Battle of Seelow Heights

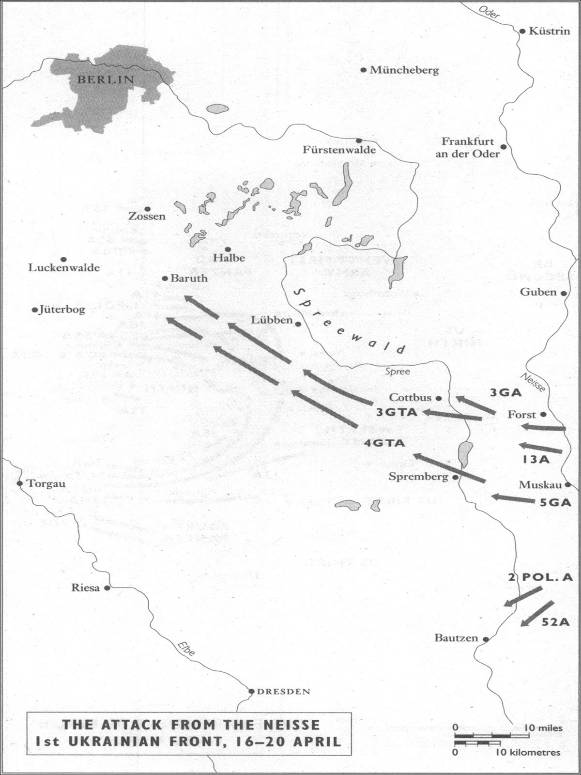

Zhukov and Konev’s forces acted as a pincer movement on Berlin. Stalin’s boundary line between the two ended at Lubben, encouraging Konev to race Zhukov for the ultimate prize of Berlin.

The delay in achieving his objectives, together with a high casualty rate, convinced Zhukov to revise his original plan and send some of his second-echelon tank units sweeping around to the north.

