Warfare in the second half of the 20th century was dominated by the cold war, which for 45 years pitted nuclear superpowers, the United States and Soviet Union, against one another. At the same time, this era also experienced extensive ethnic, religious, and territorial conflict. This often meant that military forces equipped with technologically advanced weapons of mass destruction found themselves in battle with guerrilla fighters armed with makeshift or outdated weapons. The well- equipped warriors did not always win.

The waning days of World War II set new hostilities in motion as the Soviets competed with their Allies to be the first to liberate Axis-held territories in both Europe and Asia. At a 1945 conference at Yalta, three months before Germany surrendered, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, U. S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British prime minister Winston Churchill agreed to a buffer zone between the USSR and Germany. By 1946, Churchill, speaking at a Missouri college, was decrying a Soviet “Iron Curtain” that was turning eastern European nations, including the Soviet sector in eastern Germany, into satellite states while projecting communist influence around the world. The cold war was under way.

Although the United States and Soviet Union never directly attacked one another—hence the term “cold” war—the superpowers engaged in a costly arms race and spent blood and treasure in a series of “proxy” wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. Wars of decolonization that included French Algeria, Dutch Indonesia, and French, British, Belgian, and Portuguese sub-Saharan Africa erupted in many regions still trying to throw off Western imperialism. The United States and the Soviet Union regularly used independence movements as opportunities to outdo one another by providing intelligence, arms, and covert assistance to their presumed allies. Both “proxy” and “decolonizing” wars played out in a bipolar world in which the Americans and Soviets each pressed the rest of the world’s nations to take their side. Many did so; others, including India, precariously maintained nonaligned status.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union were permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, but they also took steps to secure their own allies. NATO—the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—founded in 1949, became a mutual security body prepared to respond militarily to possible Soviet incursions. Moscow responded in 1955 to NATO’s admission of West Ger- many by creating the Warsaw Pact, a mutual defense agreement between the Soviet Union and most eastern European nations in the Soviet orbit.

The Soviet Union intervened militarily to crush revolts in Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), and Poland (1981) and built the Berlin Wall to prevent East Germans from escaping to the West. The United States also intensified efforts to control client nations in Central America, sometimes intervening militarily to prevent the emergence there of reform movements that were, or seemed to be, inspired by communism. Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro’s embrace of the Soviet Union after 1959 was a rare failure of U. S. influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Arms Race. The most significant but least-used weapon of the cold war era was the nuclear bomb and its associated adaptations. After the Soviets fabricated their own A-bomb in 1949, other nations were soon preparing to join the nuclear “club.” Since then, Britain, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, South Africa, and North Korea have built bombs or are believed to have developed bomb technology, despite international efforts to check nuclear weapons proliferation. In 1951, the United States tested an even more powerful hydrogen, or H-bomb and began expanding its fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. As the arms race intensified, both sides turned to rocket technology to create intercontinental ballistic missile systems; virtually all of these were designed to drop nuclear warheads on enemy targets or fire them from submarines.

Many historians now agree that this bilateral binge of nuclear weapons stockpiling was a major reason why the United States and the Soviet Union managed to avoid going to war with each other. The cold war weapons buildup that produced what came to be called MAD—mutually assured destruction—certainly caused anxiety. Americans were urged to build backyard fallout shelters to protect their families from radiation.

During the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, U. S. President John F. Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushchev squared off over Soviet installation of nuclear weapons in Cuba. War was narrowly averted, but the likelihood that both nations could suffer deaths and damage of unprecedented magnitude helped to defuse the impasse. In 1963 Kennedy and Khrushchev signed a treaty banning above-ground nuclear testing; by the 1970s, the two nations were negotiating agreements to slow or even reduce nuclear weapons development

After 1950, the U. S. Air Force emerged the big winner in the internal Pentagon race for respect and resources. The biggest, most expensive improvements in both offensive and defensive weaponry focused on manned and unmanned aircraft and missiles. Aircraft carriers and submarines dominated the seas, while versatile armored helicopters took on important combat roles. After the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik in 1957, the first satellite in orbit, the idea of “air” power took on an outer space dimension. Although the perceived Sputnik military threat fizzled, in 1983 Ronald Reagan, America’s last cold war president, proposed a strategic defense initiative, dubbed “Star Wars,” to shoot down Soviet missiles from positions in space.

Proxy Wars. Three major conflicts between 1950 and 1989 demonstrated attempts by the two superpowers (and Communist China) to “win” the cold war militarily and ideologically. These were the Korean War (1950–53) and Vietnam War (1954–75), in which U. S. troops played a leading role, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979–89). None of these conflicts proved very productive for the superpowers.

With the blessing of the United Nations (during a Soviet boycott of the Security Council), the United States assembled a multinational force to repel efforts by Communist North Korea to conquer pro-Western South Korea. Soon, the new Chinese Communist regime came to the aid of North Korea, complicating any chance for a United Nations–led victory. This war ended with an armistice that never became a peace treaty. Hostilities continued to break out along the DMZ (demilitarized zone) separating North and South Korea.

Soviet intervention in a civil war–wracked Afghanistan ended 10 years later in a failure so profound that it became a factor in the breakup of the Soviet Union soon after. The U. S. government, interpreting the Afghan conflict through a cold war lens, provided the latest weapons, including Stinger missiles, to local warlords. A decade later, these weapons would reappear as disaffected ethnic and religious groups in Asia and the Middle East mounted anti-American and anti-Russian attacks.

Vietnam was the longest of these “proxy” contests and, for a time, made Americans question national power and the U. S. role in a world of nations. As Japan withdrew from its Asian conquests at the end of World War II, the French tried to resume colonial control in Indochina. Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, a Communist, sought independence. By the time France withdrew in 1954 after a major defeat at Dien Bien Phu, the United States had assumed the role of protecting the southern sector of politically divided Vietnam from its “red” brethren in North Vietnam.

