On 23 May 1618 two of the Catholic regents of Bohemia and their secretary were ‘defenestrated’ from the Hradcin Castle in Prague by Count Mathias Thurn (1567-1640) and his Protestant acolytes. They survived: ‘held aloft by angels’, claimed the Catholics; ‘landed on a dung heap’, replied the Protestants – the moats of seventeenth-century forts were usually replete with rubbish and outpourings from latrines. Now in open revolt against the Holy Roman Emperor, Matthias, the Bohemian rebels invited Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate to become their king. He accepted, expecting assistance from the member states of the Protestant Union, of which he was director, but, alarmed at Frederick’s impetuosity, most demurred. Isolated, Frederick paid Count Ernst von Mansfeld and Prince Christian of Anhalt-Bernburg (1568-1630) to raise an army in support of Thurn.

While the major Protestant countries – England, Sweden and the Netherlands – plus France, Catholic but anti-Habsburg, dithered, Catholic rulers acted. The Catholic League pledged Matthias its army of 30,000 men under the highly experienced Tilly. Together with the Frenchman Charles de Longueval, Count of Bucquoy (1571-1621 ), who directed the Austrian contingents, Tilly swept into Bohemia through Lusatia and Upper and Lower Austria , whilst the Spanish Army of the Netherlands , commanded by Spinola, Invaded the territories of the Palatinate along the Rhine. In less than an hour on the morning of 8 November 1620, across the slopes of the White Mountain outside the walls of Prague, Tilly and Bucquoy smashed the Bohemian Army of Anhalt, Thurn and Mansfeld.

So began the Thirty Years War. Struggles between Protestant and Catholic had occupied much of the sixteenth century, reaching a temporary hiatus after the termination of the French Wars of Religion in 1598. In the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, the princes, dukes, counts, knights and Imperial Free Cities, numbering over 330 separate polities all owing allegiance to the Habsburg emperor in Vienna, used the pause to prepare for renewal of hostilities. Landgrave Maurice of Hesse-Kassel founded a militia of 9,000 men in 1600 and a training school for officers in 1618. The Prussian estates voted funds in 1601 to refortify the ports of Memel and Pillau and maintain two warships to patrol the Baltic. Between 1553 and 1585 the electors of Saxony founded a magnificent arsenal in Dresden. After 1600 the Elector Palatine refortified Frankenthal and Heidelberg and, in 1606, created a fortress-city at Mannheim. Calvinist Hanau, allied to the Palatinate, received a set of artillery fortifications between 1603 and 1618. The Catholic powers in the Rhineland reciprocated. Ehrenbreitstein, overlooking the confluence of the Rhine and the Mosel at Koblenz, was fortified by the Elector of Trier, whilst Christopher von Sotern, Bishop of Speyer, built the massive fortress of Philippsburg at Udenheim on the Rhine south of the Palatinate. Construction, begun in 1615, took eight years.

Tranquility in the empire depended upon the Religious Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which had established the principle of cuius regia, eius religia – the religion of the ruler determined the religion of the state. Protestant princes, who had nationalized the church, thereby greatly increasing their territorial, financial and administrative power, sought to consolidate their gains. Catholic rulers were prepared to support the emperor’s attempts to recover lands lost to the heretics in return for political rewards. Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria, contravened the Religious Peace of Augsburg in 1608 by seizing and catholicizing the Lutheran Imperial Free City of Donauwörth, which housed a vital bridge across the Danube on Bavaria’s northern border. At the Imperial Diet in the following year, the Protestant members walked out in protest to found the Protestant Union, a ten-year defensive pact ultimately comprising nine princes and seventeen Free Cities. Directed by Elector Frederick IV of the Palatinate (r. 1583-1610), its leaders were Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg (r. 1608-20), the Duke of Württemberg, and the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. France, weakened by three decades of civil war, supported the union as a cheap weapon in her contest with the Habsburgs. In response, on 10 July 1609 Maximilian of Bavaria formed the Catholic League. Although it eventually included fifteen archbishoprics and bishoprics, the principal member was Bavaria, but Philip III of Spain subsidized Tilly and the league’s army. The states of the empire were ready to act as surrogates in the rivalry between Habsburg Spain and Valois France.

The Twelve Years Truce between Spain and the rebellious Dutch expired in 1621. In order to position herself for the resumption of hostilities, Spain became directly involved in Imperial affairs because of her concern for the ‘Spanish Road’, a military corridor linking Lombardy with the Spanish Netherlands via the Valtelline, the Tyrol, Upper Swabia and the Rhine valley. Because English and Dutch naval power blocked the sea route from Iberia to the Netherlands, Spain relied upon the Spanish Road to supply and reinforce her armies in the Low Countries. Control of the Valtelline was vital, and in 1623 Spain occupied the Canton of the Grey Leagues, the Grisons, through whose territory the Valtelline extended. Spinola’s seizure of Jülich in 1622 had also improved communications along the road, and so too did the occupation of Alsace by the Austrian Habsburgs in the same year and the capture of Frankenthal in the Rhenish Palatinate in 1623.

Following the collapse of the Bohemian revolt at the White Mountain, the forces of the Austrian Habsburgs, now answerable to Emperor Ferdinand II, and the Catholic League attacked the lands of the Elector Palatine. Some Bohemian garrisons held out – Pilsen surrendered in 1621 and Wittingau in 1622 – but Frederick was without an army until Mansfeld, his pockets stuffed with Dutch and English money, took over the 21,000 troops of the dissolved Protestant Union. He promptly withdrew into Alsace to recruit his command up to 43,000 men, where the small corps of Margrave George Frederick of Baden (1573-1638) joined him. Mansfeld and Baden interrupted Tilly’s campaign of conquest in the Rhenish Palatinate at Wiesloch, 12 kilometres south of Heidelberg, on 27 April 1622 but failed to continue their co-operation, and Baden was smashed by Tilly at Bad Wimpfen, on the Neckar to the north of Heilbronn, on 6 May. Tilly next marched to block the small army of Christian of Brunswick (1599-1626), a young adventurer of questionable judgement, whom he defeated at Hochst in the Odenwald on 20 June. Thoroughly beaten, Frederick dismissed Mansfeld and Baden and retired into exile in the Netherlands. Mansfeld and Baden sold their army to the Dutch but, while attempting to join them in East Friesland, Christian of Brunswick was intercepted by Tilly on 6 August 1623 at Stadtlohn, close to the Netherlands’ eastern border.

Although the Dutch had attacked Spain indirectly by providing financial support to Frederick of the Palatinate, the termination of the Twelve Years Truce obliged them to confront their enemy openly. Spinola, his supply line via the Spanish Road secure, took the offensive, capturing Jülich in February 1622 and besieging Bergen-op-Zoom in the autumn. This siege was raised on 4 October when Mansfeld’s army arrived in the Netherlands and defeated Fernandez de Cordoba at Fleurus, 26 August. However, Spinola continued his offensive in 1624 culminating in the successful siege of Breda, 28 August 1624 – 5 June 1625. The Count-Duke of Olivares, who directed Spanish foreign and military policy for Philip IV until 1643, intended to attack the Dutch both militarily and economically, so he formed an anti-Dutch trading league called the almirantazgo, comprising Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, the Hanse towns and Poland, with co-operation from the Catholic League and the emperor. In response, during June 1624 the Dutch formed an alliance with England and France committed to the restoration of Frederick to the Palatinate. The marriage of Prince Charles, the future Charles I of England, to Louis XIII’s sister, Henrietta Maria, sealed the agreement.

MERCENARIES AND THE MILITARY ENTREPRENEUR

Although the wars of the sixteenth century had demonstrated the inefficiency of mercenaries, it was not until the second half of the seventeenth century that standing armies partially replaced the ‘military entrepreneur’ and his hirelings. The experiences of the Thirty Years War were instrumental in bringing this about; standing armies were exceptional in 1600 but commonplace within a century. The standing army was scarcely a novel concept. The Roman Army was the most notable amongst numerous predecessors, whilst many rulers during the Middle Ages retained permanent garrison troops in their strategic fortresses as well as small units of bodyguards. In addition to the Yeomen of the Guard (1485) and Gentlemen Pensioners (1539), Henry VIII of England had 3,000 regular troops garrisoning the permanent fortifications along the south coast and the Scottish border.

Charles VII of France (r. 1422-61) had founded a standing army in 1445 during the final stages of the Hundred Years War, the compagnies d’ordonnance, which Louis XI (r. 1461-83) reorganized into the Picardy Bands and trained according to the Swiss model. Under Francis I (r. 1515-47) this cadre matured into a standing army composed of volunteers recruited through a state agency. The Burgundian standing army of Duke Charles the Bold (r. 1467-77) imitated the French pattern. Between 1445 and 1624 the peacetime French military establishment ranged between 10,000 and 20,000 troops, who guarded the royal person and garrisoned the frontier strongholds. During wartime this cadre was expanded to a maximum of 55,000, the level reached under Henry IV during the final stages of the French Wars of Religion. Individual field armies did not normally exceed 20,000 men, the most that could be supplied and administered on campaign.