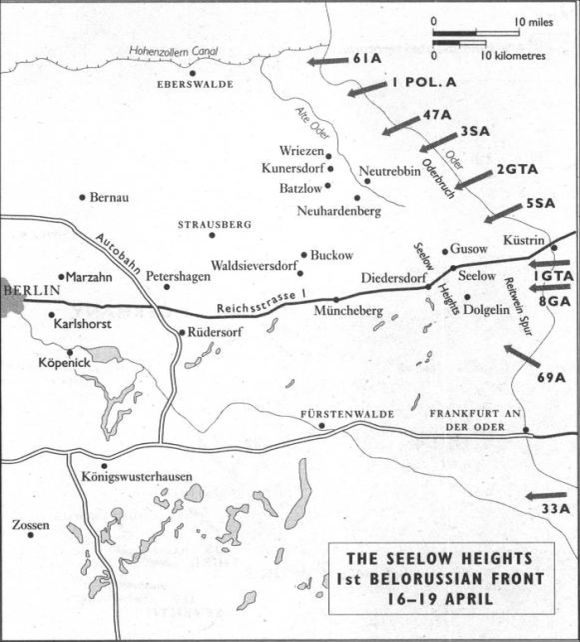

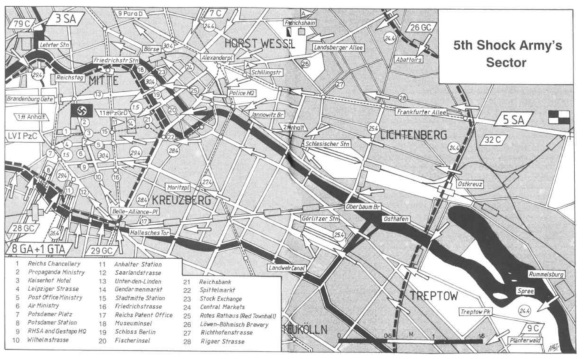

The Approach

The Soviets’ success to this point had been costly. At least 33,000 men, according to official Red Army statistics, or more than twice what the Germans had lost, had been killed so far in the operation. In addition, 743 tanks and SPGs had been destroyed; the equivalent of an entire tank army, and 25 per cent of the Soviets’ available armoured forces. In view of these losses and his Front’s two-day delay in accomplishing Stavka’s battle plan goals, and in view, too, of the fact that Konev’s First Ukrainian Front could yet reap the laurels for the conquest of Berlin, Zhukov made some revisions to his original plan. The First Guards Tank Army and Eighth Guards Army would continue to operate together as the main, frontal strike-force, driving into Berlin along Reichsstraiße 1. But Second Guards Tank Army, which had been operating in the second echelon since leaving Kustrin, would now be divided into its three main constituent corps. The Ninth Tank Corps would join 47th Army and Seventh Guards Cavalry Corps to sweep around Berlin on the north, and then come down on the far side to the Havel and block off any western approach to, or escape from, the city. Meanwhile the First Mechanised Corps and the 12th Guards Tank Corps would push into the northeastern suburbs, opening up a route for the infantry of the Third and Fifth Shock Armies. With the northern, western, and eastern suburbs cut off and occupied, and the south busy with Konev’s forces, 69th and 33rd Armies, with the reserve Third Army, would drive in and destroy what remained of the German Ninth Army. The primary target was designated as the Reichstag.

With little respite, the attack was pressed. On the morning of 20 April, as Hitler was preparing to greet his birthday guests, Allied bombers delivered as their gift a final aerial bombardment. At the same time, the long-range artillery of the Third Shock Army’s 79th Rifle Corps began the first ground bombardment of Berlin. Even as the city received this concrete announcement of the Soviets’ imminent arrival, ground troops advanced to its outskirts. The 125th Rifle Corps of the 47th Army succeeded in taking Bernau (about 15km (9 miles) to the north-east), while Third Shock and Second Guards Tank Army managed to break free of the deadly morass of the Germans’ third defensive line. Once in open country, the armour sprinted ahead of the infantry, to the north-eastern edges of the city at Ladenburg and Zepernick. Meanwhile, Fifth Shock Army, with 12th Guards Tank Corps and elements of 11th Tank Corps, finished up the neutralisation of the third defensive line, and prepared to take Strausberg. Around 2000 hours on the evening of the 20th, Zhukov issued a radiogram order to the commander of First Guards Tank Army, Marshal M.E. Katukov:

‘Katukov, Popiel. [Katukov’s Chief of Staff] First Guards Tank has been assigned a historic mission: to be the first to break into Berlin and hoist the Victory Banner. Personally charge you with organising and execution. From each corps send up to one of the best brigades into Berlin and issue following orders: no later than 0400 hours morning 21 April at any cost to break into the outskirts of Berlin and report at once for transmission to Comrade Stalin and press announcement. Zhukov.

‘ Zhukov’s concern that Stalin be informed as soon as possible after the entry of Soviet troops into Berlin is understandable. His concern that the press also be notified the moment that his soldiers entered the German capital is indicative of the psychological importance of this battle to the weary Soviet soldiers, as well, perhaps, as of the atmosphere of competition pervading the race to Berlin.’

Naturally Zhukov wasn’t the only one thinking along these kinds of lines. Even before the commander of First Belorussian had issued his order, his rival in the First Ukrainian had radioed orders of his own to the commanders of his Third and Fourth Guards Tank Armies: ‘Personal to Comrades Rybalko and Lelyushenko. Order you categorically to break into Berlin tonight. Report execution. 1940 hours, 20.4.45. Konev.’

Almost recklessly, Konev pressed his tank commanders on towards Berlin, urging them to abandon the normal concern for maintaining protected flanks. Years later, Konev mused that his generals must have thought he had lost all sense. ‘At that moment I knew what my tank commanders must be thinking: “Here you are throwing us into this manhole, forcing us to move without strength on our flanks – won’t the Germans cut our communications, hit us from the rear?’” But it worked. Within no more than 24 hours, Rybalko and Lelyushenko had raced 61 and 45km (38 and 28 miles) respectively; by nightfall Third Guards Tank Army was fighting in Zossen, only 40km (25 miles) from Berlin.

