The invaders

While Stalin continued to place his faith in the complex

mechanisms of his foreign–political axioms, the German preparations rolled on

undisturbed. By June 1941, the Wehrmacht’s leaders had gathered 3.3 million

soldiers on the borders with the Soviet Union. The total number of German

soldiers deployed during the course of the war in the East is estimated at

around ten million. In other words, it was the largest military force Germany

had ever assembled. But it would not be large enough.

The explanation for this is simple. The economic and

demographic resources available within the German area of control were simply

too small for a war on multiple fronts against a coalition as strong as the

Allies. But can the course of a war really be explained with only a handful of

statistical comparisons? Military reality is often far more complex. Suffice it

to mention only the German campaign in the West and that, in the Soviet Union,

too, the Wehrmacht was initially triumphant. Why was that?

The majority of the German soldiers believed that the war

was for a good cause, at least at first. They were also experienced, hardened,

reasonably solidly equipped, well trained, and excellently led at the tactical

level; benefiting also from the element of surprise made their initial success

secure. These soldiers were used to fighting a land war, something that applied

equally to most members of the Luftwaffe, which made up 27 per cent of the

invasion force. By contrast, the German Navy was never more than peripheral to

the Eastern campaign. Its deployment was restricted to the Baltic and Black

Seas.

Although Operation Barbarossa was primarily a land war and

although this was where the German Armed Forces had felt at home since time

immemorial, the war also rapidly exposed the weak links in the Wehrmacht’s

professionalism. It was in this endurance test that it became apparent how

improvised the German forces truly were. They had been shrunk to merely 115,000

men between 1919 and 1933, after which a rearmament programme had begun in

which those cadres were divided again and again so as to have their numbers

supplemented with hundreds of thousands of conscripts, volunteers, and

reactivated veterans of the First World War, all furnished with first German

and then increasingly captured military equipment, which, however, proved less

and less equal to demand, in both quantity and quality. The result was

ultimately a complex conglomerate of units and divisions that differed greatly

in professionalism, equipment, and attitudes.

The backbone of the German Eastern Army consisted of the

Infantry Divisions, thoroughly capable units of over 17,000 men whose provision

with vehicles, anti-tank guns, and heavy weapons was, however, all too limited.

Since the Infantry Divisions soon lost their modest pool of vehicles, they

marched and fought as in the Napoleonic era—on foot or by horse and cart, with

rifles and artillery. The German Eastern Army began Operation Barbarossa with

750,000 horses; during the course of the war, the demand for this archaic form

of transport grew steadily, along with the concomitant need for carts.

The Eastern Army’s 3,350 panzers and 600,000 motor vehicles

(in June 1941) had instead been concentrated largely in the Motorized

Divisions. These few elite groups were to tear open the enemy’s front line and

so make a blitzkrieg possible. The German armies at the time were rightly

compared to a lance—a piercing, hard, short point on a long wooden shaft. With

a relatively small arsenal of modern weapons—that is, armoured vehicles of all

sorts, motorized artillery, rocket launchers, modern radio and permanent air

support—the Wehrmacht was able to produce the local superiority that swung

battles—rapid raids independent of the infantry’s marching speed. But this potential

was soon exhausted, actually as soon as autumn 1941.

Also insufficient right from the first were the units

intended to control the enormous occupied zone. The soldiers deployed here were

those who were no use at the front: the older year groups or those with some

slight physical impairment. Their training was poor. ‘The great mass of the

battalion has never fired live rounds,’ complained the leader of one of these

divisions in spring 1942. And these Security Divisions, which were weaker than

their regular Infantry equivalents in both men and material, were supposed to

patrol a gigantic occupied zone the majority of which was completely

undeveloped. A Security Division of around 10,000 men could be responsible for

an area of around 40,000 square kilometres, an area half the size of Scotland.

It is easy to see that their mission was a futile one.

The best way to visualize the organization and proportions

of the Eastern Army is perhaps a breakdown of the forces in June 1943. At that

point, there were 217 German divisions deployed on the Eastern Front, of which

154 were infantry, 37 motorized, and only 26 allocated for maintaining the

military occupation. Truly modern battle groups able to call on the whole

repertoire of modern armaments remained the exception. This also draws

attention to something else that would be important later: most German soldiers

experienced the war at the front and not in the hinterland.

The Eastern Army had to absorb terrible losses as early as

summer 1941. For an army that was lacking strength in depth and particularly

reserves of personnel, that was catastrophic. Without the help of Germany’s

allies, even the summer offensive of 1942 would not have been possible.

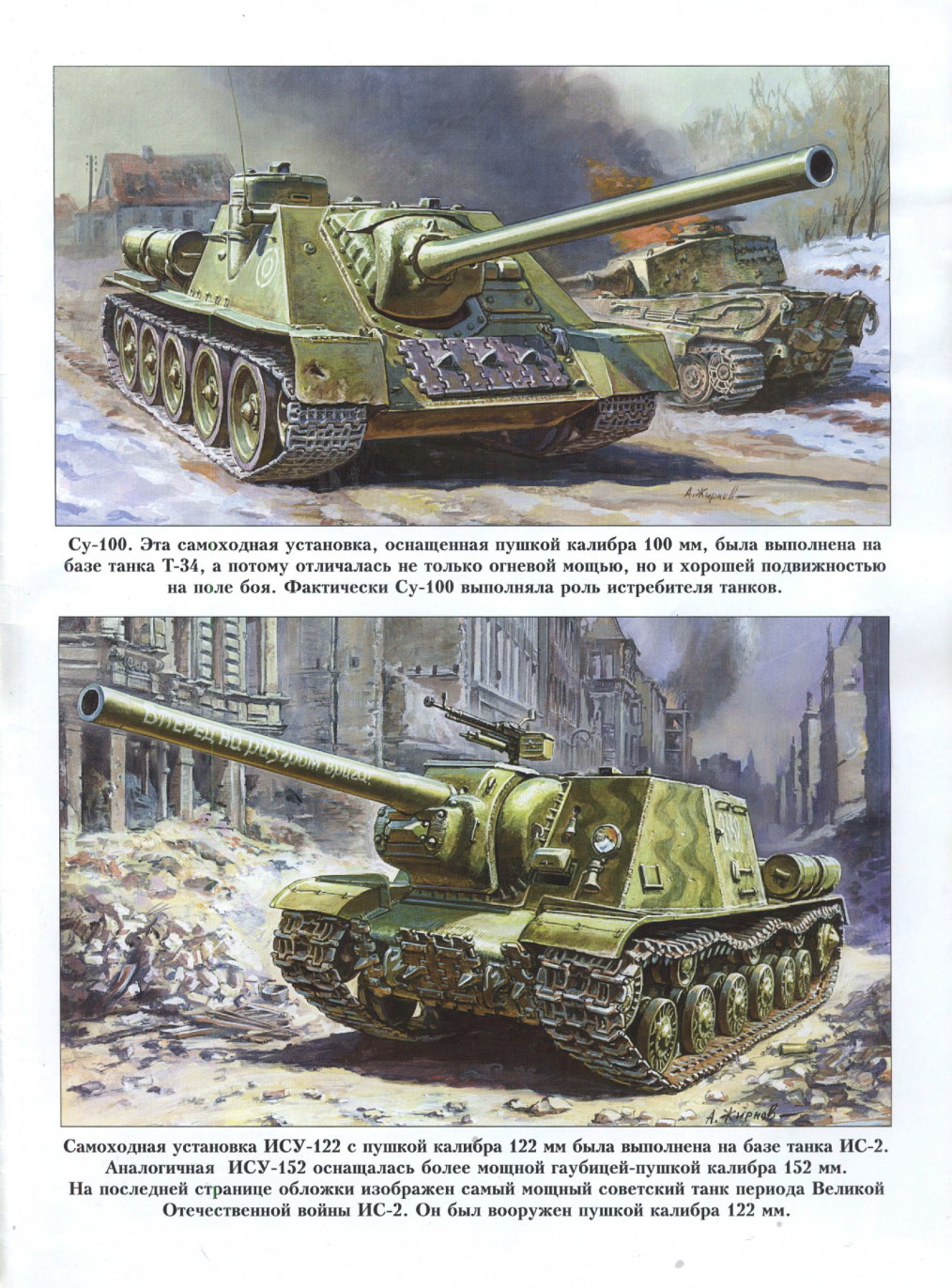

Nonetheless, from 1943 the Eastern Army was supposed to experience a kind of

‘second spring’ after the beginning of the ‘armaments miracle’ presided over by

Albert Speer. It was only then that the heavier and technologically modern

panzers were put into action—the Tiger, the Panther, and the various tank

hunters. With the introduction of assault rifles and the anti-tank panzerfaust

in 1944–5, the infantry also began to hit harder. But by then it was too late

for this modernization drive to alter the course of the war.

From winter 1941–2 onwards, the Eastern Army was living from

hand to mouth both militarily and logistically. Its situation was defined by

the continuous improvisation with which it managed to postpone the great

military catastrophe until summer 1944. What rescued the divisions fighting in

the East time and again were their cohesion and their professional ability,

along with good troop leadership. That compensated for a lot—for their

horrendous losses, their increasing immobility, the ever more bizarre

instructions from the Führer headquarters, and, finally, the growing

superiority of their opponent. As early as 1941, a German regimental commander

found the battles so fierce that ‘the German soldiers who survived were

hardened into as powerful a troop such as we have rarely had’. They were

unusually cohesive, and desertions remained very rare on the Eastern Front

until the winter of 1944–5. The reasons for that were doubtless a tough diet of

authority and obedience, along with an enemy whom most of the Landsers, the

ordinary troops, rightly feared. Even more effective were the attitudes that

ensured their continued commitment to such ideals as comradeship, courage, and

the fatherland, and so also to the world of military organization. On top of

that, the lie disseminated by German propagandists, that the attack on the

Soviet Union had been a pre-emptive strike, was long believed, particularly

under the influence of a Nazi ideology whose mechanisms of social engineering

had succeeded in leaving their imprint especially on the younger soldiers.

