Fueled by imperial rivalries, powerful new weapons, enlarged manufacturing capacity, and broader military conscription, the wars of the first half of the 20th century included the two largest armed conflicts in world history. The Great War of 1914–18, later renamed World War I, followed by World War II (1939–45), reshaped the global order, but neither proved to be the “war to end all wars.”

The years 1900 to 1914 were the high point of European and, to a lesser extent, American and Japanese colonial adventurism. Partitioning a war-weakened China into spheres of economic and political influence, the great powers also competed for control of many other resource- and labor- rich regions of Asia, Africa, and Oceania. At the same time, European powers used their industrial might to accelerate an arms race and developed intricate agreements and alliances to protect their interests at home and in their colonial holdings.

In the summer of 1914, a Serbian nationalist’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, set these alliances in motion and led directly to the Great War. The war pitted the Allied Powers—France, Russia, Britain, Japan, and other nations, eventually including the United States—against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the fading Ottoman Empire.

New Strategies. The Great War was a field laboratory for a range of new weapons and new strategies for deploying troops. For the first time, aircraft played a significant role. They were used by both sides for aerial reconnaissance and to drop explosives on enemy forces. Germany’s successful use of torpedo-equipped U-boats, mainly to harass enemy shipping, was the first time that submarine technology, developed late in the 19th century, was taken seriously as an important tool of war. Breach-loading, quick-firing field guns made infantrymen more deadly; howitzers capable of firing five or more rounds of shells a minute were deemed responsible for 70 percent of the war’s 9 million troop deaths. Radio, newly developed, revolutionized the ability of troops and commanders to communicate in real time. Near the end of the war, the British first used internal combustion–powered armored tanks to breach German positions. Tanks were better able to protect drivers and rolled easily over barbed wire and other obstacles—they became standard equipment in subsequent conflicts.

As both sides relied on massed infantry assaults and protected their men behind trenches dug into battlefields, stalemate became a frustrating and dangerous enemy, especially on the war’s western front. The trenches indeed protected soldiers, but they also prevented them from effectively engaging the enemy in battle. To leave the trench was to face likely attack by a sniper in the opposing trench. The trenches filled with water and filth, causing illness and injury. Chemical and biological weapons, such as deadly and debilitating chlorine gas (its use has since been outlawed under international law), were a particular threat to troops trapped in trenches. The introduction of tanks late in the war would help to overcome this standoff.

As the war dragged on, inflicting huge casualties in such battles as Gallipoli in 1915 and Verdun and Somme in 1916, Central Power conquests in Russia, Serbia, and Romania, combined with internal unrest, led to Russia’s withdrawal and its separate peace with Germany. As the Russian Revolution intensified, Romanov czar Nicholas II abdicated in March 1917. A month later, the United States, jolted by submarine attacks and outraged by a secret German plan to help Mexico regain territory lost to the United States, declared war on the Central Powers. Although it would be 1918 before significant numbers of U. S. troops began fighting with the Allies in Europe, the effect of fresh manpower helped bring about Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication on November 9, followed by the armistice on November 11, 1918, that ended the war.

The Great War, ended by the controversial Treaty of Versailles with Germany and by other treaties with allies, solved few problems and almost certainly created new ones. Despite the creation of a League of Nations (which the United States declined to join) and a series of disarmament proposals and conferences, both rearmament and colonialism continued. Although Ireland would win its long-sought independence from Britain in 1921, other colonial struggles remained unsettled. In fact, Britain and France found new opportunities to dominate the Middle East in the remains of the former Ottoman Empire.

Russia, now under a Communist regime, fought off a post-armistice invasion by its alarmed former Allies and set about securing what would become a two-continent Soviet Union in Europe and Asia, while leader Joseph Stalin tightened his totalitarian rule. This almost guaranteed unrest in eastern Europe and new confrontations with Japan. Germany’s new Weimar Republic struggled to recover from the lost war, and from the Versailles Treaty demands for billions in war reparations (although never collected in full). Austrian-born Adolf Hitler would brilliantly use post–Great War political and social conflict and German bitterness and resentment to obtain power as leader of the new National Socialist, or Nazi, Party.

Civil war in China in the 1920s and 1930s emboldened Japan to seize Manchuria in 1931 and launch a full-scale invasion of China in 1937. Japanese brutality toward their victims, for example, in the Rape of Nanjing (Nanking), equalled the horrors of Nazi atrocities. Meanwhile, Hitler began rebuilding German military power, in direct defiance of treaty provisions, meeting only token resistance from the former Allies. With his Fascist ally, Benito Mussolini of Italy, Hitler tested his new weapons by intervening in the Spanish civil war on the side of Fascist insurgents led by Francisco Franco. As a new war threatened in Europe, France responded by building its Maginot Line, a system of fortifications. Some 3,000 Americans defied offi cial U. S. neutrality to fi ght against Franco in Spain. Otherwise, the predominant sentiment in France and Britain was appeasement of the aggressors.

