid military stalemate on the battlefield. The Italian and Japanese war efforts took a similar approach, mainly owing to their inability to compete with Britain and the United States in war production. Indeed, the small size of the Japanese and Italian economies and the drain on Japan of the Sino-Japanese War precluded a major mobilization effort in any case.

The initial Axis strategies called for a high initial investment in modern military equipment; a readiness to conduct short, opportunistic campaigns; and the careful avoidance of long-term economic mobilization. Unfortunately for the Axis powers, the course of the war quickly rendered these plans obsolete.

The western Allied strategic synthesis was also based on the wartime experience of 1914–1918, although different lessons were drawn from that Pyrrhic victory. Although the war itself was viewed as a political and economic disaster, the concept of mass industrial mobilization was taken for granted. By investing in technologically intensive and financially costly—but manpower-saving—armament programs, the western democracies hoped to avoid the mass bloodletting of World War I. Future wars, their leaders believed, would be won by industrial might invested in such programs as the Maginot Line or four-engine bombers, not by running infantry against enemy trench lines. In contrast to the Axis strategy, the Allied strategy was slow to develop, as it took time to gather resources and mobilize industry for war.

As with the western democracies, the Soviet Union also intended to wage machine war on a grand scale, although with a significantly heavier reliance on manpower. Formed out of the experience of the 1919–1920 Russian Civil War, Soviet strategic thinking planned on mass warfare in part because party leaders saw no separation of war, politics, and society. In addition, the policy took advantage of the great resource and manpower reserves available in the Soviet Union. Despite the extreme social and economic disruption caused by industrial and agricultural five-year plans in the 1930s, the experienced and hardened Soviet bureaucracy was confident of a massive industrial response to any future conflict.

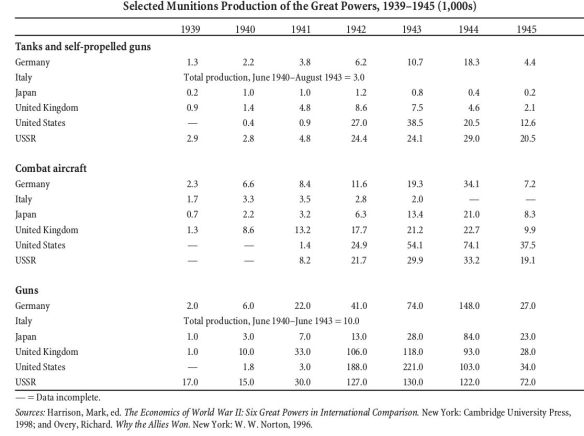

Viewed in these terms, there were four main centers of armaments production during World War II: the western democracies (after 1940, only the United States and British Commonwealth), the European Axis (Germany and Italy), the Soviet Union, and Japan. These economic spheres were in no way equal, however; the Axis powers were at a severe dis- advantage. In 1938, for example, the Allied gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.4 times the size of the GDPs of Axis nations. This ratio is meaningless, however, if such economic power is not translated into combat-ready munitions.

In 1939–1941, the Axis nations enjoyed a significant armaments advantage, as their rearmament programs had started earlier and had concentrated on frontline aircraft, vehicles, and other equipment. In contrast, the western democracies and the Soviet Union were still heavily engaged in long-range rearmament programs at the outbreak of war. The British and the French were building aircraft factories and capital ships in 1940, for example, while the Russians were still focused on engineering, machine tools, and factory construction. Before the fall of France in June 1940, U. S. armament expenditure was quite low, and the munitions industry was backlogged with European orders for machine tools and aircraft. From an armament perspective, the Allies were trailing behind the Axis in the production of actual combat power despite economic superiority, which partly explains the military success of the German and Japanese offensives through 1941. Allied fortunes were then at a low point as entire countries and colonies fell under Axis control, and the Allied GDP ratio over the Axis fell to 2:1 at the end of the year.