Zossen was the location of the supreme headquarters for both the OKH and OKW, though these had hastily evacuated just before the Soviets arrived. One of the OKH’s convoys, heading south to Bavaria, had been mistaken for a Soviet column, and was bombed and destroyed by the Luftwaffe. The German defence was by now almost completely on the run. General Heinrici felt that there was really only one last hope to avoid total annihilation by the Soviets. He had to ensure that the battle for Berlin remained outside the city. House-to-house street fighting, he knew, would be a catastrophe: the outmanned Germans’ tanks and artillery would be rendered useless, and the slaughter of civilians would be horrific. The only way to ensure fighting outside the city was to pull back the remains of Busse’s Ninth Army immediately, before it could be encircled by the First Ukrainian. But Hitler had ordered that the Ninth was to hold its position on the Oder. Heinrici attempted, in the most convincing way he knew how, to get the order remanded. In utter frustration he told Krebs to convey to Hitler that if his request was not met, then ‘since this order endangers your [Hitler’s] well-being, has no chance of success and cannot be carried out, I request you to relieve me of my command and give it to somebody else. Then I could do my duty as a Volkssturm man and fight the enemy.’ The incredulous Krebs told him he would pass the demand along; a short time later he phoned back that the Ninth was to maintain its position, and all available forces were to move into the gap between Busse’s army and 5chörner’s Army Group Centre.

It was clear at this point to Heinrici that the battle for Berlin was lost. Touring the front-lines that night, he noted an air of collapse affecting the forces. Everywhere he went he found troops – individuals and ragged units – in obvious retreat. ‘I didn’t find one soldier who didn’t claim to have orders to get munitions, fuel or something else from the rear.’ The area around Eberswalde, north-east of Berlin, was in particular disorder. Heinrici found whole units even S5 – resting in the woods or retreating with the civilian refugees; it was only with some effort that he managed to reorganise and deploy these soldiers. Meanwhile, the Fuhrer conference broke up around 0300 hours on a note of almost comic desperation. Hitler railed that all of ‘his’ problems were caused by the treason of the Fourth Army, the unit which had been mauled so badly by Konev’s forces on the first day of the attack. When Walter Hewel, Von Ribbentrop’s representative from the Foreign Ministry, gingerly suggested that any diplomatic initiatives would have to begin immediately, Hitler turned and ‘with tired and flagging gait’, according to one of his officers, muttered, ‘Politics. I have nothing to do with politics any more. That just disgusts me.’ In a hint of what he was beginning to contemplate, he turned back to the assembled men and added: ‘When I am dead you will have to busy yourself plenty with politics.’

The next day, 21 April, at 1130 hours the central shopping district in Hermannplatz came under direct artillery fire, blowing shoppers and passers-by to bits. Soon after that, shell after shell began pounding the very heart of the Nazi empire: the Reichstag was hit, the huge cupola crashing down into the building and over the street; the Brandenburg Gate had one cornice blown off; the Charlottenburg Palace went up in flames. A foreign correspondent who witnessed the barrage reported that at least one shell was falling every five seconds in the central government district in Wilhelmstrasse. Everywhere the city was strewn with rubble, burning vehicles, and the dead and injured.

Earlier that morning, the first elements of Zhukov’s forces had entered the north-eastern outskirts of Berlin. Kuznetsov’s Third Shock Army with First Mechanised Corps had fought their way into Weissensee and opened up a route into the city. In the course of the day, Fifth Shock Army, supported by 12th Guards Tank Corps, also broke into the city’s northern suburbs at Hohenschonhausen and Marzahn. In Bernau, Captain Sergei Golbov watched the surviving German soldiers emerge in surrender from their defences: ‘grey-faced, dusty, bodies sagging with fatigue’, they seemed to him a sorry lot. Golbov and the other Red Army officers were astonished to see one German officer stagger towards them, waving his blood-spurting arms, and shouting in Polish that they must leave his wife alone. Bandaging the wrists where the German had slashed them, Golbov replied that he had far more important things to do than harass the man’s wife, and sent him back to the medics. At least a few Germans in Neuenhagen-Hoppegarten, 19km (12 miles) east of Berlin, were overjoyed to see the arrival of the Soviets. A few secret Communists had burned their Volkssturm armbands and turned out with a white banner and huge smiles to watch the Red Army enter. And the behaviour of these units gave them reassurance that their dreams of the Communist society were true, and Goebbel’s stories of the depredations of the Soviet soldier only propaganda.