The Ordinance of Valladolid of 1496 prepared Spain to follow a similar course. Also adopting Swiss methods, Gonsalvo de Cordoba reorganized the Spanish foot in 1504 as the Ordinance Infantry. Half the men were armed with the long Swiss pike, one-third with a round shield and thrusting sword, and the remainder with the arquebus. In 1534 this system matured into the tercio, which, befitting the age of the Renaissance, pursued the example of the internal articulation of the Roman legion. The tercio, a combination of pikemen and arquebusiers, was initially organized into twelve companies of 250 men, each subdivided into ten esquadras of twenty-five. Pay was monthly, deductions being made for medical insurance, but the soldier could earn additional money via long-service and technical skill bonuses. Every tercio was equipped with a commissariat, legal section and health service consisting of a physician, surgeon, apothecary and ten barbers. In action the tercio was tactically flexible, capable of forming task forces – escuadrons – mixing varying numbers of troops and types of weapons. The sixteenth-century Spanish standing army operated principally beyond the Iberian Peninsula, garrisoning bases in northern Italy, countering the rebellious Dutch in the Netherlands and Protestants in Germany, and opposing the Muslims in North Africa.

In Germany the military systems that fought the Thirty Years War were in place by the 1590s. Militias provided a minimum level of defence and deterrence in nearly all states. Ancient feudal obligations, including mass mobilization Landsturm) and personal cavalry service by members of the nobility, continued as mechanisms of last resort. Larger states – Bavaria, Saxony and the Palatinate – retained small bodyguard and garrison cadres capable of wartime augmentation through the recruitment of mercenaries and the pressing of militiamen. The first proper German standing army belonged to the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperors. Since 1535 the Habsburgs’ borders with the Ottoman Empire in the northern Balkans had been protected by a permanent militia organization, the Militargrenze, whilst garrison regiments were established in the Hungarian and Austrian fortresses during the 1580s. There were also some cavalry units, a naval flotilla on the Danube, and a military administration attached to the Court War Council (Hofkriegsrat). After the outbreak of war in 1618, contractors, most already closely associated with the royal house, raised new regiments. Gradually these mercenary leaders mutated into officers of the state army, to be joined by a host of minor nobility and imperial knights in pursuit of the new career opportunities and cash rewards.

There was rarely a shortage of mercenaries; wars peppered the continent, and accommodating their human requirements was a major international business. Rulers contracted with mercenary generals, who then subcontracted to colonels and captains. Most mercenary captains, over 1,500 of whom were active in Germany during the Thirty Years War, maintained their companies on a permanent basis. Many smaller Italian and German states paid an annual retainer to a military entrepreneur in the knowledge that he could exploit his contacts to raise troops quickly in an emergency. Periods of agricultural dearth – and there was at least one bad harvest every seven years – plus overpopulation in Ireland, Scotland, Poland, eastern Germany, Switzerland, Serbia and Croatia, produced fodder for the recruiting parties. A soldier’s life was not unattractive. Battles were infrequent, there was the prospect of loot and plunder, whilst living conditions were no worse than those endured by civilians. The greatest danger was disease, particularly prevalent in crowded and insanitary camps.

Born in Luxembourg, Count Ernst von Mansfeld (1580-1626) was the leading Protestant military entrepreneur. He specialized in the swift production of large, poor-quality armies but lost them equally quickly. Should Mansfeld so miscalculate that he had to fight a battle, his ill-equipped armies invariably disintegrated. However, his prices were very low. He served the Habsburgs between 1594 and 1610 before transferring to the Protestant Union from 1610 to 1617. After a year with Savoy he was appointed general to Frederick V of the Palatinate Sacked in 1622, he entered Dutch service, but his funding expired in 1623 so he disbanded his troops, most entering Dutch service, and looked around for a new employer.

On 14 April 1624 he arrived in England to raise 12,000 men with whom to recover the Palatinate for Frederick. France and England had each agreed to meet half the costs of Mansfeld’s expedition, whilst the former undertook to provide 3,000 cavalry to join the English infantry when they arrived in France prior to marching east into Germany. An international celebrity, Mansfeld was lodged in state apartments at Whitehall. Despite orders to every parish to conscript fit young men – the trained bands, the elite of the county militias, were sacrosanct- mostly the unemployed, social misfits and petty criminals were listed, ideal material for Mansfeld, who specialized in destruction and pillage. En route to Dover they deserted in droves, and those who remained were thoroughly disruptive. Mansfeld had been given £55,000 but was determined to spend as little as possible, refusing to take financial responsibility for his men until their arrival in Dover. Mansfeld then ignored his instructions and decided to march to the Palatinate via the Netherlands rather than France. When he landed on the island of Walcheren in the estuary of the River Schelde, no preparations had been made and the army evaporated through starvation and disease.

Mansfeld’s English contract illuminated the salient disadvantages of mercenaries. Although good-quality companies could be effective, the bargain- basement varieties were useless. Expecting their men to support themselves through pillage and requisition, entrepreneurs made scant supply arrangements. Mercenary armies were thus particularly unsuitable for siege operations. Whereas marching troops could usually find enough forage and sustenance, immobile troops were liable to starve. Finally, as Mansfeld demonstrated, once money had been handed over, the hirer surrendered control and the mercenary leader could conduct operations as he wished. The mercenary system offered few advantages except that troops could be raised rapidly and the state avoided having to maintain an expensive military infrastructure. The latter point was persuasive at the start of the Thirty Years War but experience soon taught that the loss of political authority reinforced the case for maintaining a standing army.

DENMARK JOINS THE WAR

Christian IV the alcoholic King of Denmark, volunteered to lead a new coalition against Emperor Ferdinand. Although Sweden was Denmark’s main rival, the advance of the Imperial and Catholic League armies into northern Germany threatened both his southern border and his territorial ambitions. Christian had founded the port of Glückstadt on the Elbe in 1616 as a rival to Hamburg and was anxious to acquire the bishoprics of Verden, Bremen and Osnabriick, which controlled the lands between the Elbe and the Weser and thus the lucrative river traffic. Moreover, he was rich from the tolls that Denmark charged on every ship passing through the ‘Sound’, and there was no better way for a king to spend his money than by starting a war.

Lacking both support from his coalition partners and reliable knowledge of the political situation, in January 1625 Christian advanced across the Elbe with 17,000 men, a mixture of mercenaries and peasant conscripts, heading for Hameln on the Weser. Expecting to encounter only Tilly’s army, billeted in Hesse and Westphalia, Christian ran into Wallenstein, whose 30,000 men had marched north to Halberstadt and Magdeburg. Luckily for Christian, Tilly and Wallenstein quarrelled and failed to combine, allowing the Danish army to run away. Christian promptly informed his partners that he would make peace if they did not come to his aid. Accordingly, the Hague Convention of 9 December 1625 initiated a loose alliance between England, Denmark, the Dutch Republic and Frederick of the Palatinate, supported by France, Bethlen Gabor, Prince of Transylvania (r. 1613-29), and his suzerain, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Supplied with English and Dutch gold, King Christian undertook to attack Lower Saxony while Christian of Brunswick invaded the Wittelsbach bishoprics in Westphalia and the lower Rhineland. Mansfeld, the coalition’s generalissimo, decided to advance along the Elbe into Silesia, ravaging the Habsburg lands, before joining Bethlen Gabor, who was to operate against Austria and Moravia. The scheme was too complicated -liaison between the various forces was bound to break down – and Emperor Ferdinand had reorganized his armies. Bavaria, whose Army of the Catholic League was bearing the brunt of the war thus allowing the emperor’s troops to operate against Bethlen Gabor in Hungary, asked Ferdinand to contribute to the campaigns in Germany. Already chafing at the political restraints imposed by his reliance on Tilly and the league, Ferdinand turned to Wallenstein.

Arrogant, vain and ambitious, Albrecht Wenzel von Wallenstein (1583-1634) was amongst the minority of Bohemian noblemen who had supported the Habsburgs during the Bohemian Revolt. In 1609 he had married an elderly but rich Czech widow, Lucretia Neksova, owner of vast estates in Moravia. Her death enabled him to buy, at knock-down prices, lands confiscated from rebellious Protestants. Although blessed with some slight previous military experience – he had fought against the Hungarians in 1604, provided mercenaries for Ferdinand of Austria’s war with Venice in 1617, and rejoiced in the title of Colonel of Prague – Wallenstein was more businessman than soldier. Placing his agent, the Antwerp banker Johan de Witte, in charge of logistics, Wallenstein answered the emperor’s call by offering to raise 24,000 troops at his own expense, a proposal that Ferdinand found irresistible. A contract was finalized in April 1625, and when Wallenstein exceeded his target by recruiting nearer to 50,000, on 13 June a grateful Ferdinand created him Duke of Friedland. Wallenstein’s quid pro quo was to be allowed to recover his expenses and appoint his own officers.

Wallenstein provided equipment, weaponry and foodstuffs for his troops from his personal estates but made his profit through the ruthless extortion of ‘contributions’. When his troops occupied a region, every town and village was assessed and ordered to pay a sum in cash or kind. Failure to deliver by the deadline saw the houses put to the torch (‘brandschatzen’) and hostages executed. It was a slight improvement over random pillage a la Mansfeld, but in order to operate the system, sizeable tracts of land had to be occupied and contributions frequently exacted from friendly as well as hostile areas. Should a region become economically exhausted, then the army had to move whether or not this served a strategic purpose. Wallenstein’s men were barely the superiors of Mansfeld’s, but better equipment and cohesion gave them the advantage during the Danish War.