In general, the perspectives of the Wehrmacht soldiers were

far more diverse than one would initially imagine, often simply because it

consisted of differing generations. Of greater consequence was that these men’s

attitudes necessarily changed under the pressure of a war whose reality

corresponded ever less closely to the grandiloquent promises of German

propaganda. In the end all this was outweighed by the knowledge or suspicion of

their own guilt, whether individually or nationally, and also by the conviction

that their homes had to be defended against the ‘Bolsheviks’, simply because

the front now ran right through their own homeland. That, too, explains why the

German Eastern Army never disintegrated. But soldiers do not usually have the

opportunity to determine their own actions, and those actions cannot be

explained just by the soldiers’ thinking. The external factors were far more

powerful: the army, the dictatorship, and a war by which the soldiers were held

captive—no less so than their Soviet enemies.

Allies

It is often overlooked that the German invaders did not

fight alone in the Soviet Union; by their side stood many allies from

throughout Europe. In 1943, every third man in uniform on the German side was

not a German. ‘It can hardly have been more colourful in the medieval armies,’

as one German medic said of his ‘Cavalry Squadron East’, which recruited from

Red Army prisoners of war. There were various reasons why the Eastern Army

became an international force; it was a consequence of both state agreements

and individual decisions, and so there were allied troops, European volunteers,

and local collaborators.

This had not been envisaged. Particularly in a war such as

this one, Hitler wanted to retain the maximum possible freedom of decision,

which entailed not having to take account of allies whom experience had shown

to be often weak or difficult. Only two states were supposed really to

participate in the great Eastern conquest: Finland and Romania. Although both

pursued territorial interests within the Soviet Union, they did not infringe on

the German sphere because they were engaged only at the furthest peripheries of

the Eastern Front, in regions that would have anyway presented problems for the

Wehrmacht. The Romanian and especially the Finnish armies thus maintained a

relatively high level of autonomy. The other partners Hitler desired, Turkey

and Bulgaria, were sufficiently perspicacious to keep themselves out of this

undertaking, Turkey entirely, Bulgaria on the whole.

There was little room for any other allies in Hitler’s plans

for his future Lebensraum. This made things far from simple, not least because

the German invasion of the USSR was very popular in some parts of Europe; it

tapped into a significant anti-Bolshevik impulse, a passion for war, and a naked

greed for the spoils of conquest. ‘Your decision to take Russia by the throat

has met with enthusiastic approval in Italy,’ Mussolini telegraphed to Hitler

in summer 1941. Italy, Hungary, Slovakia, and Croatia, all official German

allies, did not miss the opportunity to be among the first divisions entering

the Soviet theatre of war. Mainly third rate in their training and equipment,

these troops were initially left in the lee of larger military events.

Only in 1942, when the German leadership realized how

dependent it was on outside help, were whole armies of Romanians, Italians, and

Hungarians included in the second German offensive. They were to pay a high

price for being so hopelessly out of their depth, and their German partners

seldom showed any gratitude for their contribution. After the debacle of

Stalingrad, it was bitterly recorded on the Italian side that their own

soldiers had starved while the Germans provided them with ‘not the slightest

assistance’. ‘If an Italian soldier approached a German kitchen and asked for a

little food or water, he was greeted with pistol shots.’ In total, 800,000

Hungarians, 500,000 Finns, 500,000 Romanians, 250,000 Italians, 145,000 Croats,

and 45,000 Slovakians fought in the Soviet Union. Most of them were there

because they had been ordered to go.

The rest of Europe, by contrast, was represented by

volunteers. Their contingents were far smaller and more heterogeneous, but, as

a rule, also more motivated. For them, taking up arms on behalf of Germany—out

of political conviction, a lust for adventure, or a need for belonging and

social advancement—was a personal choice. The Germans first reacted

reluctantly, despite the lip service they paid to shared ideology. But opinions

soon changed as German losses mounted, and they began to overlook the fact that

the racial criteria of Nazism were supposed to apply equally to foreign

volunteers. The German recruiters initially distinguished between

‘non-Germanic’ volunteers, such as Spaniards, Croats, or Frenchmen, who mainly

became part of the Wehrmacht, and ‘Germanic’ volunteers, Danes, Norwegians, or

Dutchmen, who were usually assigned to the Waffen SS so as to form the core of

a future ‘Pan-Germanic Army’. This was also the destination for the huge supply

of ethnic Germans living outside Germany, most of them in south-east Europe.

The majority, however, ended up in the army, not as volunteers, but because of

international bilateral agreements. Although the Germans significantly

intensified the propaganda aimed at recruitment, not least because of the great

symbolic and political value of a united Europe fighting against Russia, the

results fell far short of what they hoped. The numbers of foreign volunteers

deployed on the Eastern Front between 1941 and 1945 are estimated as the

following: 47,000 Spaniards, 40,000 Dutchmen, 38,000 Belgians, 20,000 Poles,

10,000 Frenchmen, 6,000 Norwegians, and 4,000 Danes, as well as smaller groups

of Finns, Swedes, Portuguese, and Swiss.

The final group, of a quite different military and political

significance, was made up of the collaborators. The figures alone make that

clear. It is estimated that 800,000 Russians, 280,000 people from the Caucasus,

250,000 Ukrainians, 100,000 Latvians, 60,000 Estonians, 47,000 Byelorussians,

and 20,000 Lithuanians bore arms on the German side. This happened, again, for

a range of varied reasons. For the soldiers from the Baltic, the Caucasus, and

the Ukraine, nationalist and anti-Bolshevik motives played an important role;

while the appearance of Russians, mainly as ‘Hiwis’ (Hilfswillige, voluntary

assistants), was often the result of coercion or straightforward need, and only

secondarily as a consequence of personal conviction or political commitment.

Just as heterogeneous as the origins and mentalities of

these military collaborators were their willingness and ability to fight.

Looking back on them, one of their German commanders wrote that a fifth ‘were

good, a fifth bad and the other three-fifths inconsistent’. This became even

more obvious because they were grouped together by nationality, first the

Baltic soldiers, then the people of the Caucasus, the Ukrainians, and, by the

end of the war, the Russians, too, in the so-called Russian Liberation Army.

Nevertheless, odd remnants of an imagined European crusade against Bolshevism

were able to outlive the downfall of Nazi Germany. There were exiles and

right-wing extremists who continued eagerly to propagate these fantasies after

1945, as well as a number of scattered anti-Bolshevik guerrilla groups that

maintained their activities in the Baltic countries and the Ukraine until well

into the 1950s.

The real problem with all of this was that any form of

military or political power-sharing was in diametrical opposition to the course

plotted by the Nazi leadership. Their plans would have alienated even the most

enthusiastic collaborators, because Hitler remained fundamentally indifferent

to the ‘hearts and minds’ of his helpers from Eastern Europe, though it was

precisely those Eastern Europeans who could have been the most important. The

Führer, despite all propaganda material to the contrary, was stubbornly

unwilling, right to the last, to make use of the opportunity they presented and

come up with a viable political concept to underpin the oft-trumpeted ‘New

European Order’. Although elements of the Wehrmacht, the ministerial

bureaucracy, and even the SS High Command increasingly came to rely on them,

the Eastern European collaborators were kept on a short leash, entirely

dependent on German instructions.

Nevertheless, the fight against the Soviet Union was not

Hitler’s war alone. Ultimately, it was a German war that was also, to some

extent, a European one, in which many expectations and intentions were bundled

together, some of them entirely incompatible with one other.

The Soviet Union’s land and people

It seemed almost endless, the country that the Wehrmacht

invaded in summer 1941, and that was another reason for the German defeat: 21.8

million square kilometres, a sixth of the earth, as Soviet propaganda used

proudly to announce. Just as sobering for the Wehrmacht as the size of the

Soviet Union was its climate. Its greater part was classified as within the

temperate zone (alongside smaller arctic, subarctic, and subtropical areas),

which meant that the summers, at least, were sometimes bearable for the

combatants, but then summer could also bring sweltering heat, choking dust, and

drought, or otherwise cataclysmic downpours, unending mud, and myriads of

mosquitoes. The winter, however, was uniformly horrific. It bit into all the

soldiers, regardless of whether they were deployed in Lapland or the Crimea,

and was especially difficult to endure because large parts of the Soviet Union

were still almost wild and far more sparsely inhabited than the German Reich.

In Germany, there were 131 people per square kilometre, in the Ukraine there

were 69, in Belorussia 44, and in Russia itself just 7.

In total, however, the Soviet population was enormous. In

1939, there were 167 million people; in 1941, this had grown to 194 million,

largely as a result of annexations. That in itself presented the Wehrmacht with

a grave problem: how to win a war against an enemy whose resources of manpower

were practically inexhaustible. The nature of Soviet society did, on the other

hand, also offer the German strategists one great advantage and possible

solution to the problem—it was not ethnically homogeneous, but was instead

divided between around 60 peoples and 100 smaller groups. In the First World

War, the German side had tried, not without success, to turn the Russian Empire’s

own peoples against it by adopting policies that supported national

independence movements. This was a strategy the German High Command could have

employed once again. Could have, that is, since Hitler and his followers had

quite other plans for these people. Nonetheless, particularly in the

farther-flung corners of the Soviet empire, there existed a latent readiness to

cooperate with the Germans that was not the result solely of nationalism.

Another reason was what the people had experienced of their Bolshevik rulers.

The Bolsheviks had had twenty years to make a reality of the new kind of

society they had promised, though the conditions could hardly have been more

difficult. The proletarian revolution had occurred in the country that Marxist

orthodoxy would perhaps have judged least ready for it—in a vast,

technologically underdeveloped empire that was extremely backward both socially

and politically as well as deeply marked by the Tsar, the aristocracy, the

Church, and an ancient peasant culture whose daily round was almost untouched

by the goings-on in Moscow or St Petersburg. There were additional obstacles,

first among them the inheritance of defeat in the First World War and of the

Civil War in Russia itself, one long tragedy of violence, hunger, and

deprivation that, between 1914 and 1921, had cost the lives of some 11.5

million people. Another was the ethnic fragmentation of a Soviet Union that

placed too little worth on the internationalism that formed part of its

doctrine; and, lastly, there was the long, painful coming-of-age of the

Bolsheviks themselves after Lenin’s early death (17 January 1924), a process at

the end of which stood what Lenin had warned against from his deathbed: the

dictatorship of Stalin.