Fearful of falling victim to a German sniper or machine-gun nest, the advancing Soviet units used armour and artillery to completely pulverise any building which offered a vantage point.

Soviet soldiers move cautiously from house to house) warily looking up into the windows and into the basements for hiding German soldiers and weapon stores.

Into the City

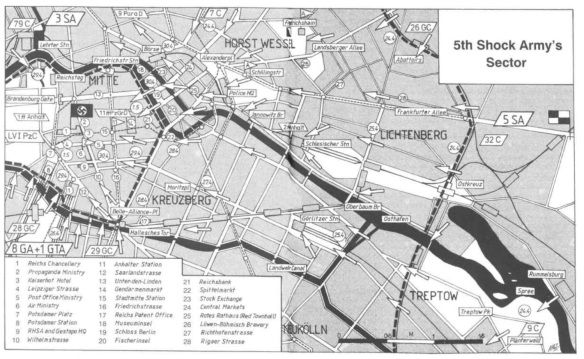

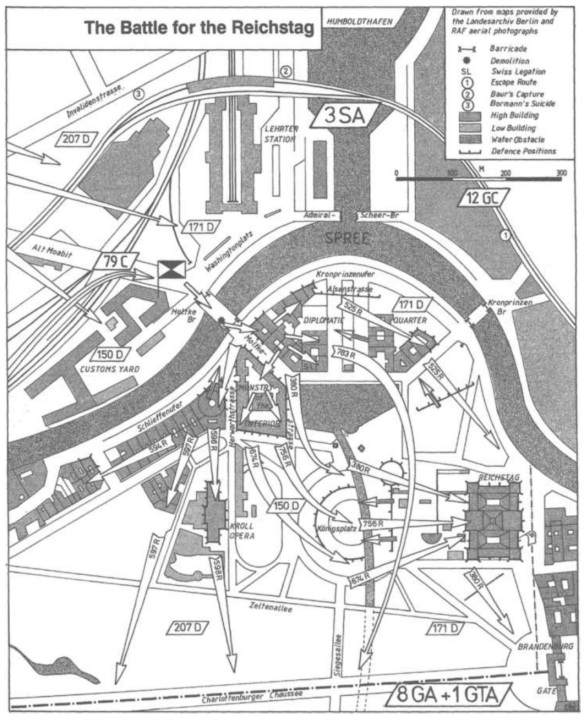

Sunday 22 April was a day of dashed hopes on both sides of the titanic battle being waged over Berlin. For Adolf Hitler, the day began with hopeful expectations that the ‘Steiner Attack’ would at last rout the Soviets before Berlin. Instead, it ended in an atmosphere of gloom and pessimism, with the Fuhrer announcing to his frightened staff that the war was lost and that he would commit suicide rather than face the disgrace of conquest. On the other side, First Ukrainian Front’s Marshal Konev also began the day with strong hopes; those of being the one to claim the laurels for the capture of Berlin. But by early the next morning, Konev was informed that Stalin and the Stavka had issued new demarcation orders for the two fronts, awarding Zhukov’s First Belorussian Front the honour of penetrating to the centre of Berlin and capturing the Reichstag. During the night, Zhukov had ordered a regrouping of the lead units of First Belorussian to break the stall on the left flank. Third Shock Army, in the north, was ordered to direct its attack away from the northern suburbs and into the centre of Berlin, in the hopes that it would take some of the pressure off the eastern approaches where Chuikov and Katukov were having so much difficulty. Colonel General Kuznetsov, Third Shock’s commander, accordingly redeployed three of his rifle corps into assault groups and assault squads for urban combat and advanced into northern Berlin. Rather than fight for individual buildings, however, the Soviets first subjected the sector to a punishing artillery barrage, with Katyusha rocket launchers firing salvoes of phosphorous rockets into suspected strong-points. Then the tanks moved in, with orders to obliterate everything that ·could harbour a sniper. With the urban landscape disintegrating under flames and exploding concrete, the Red Army infantrymen moved methodically from rubble heap to rubble heap, clearing out the cellars with flame-throwers, anti-tank rifles, and explosives. The terrified civilians who had taken refuge below now found themselves in the thick of the fighting. Those who fled or were dragged out on to the streets became targets for the Soviet fighter planes swarming overhead.