Poland Attacked. World War II in Europe began on September 1, 1939, when German panzer divisions of massed tanks and mobile artillery invaded Poland days after a nonaggression pact between Hitler and Stalin gave Hitler a free hand in eastern Europe. By June 1940, Hitler’s forces had occupied France, where they installed the Vichy government, which was subservient to Germany, and controlled most of Europe, while Britain fought virtually alone. That September, Germany, Italy, and Japan created a formal alliance known as the Axis. In June 1941, German forces invaded the Soviet Union, violating the 1939 pact.

From the outset, the fighting forces relied heavily on tanks, especially the reliable U. S. Sherman Tank, and air power. Battleships were central to earlier conflicts; in World War II aircraft carriers became the most significant fighting innovation because they enabled the simultaneous projection of both sea and air power. When Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, bringing the United States into the war, the huge loss of life and warships at the Hawaiian air base was partially offset by the fortunate deployment elsewhere of America’s aircraft carriers. Submarine warfare, especially in the Atlantic Ocean, expanded in importance for both the Allies and the Axis, inflicting huge damage on commercial shipping and enemy navies. Military aviators, including those from Britain’s Royal Air Force, Germany’s Luftwaffe, and the U. S. Army Air Force, depended on heavily armored bombers capable of flying long distances with heavy loads of bombs and on nimbler fighter planes to repel enemy attackers. Radar technology, first made functional in the 1930s by British and American scientists, helped the Allies detect submarines and obtain advance warning of air attacks, somewhat defusing the effectiveness of both these tools of war.

Total Global War. World War II was a global war and a total war with fronts in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. As the Allies struggled in the early war years, the Soviet Union bore the brunt of Axis attacks in eastern Europe; Britain held out in the west, while the United States deployed most of its power against the Japanese in the Pacific. In 1942, the Allies began to have successes, especially at Midway Island in the Pacific, in North Africa, and in the USSR, where the Soviet Union, despite huge military and civilian casualties, turned back Hitler’s siege of Stalingrad in January 1943. The Allies’ “Operation Overlord” D-day invasion of Normandy beaches in June 1944 finally opened a second European front. It took almost a year of hard fighting before converging Soviet troops and British and American forces were able to force Hitler’s suicide and Germany’s surrender in May 1945.

This total war claimed an unprecedented number of civilian casualties and displaced persons. Millions were killed or wounded by military action. Millions more were victims of deliberate murder, overwork, or starvation. Stalin sent millions of Soviet citizens into forced labor camps. Hitler turned much of occupied eastern Europe into a Nazi forced labor camp and deliberately exterminated “undesirables,” including 6 million Jews, in what became known as the Holocaust. Japan imposed brutal measures on occupied Asian territories, especially Korea and China. In the United States, 120,000 West Coast Japanese, most of them U. S. citizens, were forced to leave their homes and businesses for internment in rural detention camps for the duration of the war.

On both sides, the war mobilized millions of volunteers and conscripts and brought more women than ever before into the industrial economy. The United States instituted its very first peacetime draft in 1940. African Americans, as they had in every American war since the Revolution, fought in racially segregated units commanded by white officers. This changed in 1948 when U. S. president Harry Truman controversially ordered the U. S. armed forces to desegregate. Some 30,000 Japanese Americans served, but they were sent to Europe, not the Pacific theater. As had also been true in the Great War, political officials for both the Axis and the Allies created massive public relations campaigns designed to demonize their enemy, preserve home front morale, and encourage obedience to various rationing and work initiatives.

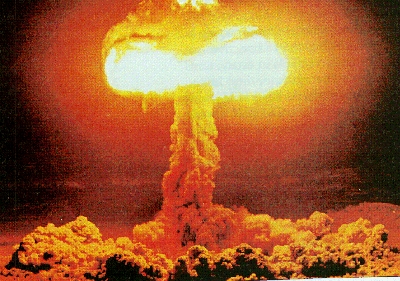

During the final two years of World War II, both sides would introduce controversial new kinds of weapons. Germany’s blitz of London with manned bombers was succeeded in 1944–45 by even more terrifying unmanned medium-range rockets, the V1 and V2. Allied fire bombings of Dresden, Germany, and Tokyo incinerated large parts of both targets, killing thousands of civilians. But the most controversial weapon by far was the atomic bomb, or A-bomb, used twice on Japan by the United States in August 1945. An experimental weapon created during the war by America’s top secret Manhattan Project, this bomb could be delivered by a small plane and destroy entire cities, as it did Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Conventional bombing had killed even more people; what made the A-bomb so terrible was the radiation it emitted, sickening survivors and causing their deaths or harming unborn children weeks or even years later. After the two A-bombs were dropped, Japan surrendered in September 1945, bringing World War II to its end.

Warfare continued, however, despite the creation of the United Nations, a new global peace- keeping body headquartered in New York City, and well-publicized Nuremberg War Crimes and Tokyo International Court Trials of surviving Axis leaders. In 1949, forces led by Mao Zedong, which had been nurtured during Japan’s invasion of China while the Nationalist forces were ground down, finally won the Chinese Civil War, defeating China’s U. S.-supported Nationalist government and installing a communist regime. Anticolonial wars threatened the remains of British, Dutch, and French colonial interests. Britain granted independence to India in 1947, but most African and Asian nations would only gain independence in the years following 1950.