Opposed to Tilly and Wallenstein, Christian commanded neither such numbers nor organization. Probably imitating the Swedish model of 1544, in 1614 he founded a small territorial army composed of conscripted peasants from crown estates. Seven years later the system was rethought. On royal and church lands every nine peasant households formed a ‘file’, which was obliged to provide a soldier who served for three years and, if not mobilized, worked on one of the farms and drew a wage. ‘Files’ could rarely afford to hire a substitute, so one of their own had to be ‘persuaded’. Conscripts drilled for just nine days a year and the highly unpopular scheme produced a low-calibre peasant army, hardly better than a militia. More significantly, in 1624 Christian formed a permanent corps of regular troops to garrison the three Danish fortresses on the Norwegian-Swedish peninsula and this became the cadre of the later Danish standing army.

Mansfeld’s campaign began discouragingly when his attempt to cross the River Mulde, a left-bank tributary of the Elbe, was checked at Dessau Bridge in April 1626. After regrouping, in June Mansfeld advanced again, the Imperial forces having been weakened by the need to send troops to quell a peasant revolt in Upper Austria. Erroneous intelligence (two words that are closely associated in military history) led Christian to believe that Wallenstein had committed his entire army to the pursuit of Mansfeld when he had actually sent a considerable corps to reinforce Tilly in Lower Saxony: Assuming that he was opposed by weak forces under Tilly, Christian marched south from Wolfenbiittel in August 1626 along the valleys of the Innerste and the Neile between the Hainberg and the Oderwald. Rain poured down and Tilly slowly withdrew, skirmishing with Christian’s vanguard, until he made a stand at the important road junction of Lutter-am-Barenberg. Christian blundered into Tilly’s position on 26 August and the battle was lost when the Danish cavalry defected. As the Danes straggled northwards towards Wolfenbiittel, their retreat was harried by ambushes that Tilly had placed during the fighting withdrawal to Lutter.

Mansfeld, closely followed by Wallenstein, joined Gabor in Silesia on 30 September 1626 only to discover that the latter was about to withdraw from the conflict. Gabor had received news of the sultan’s defeat by the Persians at Baghdad and, realizing that he could not fight without the sultan’s support, made peace with Ferdinand at Bratislava in December 1626. Abandoning his army, which now numbered no more than 5,000 men, Mansfeld rode south, heading for Ragusa (Dubrovnik) in Croatia to take up a pre-arranged contract with Venice, but died en route at Rakovica near Sarajevo on 29 November. His men subsisted in Silesia over the winter but surrendered to the Imperialists in July 1627.

Tilly and Wallenstein joined forces in 1627 to sweep through Saxony, defeat Christian at Eutin, and occupy the whole of the Jutland peninsula. Lacking a navy, Wallenstein could not capture the Danish islands, but by 1628 he and Tilly were established on the Baltic coast and had reconquered Germany for the Catholic faith. At the Peace of Lubeck on 22 May 1629, Christian was restored to his possessions on condition that he supported the Spanish and Imperial ambitions to control the waters of the Baltic by the creation of a navy at Wismar. To complete the zenith of Imperial power, Wallenstein was created Duke of Mecklenburg and a prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS

Warfare in the Baltic was dominated by the rivalry between Sweden and Denmark. Populations were sparse, resulting in both conscription and the widespread employment of mercenaries. Whereas campaigns in Central and Western Europe were conducted between late spring and mid-autumn, in the Baltic lands the summer season was shortened by spring mud, caused by the melting snows, and autumn rains. Usable roads were scarce everywhere in Europe but even more so in the North: armies often campaigned in the depths of winter when frost had hardened the ground. Ski-troops were regularly used in the wars between Sweden and Muscovy along the Finnish-Karelian border and between Sweden and Poland in Livonia. Four hundred reindeer pulled the supply sledges of the Swedish army that attacked the fortress of Kola on the White Sea in 1611.

Despite its remoteness, the Baltic was increasingly important to the European economy: Swedish copper and iron; Norwegian cod; Russian hemp, tar and timber; and, particularly, grain from Poland and German lands east of the Elbe. Much of the trade rested with Dutch and English merchants but every ship had to pass through the Sound, controlled by the Danes.

Gustav II Adolf, better known as Gustavus Adolphus, ascended the Swedish throne at the age of 16 during the Kalmar War with Denmark (1611-13). The Treaty of Knared brought peace at the price of Sweden’s surrendering in perpetuity Gothenburg and Alvsborg, possession of which had allowed the Swedes to outflank the Danish Sound tolls, unless she could redeem them by a payment of 6 million riksdaler within six years. Much to Danish annoyance, with the help of heavy taxation and Dutch loans, the money was paid in 1619 and the region reclaimed. At Stolbova in 1616, in return for renouncing her claims to Novgorod, Sweden received Ingria and Keksholm from Muscovy, completing a land bridge between Estonia and Finland and bringing the whole coast of the Gulf of Finland under Swedish occupation. Having achieved peace with both Denmark and Russia, Gustav turned his attention to Poland, his position strengthened by a fifteen-year defensive alliance with the Dutch, signed in 1614. A premature attempt to seize Pernau from Poland in 1617 misfired and Sweden agreed a two-year truce in 1618.

The failure at Pernau convinced Gustav that the Swedish Army needed radical reform. Accordingly, during the 1620s he improved the conscription machinery. The 1620 ‘Ordinance of Military Personnel’ registered all males over 15 years of age in every parish and grouped them into ‘files’ of ten men; as many as required could then be drafted from each file. Sweden-Finland was split into eight recruiting districts, subdivided into two or three provinces each raising one ‘provincial’ infantry regiment consisting of three field regiments comprising two 408-man squadrons apiece. Recruiting districts were allocated to the cavalry in 1623, each field regiment consisting of two 175-man squadrons, and, later, to the artillery. Light cavalry was recruited by offering tax exemptions to any farmer willing to provide a fully equipped trooper. A War Board, an embryonic ministry of war, supervised military administration – a much-improved system that produced the largely national army with which Gustav Adolf invaded Germany in 1630. The human implications, however, were considerable. The village of Bygdea in northern Sweden sent 230 young men to fight in Poland and Germany between 1621 and 1639; 215 died overseas and only five returned home, crippled.

Equally important were the tactical innovations devised by Gustav. Many links existed between the Dutch Republic and Sweden – economic, military, naval and diplomatic. When reforming the Dutch Army during the 1590s, Captain- General Prince Maurice of Orange and his cousin, Louis-William of Nassau, had drawn upon the writings of Vegetius, Aelian, Frontinus and Emperor Leo VI of Byzantium as well as the ideas of mathematician Simon Stevin and the philosopher Justus Lipsius. Previously the Dutch Army had assumed the tactical organization of the Spanish, French and Swiss whose pike-and-halberd squares, or tercios, initially of 3,000 men, later reduced to about 1,500, were fringed with arquebusiers. They were essentially defensive formations against which enemies hurled themselves until spent, at which point the tercio counter-attacked. Such formations, although preferred by under-motivated mercenaries, were ill-suited to Dutch bogs and deployed firepower inefficiently, only the arquebusiers facing the enemy being able to use their weapons, whilst most of the pikemen could not participate directly in combat.

Learning from the articulation within the Roman legion, Maurice split the tercios into five-company battalions of 675 men, each combining the pike with the arquebus, later superseded by the matchlock musket. Battalions were arrayed in ten ranks, pikemen in the centre and ‘shot’ to either flank. In theory the arquebusiers could maintain continuous fire, each rank successively discharging its weapons before ‘counter- marching’ to the rear to reload. The pikemen protected the arquebusiers from attack by cavalry: the 16-foot pike out-ranged the cavalry lance, and formed the offensive arm of the battalion in an advance or charge – the ‘push of pike’. In the cauldron of the war with Spain, Maurice forged a system of drill and discipline, reduced his artillery to four basic calibres, reorganized logistics, and, in 1599, equipped the troops with firearms of the same size and calibre. Stevin and the engraver Jacob de Gheyn translated Maurice’s infantry drill into a series of pictorial representations, Wapenhandlingen van roers, musquetten ende spiessen, published in Amsterdam in 1607 and quickly followed by English, German, French and Danish editions. Reinforced by the conquest of Geertruidenberg in 1593 and victory at Nieuport in 1600, the reputation of the ‘Dutch method’ spread rapidly.

Polish armies were rich in cavalry, both heavy horse recruited from the aristocracy and light horsemen from Volhynia and Podolia, their skills honed by constant raiding across the Turkish and Muscovite borders. Polish and Turkish horsemen charged at a fast trot with the lance or sabre. Unable to penetrate tercios bristling with pikes, most West European cavalries, the Swedes included, practised the caracole, in which several ranks of horsemen trotted towards the enemy, discharged their pistols, and retired to the rear to reload while another rank moved forward. Only when the pistol fire had ‘disordered’ the enemy foot did the horsemen close in with the sword. Charles IX of Sweden, who was well informed about Dutch innovations by Jacob de la Gardie, unwisely introduced them into an army of mercenarIes and reluctant conscripts when already fighting Poland during the early stages of a sixty-year conflict. In 1605, at Kirkholm outside Riga, Charles met a small Polish corps commanded by Karl Chodkiewicz, but was uncertain whether to employ the new-fangled tactics or accustomed formations. The Swedish cavalry was initially positioned between the infantry squares but, in response to enemy attacks, was switched to the flanks, where it was charged and broken by lancers. Outflanked and split into three separate bodies, the Swedish infantry suffered 9,000 casualties (82 per cent) as the Polish hussaria and Cossacks penetrated their pike squares: the Poles lost just 100 men. On 4 July 1610 a Russo-Swedish army under Jacob de la Gardie was smashed by the Poles at Klushino while attempting to relieve the siege of Smolensk, only 400 survivors straggling back into Estonia; the remainder of Gardie’s mercenaries joined the victors.