By 1000 hours, Kuznetsov’s assault groups were pressing their attack into Weissensee. A few squads from the 11th SS Nordland Division and small groups of poorly equipped Volkssturm units were about the only resistance, although the antiaircraft guns with barrels depressed to ground level did create some problems. The neighbourhood, once a bastion of German Communist sympathy, surrendered quickly. The Red Army soldiers rapidly and professionally secured the sector, rounded up the surviving Germans and put them through a hasty screening process. Some of the men spoke excellent German, but most of the interrogations were conducted by women from the interpreter units which accompanied the first echelon troops. Most of the captured women and those men who could provide convincing anti-Nazi credentials were put to work cleaning up the devastation, while the rest were sent to the rear as prisoners. The soldiers of Third Shock Army pushed on into Berlin.

To the east, Chuikov’s Eighth Guards and Katukov’s First Guards Tank Armies continued to encounter heavy resistance at Erkner and Petershagen, but by the afternoon they had managed to reach the River Dahme, with the Spree only a short distance ahead. An assault crossing was planned for the next day, which would finally bring the units designated to take the Reichstag into Berlin proper. On Chuikov’s and Katukov’s right flank, Fifth Shock Army, supported by 12th Guards and 11th Tank Corps, also managed to bite deeply into Berlin’s eastern defences, driving into Kaulsdorf, Biesdorf, and Karlshorst. On this side of the battle, too, large numbers of prisoners were taken, though General Katukov found himself saddled with one group of prisoners for which he had not been prepared. During the attack on Erkner, he had received a bizarre call from one of his commanders informing him that he had just taken prisoner a number of Japanese. His tanks had happened upon a diplomatic mission of the Japanese Empire, with which the Soviet Union was not yet officially at war. Katukov grimaced, knowing this would be an annoying diplomatic flap, and ordered the Japanese to be brought immediately to his headquarters.

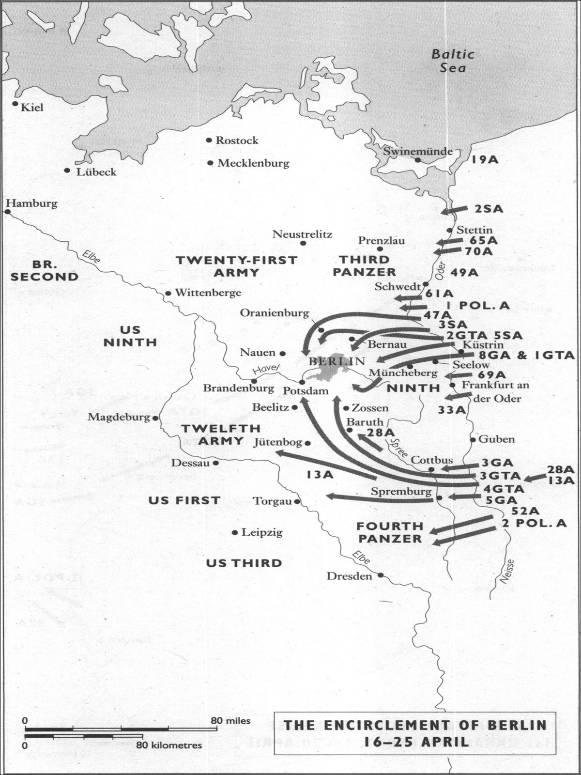

The Soviets continued their relentless drive towards its heart, with five rifle and four tank armies now committed inside Berlin. In the south, First Ukrainian Front’s Third Guards Army, reinforced by three rifle divisions from the 28th Army, continued to strike due north towards Tempelhof, while Lelyushenko’s Fourth Guards Tank Army also swept around the city’s south-western edge. For the first time since the Berlin assault began, units of First Belorussian and First Ukrainian Fronts were in a position to co-ordinate their efforts. Lieutenant General F.I. Perkhorovich’s 47th Army of the First Belorussian drove off to the west, and then back to the south-east into Berlin, while Ninth Guards Tank Corps, also from the First Belorussian, was designated to strike along the north-western edge, and then south-west towards Potsdam to link up with Konev’s forces. By 1900 hours on 22 April, the Ninth Guards tanks and the infantry of 125th Rifle Corps had succeeded in fighting their way across the Havel and had established a bridgehead east of Hennigsdorf.