It was Stalin who was truly to revolutionize the country.

Under his rule, the peasantry, the largest social group, shrank significantly,

from 72 per cent (1926) to 51 per cent (1941). Even more momentous was that

almost all peasants simultaneously lost their independence. During the programme

of enforced collectivization, they became ‘agricultural workers’ on almost

250,000 kolkhozy (collective farms) or sovkhozy (state farms). The tremendous

haste with which agricultural nationalization was driven along had a

fundamentally damaging effect on living and working conditions. In the former

breadbasket of Europe, many basic foodstuffs were rationed until 1935. The

privation was worst in the countryside, where between five and seven million

people starved to death in the early 1930s. This catastrophe was accompanied by

the deportation and execution of those whom the Soviet terror apparatus

believed to be standing in the way of Stalin’s ambitious advance towards

modernity.

The focus of his politics was the industrial sector, not the

agricultural. The latter’s collectivization was seen as merely a first step.

The old village culture was to disappear; the people were to move to the towns

and there be transformed into industrial workers, while the remaining

‘agricultural factories’ finally managed to guarantee sufficient food supplies

and even use a new surplus to finance the growth of heavy industry. That was

the grand project. Stalin wanted to make up in one decade for an economic lag

that he himself estimated at ‘fifty to a hundred years’. How to do so was

detailed in the Five Year Plans, first announced in 1929. As if it were

possible simply to command that the economy grow, Soviet society was mobilized,

made responsible for reaching the targets dictated to it, and thrown into ever

more productivity drives, which did indeed give some parts of the country a

modern appearance. New industrial concerns and factory towns appeared, along

with blast furnaces, canals, tractors, and vast water reservoirs. One statistic

after another celebrated the ‘construction of socialism’, and, even if that was

still limited to a single country, victory over capitalism was declared

nonetheless. Much of that was unfounded propaganda, but not all, as Soviet

gross domestic product increased by 50 per cent between 1928 and 1940, and a

basis was laid for the growth of heavy industry. Not only did the economy

change; there emerged a new breed of proletariatians, young and mobile, with a

high ratio of women and far more open to the slogans of socialism than their

peasant parents had been. Between 1926 and 1937, the proportion of industrial

workers in Soviet society was multiplied tenfold, from 3 per cent to 31 per

cent. It was a huge effort, almost ex nihilo, and it allowed the Soviet Union

gradually to become an industrial and then a military power, as well as turning

it into a country that corresponded at least in outline to the Bolshevik

conception of what society ought to be. It was enough to make many believe in

the utopian vision of a new, equitable world to come. Despite all the bungling

and the profligacy, the economic trend was directed very distinctly upwards.

But the price was high. This huge effort to which almost

everything was sacrificed—capital, workers, resources—came at the cost of

sustainability, quality, and individual consumer goods, as well as doing

unprecedented structural damage to the Soviet economy. Even more serious was

the abyss of violence in which the socio-economic revolution was forced

through. There is no question that the Bolshevik regime had been accompanied by

violence from the first and that its use was not a new phenomenon. During the

Civil War, the Red Terror had already claimed 280,000 victims. Its conception

of the enemy had even then been a broad church: spies, counter-revolutionaries,

saboteurs, the bourgeoisie, ‘enemies of the people’, priests, kulaks, and all

members of all non-Bolshevik parties or national autonomy movements.

But it was under Stalin that the politics of repression,

murder, and ‘liquidation’ reached their height. Between five and seven million

people lost their lives during the enforced collectivization of agriculture at

the start of the 1930s, particularly in the Ukraine, along the Don and Kuban

rivers, an area from around which a further 1.8 million people were deported. This

was followed after 1935 by the deportation of individual ethnic groups and the

continuing persecution of the kulaks, relatively affluent farmers, 273,000 of

whom were killed. Then came the Great Terror of the years 1937–8, which was

directed primarily at administrative and military officials. Some 1.5 million

people were arrested and at least 680,000 executed. Finally, 480,000 people

from the Sovietized western provinces were deported or murdered between 1939

and 1941. These were undoubtedly extreme examples of Stalin’s governance, but a

permanent war against his own society was an essential characteristic of the

regime. He demanded, this was the crux, that society be the way he imagined it,

a way that in reality it never was. The consequence was an uninterrupted series

of inspections, show trials, arrests, deportations, and ‘purges’ of his own

administration, accompanied by the construction of a gigantic network of prison

camps, the notorious Gulag Archipelago. The Gulag became a dark parallel

society living in the shadow of the Bolshevik upswing that Stalin announced in

1935 had made life ‘better’ and ‘happier’. For the eighteen million people who

passed through the Gulag under his dictatorship, it was certainly neither; as

early as 1941, two million had succumbed to the inhuman conditions. Taking

these into account, there is a large body of evidence to suggest that, between

1927 and 1941, Stalin’s politics claimed the lives of some ten million people.

At the outbreak of war, Stalinist Russia thus had far more

on its conscience than Nazi Germany. The latter would, however, do much

throughout the rest of its short existence to make up the deficit. To

understand this as a reaction to Soviet atrocities would be fundamentally

misguided. The criminal character of both regimes was inherent in their

ideologies, their mentalities, and also in their organizations; they were two

separate and self-contained systems with their own sets of historical and

political preconditions. In Poland alone, the German occupiers had shot more

than 60,000 people by the end of 1939. That these two totalitarian regimes

would then reciprocally influence and radicalize each other in their fight to

the death was almost an inevitability. However, their actions were still

generally determined by what they had brought with them into the war:

ideologies that treated such principles as tolerance, individuality, and the

rule of law with nothing but contempt.

The defenders

The Soviet Armed Forces also found themselves in a period of

upheaval. By the early 1940s, little remained of their origins in the dramatic

years of the Bolshevik Revolution and the Civil War: the political symbolism,

perhaps, and the system of having commissars shadow the officers, as well as a

few commanders whose careers had begun in 1917. But it was precisely in the

officer corps that it was evident how much the Red Army had changed. The

officers had been among the first victims of the purges that took place between

1937 and 1940. Of the 5 Marshals of the Soviet Union, 3 ‘disappeared’, along

with 29 of the thirty army commanders and commissars, and 110 of the 195

division commanders. In total, of the 899 highest-ranking officers, 643 were

persecuted and 583 killed. In all, about 100,000 ordinary soldiers were subject

to some form of repression. This was no coincidence. Although the Workers’ and

Peasants’ Red Army, as it was officially called, had been at the disposal of a

dictatorship since its inception, it had still been allowed a certain

professional autonomy. Now, however, the guiding mentality made an abrupt

about-turn. Now it was important above all to toe the political line and that

meant total orientation on the vozhd, Stalin.

That was not the only change. What is also striking about

the period before the war is the Soviet Armed Forces’ exponential growth. From

529,000 men (1924) to more than 1.3 million (1935–6), it had reached a total of

5.3 million men by 1941, around half of whom were stationed on the western

border. Another twelve million men were available as reserves. This explosive

expansion was accompanied by an acceleration of material provision in which, it

has to be said, sheer volume of equipment was prized above its efficacy.

Nonetheless, at the outbreak of war, the Red Army had an enormous arsenal at

its disposal: 23,000 tanks, more than 115,900 heavy guns and mortars, and

13,300 usable aeroplanes. There is no doubt that it had become one of the most

powerful armies in the world, even if the Soviet leadership continued to make

the mistake of confusing quantity with quality. But at that point—and this was

the salient fact—they did not really expect to be fighting a major war, not

least because the record of the few Soviet deployments before summer 1941 was

decidedly patchy. In the small Manchurian border disputes, they had gained the

upper hand against the Japanese (1938–9) and just about managed to succeed in

conquering the half of Poland allocated them, but the war against Finland had

very nearly ended in fiasco. This, too, seemed to indicate that the Red Army

could not be considered battle ready before summer 1942 at the earliest.

The German invasion struck them with a terrible shock. The

dominant sentiment of the Soviet defenders in the first months of the war can

have been nothing but fear: fear of the apparently invincible supremacy of the

German invaders; fear of control by the political cadres, who initially thought

it would be possible to manage an army like a party organization; fear of the

officers, who callously threw away the lives of their troops; fear of the

indolence in the supply lines that meant what was really needed did not reach

the front; and, not least, fear of death, which soon became terribly familiar

to the Soviet troops. More than 3.5 million of them did not survive the first

year of the war. One officer of the German High Command wrote in his diary that

‘the Russians sacrifice their people and they sacrifice themselves in a way

that Western Europeans can hardly imagine’.

And yet, the Red Army was collectively able to bring the

Wehrmacht to a halt. There were many reasons for that: the Soviet Union’s

almost inexhaustible reserves, the steadily improving quality of their

armaments from autumn 1941, the knowledge that they were fighting a just cause,

and, finally, the lessons learned in the hard school of war in which the

soldiers of the Red Army had no choice but to enrol. Although their losses were

horrendous, although the Red Army lost the majority of its heavy weaponry in

the first months of the war, a new army emerged that was vastly superior, in

both quantity and quality, to that of 1941. A proud Soviet political officer

wrote of the army’s operations in 1943 that ‘even the Germans in 1941 were

never as good as this’. Two years earlier, he had ended up among the partisans

after the destruction of his unit and had lived to see regular Soviet divisions

fight their way through to him and his comrades.