War against the Poles and Prussia (1620-29) was the laboratory for tactical experiment. Gustav Adolf abandoned the caracole and imitated the Poles, training his cavalry to charge at the trot with the sabre. In- addition, sections of musketeers accompanied the horse to disrupt enemy formations by fire prior to the charge. The introduction of the pike and the musket increased the shock and firepower of the infantry. Battalions were thinned from ten ranks to six, with pike in the centre and ‘shot’ on either wing, increasing both the frontage and the volume of fire sufficiently to break up enemy formations and allow the pikemen to attack. The counter-march was employed only when the battalion was engaged at extended range, typically about 100 metres. At close range of 30 to 40 metres, where battles were decided, he introduced ‘volley firing’ by advancing the three rear ranks of musketeers into the intervals between the front three. Volleys were usually delivered as the prelude to a ‘push of pike’. At Breitenfeld in 1631 the Scots Brigade in the Swedish army

ordered themselves in several small battalions, about 6 or 700 in a body, presently now double their ranks, making their files then but 3 deep, the discipline of the King of Sweden being never to march above 6 deep. This done, the foremost rank falling on their knees; the second stooping forward; and the third rank standing right up, and all giving fire together; they powered so much lead at one instant in amongst the enemy’s horse that their ranks were much broken with it. (Robert Monro, Monro his expedition with the worthy Scots regiment call’d Mackays, London 1637)

Alternatively, when within pistol-shot, the first three ranks of musketeers gave a volley, followed by the remainder, before the battalion charged home with pike, sword and musket stock. The emphasis on volley firing, rather than the Dutch rolling fire, rendered musketeers vulnerable while reloading, and dependent upon the pikemen for protection. However, battles were won and lost by furious close- quarter combat and Gustav’s tactics ensured that his men enjoyed maximum advantage when they closed with the enemy.

Further to augment infantry firepower, in 1629 two or three light, 3-pounder cannon – infantry guns – were attached to each battalion: over eighty accompanied the army to Germany in 1630. Pre-packed cartridges increased the rate of fire. Gustav deployed his heavier field guns in mobile batteries. Although Maurice’s and Gustav’s reforms enhanced the efficacy of infantry, the shallow, linear battalions were more vulnerable than the older pike squares to attacks on their rear and flanks. Consequently, battlefield deployment assumed a chequerboard appearance with the spaces between the battalions in the first line covered in echelon by the battalions of the second and, if present, third lines. Cavalry, supported by parties of musketeers, was customarily positioned on the wings where it had the space and freedom to charge before turning against the enemy’s flank or rear.

Gustav, with 18,000 men, renewed the campaign in Livonia in 1621, culminating in the capture of Riga. Employing modern siege techniques acquired from the Dutch – an ability and willingness to dig was another characteristic of the new military discipline – 15,000 Swedes overcame the garrison of 300 regulars and 3,700 militia after a six-day bombardment. With only 3,000 field troops available, the Poles were unable to intervene. Mitau in Kurland was the next target but that was the extent of Swedish achievement; the men were weary, their ranks emaciated by sickness and the constant harrying of the Cossacks. Gustav had also run out of funds. Mitau was lost in November 1622 but Sigismund III Vasa of Poland was in an equally parlous condition, defeated by the Turks in 1621 and no longer in receipt of Danish support, Christian IV being more interested in northern Germany. Sigismund and Gustav were content to sign a truce until 1625.

When hostilities resumed, Gustav quickly overran Livonia north of the Dvina, capturing Mitau and Dorpat, but an expedition into Kurland stalled before Windau and Libau. In January 1626, at the battle of Wallhof, south of Riga, Gustav employed his new tactics to smash the Polish army. The Swedes next invaded and occupied Royal Prussia, a rich province where ‘war could be made to pay for war’. This was imperative because the Livonian campaigns had been financed from Sweden’s own scarce resources. Prussian ports exported Polish grain, and their annual customs income averaged 600,000 riksdaler. In addition, Sweden levied tolls on all ships visiting the southern Baltic ports between Danzig and N arva, the ‘licence system’, which yielded a further 500,000 riksdaler. Taken together, these dues realized more money for Sweden than later French subsidies.

Having subdued Prussia, Gustav struck inland to force Sigismund to make peace. The famous Polish cavalry was overcome by the remodelled Swedish horse at Dirschau on the Vistula in August 1627, but an advance on Warsaw in 1629 was halted at Stuhm (Honigfelde) on 27 June by the Poles, reinforced with 12,000 men from Wallenstein. After failed efforts to negotiate peace in 1627 and 1628, the French, anxious to deploy the Swedish army in Germany to counter the emperor and the Catholic League, brokered a deal in 1629. By the terms of the six-year Truce of Altmark of September 1629, Gustav abandoned most of his Prussian gains but retained the 3 1/2 per cent tolls from the Prussian ports and direct control over Elbing, Braunsberg and Pillau. In 1630 the Duke of Kurland surrendered the customs from his ports of Windau and Libau. In total, Gustav gained 600,000 riksdaler per annum, one-third of Swedish military expenditure.

On 12 January 1628 the Secret Committee of the Riksdag had given Gustav permission to intervene in Germany if necessary. It was invoked on 9 January 1629 because, with the Imperialists on the Baltic coast and Wallenstein constructing a navy at Wismar, there was a possibility that Sweden herself might be invaded. Gustav aimed to drive the Imperialists from the Baltic, restore the pre-1618 political situation in Germany, and establish bases at Stralsund and Wismar through which troops could rapidly deploy should Swedish territory again be endangered. Gustav entered Germany without assurances of foreign aid and uncertain that Denmark would not attack while his back was turned. He did, however, take with him a reformed and battle-hardened army.