Zhukov also began immediately implementing Stavka’s new orders. He directed 47th Army to push with all speed towards Spandau and send one division with a brigade from Ninth Guards Mechanised Corps to link up with Lelyushenko’s tank army at Potsdam. He also flatly ordered Chuikov and Katyukov to force a crossing of the Spree and break into the Templehof, Steglitz, and Marienfelde areas no later than 24 April. Bogdanov’s Second Guards were ordered to launch a simultaneous attack against Charlottenburg, in the city’s western districts. The commanders of First Belorussian were told to organise their units into assault squads for street fighting, and to commence round-the-clock operations, day and night, with combined infantry and tanks. To this end, Zhukov had redeployed several tank corps and brigades to the primary assault units: Third Shock Army, Fifth Shock Army, and Eighth Guards Army. After being subjected to some of the worst fighting in the Berlin campaign, the First Belorussian Front at last began making some real progress. Kuznetsov’s Third Shock, reinforced by Ninth Tank Corps and joined by First Mechanised and 12th Guards Tank Corps, blasted its way to the Wittenau-Lichtenberg railway line deep in the northern and north-eastern suburbs, and cleared out a number of large apartment blocks. Berzarin’s Fifth Shock, with 11th Tank Corps adding to its strength, reached the Spree near Karlshorst and managed to gain a tenuous bridgehead on its far side, ready for a full-scale assault crossing. Chuikov’s Eighth Guards smashed its way up to the Spree and Dahme rivers. On reaching the eastern bank of the Spree, they discovered a number of abandoned barges, motorboats, and other watercraft, which they quickly pressed into service. The Dnieper Flotilla had also made its way up the rivers and assisted all of the units in their crossings. Chuikov’s soldiers and tanks quickly destroyed the German resistance in this sector, took Wuhlheide, then Adlershof, and by the evening of the 23rd were fighting in Alt-Glieicke and Bohnsdorf, in an ideal position for the link-up with Rybalko.

That night, guns fired celebratory salvoes in Moscow. The greatest battle of the war was reaching its climax. Berlin was surrounded on three sides, with only three roads out to the west. With Zhukov’s successes, the final trap would be sprung within days, even hours. But it had cost the Red Army heavily. Losses were staggering, with many companies down to as few as 20-30 men. Regimental commanders were forced to regroup their men into two battalions, rather than the usual three. The forests, roadsides, and gardens of eastern Germany, from the Oder to Berlin, were filled with tens of thousands of hastily buried dead Red Army soldiers. But they were littered, as well, with the corpses of German soldiers, civilians, and entire towns.

The fighting was extremely brutal and desperate, exactly the kind of terrifying, close-quarters urban combat both sides had hoped to avoid. After artillery and air support had reduced the most likely bunkers and fortified positions to heaps of concrete, wood and glass, the Soviet infantrymen cautiously but efficiently scurried from ruin to ruin, flinging open doors, clearing cellars and buildings with machine-guns, grenades and flamethrowers, while the tanks blasted anything large enough to harbour a sniper or machine-gun nest, and roared over the bodies of those too wounded or slow to dodge them.

Once across the Teltow, Third Guards Tank Army’s forces pushed on towards Schmargendorf, Steglitz, Grunewald, and Pichelsdorf. Their goal was to link up with Bogdanov’s units driving down from the north-west, and cut off those German forces still holding Potsdam and Wannsee. Within a few hours, Seventh Tank Corps had made it, pushing all the way through to the Havel, within 1830m (2000yds) of Bogdanov’s tanks. Further east, Chuikov’s Eighth Guards had also gained a crossing over the Teltow and were driving towards Tempelhof airfield. The Soviet commander was determined that if Hitler were still in the city, he would not be allowed to escape. A single. airplane out of Tempelhof to Bavaria seemed the most likely scenario for the Fuhrer’s attempted flight, so the capture of the airfield was -given a top priority. Although no such plans existed by this time, the airfield was heavily defended. Dug-in tanks, SS troops, and anti-aircraft batteries ringed the field with its underground hangars which, according to the accounts of captured German soldiers, held a number of aircraft with a relatively large supply of fuel. Chuikov sent two rifle divisions to outflank the airfield from the west and east, then sent the bulk of his army up from the southern perimeter. The Soviet tanks raced onto the runways, raking the area all around with machine-gun fire and tank guns, and spun around to block the entrances to the hangars. By noon, Tempelhof was under Red Army control. While a few German planes still attempted to fly into the city via Gatow to the East-West axis, by this time the Soviets were making very few sorties for ground support. The dense smoke rising in hundreds of columns all over the city, reducing visibility to a few hundred yards, made flight extremely hazardous.