For 10 years U. S. involvement in South Vietnam drew little public attention and was carried out by relatively small numbers of military advisers and intelligence agents. These Americans were supposed to strengthen South Vietnam’s military and political structures to prevent what President Dwight D. Eisenhower called the “domino effect.” This was the idea that communism had to be contained—ideologically if possible, militarily if necessary—wherever it appeared. The U. S.-backed South Vietnamese government headed by Ngo Dinh Diem was corrupt and unpopular. In 1963 a U. S.-instigated military coup assassinated Diem. In 1964, an apparent clash between North Vietnamese vessels and a U. S. warship spying in North Vietnam’s Gulf of Tonkin gave President Lyndon B. Johnson a free hand in Vietnam, despite his having no congressional declaration of war.

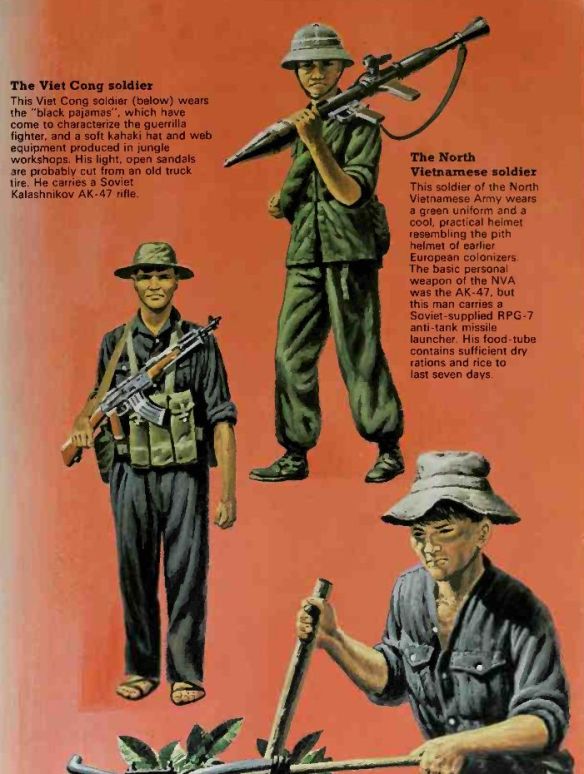

Militarily, Vietnam was a conflict between a massively armed superpower and guerrilla fighters known as the Vietcong. Aided by regular North Vietnamese troops and outfitted with Chinese and Warsaw Pact–supplied weapons, these fighters used their knowledge of Vietnam’s terrain, jungle climate, and people to fight on, despite U. S. attacks with napalm, a deadly defoliant, and air raids that dropped 8 million tons of bombs on Vietnam, more than any other country had ever experienced.

One collateral casualty of Vietnam for the United States was the end of its system of universal military service. After World War II, the United States continued mandatory military training for young men. As a result, the U. S. Army expanded to 3.5 million soldiers. As manpower needs in the undeclared war in Vietnam required more American troops—peaking at 541,000 in 1969—resistance to the war also increased. College students used generous deferment policies to postpone conscription; when that failed, a friendly doctor might issue a diagnosis of disease or mental illness. Draft protesters publicly burned their Selective Service documents, and thousands fled, mostly to Canada and Sweden, to avoid the draft.

Warfare in a Postcolonial and Post–Cold War World. As the Soviet Union unraveled between 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down, and 1991, when its last premier, Mikhail Gorbachev, resigned, some thought, briefly, that a time of peace might be at hand. In fact, the demise of a world order shaped by two superpowers helped intensify existing ethnic, religious, and political rivalries and created new “hot spots” around the globe. As old-style colonialism collapsed, especially after 1960, new wars over boundaries and resources erupted in Africa and other formerly colonized regions where Western control had distorted national development. Tribal massacres in Rwanda and the Darfur region of Sudan were only the bloodiest outcomes of warfare also afflicting Congo, Liberia, and much of West Africa. “Ethnic cleansing” occurred in Europe, as Yugoslavia, once an independent socialist state, broke into warring religious and ethnic groups. India and Pakistan clashed over the disputed territory of Kashmir, becoming competing nuclear powers in the process. Persistent conflict between Israel, founded in 1948 as a Jewish state, and its Arab neighbors remained a major danger to world peace.

Indeed, events in the oil-rich Middle East became even more central in the post–cold war years. Religious conflicts between some Islamist organizations and other world religions were at the heart of warfare conducted not by national armies but by small, dedicated groups using terrorist tactics, including suicide bombing, to achieve their aims. Terrorism was not a new method of warfare— Irish nationalists for years had used terror tactics against Britain—but it seemed especially effective against nations whose strength lay in conventional methods of warfare.

Russian troops laid waste to the separatist Islamic region of Chechnya, but found that this neither ended Chechen guerrilla actions nor protected Russian civilians from terror attacks, even in Moscow. On September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda, an Islamist group based in Afghanistan, used 19 operatives, armed only with box cutters and just enough training to pilot commercial jets, to bring down New York City’s World Trade Center and seriously damage the Pentagon outside Washington, D. C. Smaller deadly attacks in Madrid and London were later perpetrated by al-Qaeda or similar non-national terrorist groups. The U. S.-led 2003 Second Gulf War against Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq in 2003 was a triumph for America’s sophisticated weapons but faltered amid low-tech attacks committed by warring factions upon each other and U. S. forces.

As the 21st century got under way, the rapid spread of technology and almost uncontrolled sales of arms and possible “weaponized” biological and chemical agents seemed to be changing warfare from nation-state projections of power within formal rules of engagement into a dangerous free-for-all among disgruntled nations, regions, and even small groups of individuals destabilizing the world.