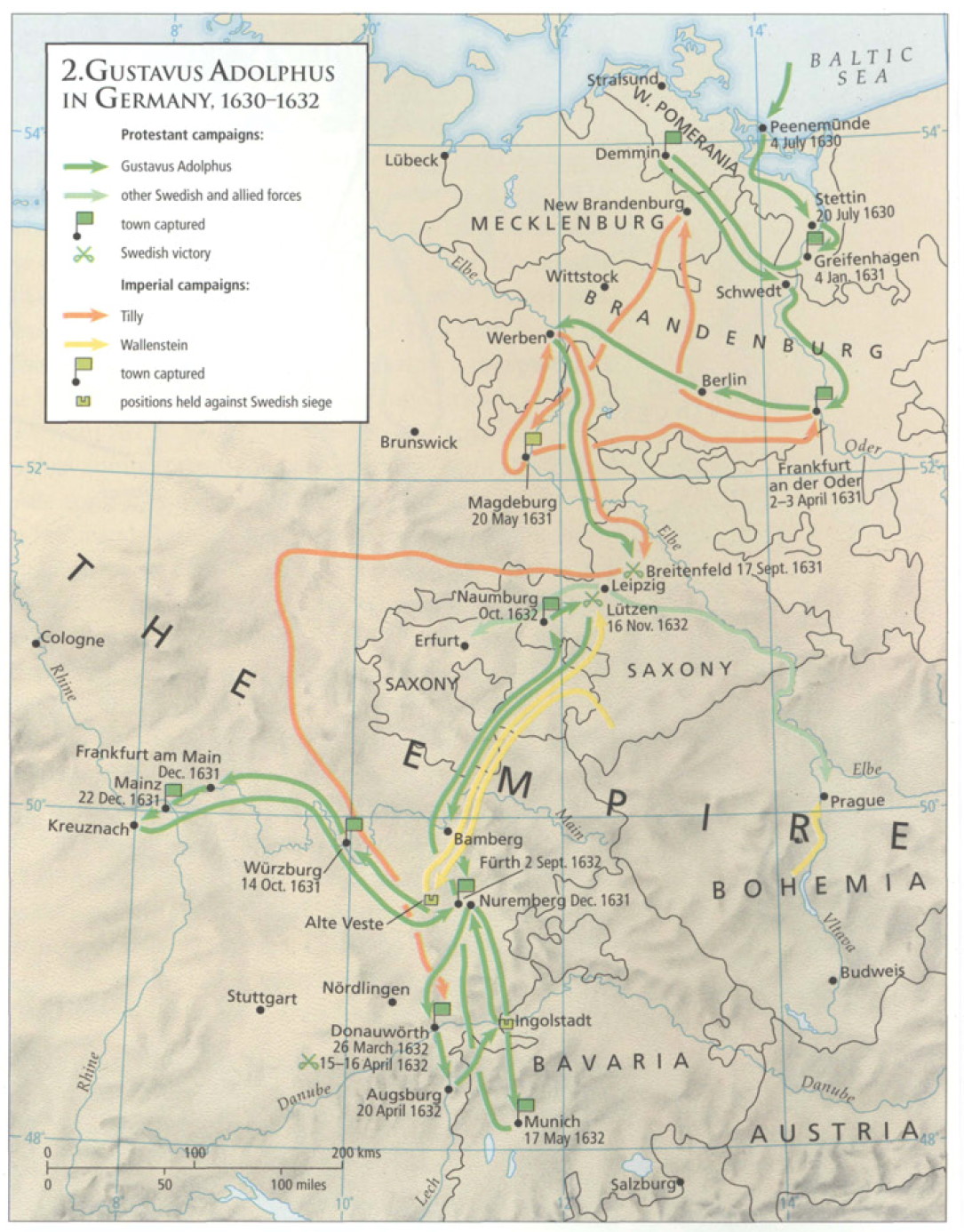

Sailing from Stockholm on 27 June 1630 with 13,000 men packed aboard thirteen transports, escorted by twenty-seven warships, Gustav landed on 6 July at Peenemünde on the northern tip of the island of Usedom in the estuary of the River Oder, whence he probably intended to attack down the line of the Oder into Imperial Silesia, threatening Austria and Vienna. His sole ally was the port of Stralsund, which had withstood an Imperial siege from May to July 1628. Usedom and Stettin were quickly subdued, obliging the Duke of Pomerania to sign an agreement providing the invaders with a larger base area. Only the dispossessed rallied to the Swedish cause, principally the Duke of Mecklenburg and Duke Christian William of Brandenburg (1587-1665), the Protestant ex- administrator of the archbishopric of Magdeburg, who sought to regain the office he had lost following the Edict of Restitution. Magdeburg was a vital post commanding the passage of the Elbe and the routes from Pomerania into Lower Saxony and Thuringia. On 1 August 1630 Magdeburg and Sweden signed an alliance that restored Christian William and inserted a Swedish governor.

Even better was an alliance with Landgrave William V of Hesse-Kassel (r. 1627-37) that gave Gustav a potential opening into Westphalia and the valleys of the Main and Rhine, but for the remainder of 1630 the Swedish army was penned into Pomerania. The major north German princes sat on their hands, especially Electors John George of Saxony and George William of Brandenburg, who were as wary of Gustav as they were of the emperor and Wallenstein. Another problem was supply. Through Stettin and Stralsund Gustav could receive supplies directly from Sweden, but that negated a prime objective. Gustav intended to support his army from German resources, so he needed to expand his beachhead southwards along both banks of the Oder. Eastern Pomerania was cleared, and by Christmas 1630 the ejection of the Imperial garrisons from Gartz and Greifenhagen (Gryfino) opened the lower Oder, but it was not until February 1631 that Gustav succeeded in seizing most of Mecklenburg.

On 23 January 1631 Gustav and his chancellor, Oxenstierna, signed the Treaty of Barwalde with the envoys of France. In return for a subsidy of 400,000 taler per annum over five years, they agreed to field an army of 30,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry but retained freedom of action, Richelieu calculating that any Swedish success would disadvantage the Habsburgs.

Gustav had been able to land unopposed because much of the Imperial Army had been redeployed to northern Italy, where a dispute over the succession to the Duchy of Mantua, ultimately settled in favour of the French candidate, the Duke of Nevers, gave France control of the Grisons and access to northern Italy via Pinerolo. Gustav was also greatly aided by the dismissal of Wallenstein.

At the height of his territorial power, on 28 March 1629 Emperor Ferdinand issued the Edict of Restitution, which restored all Roman Catholic Church property sequestered by the Protestant princes and cities since 1552. In political terms the edict established Imperial-Wittelsbach control over north-western Germany, displeasing Lutheran, Calvinist and Catholic princes. Associated with this was disquiet at the cavalier manner in which the emperor had transferred the Palatinate electorate to Bavaria in 1625 whilst supporters of Denmark – the Dukes of Calenberg, Wolfenbüttel and Mecklenburg – had been dispossessed and their titles and lands given to Imperial generals. Wallenstein rashly accepted the Duchy of Mecklenburg, and Gottfried Pappenheim wanted the dukedom of Wolfenbüttel but was thwarted by Maximilian of Bavaria and had to be content with becoming an Imperial count. Tilly, older and wiser, accepted a gratuity of 400,000 guilders instead of the Duchy of Calenberg.

Aware that Ferdinand’s dominance rested entirely upon Wallenstein’s army and organization, the anti-Imperial princes undermined the generalissimo. His contribution system, which affected friend and enemy alike, was a major grievance, as was his employment of numerous Bohemian Protestants. At the Diet of Regensburg (June to August 1630) the electors made it clear to Ferdinand that they would elect his son, Ferdinand of Hungary, as king of the Romans (i.e. Ferdinand’s successor) only if he sacked Wallenstein, promoted Tilly to command of the Imperial Army, and revoked the Edict of Restitution. Ferdinand had no option but to concede his entire position.

CAMPAIGNING IN GERMANY: GUSTAV VERSUS TILLY

Scattered in winter quarters across Mecklenburg and northern Brandenburg, Tilly’s combined Imperial and Catholic League army was in poor condition, still dependent upon supply, at inflated prices, via the Elbe and Oder from Wallenstein’s Bohemian magazines. In addition, von Arnim, Tilly’s outstanding subordinate, transferred from Imperial to Saxon employment to raise an army for Elector John George. At the end of January 1631 Tilly concentrated his forces before manoeuvring to contain Gustav within his Pomeranian beachhead. During February Gustav seized Mecklenburg. Tilly responded in March by pouncing upon and massacring the Swedish garrison in Neu-Brandenburg. Gustav rapidly assembled his army and marched towards Tilly at Neu-Brandenburg but, although superior in numbers, he hesitated, sought the wisdom of a cautious council of war, and a chance was missed.

This mistake sealed the fate of Magdeburg. Taking the advice of his second- in-command, Pappenheim, at the end of March Tilly upgraded the blockade of Magdeburg into a formal siege, safe in the knowledge that the city was effectively isolated because Gustav could not reach it without violating neutral Electoral Saxony, which he was unlikely to attempt as he could ill afford to antagonize potential allies. Contrary to Swedish expectations, the Imperial siege proceeded quickly and most of Magdeburg’s outworks had fallen by early April. Gustav tried to draw Tilly away from Magdeburg, simultaneously improving his supply and strategic position, by operating against George William of Brandenburg. He struck southwards along the Oder, brushing aside weak garrisons before storming Frankfurt-an-der-Oder on 13 April. Although Gustav’s cause was damaged when unpaid troops vented their frustration upon the Protestant population, the navigation of the Oder had been secured and the Swedes’ eastern flank protected against attack from Poland.

Frankfurt fell too rapidly to distract Tilly from Magdeburg. Gustav now had no choice but to infringe both Saxon and Brandenburg neutrality by taking the direct route over the Elbe bridges at Wittenberg or Dessau. He advanced towards Berlin, but George William would only accept Swedish garrisons in Spandau and Küstrin. Thwarted, Gustav moved to Potsdam and started to bully Elector John George into allowing him to march across Saxony; but it was too late. On 20 May Magdeburg was stormed, looted and burned: out of 20,000 inhabitants, only 5,000 survived. Gustav was in an awkward situation. He had lost his principal ally whilst Saxony and Brandenburg had resisted Swedish pressure. The sole comfort was negative: had Gustav succeeded in marching to Magdeburg he would have encountered superior Imperial forces and probable defeat.

On 11 June 1631 Gustav finally browbeat George William into dividing Brandenburg into ten quartering districts each contributing 30,000 riksdaler per month to the Swedes. Having entered Germany without allies, invitation, or any clear idea of what he was going to do, Gustav was forced by strategic defeat to devise a policy. On the advice of Dr Jakob Steinberg, his adviser on German affairs, Gustav decided to seek victory on the battlefield and then form a league of Protestant states militarily bound to Sweden. Only then could military costs be met from German resources. Tilly, who had intended to use Magdeburg as a base and pivot for his campaign against Gustav, was the proud possessor of a heap of insanitary rubble. Unable to feed his men, he had to move, but his options were limited. Protestant principalities in southern Germany, especially Württemberg and Baden, were arming, and threatened to block the return of Imperial troops from the Mantuan war in northern Ital~ William V of Hesse-Kassel was also preparing to take the field. Hoping to force Tilly to battle before he was reinforced from Italy, Gustav marched west from Brandenburg to cross the Elbe at Tangermünde, bringing him within reach of a new supply area. He then turned north to Werben, south of Wittenberge, where he excavated a fortified camp within a bend in the Elbe. Tilly advanced northwards from Magdeburg but could make no impression on the Swedish field fortifications and lost a cavalry engagement at Burgstall, to the west of Tangermünde. He withdrew on 29 July.

Tilly demanded that John George of Saxony disband his new army, but he refused and opened negotiations with Sweden. Short of supplies, possibly through Wallenstein’s continued awkwardness, on 25 August Tilly invaded Saxony, storming Merseburg and Leipzig. Gustav concluded an agreement with John George on 2 September that added 18,000 Saxons to his 24,000 Swedes. Gustav pushed down the Elbe from his camp at Werben and encountered Tilly’s twenty-seven field guns and 31,000 men on 17 September at Breitenfeld, a village on the northern edge of modern Leipzig. The Imperial infantry were arrayed across Tilly’s centre in seventeen tercios, each fifty files wide and thirty ranks deep, whilst cavalry covered the flanks. The Swedish-Saxon force comprised two separate armies: von Arnim’s 18,000 raw, untried Saxons took the left and the Swedes the centre and right. Both commanders deployed infantry in the centre flanked by cavalry. Unlike the Imperialists and Saxons, the Swedish infantry fought in six-rank, 500-man battalions each supported by a battery of four 3-pounder cannon. In addition, Gustav had fifty-one heavy field guns.