From 1942 on, however, the ratio moved steadily against the Axis powers, particularly as the Allies began coordinating armaments production on a massive scale. During 1942, the United States, Britain, and Canada agreed to pool their resources and allocate the production of munitions on a combined basis. The governing idea was to take advantage of each nation’s manufacturing potential, covering any shortfall in other areas through imports from other Allied countries. The British, for example, dedicated a higher proportion of national income to war production than they could normally support (over 54 percent), covering the resulting gap in the civilian economy with imports from North America. Indeed, it was the ability of the western Allies to trade via the world’s oceans, despite the challenge by German U-boats, that allowed the combined production process to work.

By 1944, an immense quantitative mobilization drive nearly doubled the 1938 GDP in the United States (with 42 percent of national income dedicated to the war), steadily increasing the Allied production ratio to 3.3:1 over Germany and Italy and to almost 10:1 over Japan. Combat armament production in the United States alone equaled 50 percent of total world munitions output, with the British adding another 15 percent. Although partly a function of mass production methods, another key to Allied success was the advanced level of economic development in Britain and North America. Well-established transport and other advantages gave the western Allied labor force a 1.4:1 productivity advantage over German workers. The combination led to Allied dominance in the output of a whole range of weapons.

In contrast to the western Allies, the Soviet Union struggled against difficult odds. Although the USSR was much larger than Germany in both area and population, Soviet economic production before the war was only equal to that of Germany, primarily owing to more primitive infrastructure and more primitive machine technology. Following a 25 percent collapse in GDP after the German invasion in summer 1941, the Soviets labored under tremendous pressure to match Axis ground armament production. Over a two-year period, almost half the Soviet economy was shifted from civilian to military efforts, with almost 60 percent of national income allocated to the war in 1943. The ability of the Soviet government to mobilize resources and people proved astonishing, and as noted by Richard Overy, it was this genius for industrial management that allowed the Soviets to pull even with Germany by the end of that year. Despite the accompanying suffering and privation—what Overy called “an exceptional, brutal form of total war”—Soviet workers, helped by Lend-Lease aid from the United States, provided the Red Army with sufficient material to eventually destroy the German armies on the Eastern Front.

Although the German economy was increasingly mobilized for war after 1939, Germany’s prewar notion of limited mobilization restricted centralized control of industrial production. Bureaucratic inertia, the resistance of industry to state control, and a dislike of mass production methods placed Germany in a dangerous position by 1941. Hopes for a quick end to the war were finally dashed that winter, and the German government embarked on a more systematic approach to economic mobilization. The ad hoc style of the past was more or less abandoned, although the mobilization program did not truly get under way until after the German defeat at Stalingrad. Between 1943 and 1944, the proportion of Germany’s national wealth dedicated to the war effort increased from 52 percent to almost 75 percent, which is revealed in the production figures in the Table above. Despite these gains, however, the smaller European industrial base and difficulties extracting resources from conquered territories meant that German war production could simply not keep pace with the Allies. Germany was beset by enemy armies and heavily bombed from the air, and its economy collapsed in 1945.

In comparison with the larger powers, both the Japanese and the Italians fell woefully short in armaments production. Starting with major disadvantages in resources, transportation, and population, neither country was able to mobilize for a long war of industrial attrition. The disruption of imports, confusion in domestic resource allocations, and the loss of overseas supplies such as fuel, coal, and iron ore led to mobilization failures and declining armaments production. Indeed, labor and resource problems meant Italy was never able to commit more than 23 percent of its GDP to the war effort. Japan fared a little better, dramatically raising the low 1941 ratio (27 percent of GDP) in a massive last-ditch mobilization effort (76 percent of GDP dedicated to military outlays in 1944) before economic collapse helped end the war a year later.

The central core of Allied armaments production superiority was resource and industrial mobilization. Firmly rooted in prewar strategic thinking, the Allies refused to be derailed by Axis success during 1940–1941 and continued to plan for a long war of industrial attrition. Though their efforts were improvised and wasteful, the western Allies and the Soviet Union gathered resources from around the world, mobilized workers and industrial plant on a massive scale, and achieved a steady increase in armaments production. The Axis powers, smaller in size and resources even at the height of their conquests, could not match this effort, and this failure helped bring about their defeat.

References

Harrison, Mark, ed. The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Milward, Alan. War, Economy and Society, 1939–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Overy, Richard. Why the Allies Won. New York: Norton, 1996.tlas of the main military and naval events of the Second World War