At that moment, in autumn 1943, the Soviet Armed Forces

consisted of 13.2 million people in total, 5.5 million of them fighting on what

for the Soviet Union was the Western Front. By the end of the war, the Soviet

Union had mobilized 30.6 million soldiers, 820,000 of them women. Their

equipment, too, changed beyond recognition. The Red Army became more mobile,

largely because of the tens of thousands of vehicles that arrived from the USA

and Great Britain, but, most important of all, it learned to hit harder. The

most feared Soviet weapons of the Second World War were the T-34 tank, the

heavy guns, the PPSh-41 submachine gun with its distinctive drum magazine, the

Katyusha rocket launcher, the mortars, and an artillery that grew into a

rolling thunder of regiments, divisions, and even whole artillery armies the

like of which the world had never seen. Stalin thought of them as embodying the

god of war. Finally, there was the air force; in 1941, its machines were swept

from the sky by their German enemies or destroyed while still on the ground. At

the beginning of 1943, the tide turned, and aerial dominance became the

privilege of the Soviets. That was not simply because of their new machines,

which were stronger and more modern. ‘Against ten of us there were often three

hundred Russians,’ remembered one German fighter pilot. ‘You were just as

likely to have a mid-air collision as to be shot down.’

The fatal blow, however, was struck on the ground. By that

point, the Red Army’s soldiers were professional, confident, and highly

motivated. ‘I can be proud’, wrote a lieutenant in October 1942, ‘that the

battlefield is covered in Krauts I’ve personally killed and counted off …’.

What came to matter in the army was no longer class background and political

loyalty, but ability and action. The Party and the state also learned to make

use of the deeply rooted patriotism that had lain dormant in Soviet society.

They created Guards Regiments, uniforms reminiscent of the old Russia, and an

elaborate system of honours. There was little talk of internationalism in this

hour of need. Confronted with the nature of the German occupation, most of the

soldiers must have been entirely convinced of the reason for their

deployment—most, but not all, because Soviet society always remained

politically and ethnically far more heterogeneous than its leadership would

have cared to admit. A sophisticated surveillance apparatus, the system of

assigning certain battalions for punishment or using them to prevent others

retreating, as well as summary executions, all remained part of the military

everyday, along with a High Command that used the people entrusted to it with a

shocking wastefulness. Even at the beginning of 1945, one in sixteen Red Army

soldiers captured by the Wehrmacht was a deserter. This ambivalence—boundless

devotion and enthusiasm, but also indoctrination, control, terror, and an

unprecedented profligacy with human life—all these characterized the situation

of the Soviet military. The sole aim was to win the war—regardless of the price

that would be paid, above all, by its soldiers.

The war from above: overview

There are few subjects as historiographically difficult and

challenging as the description of war. That applies particularly to its

epicentre, to the actual fighting. There are a great many people involved, as

well as enormous, complex organizations; there is a permanent alternation

between high drama and phases of crushing tedium; there are the intensely

emotive subjects of death, defeat, and blame; and there are necessarily two

contrary perspectives that often seem incommensurable. In the case of a war as

large and also as extreme as the German–Soviet one, merely sketching an

overview of the military operations presents a challenge. In 1942, these took

place on a front that stretched 3,000 kilometres through the Soviet Union. Of

the innumerable engagements that were played out, many have by now been

entirely forgotten, even though tens or even hundreds of thousands of soldiers

were involved.

In the midst of this apparent chaos, however, it is possible

to make out certain patterns. One is determined by the seasons. The great

German offensives always took place in summer, those of the Red Army initially

only in winter. And there is something else that catches the historian’s eye:

German offensive capabilities shrank from year to year. Whereas the Wehrmacht attacked

along the whole length of the front in 1941, in 1942 it did so with only one

Army Group; in 1943, with two smaller armies, and, finally, in summer 1944,

none of the German forces in the East was able to advance from its position.

Now that its opponent had seized the initiative during the Germans’ favoured

season, it could no longer be recovered. Casting an eye over the Soviet

operations, on the other hand, rapidly makes clear the extent to which the war

was a learning process for the Red Army, on all levels of military

thinking—tactically, strategically, and operationally. It continued to make

dreadful errors right until the end, and those errors contributed as much as

anything to the horrendous losses that it suffered.

A second organizing idea in this tremendous military

struggle is that of territory. War is always partly a geographical phenomenon.

Territory, in a sense, provides the parameters; it gives an unmistakable

indication of the two opponents’ successes or failures. This is particularly true

of a war such as that in the Soviet Union. Of course, it is often overlooked

that this conflict was not only a war of manœuvre. Long stretches of the front

fought a war of attrition that outwardly at least was reminiscent of the First

World War. But, even then, the military events were not confined to the

comparatively narrow band of two parallel front lines. In a contest

characterized by limitless violence, it was inevitable that the hinterland,

too, would become a war zone. Nevertheless, the war was decided by what

happened at the front, along the main lines of battle. Everything else was

dependent on that. That is why an operational history remains indispensable to

understanding the course of the war. The thin line of the front formed the axis

around which all else turned.

1941: the German invasion

Bright and early on 22 June 1941, a sunny Sunday morning,

the Wehrmacht crossed the border. There had not been a declaration of war; it

was a surprise attack. That was one of the key reasons why it seemed that the

German troops would soon add the Soviet Union to their list of conquests.

Stalin had repeatedly been warned about the build-up to Operation Barbarossa

but had consistently refused to put the Red Army into defensive readiness.

Instead, his High Command had concentrated the majority of its forces on the

border, because Soviet doctrine stipulated that, in the event of an attack, the

army was immediately to carry the war onto enemy soil. Nonetheless, or in fact

precisely for that reason, the four German panzer groups quickly succeeded in

breaking through the Soviet positions, forming the first ‘cauldrons’,

encirclements of enemy armies, and managed to advance 400 kilometres into

Soviet territory within a single week. For the German infantry armies following

along behind in that hot, dusty summer, that meant: marching, more marching and

then ‘clearing’ one cauldron after another. Soviet prisoners were soon being

counted in the hundreds of thousands.

The German leadership was triumphant. Before the outbreak of

war, it had had a nagging fear that the enemy units would—as in 1812—fall back

into their country’s interior and refuse to give battle. That had obviously not

come to pass. On the contrary, the toughness of Soviet resistance seemed to

confirm the assumptions on which the German strategy was built. On 28 June,

German troops conquered Minsk, the capital of Belorussia; on 15 July, they were

already at the gates of Smolensk. In three weeks, the distance between Army

Group Centre and Moscow had thus shrunk from over 1,000 to around 350

kilometres. ‘In our mind’s eye, we can already see the towers of the Kremlin,’

exulted the members of one German infantry regiment. Even the head of the

German General Staff, Franz Halder, believed at the start of July that ‘the campaign

against Russia will be won within a fortnight’. He was not the only one of this

opinion. In Great Britain and the USA, the Soviet military had already been

written off. One British general wrote, ‘I fear they will be herded together

like cattle.’

But this belief ran counter to all military experience.

According to the old rule of thumb, it is only with a three-to-one advantage

that victory is assured. Since in this case the defenders in fact retained

numerical superiority and continued on the whole (though not always) to fight

hard and bitterly, the German troops, pushing ever farther into the unending

emptiness of the steppe, began to win their victories on the point of

exhaustion. This could be seen in their losses, which were particularly dire in

the battles to break through Soviet lines as a prelude to encirclement, and it

could be seen in what was happening to their equipment. Before long, more

German vehicles were being lost to dust, mud, and the catastrophic roads than

to the enemy. In August 1941, an officer in a German Infantry Division noted

that the East was now beginning ‘to show its true face’. The German armies were

not prepared for what they now encountered. Reserves of everything were short,

and the supplies of fuel, rations, ammunition, and spare parts, to say nothing

of vehicles proper, began to run out after only the first weeks. A decisive

battle no longer seemed probable, and the Germans began to lose their taste for

the word Blitzkrieg, the lightning war. When Chief of Staff Halder was forced

to confess, on 11 August, that ‘we have underestimated the Russian colossus’,

the consternation among the leadership was already palpable. Even then, they

were no longer really sure what to do next.

What followed were heated discussions in the Führer HQ about

the future focal points of the German offensive. This question, like so much

else, had initially been left unresolved. While Hitler wanted above all to

occupy the Soviet centres of industry and raw material, and thus favoured the

two wings of the three more-or-less equally strong Army Groups—that is, ‘North’

and ‘South’—it was clear to his military advisers that that could not happen

before a decisive victory had been won in the field. Only an attack on Moscow,

on the centre of the enormous Soviet empire, seemed likely to provide it. There

is no doubt that the loss of the capital would have been a powerful blow to the

Soviet enemy. However, it does also seem questionable whether a war of this

scale and kind could have been ended with a single ‘decisive’ manœuvre. It was

almost as though the German military, in near desperation, were clutching at

this one tangible goal merely so as to make sense of an increasingly

unmanageable campaign. And not only that. For the exhausted and disillusioned soldiers

who were already ‘thoroughly sick of Russia’—as one soldier wrote as early as

August—Moscow presented a large and apparently convincing target. Its name was

a promise of victory, and even perhaps of a speedy end to the conflict.

Hitler’s ability to assert himself over his advisers in the

making of these plans demonstrates the extent to which he by now also dominated

operational strategy. When he, in August, switched the focal point of the

German offensive from Moscow to the south-east, it resulted in another great

success for the Wehrmacht—at least on the face of things. In a cauldron outside

Kiev, a further 665,000 Red Army troops had laid down their arms by the end of

September. It was one of the Red Army’s largest and most comprehensive defeats.

But neither that nor the conquest of the Ukrainian capital provided a military

turning point. In September, the increasingly perplexed Führer therefore

decided to attack Moscow after all, even though the conditions had altered and

it was now far later in the year.

It was only on 2 October 1941 that the Eastern Army was in a

position to launch its supposedly final onslaught. Seventy-eight divisions,

nearly two million men, had been gathered in the centre for Operation Typhoon.