At dawn, amidst artillery salvoes, Pappenheim led forward the Imperial cavalry of the left, but the Swedish horsemen, supported by musketeers from the reserve, held them. In the meantime the Swedish infantry slowly advanced, firing. Tilly then attacked the Saxons and drove them from the field, exposing the Swedish left. General Gustav Horn, exploiting the flexibility and articulation of the battalion organization, formed front to his left flank, ordered reserves from the third line, and launched a vigorous assault on the closely packed tercios before they had time to recover from their exertions against the Saxons. After the Swedish cavalry had finally checked and defeated Pappenheim, who had made seven charges, the infantry, directed by Horn and Báner, advanced to crush the Imperial foot in a melee of musketry, cannon fire and hand-to-hand combat: 7,600 Imperialists were killed, 9,000 wounded or taken prisoner, and 4,000 deserted. Most of the prisoners ‘accepted’ immediate service in the Swedish Army.

Tilly, wounded, withdrew north-west, covered by Pappenheim. Three strategic choices opened before Gustav. He could advance on Vienna through Silesia; pursue Tilly into the Lower Saxon Circle; or march to the fertile lands of the Rhine and the Main in search of supplies and contributions. From necessity he selected the latter, leaving von Arnim and the Saxon army to campaign into Silesia and Bohemia, capturing Prague on 1S November 1631. Gustav reached Erfurt on 22 September, a major road junction in Thuringia whence he commanded extensive supply areas for an army already engorged as mercenaries flocked to a successful leader, and threatened Tilly’s communications with his principal bases in Bavaria. By early October Gustav had reached the upper Main, seizing Würzburg on 4 October and its citadel, the Marienburg fortress, three days later. Meanwhile, Tilly had scraped together the Imperial garrisons in north Germany, collected stragglers, and effected a junction with the corps of Charles IV of Lorraine, a member of the Catholic League. Tilly marched south, feinted towards Gustav at Wiirzburg, then continued into winter quarters around Ingolstadt, the Danube fortress guarding the northern frontier of Bavaria. With Tilly removed, Gustav resumed his march, entering Frankfurt-am-Main on 17 November, Worms on 7 December, and Mainz on 12 December. The Elector- Archbishop of Mainz fled, along with the Bishop of Würzburg, whilst the Elector-Archbishops of Trier and Cologne appealed to France for protection. Richelieu was happy to oblige and placed French garrisons in the Trier fortresses of Ehrenbreitstein and Philippsburg, thus denying the line of the Moselle to Sweden and establishing a French military presence on the Rhine. In one campaign Gustav had marched from the estuary of the Oder to the Middle Rhine, defeated the fearsome Tilly, expanded his army, and placed his logistics on an improved footing. Extreme good fortune plus astute operations had made Gustav the dominant force in Germany.

Any opportunity to make trouble for Poland was impossible to resist, but Gustav was content merely to assist Tsar Mikhail Romanov of Muscovy (r. 1613–45). Gustav gave him permission to recruit troops in the Swedish-controlled portions of Germany, the Scottish mercenary Alexander Leslie raising 5,000 men in 1632. The Russian attack on Smolensk was unsuccessful and peace between Poland and Russia was signed at Polyanovka in June 1634. In 1635 French agents brokered a truce at Stuhmsdorf that kept the Poles and the Swedes from each other’s throats for twenty years: Poland ceded Livonia to Sweden whilst the latter evacuated the Prussian ports, their tolls having been replaced by German revenues.

By Christmas 1631 Sweden ruled half Germany. Early in 1632 Oxenstierna arrived at Mainz from Prussia, where he had been governor, to administer the conquered territories. Over the winter Gustav recruited another 108,000 men to bring his total forces in Germany to 210,000. Such extravagance could not be long supported so a rapid end to hostilities was imperative.

Sweden’s German ’empire’ was a tenuous affair. Pomerania and Mecklenburg were connected to the main base at Mainz via a corridor through Thuringia controlled by the fortress of Erfurt, garrisoned by one of eight field armies. Another four armies, numbering 30,000 men, faced Pappenheim, who was operating from Hameln on the Weser against the western edges of Thuringia. Should Pappenheim sever the Erfurt corridor, Gustav’s communications with the Baltic ports and Stockholm, plus the flow of supplies and money from north Germany, would be interrupted. However, the cause of the Imperialists and the Catholic League had collapsed: Sweden threatened Bavaria and occupied Würzburg, Mainz and Bamberg; France controlled Lorraine, Trier and Cologne; the Dutch had captured the Spanish treasure fleet off Cuba in 1628 and attacked Brazil in 1624-5 and 1630; and the fortresses of ‘s-Hertogenbosch and Wesel had been lost to Prince Frederick Henry of Orange.

THE RETURN OF WALLENSTEIN

In extremis, on 5 December 1631 Emperor Ferdinand reinstated Wallenstein. From his bases in Bohemia he rapidly raised 70,000 men and stood ready to advance against Electoral Saxony, Silesia and Thuringia but was restrained by von Arnim’s army in and around Prague.

Returning to the field in March 1632, Gustav marched with 37,000 men from Nuremberg to Donauwörth, where he crossed the Danube intent upon crushing Tilly before moving on Vienna via Bavaria and Austria. Maximilian of Bavaria joined Tilly at Ingolstadt, but their combined army numbered only 22,000 men. Gustav could not afford to waste time and so, on 5 April, under cover of smokescreens, diversionary attacks and an artillery barrage, he threw a pontoon bridge over the Lech and forced a crossing. Carrying the mortally wounded Tilly, the Imperial-Bavarian army withdrew to the modern fortress of Ingolstadt whilst Gustav marched south down the Lech to Augsburg, which was forced to pay a monthly contribution of 20,000 riksdaler. While Maximilian was penned into Ingolstadt on the north bank of the Danube, Gustav devastated Bavaria, thereby augmenting his own supplies whilst denying them to Maximilian.

Having raped the country, Gustav intended to march east to Regensburg but Maximilian, leaving a strong garrison in Ingolstadt, slipped away and occupied the city: Gustav had anticipated that Wallenstein would march into Bavaria to relieve the pressure on Maximilian, but Wallenstein showed no sign of leaving Bohemia and thus maintained the threat to Saxony and Thuringia. A fleeting possibility of help for the Catholic League and the emperor occurred when the Spanish Army of the Netherlands took Speyer and a few places along the Lower Rhine in order to reopen the Spanish Road and protect it against Swedish depredations. However, in June the Dutch Army captured Venlo, Roermond, Straelen and Sittard, obliging Spain to recall her troops from the Palatinate.

Even worse, the Dutch then laid siege to the vital fortress of Maastricht, which commanded communications between the Spanish Netherlands and Westphalia. Despite an attack on the Dutch siege works by an Imperial relief army under Pappenheim, Maastricht fell on 23 August 1632. No assistance could be expected from Italy, where an epidemic of plague ravaged the northern provinces.

Gustav decided to secure Swabia as a forward base and supply area. Accordingly, having captured and thoroughly plundered Maximilian’s capital of Munich, he marched west to Memmingen as a preliminary to turning towards Lake Constance. On 25 May 1632, while at Memmingen, he received intelligence that von Arnim had evacuated Prague on 15 May and was retreating from Bohemia, leaving Wallenstein free to manoeuvre against Saxony and the Erfurt corridor. On 4 June 1632 Gustav marched for Nuremberg, a rich city untouched by war, with 18,500 men, leaving the rest of his army to guard the Bavarian conquests and Swabian base. Gustav built a fortified camp abutting the modern fortifications, the ‘Nuremberg Leaguer’, flanking any advance by Wallenstein into Saxony. In reply, Wallenstein joined with Maximilian’s army, bringing his total forces to 48,000 men, before marching north to build his own fortified camp at Zirndorf, just west of Nuremberg, to interfere with Swedish supplies from Bavaria and Swabia. Gustav and Oxenstierna summoned to Nuremberg all troops that could be spared from other sectors, enabling the Swedes to interdict Wallenstein’s supply lines from Bohemia.

Gustav’s supply situation was more critical, and he sought to solve the tactical conundrum by battle. The Imperial position stretched north-south along a ridge parallel to the River Rednitz. It could not be attacked from the east as Wallenstein’s artillery covered all crossing-points. From the south and west the country was more hospitable but entirely lacked roads capable of supporting artillery. To the north the ridge rose to a hill, the Alte Feste, which lay just outside the perimeter of Wallenstein’s camp, before tumbling in rocky slopes and thick woodland towards the town of Fürth. On the night of 22/23 August Gustav moved his command to Fürth, but Wallenstein anticipated his move and drew up his whole army in line of battle on the northern edge of his leaguer. Thinking that Wallenstein was withdrawing westwards and that he faced only a rearguard, early on 24 August 1632 Gustav sent his cavalry to interfere with Wallenstein’s supposed retreat and launched his infantry against the Alte Feste. All day the Swedish infantry sweated up the steep slopes, but they were unable to develop their full firepower because the infantry guns could not be deployed. Despite sacrificing 2,400 men, the Swedes failed to take the Alte Feste; Wallenstein lost only 600. The myth of Swedish invincibility was severely dented.

Back at Fürth, supplies ran low, disease broke out, and within two weeks one- third of Gustav’s fickle mercenaries had deserted. Leaving Oxenstierna to hold Nuremberg, he marched on 8 September uncertain of the next move. Wallenstein had won the war of position.