Meanwhile, further east, the 39th Guards Rifle Division had advanced to the Spree and, using the shattered remains of a bridge, gained a foothold on the western bank. House-to-house fighting ensued, with the Soviet troops often dynamiting ‘tunnels’ through the buildings to pass from street to street. Under intense pressure to accelerate the liquidation of each sector and get to the ‘main prize’, both Zhukov and Konev made heavy use of artillery to obliterate an area before the troops moved in. The average assault squad was supported by no fewer than three or four field guns. Forced to divert his drive to the city’s west side to deal with the Wannsee garrison some 20,000 German troops Lelyushenko incurred the wrath of Konev, who impatiently demanded that Fourth Guards Tank Army use 10th Mechanised Corps to take Wannsee no later than 28 April – and send Sixth Mechanised Corps on to Brandenburg. In First Belorussian’s sector, Third Shock Army was ordered to strike towards the Tiergarten (zoo), which lay hard on the west side of the central government district, and make contact with Chuikov’s Eighth Guards, who had succeeded in gaining the Landwehr canal. By the end of the following day, 27 April, German control of Berlin, the capital of the Thousand-Year Reich, was a narrow strip no more than 5.5km (3.5 miles) at its widest, running roughly 16km (10 miles) east to west.

With the Soviets closing in on all sides, bringing with them total destruction block by block, any kind of real co-ordination of the military elements in the city was practically impossible. Much of the resistance was carried out by desperate Volkssturm and Hitler Youth units. Shortages of all manner of supplies were chronic. The new Commandant of the city garrison, General Weidling, pleaded with the Luftwaffe for air-drops, and a few Messerschmitt 109s and Junkers Ju 52s parachuted some medical supplies into the dying city, but only small quantities of ammunition were flown in. At one point, the East-West Axis, which was being used as a landing strip, was closed to further flights when a Junkers crashed into a house. Attempting to destroy bridges and other key installations as they withdrew towards the city centre, the Germans were frustrated by the shortage of explosives (as well as by Speer’s refusal to supply bridge plans) and had to resort to improvised aerial charges. Casualties in the city mounted horrifically. The hospitals and refugee centres were jammed full, though most of the dead and wounded remained scattered in the streets and piled in cellars or under collapsed buildings. Inside the two massive flak towers located in the central district, thousands of people huddled together while Soviet shells thumped into the concrete walls and steel-shuttered windows, the impressive batteries of anti-aircraft guns on the roof now all but useless.

Amidst reassuring reports from Krebs that the defence was holding and that the Luftwaffe was preparing to airlift reinforcement troops into the city, Weidling reported to Hitler at 2200 hours that the garrison had only a two-day supply of ammunition, at best. He outlined the civilian population’s catastrophic situation, with food and water unavailable, and the dead and wounded lying untended. The general insisted on an immediate attempt to breakout to the west. He proposed to organise three ranks for the effort: the lead echelon to consist of the Ninth Parachute and 18th Panzer Grenadier Divisions reinforced by all of the available tanks and self-propelled guns; followed by a second formed from ‘Group Mohnke’ and a Marine battalion and including the bunker’s headquarters staff; and a third from what was left of the Münchenberg Panzer Division, the Bahrenfanger battle group, 11th SS Nordland Division, and a rearguard of the Ninth Parachute. It is doubtful whether such an effort could have succeeded in breaking out of the besieged city, particularly in the absence of any accurate information on the position of Wenck’s 12th Army. In any event, Hitler refused to consider any kind of ‘retreat’.

THE GERMAN DEFENSE OF BERLIN, 1945

By OBERST WILHELM WILLEMER