Chief of Staff Halder wrote that it was finally time to ‘break the back’ of the

Red Army. And, indeed, by 20 October the Soviet side had lost 673,000 soldiers

and almost 1,300 tanks in the twin battles of Vyazma and Bryansk. By December,

individual German units had managed to fight their way to within 30 kilometres

of the Soviet capital. But now it was also becoming unmistakable how severely

the German Eastern Army had been depleted by the offensive. The change of

weather in autumn had already made things difficult: rain and then snow transformed

the Russian roads into a grey, bottomless morass into which whole armies sank.

By mid-October, the entire Army Group Centre was stuck fast ‘in mud and

sludge’, as their Commander in Chief, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, noted with

chagrin.

In November came winter, bringing catastrophe in its wake.

Since the High Command had organized winter provisions for only a small

occupying army, most of the German soldiers continued to fight in their

tattered summer uniforms. One of them described their everyday existence as

follows: ‘The men wake up at around three or four in the morning and get ready

to move out, usually without washing, because the water is too far away and

there’s no time and no light. The marching then goes on all day until late on,

again in the dark, often at nine or ten o’clock, when the men reach their

quarters and have to care for the horses and set up the stalls before they have

their mess at the field kitchen and then lie down to sleep.’ Nevertheless, the

soldiers were driven ever further east by their commanders—in the putative hope

that the Soviet enemy had already been essentially beaten and that all that was

now required was a last, decisive ‘battle of annihilation’.