Gustav crossed the Danube into Swabia on 26 September and then threatened Ingolstadt, but neither operation was sufficient to deflect Wallenstein, who was preparing to unite with Pappenheim, crush the Swedes in the Lower Saxon Circle, and then overwhelm John George of Saxony. On 10 October at Nordlingen Gustav received intelligence that Pappenheim and Wallenstein were still separated, Maximilian was returning to Ingolstadt, and the corps of Generals Holck and Gallas had been detached from Wallenstein’s main arm~ There was a chance for Gustav to exploit Wallenstein’s imbalance. A week later, after learning that Wallenstein had invaded Saxony – Leipzig fell on 1 November – he covered 630 kilometres in seventeen days to secure the Thuringian passes before Pappenheim.

Despite his speed, Gustav would have been too late had not Bernard of Saxe-Weimar moved his army into the area and stood firm until Gustav joined him at Arnstadt, south of Erfurt. Another dash to the north-east by the combined armies of Gustav and Bernard guaranteed the crossing of the Saale at Naumburg, where Gustav built a fortified camp within a bend of the river. Wallenstein approached, but after hovering for a fortnight decided that the Swedes had taken winter quarters. Accordingly, on 14 November he dispersed his forces into seasonal billets suitably located to enable his men to cut Gustav’s communications and ruin his supply areas. Pappenheim’s corps of nine regiments was dispatched to Halle, 30 kilometres to the north.

Wallenstein had misread Swedish intentions. Gustav marched from Naumburg on 16 November to attack Wallenstein’s headquarters at Lützen, 27 kilometres distant to the north-east and 9 kilometres south-west of Leipzig. When crossing the River Rippach he skirmished with an Imperial detachment, which both delayed his advance and gave Wallenstein sufficient notice to summon his dispersing forces to march on Lützen.

Wallenstein could recover only about 19,000 men to face a similar number of Swedes. Pappenheim received Wallenstein’s recall order at Halle around midnight on 16 November, and although he marched immediately with his cavalry, leaving the infantry to follow six hours later, he was not expected on the battlefield before midday. Fixing his right on a line of windmills near Lützen Castle and village, Wallenstein extended his centre along the foot of a valley behind a sunken road and ditch which he lined with musketeers, but his left was unanchored, awaiting the arrival of Pappenheim. To his rear, Wallenstein formed his baggage and supply train into a ‘wagon-laager’, a line of heavy wagons linked by iron chains, a tactical device perfected by the Hussites and much used on the Polish and Ukrainian steppes. Not only did this constitute a final line of defence for his infantry, but it caused uncertain mercenaries to think twice before quitting the field. Wallenstein learned quickly: no longer was his infantry arrayed in tercios but in Swedish-style battalions.

Appreciating the weakness in the Imperial position, the Swedish army was ready to attack at 7 a. m. but fog was slow to clear and operations did not begin until 11 a. m. Although he had been denied four vital hours, it was still possible for Gustav to snatch a rapid victory. His foot advanced across the sunken road and ditch to fix the Imperial infantry while Gustav’s right began to envelop Wallenstein’s unsupported left. Progress was encouraging until, about noon, Pappenheim appeared with his cavalry and immediately launched an attack to restore the situation on Wallenstein’s left. Pappenheim fell, struck by a cannon ball early in the attack, and an Imperial regiment deserted: signs of panic were evident in the disintegrating Imperial left, and the Swedish centre pressed forward and captured seven of Wallenstein’s cannon.

The battle was virtually over when fog descended, hiding the chaos on the Imperial left, leaving Gustav unaware of the propinquity of complete victory. The Swedish attack on Lützen village on the Imperial right, the strongest section of their line, stalled, and Gustav led forward the Smaland cavalry regiment to inject momentum. Gustav was shot three times, fatally, and command of the army passed to Bernard of Saxe-Weimar. Ottavio Piccolomini led his cuirassiers against the Swedish right in a series of vigorous charges that threatened to become overwhelming but the Swedish centre held on the far side of the road and ditch, assisted by a battery of heavy field guns in the middle of the line, while the left worked forward to capture the Lützen windmills.

By dusk at 5 p. m. the keys to Wallenstein’s position had fallen, all his cannon were lost, and only hard fighting by the Imperial infantry prevented a Swedish breakthrough. Pappenheim’s infantry arrived around midnight but Wallenstein had already decided to abandon the field. He had lost over half his army; the Swedes about one-third.

Even in 1630, mercenaries had comprised half the Swedish Army, although they were mostly deployed in Livonia, leaving the native conscripts to sail for Germany. By 1631 three-quarters of the Swedish army in Germany was mercenary, and in 1632, when Gustav’s total forces in Germany had reached 150,000, nine-tenths. Lützen and the Alte Feste ruined the native army. The domestic conscription system functioned erratically, whilst the German replacements and mercenaries could not deliver the high standards of drill and discipline required to implement Gustav’s tactics. After 1632 Sweden’s military edge was blunted.

Money was also a persistent problem. In peacetime, native Swedish levies drew their wages from the farms where they were based, the farmer deducting that sum from his taxes. In wartime, the king paid his native soldiers only a small monetary wage, the balance coming from contributions levied upon occupied territories. Mercenaries had to be paid either directly from the Swedish treasury or, preferably, also out of contributions. From the landing at Peenemünde, this issue, plus its close relative, supply, dominated Swedish policy and decision- making. Gustav’s death made possible a political settlement in Germany, but the cost of demobilizing the Swedish Army and its numerous contractors was too high for the princes, both Catholic and Protestant, to accept.

Although he forced 8,000 Swedish troops under the Bohemian Count Thurn to surrender at Steinau in Silesia on 10 October 1633, Wallenstein had outstayed his rehabilitation. Mistrusted by Emperor Ferdinand, who strongly suspected that he was using the Imperial Army to pursue his own, private agenda in Germany, Wallenstein was murdered by Scottish, Irish and English mercenary officers in the Bohemian frontier fortress of Eger on 25 February 1634.

Ferdinand then summoned his son, Ferdinand of Hungary, the future Emperor Ferdinand III, to command the Imperial armies, but actual control rested with Gallas, who was rewarded with Wallenstein’s duchy of Friedland. In 1634 Sweden and Saxony launched a double-pronged offensive. Von Arnim and the Saxons invaded Silesia and Bohemia, arriving again beneath the walls of Prague. In the meantime, the army of Sweden and the League of Heilbronn, principally Brandenburg plus the Swabian, Franconian, Upper Rhenish and Electoral Rhenish Circles, commanded by Gustav Horn and Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, attacked Bavaria. The fortress of Landshut, north-east of Munich, was captured and Johann von Aldringen (1588-1634), a Luxembourger who succeeded Tilly in command of the Catholic League-Bavarian army, killed. However, Ferdinand of Hungary recaptured Donauwörth and Regensburg during July, thus re- establishing communications between Bavaria and the Habsburg lands in Austria. Von Arnim withdrew from before Prague, and on 30 July Ferdinand besieged the Protestant city of Nördlingen and awaited the arrival of the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria (1609-41), governor of the Spanish Netherlands, who was marching with 15,000 Spanish troops from northern Italy. The two Ferdinands united on 2 September, before the arrival of the Swedes under Horn and Bernard, and constructed a fortified camp in the hills south of Nördlingen. They had 35,000 men, whereas the Swedes, who had been obliged to send substantial reinforcements into Poland following Russia’s withdrawal from the War of Smolensk, had 10,000 fewer.

In the two-day battle of Nördlingen (5-6 September 1634) the Swedes were badly beaten, losing 12,000 casualties, of which 4,000 were prisoners including Horn. Bernard led the remnants into Alsace. The Swedish position in Germany collapsed – all garrisons south of the Main were abandoned, the Heilbronn League disintegrated – but the most important outcome was that France could no longer hide behind Sweden. A Spanish attack on French-garrisoned Trier spurred Richelieu to declare war on Spain on 19 May 1635. Anxious for reconciliation, Bavaria, Saxony, Brandenburg, Mainz, Cologne, Hesse-Darmstadt, Mecklenburg, Trier, Lubeck, Frankfurt-am-Main and Ulm signed the Peace of Prague with the emperor. Under the terms of the peace, all the princely armed forces were gathered into a single Imperial Army – the electors would continue to command their own contingents but only as Imperial generals – the Edict of Restitution was suspended for forty years, alliances between princes of the empire were forbidden, and the supremacy of the emperor was recognized. In August 1635 unpaid mutinous soldiers in Swedish service held Oxenstierna hostage in Magdeburg and released him only when promised that arrears would be met from Sweden herself if money could not be prised out of Germany. France’s war against Spain diverted Habsburg resources from northern Germany and allowed Sweden to recover.

Richelieu allied with the Dutch Republic, Savoy, Mantua and Parma. Between 1634 and 1636 the French Army contained about 9,500 horse and 115,000 foot, divided amongst field armies in the Spanish Netherlands, northern Italy, Lorraine and Franche-Comte, but there were insufficient troops to meet commitments in Germany. This hole was plugged by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, who agreed to leave Swedish service and maintain an army of 18,000 men for France in Germany at an annual cost of 1,600,000 taler. Wastage was considerable. Of the 26,000 French soldiers consigned to the Spanish Netherlands in 1635, only 8,000 remained at the end of the campaign.