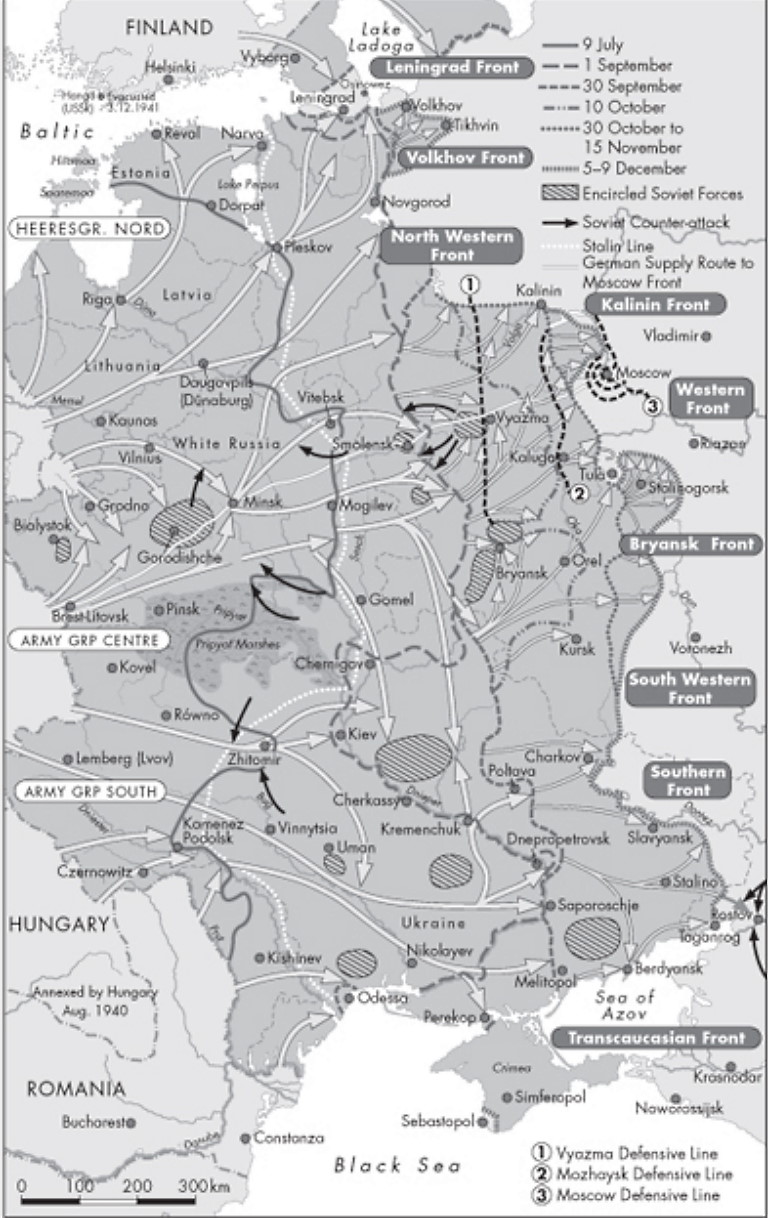

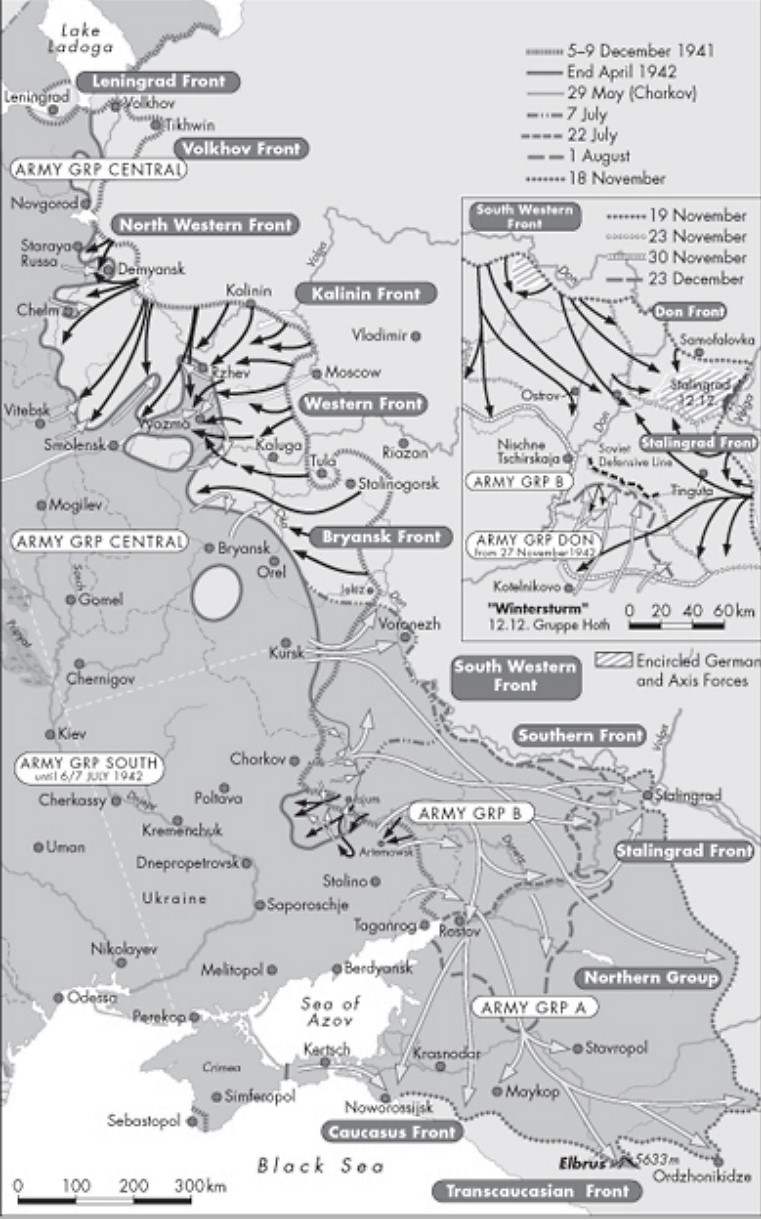

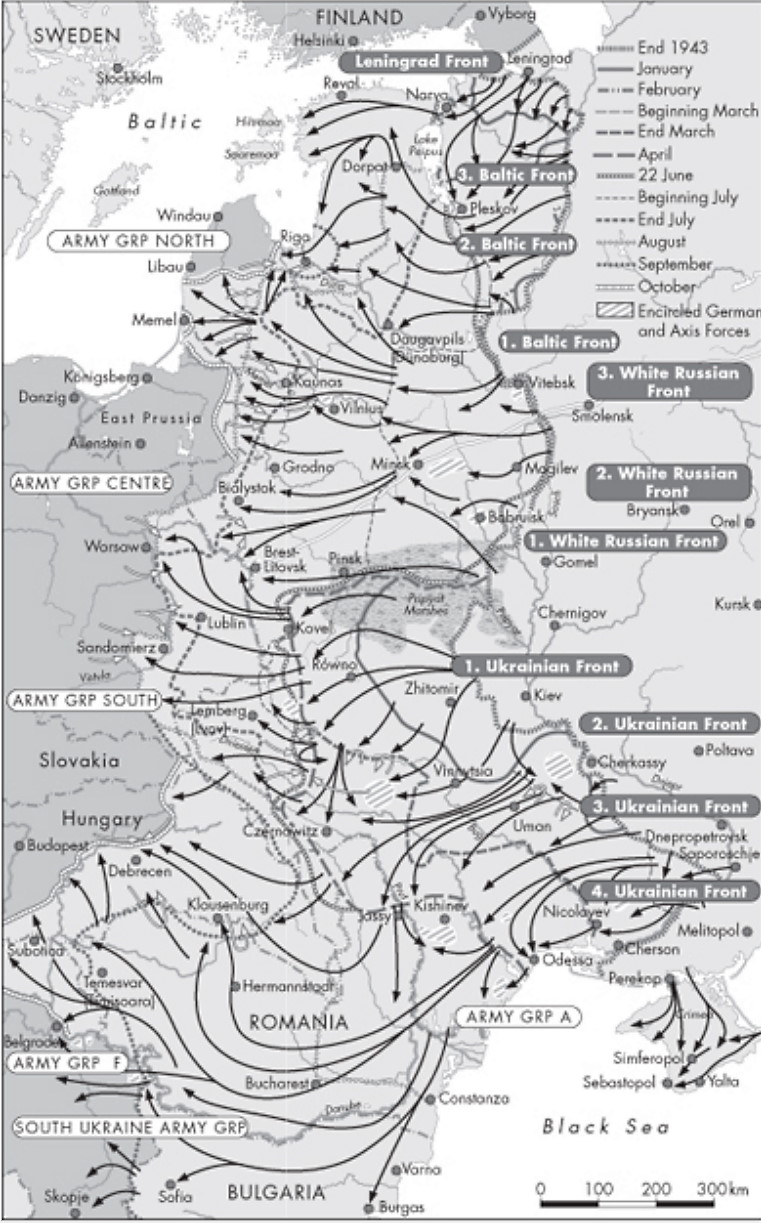

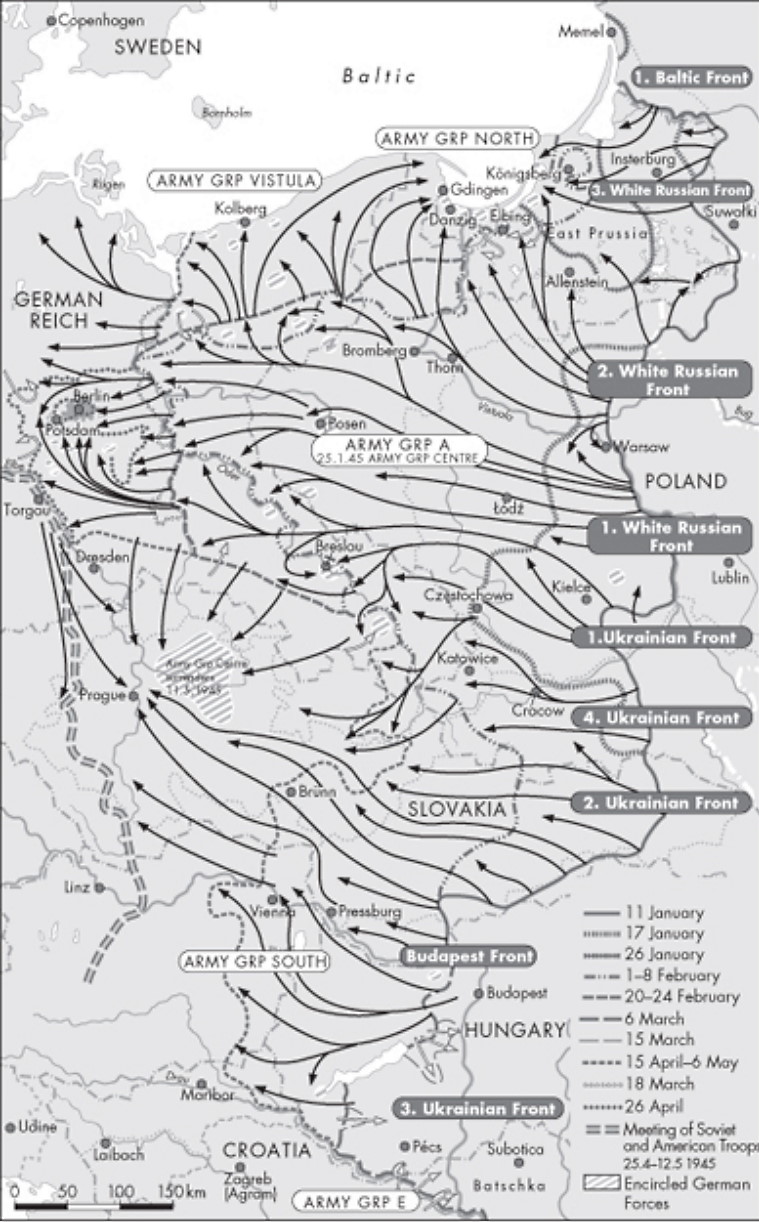

Map: The Eastern Front in 1941

A battle of this type did indeed begin on the 5–6 December

1941, albeit moving in the other direction. German intelligence had completely

failed to notice that the Red Army had brought up new troop reserves after

realizing, in November, that Japan would attack the USA rather than the USSR.

The Soviet offensive struck the German units, already thinned out and dead

tired, in the moment of greatest weakness, that of a stalled offensive. The

consequences were as one would expect. In temperatures that fell to −52 °C,

Army Group Centre was propelled a distance of between 150 and 300 kilometres to

the west. Nothing was as strongly reminiscent of Napoleon’s Russian campaign,

the military disaster par excellence, as the image of German columns struggling

westwards through snow and ice. ‘For days on end, the wind whipped up the fine,

powdery snow and drove it into our eyes and faces, so that one had the feeling

of having stumbled into a rain of needles,’ wrote a German military chaplain

about the retreat of his division. ‘Since the storms came mainly from the east,

the enemy usually had them at his back. It was easy for him to move his troops

forward under the cover of snow clouds so that they would be noticed only at

the last moment.’ By the end, in his unit ‘approximately 70 per cent of the

troops had frostbite, partly third degree’. Their commanders’ prognosis was

equally bleak: ‘Fighting capability of the troops is zero, as completely

exhausted.’

This was no ‘straightening of the front’, as was claimed by

the Reich’s propagandists. The whole German Eastern Front was in danger of

collapse. That it did not come to that was not only because of the cohesion,

skill, and toughness of troops who knew that they were fighting for their

lives. It was also due to the grave errors still being made by the Stavka, the

Soviet High Command. It did not manage to gather its forces and concentrate

them on a small number of crucial targets. From February onwards, the Soviet

attacks were increasingly ragged and ever more Red Army troops died pointlessly

in front of the German lines. It was not rare to find that battles were reduced

to a ‘fight for an oven’, a scrap over the few villages that remained intact in

the desert of snow. When the fronts then sank into the bottomless mud of spring

1942, both sides were equally glad of the break. It lasted long enough for the

German front, which now ran straight across Russia and the Ukraine, from the

area around Leningrad to the Black Sea, to be at least partly consolidated.

That, however, was the only gain made. Hitler’s strategy, the plan of a

worldwide blitzkrieg, had definitively failed, so definitively that the German

Reich had almost gone under—as early as that, in winter 1941–2. The prospects

for the future were not much brighter. Instead of winning itself strategic

freedom of action, the German High Command now found itself having to manage a

war on two fronts at a time when it was already evident how overextended its

forces were. ‘We have been punished for overestimating our strength and for our

hubris,’ read the assessment of an officer in the German General Staff in

December 1941. ‘If only we can distil some lessons from the events of the last

months.’

1942: the second German offensive

Learning lessons was something Hitler would not do. He would

not be wrested from his principle of escalating the odds in the face of risk.

After the Eastern Army had, by 1942, suffered losses of over a million killed,

wounded, and missing, an attack along the length of the front was no longer

possible. Instead, there would be an attack along one section in the south. All

reserves and all supplies were scratched together; where they were

insufficient, the Germans’ allies had to make up the shortfall. Time was short

because, since 11 December 1941, the German Reich had also found itself at war

with the USA. If there was to be any chance at all for the Reich, Hitler

thought it would lie in the Caucasus. Before American armament production could

start to run at full capacity, the German Reich would annex the military

potential of the Soviet Union. In order to do so, the summer offensive was

planned in two phases: it would first advance onto the Volga at Stalingrad,

then—after building up an east-facing front—wheel around towards the Caucasus

so as to take possession of the Soviet oilfields. Without them, the Soviet

Union—so hoped the Germans—would collapse.

The German offensive began on 28 June 1942. After a number

of preliminary battles—around Kharkov, Izium, and on the Crimean Peninsula,

which the Germans had occupied by 1 July—four German armies, supported by

Hungarian, Romanian, and Italian divisions, initiated Operation Blue. Again,

the attackers made rapid territorial gains. But now, and increasingly often,

their offensives ran on and on into an enormous void, because Stalin, after

long hesitation, had eventually given his commanders permission for a tactical

withdrawal. Given the paltry numbers of Soviet prisoners taken, Field Marshal

von Bock remarked that there was danger of having ‘struck at thin air’. Hitler

was not receptive to such doubts and permitted less and less outside

involvement in his operational leadership. Believing that the enemy had now

been beaten at last, he split the German offensive and directed the armies

simultaneously, rather than one after the other, towards Stalingrad and the

Caucasus. At first, this fateful decision could hardly slow the pace of the

German advance. Churning up thick clouds of dust, the troops marched ever

further east across the shadowless steppe, crossing the border into Asia at the

end of July and reaching the burning, destroyed refineries of Maykop at the

start of August. On the 22nd of that month, German alpine troops raised the

Reich’s war flag above the Elbrus, the highest mountain in the Caucasus. Days

later, the Sixth Army’s first reconnaissance units were standing on the banks

of the Volga, north of Stalingrad. Never before had the Germans ruled over such

an enormous territory.

And then everything stopped. Now, if not before, the German

leadership had indubitably expended or worn out the last of its resources; one

German major wrote that his troops had already been ‘stripped of all but their

shirts’. The tormenting question of the previous weeks, of how long the Soviet

Union would hold up against this renewed onslaught, began to be answered slowly

and almost imperceptibly. At first the Germans noticed only that the battles in

the ancient forests of the Caucasus moraine and in the stone deserts of

Stalingrad were beginning to bite. The battle on the Volga, in particular,

developed into a duel between the dictators, a matter of prestige that sucked

in more and more troops. On 28 July, Stalin gave his famous order: ‘Not one

step back!’ In a public speech on 8 November, Hitler replied that the battle

for Stalingrad had basically already been decided. But that victory could not

be talked into existence. The German intelligence service again failed

catastrophically. On 19 and 20 November 1942, two Soviet attacks broke through

the brittle and overstretched German lines in the icy steppe to the north and

south of Stalingrad. Those posts were manned above all by the Germans’ allies;

badly led, miserably equipped, and simply unequal to the task, they had little

to set against the advancing Soviet tank wedges. The inevitable happened. By 22

November, the German Sixth Army was locked in; 200,000 men sat in the trap, in

an enormous ruin surrounded by a frozen waste and by seven Soviet armies;

25,000 German soldiers were flown out of the encirclement, 110,000 went into

Soviet captivity, only 5,000 returned to Germany. ‘This is the last letter that

I’ll be able to send you,’ wrote one German corporal. ‘We’ve just been unlucky

this time. If these lines are at home, then your son isn’t here any more, I

mean, on this earth …’. On 2 February 1943, the last German units capitulated.

‘Temperature thirty-one degrees below, fog and red haze over Stalingrad.

Weather station signing off. Regards to the homeland,’ was the last German

radio signal the Wehrmacht received from Stalingrad.

Despite all the drama, despite all the consequences, this

was not the turn of the tide for the Second World War as a whole. The overall

reversal of fortunes, which had already begun in the winter of 1941–2 and which

can be tracked particularly closely on the Eastern Front, was, rather, a

dynamic process. The Soviet odds of victory shortened as the German odds

lengthened. Nevertheless, many contemporaries felt that the battle for

Stalingrad was the turning point of the war, because the slow, torturous, and

ultimately pointless extinction of the entire Sixth Army took on a tremendously

powerful symbolic value. According to a secret service report, the Germans were

‘profoundly disturbed’. Germany’s partners began to reconsider their role, and

hope grew for the Allies. At that point, the Greater German Reich still held

sway over almost all of Europe, at least on the map. The northern and central

sections of the Eastern Front, where a grinding but inconclusive war of

attrition was being waged, still seemed comparatively secure. But in the south

there now yawned an enormous gap that threatened to widen ever further, and nor

was that the only crack in ‘Fortress Europe’. Around the Mediterranean, the

Allies had succeeded in doing precisely what the Germans had tried to prevent:

they had launched a Western offensive. The British had won at El Alamein (23

October to 4 November 1942), and Allied troops had landed in Morocco and

Algeria (7–8 November 1942). All at once, the collapse of the German empire

seemed close at hand.

Map: The Eastern Front in 1942

The war from below: soldiers and civilians

Every war demands blood, sweat, and tears from its

participants. To bear that in mind is anything but banal—it is, if nothing

else, a moral necessity. Moreover, that reflection gives an idea of the

conditions under which war is actually fought. Nevertheless, like every

military undertaking, the German–Soviet War had its own unique

characteristics—its extreme radicalization, for instance, which was something

felt first by those at the bottom of the military pyramid.

Given the extent to which the war was shaped by wider

factors such as the landscape and the weather, it was by no means rare for the

experiences of the German troops to resemble those of the Soviets. Their

letters, diaries, and memoirs habitually circle around a few central subjects:

the unimaginable strain of war, but also the anecdotes derived from it; the

exhilaration of battle, of victory, and adventure; the deeply felt comradeship

that allowed them to endure more than seems possible; the humiliations at the

hands of the military apparatus, but also its protective function; the killing

and being killed; the loss of close friends and the resultant guilt; and

finally apathy, despair, and naked fear. In these conditions, the soldier’s

life was concentrated for long stretches of time solely on surviving the day or

on the microcosm of his unit. Everything else seemed secondary by comparison.

For that reason if no other, soldiers had no sense of ‘the big picture’ and

knew little or nothing about what their Commanders-in-Chief really wanted. ‘We

only see our little section of the front,’ wrote a lance-corporal in January

1943, ‘and don’t know what’s being planned on a larger scale’.

That is not to say that the deployment of these soldiers was

without political implications or that they were indifferent to the military,

political, and ideological superstructure of the war. On both sides, it was not

unusual to fight with an extraordinary, almost religious devotion, not least

because both believed themselves to have right on their side. On one side: the propaganda

lie of a preventative strike; on the other: an appeal for unconditional

dedication in the defence of the homeland. A Soviet recruit in January 1943

revealed that he had ‘only a single thought: to become a marksman and destroy

the fascists as quickly as possible, so that we can live happy and free again

and see our dear mothers, sisters and girlfriends’. There is what reads almost

like a direct response in a letter sent home from the Eastern Front in November

1944 by a young German Red Cross nurse: the war would be lost ‘only in the

moment in which we lay down our weapons. As long as a corner of Germany is

still free of the enemy, I will not believe that history has sentenced my

people to death.’

But nothing could be less accurate than explaining the

position the soldiers were in and the actions they took solely with regard to

their personal convictions. These were overwhelmingly determined by something

else. Dirty, obedient, and overstrained, the troops felt hopelessly at the

mercy of the war and of a vast system of labour division that was built on

orders and submission, for which nothing counted but military rationale. It is

unquestionable that individuals also had a degree of personal responsibility

within this system. Sometimes this responsibility was large—as a result of a

situation, of a mission, or simply because of their military rank. But it was

far more common that individuals had little opportunity to voice their opinions

or to take decisions. Most soldiers were in subaltern posts or performing

subaltern functions, and their responsibility for what occurred remained

correspondingly limited. It was this context that shaped their thinking and

their actions more than anything else.

Contrary to widely held opinion, neither fighting nor war

crimes were constant on the Eastern Front. The soldiers’ everyday life was

characterized by comparatively uneventful experiences: endless transports or

marches; digging into positions or searching for something to eat, for

somewhere to rest, or for a little privacy; keeping watch at distant posts;

receiving orders; going on trips to the field hospital or even just waiting

around for something to happen. This was then repeatedly interrupted by phases

of drama and intensity in which much could be decided in the briefest

time—one’s own fate, that of the enemy, and also that of the civilian

population. In fact, the military events proper were relatively unlikely to

result in war crimes. Although battle was dynamic and necessarily characterized

by both contact with the Soviets and a destabilizing unpredictability that

could potentially lead to war crimes, these operations were nevertheless

focused on engagement with a military enemy, and so the violence at least

possessed a certain symmetry and equality. During periods of fighting, the

individual soldiers were also borne by forces beyond their control. The

situation was quite different once the battle had moved on; it was then that

individual responsibility came to the fore. It is no coincidence that most of

the crimes committed during the war took place far behind the front line.

These were not the only similarities in the daily existences

of the German Landsers and the Red Army troops. Both learnt a new toughness and

a huge capacity for suffering, another reason why they gave so little ground in

battle. Both armies also bore an enormous weight of expectation from their

supreme political and military commanders, whose all-too-often amateurish

leadership did precious little to offset. Typical of the Wehrmacht as of the Red

Army was a close consensus between the front and homeland, as was a fear of the

enemy that made it impossible for many soldiers to imagine ‘opting out’ of the

war. Indeed, desertion or captivity brought with them the grave dangers of

being caught between two totalitarian dictatorships. Prisoners of war often

ended up in places with a striking similarity to concentration or even death

camps.

Of course, there were differences as well as similarities

between the two sets of troops. Their behaviour bears the imprint of the

different systems under which they operated. One cause of the Germans’ initial

military success was surely the fact that the German soldiers, at least when it

came to military tasks, were accorded a relatively high degree of autonomy. The

bleaker the outlook became, however, the more extensive became Hitler’s mania

for control. In the Red Army, an opposite development can be traced, eventually

resulting in what was almost an emancipation of the troops. Almost, because, on

the whole, the Soviet Union handled its soldiers with an unimaginable

indifference to human life; no army ‘liquidated’ so many of its own troops as

the Red Army. When it comes to the war crimes of the Wehrmacht and the Red

Army, there, too, the differences weigh more heavily than the undoubted

similarities, something rapidly borne out by a closer analysis of the

mentalities and reasoning behind these crimes, as well as of their scale.

Finally, the two sides’ military positions developed in opposite directions.

While the German soldiers’ lot continually worsened, the overwhelming

experience of victory ameliorated some, though certainly not all, of what their

Soviet opponents suffered.

At the end of the day, those who took part in this war did,

after all, have one thing in common: those who survived the war would never

forget it.

1943: the turn of the tide

Stalingrad, the great battle that raged as 1942 became 1943,

was a historical caesura, and for many contemporaries it was also a powerful

symbol, but one thing it was not was a mortal blow to the German military. Even

after the capitulation of the German Sixth Army (which was drawn out from 31

January to 2 February 1943), the war continued. This was because the Red Army

substantially failed to exploit the crisis on the southern flank of the German

front. In February 1943, there was suddenly a 300-kilometre-wide gap stretching

across that front, and a Soviet advance to the Black Sea seemed likely, in the

direction of Rostov. This ‘super-Stalingrad’ would have destroyed the German

Army Group Don while simultaneously cutting off Army Group A, which was still

fighting in the Caucasus. It was only a counterattack led by Field Marshal

Erich von Manstein, who took the strategic risk of allowing the Soviets to

advance beyond their lines of supply before engaging them, that prevented a

complete collapse of the southern section of the front. In truth, it was a

military miracle; the Soviet units freed up by their victory in the Battle of

Stalingrad outnumbered their German opponents by seven to one. Nevertheless, in

the battles around Dnipropetrovsk and Kharkov, the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS won

the last German victories in the East, managing to patch the front into a kind

of stability before the onset of spring brought impassable mud and the opportunity

for some rest.

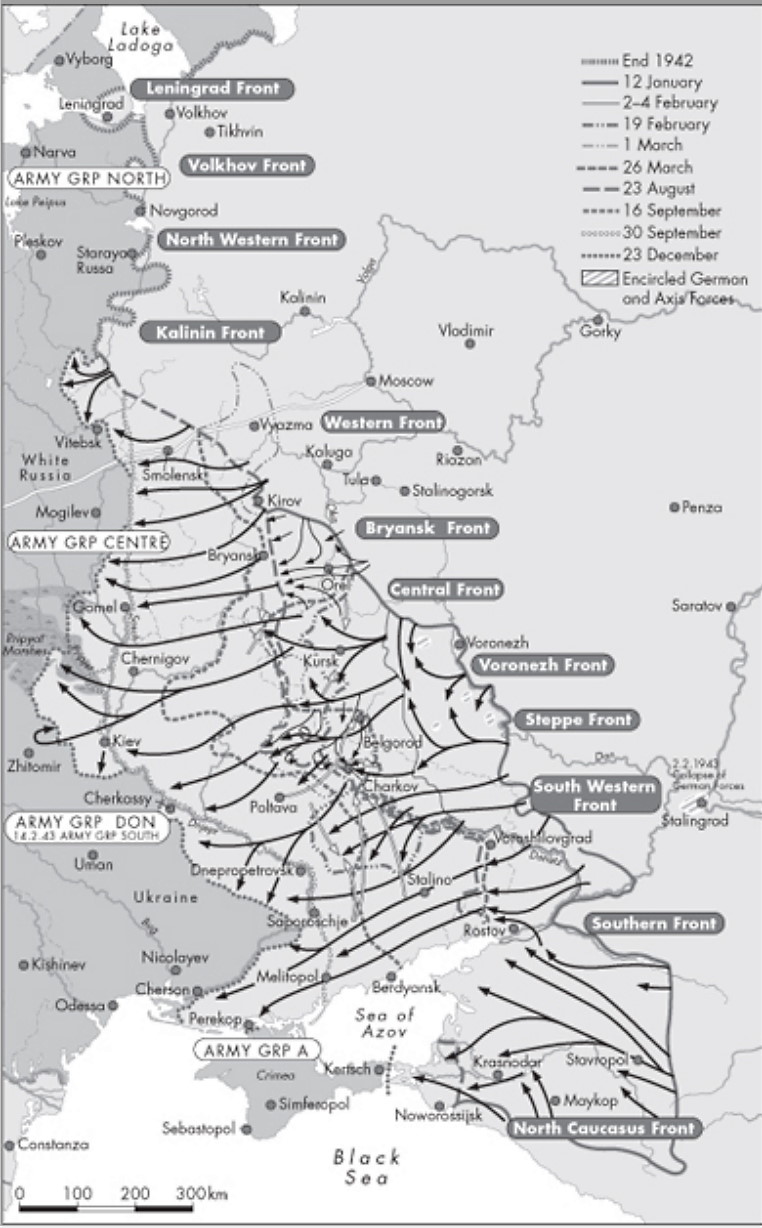

Map: The Eastern Front in 1943

The German leadership was unwilling to draw any political

conclusions from this—or even military ones. Instead of working towards a

long-term consolidation of the Eastern Front—which would have required, in

particular, a shift to mobile, defensive tactics and the building-up of

reserves—Hitler, along with a whole series of advisers, decided literally to

pulverize his own military resources in another large-scale offensive. The idea

was to use a pincer movement to cut off the outward bulge of the Soviet front

at Kursk, where it had expanded westwards into the join between the German Army

Groups Centre and South. But the problems were already starting to multiply

during preparations for Operation Citadel, for it seems likely that politics

and propaganda rather than military rationale were again the guiding

principles. Again, far too much time passed in the planning, and, worse, the

Soviet side knew all about it in advance. ‘Every valley is bursting with

artillery and infantry,’ a Soviet officer noted in his diary. On 5 July 1943,

the Germans began their assault on the well-fortified Soviet positions, but had

to call it off only eight days later, at the climax of the battle. After a

Soviet relief offensive in the Donets Basin and the Anglo-American landings in

Sicily, a German offensive on this scale was no longer possible. What remained

was something that has gone into the history books as ‘the largest ever tank

battle’: 2,900 German tanks fought 5,000 Soviet ones. ‘The air roars, the earth

shakes, you think your heart is going to shatter in your chest and tear you

open,’ was how one Red Army soldier described the experience. Kursk was a

battle of numbers, one that in its dimensions and strategies was reminiscent of

the First World War, the difference being that it was fought with Second World

War technology. The losses were accordingly high. In the eight days of their

offensive, the Germans lost 57,000 men, of whom 15,000 were killed, and their

opponents lost 70,000 men killed, missing, or taken prisoner. The losses during

the operations connected to the battle around Kursk were higher still. By the

end of August, 170,000 Germans had been killed, wounded, or gone missing in

action, and the equivalent losses on the Soviet side are also estimated in the

hundreds of thousands.

With that the German leadership had again thrown away

everything that it had managed to gather for that year: reserves, material, the

new heavy panzers, time, and—what will have been most sorely missed—the

initiative. The tank battle ended not with the German conquest of Kursk, but

with the liberation of Kharkov and Orel by the Red Army. After that, the

southern and to a certain extent also the central section of the German front

could no longer be held. In the second half of 1943, the Red Army was able to

push the Wehrmacht step by step back towards the West; daily retreats of

between 10 and 20 kilometres were no rarity. But at that point the Soviet

armies still did not manage really to engage and destroy their opponents. What

they gained in lieu were ever greater swathes of territory, including such

cities as Kiev and Smolensk, as well as a number of bridgeheads on the western

bank of the Dnieper, which the Wehrmacht had actually been supposed to use as a

defensible natural barrier. In other words, by the end of 1943, the Red Army

had not managed to drive the German occupiers out of the Soviet Union entirely,

but there could no longer be any doubt that precisely that was about to occur.

It was now only a question of when and of what would happen afterwards.

1944: the collapse of the Eastern Front

Soviet propaganda afterwards referred to 1944 as the ‘year

of ten victories’. This a somewhat contrived claim—and it has been repeatedly

criticized ever since, quite rightly. Reference to one Soviet victory in

particular should, in any case, have been enough. Operation Bagration began on

22 June 1944. In a few short days, this onslaught of more than 2.5 million

Soviet troops, supported by more than 45,000 mortars and heavy guns, 6,000

tanks, and 8,000 aeroplanes, destroyed the entire German Army Group Centre.

Consisting of 500,000 men with 3,200 heavy guns, 670 tanks, and 600 aeroplanes,

its position had been hopeless from the start. ‘Our troops storm forwards like

a mighty torrent that bursts over all barriers, sweeps away all obstacles and

washes a wide area clean of dirt and muck,’ wrote a Soviet war correspondent.

For the other side, it was one single inferno. A German artillery officer

reported that the impacts of the Soviet shells and bombs had come so close

together that explosions, smoke, and fountains of earth had prevented them from

seeing anything at all. Operation Bagration became by some distance the

heaviest of all German defeats, a defeat involving such comprehensive losses

that the memory of it was long overshadowed by that of the Battle of

Stalingrad, for the simple reason that there were so few left on the German

side to describe the destruction that Bagration had wrought. Although thousands

of isolated German troops managed, after personal odysseys sometimes lasting

several weeks, to fight their way back to their own lines, the ranks of

eyewitnesses were extremely thin, at least in Germany. The Army Group Centre

had lost 400,000 men dead or captured—that is, 32 of its 40 divisions.

The opportunities that now presented themselves to the

victorious, vastly superior Soviet armies were correspondingly extensive.

Advancing right into the heart of the German Reich and ending the war in 1944

seemed thoroughly realistic. The Soviet leadership, however, was half-hearted

in capitalizing on the situation. The Red Army instead halted on the borders of

East Prussia and on the eastern bank of the River Vistula, in the suburbs of

Warsaw. The Soviet soldiers in Poland watched, their guns lying idle, while the

Polish Home Army’s improvised uprising was miserably crushed. In August and

September 1944, the Soviet advance on the borders of the Reich came to a

complete stop. There are a number of reasons why this happened. In the case of

Warsaw, the motives for not engaging the Germans were transparently political.

The losses and efforts of the previous months were also an important factor, as

were the overextended lines of supply and communication and also the way that

discipline had sharply deteriorated among the units that had already marched

onto German soil. However, another consideration weighed far more heavily than

these: the Soviet military commanders were still extremely wary of their German

opponents. That they were not invincible had long been established, but the

Soviets had experienced again and again in the previous winters that the

Wehrmacht had an astonishing capacity for regeneration. At that point, in

summer 1944, that capacity had finally been exhausted. Nonetheless, the idea of

the Germans’ almost uncanny military abilities, the ‘Wehrmacht Myth’, was to

exert its influence one last time. That was why the Soviet leadership lacked

the courage and decisiveness to take advantage of this unprecedentedly

opportune position and strike Nazi Germany a final, fatal blow by seizing the

Reich’s almost undefended capital city. This trepidation should not diminish

the significance of the victories that the Red Army did win in 1944. That was

the year in which German occupation ended throughout the Soviet Union,

something achieved largely through Operation Bagration.

The course of the war ran parallel in the northern and

southern sections of the German–Soviet front. Between 14 and 27 January, 1.2

million Soviet soldiers broke through the German blockade to the east of

Leningrad. In that moment, the isolated metropolis’s slow martyrdom came to an

end after 880 days of encirclement, by some distance the longest siege that a

modern city has had to withstand. On the evening of 27 January, 324 guns fired

a salute over the Neva. In the following weeks, the German front was pushed

back to the area east of Estonia and Latvia. These were areas where the Red

Army was no long arriving simply as liberator. By the end of the year, the

Soviets had reoccupied the Baltic states with the exception of the western part

of Latvia, where the remaining German forces, still 500,000 men, were to hole

up as Army Group Kurland until the end of the war.

The Soviet troops gained even more ground in the south. By

as early as spring 1944, they had managed to push the collapsing German units

in the Ukraine back for more than 300 kilometres. The German troops were

repeatedly encircled and, if they were not completely destroyed, often used the

last of their strength to break out again towards the West. The events in the

Crimea took on an even more dramatic aspect. The peninsula had become a trap

for its German occupiers after Hitler had obstinately refused to withdraw them

in time. The Soviet assault that began on 8 April could not be resisted for

long. Of the 230,000 German and Romanian soldiers, 60,000 died there while the

other 150,000 were rescued in boats, under what were generally apocalyptic

conditions. This is just another example of the catastrophic consequences for the

German military of Hitler’s insistence on having operational command. After

that, the Red Army could not be stopped in the south either. Soviet troops

mounted a major assault on 20 August against Army Group Southern Ukraine and

thereafter occupied a number of territories in quick succession, first Romania,

then the eastern part of Hungary, and, by the middle of October, also Bulgaria,

which had, of course, not actually been at war with the Soviet Union. The

Balkans started to become Soviet.

Map: The Eastern Front in 1944