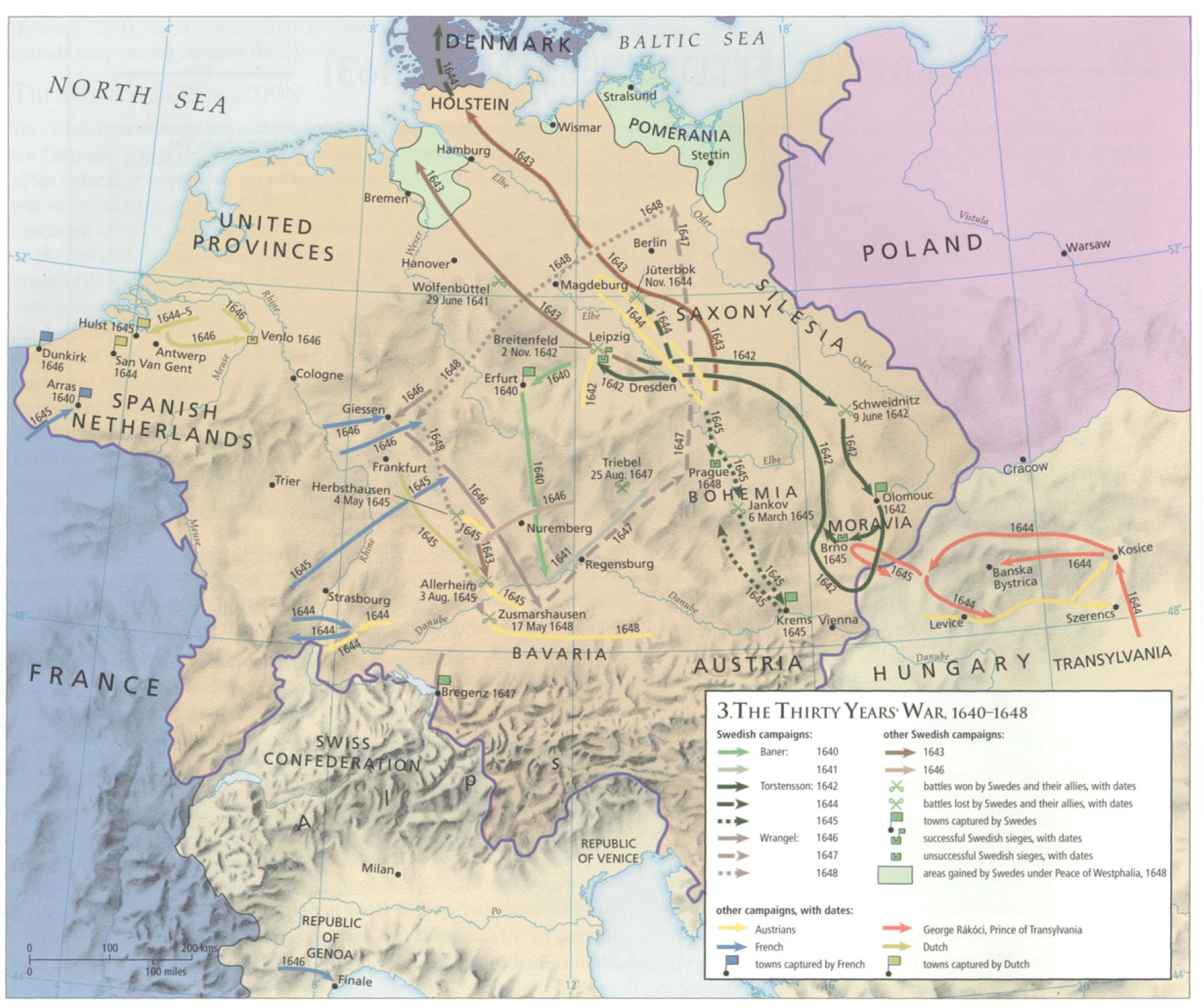

Between November and December 1635, Báner, commander of the Swedish army in Germany, and Lennart Torstensson, the artillery commander, beat the Saxons in a series of actions preparatory to striking down the Elbe and Saale towards Naumburg in the spring. Spain replied with an offensive against France in the summer of 1636 during which Gallas invaded Lorraine and Franche- Comte. Piccolomini, with troops from the Spanish Netherlands, was halted only at Corbie on the Somme, a mere 130 kilometres from Paris.

On 4 October 1636 a combined Imperial-Saxon army of 25,000 men under Hatzfeld intercepted Báner and Torstensson, with about 18,000 soldiers, in wooded hills south of Wittstock in Brandenburg, 93 kilometres north-west of Berlin. Báner dispatched half his force on an 11-kilometre flank march against the enemy’s rear, while with the remainder he seized and held a hill before the enemy’s line in order to pin them in position. Although outnumbered by fifty squadrons to seventeen, the Swedish cavalry resisted the Imperialists from mid-afternoon until sunset, at which point the pressure was relieved when the flanking corps struck the Imperial-Saxon army in its rear and flank. Assaulted from three sides, the Imperial-Saxon troops collapsed and fled. In a vigorous pursuit on the following day the Imperial-Saxon army was destroyed and Sweden regained control of Pomerania, Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia. In January 1637 Báner advanced to besiege Leipzig but was repulsed, and Imperial and Saxon forces under Gallas drove him back to Pomerania where, short of both money and supplies, the Swedish army then cowered for over twelve months.

Gallas’s pursuit of Báner gave Bernard of Saxe-Weimar an opportunity in south-west Germany. Marching east along the Rhine from his winter quarters around Basel, Bernard attacked a Bavarian-Imperial army at Rheinfelden in Swabia and exploited his victory by taking the fortresses of Rheinfelden, Neuenburg and Freiburg-im-Breisgau, before besieging Breisach, a key post on the Spanish Road (June to December 1638). Master of Alsace, Bernard then sought to consolidate his gains into a personal duchy but he died of smallpox on 18 July 1639 before reaching agreement with Richelieu. His Bernese lieutenant general, Hans Ludwig von Erlach (1595-1650), promptly sold Bernard’s Alsatian possessions to France, thereby improving Richelieu’s strategic position. Like Bernard, Báner probably dreamed of acquiring a German principality but died in 1641 before realizing this ambition.

CONTINUING DEVASTATION

The war in Germany was losing political direction. Armies campaigned simply to conquer territory and levy contributions sufficient to support themselves and aggrandize their commanders. The adage of Gustav and Richelieu that ‘war must pay for war’ had mutated to ‘war is the purpose of war’. Desperately searching for money and food for their largely mercenary forces, Swedish commanders often acted on their own initiative, ignoring the instructions of Oxenstierna, whose authority diminished substantially after Queen Christina achieved her majority in 1644. During this period the most extensive destruction and depredation occurred. The ravagings by Tilly, Wallenstein and Gustav had stripped large stretches of Bavaria, north Germany and the Rhine valley of supplies and population, but at least the contribution system imposed some kind of order on military demands. After the mid-1630s depredation became an end in itself, with all soldiers struggling for a share of what remained of German resources. Garrisons, some Brobdingnagian, many Lilliputian, dotted across the country did most of the damage because each depended for supplies upon dominating its local hinterland; incursions by large armies were relatively infrequent and were possible only through less ravaged regions. To add to these burdens, all states demanded greatly increased taxation to meet escalating military costs.

Historians have long debated the actual extent of the destruction visited upon Germany by the war: by any criteria, it was enormous. Perhaps one-quarter of the pre-war population of around 20 million people was lost, most to epidemics spread by armies and malnutrition, although numbers emigrated into Poland, Denmark, France, Switzerland and Italy. Bohemia had 3,000 fewer villages in 1648 than in 1618; Mecklenburg’s 3,000 cultivated farms had been reduced to just 360 by 1640; Württemberg, occupied by Imperial and Bavarian troops between 1634 and 1638, had 450,000 inhabitants in 1620 but just 100,000 in 1639.

Not everyone suffered. Hamburg enjoyed a good war, benefiting from trade redirected from other ports, whilst Amsterdam grew rich on the Baltic grain trade and arms manufacture.

Torstensson led the Swedish army out of Pomerania to campaign deep in the Habsburg heartlands of Bohemia, Silesia and Moravia. During the spring of 1642 he marched through Saxony into Silesia, defeating John George’s army at Schweidnitz, before entering Moravia, capturing the capital, Olmütz, in June. Vienna was threatened but Torstensson retired to besiege Leipzig: Emperor Ferdinand Ill’s brother, the Archduke Leopold, and Piccolomini hurried to its relief. Torstensson withdrew a little to the north and offered battle at Breitenfeld where he repeated Gustav’s earlier success. The Imperialists lost 10,000 men, forty-six cannon and their supply train, plus the archduke’s treasury and chancery. Leipzig fell in December, remaining in Swedish possession until 1650. Breitenfeld was the last in a series of Habsburg disasters: Breda had fallen to the Dutch in 1637, who also destroyed two Spanish fleets during 1639, one in the Downs and the other off Recife; in 1640 Catalonia rebelled, aided by the French, and Portugal declared its independence from Spain, beginning a war that was to run until 1668. Arras and Artois were lost to France in 1640; Salces and Perpignan in 1642.

France was principally concerned with Spain. In the spring of 1643 Don Francisco de Melo, governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands from 1641 to 1644, encouraged by news of Richelieu’s demise, invaded France. Crossing the border with 19,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry, he besieged the small fortress of Rocroi, which commanded the confluence of two routes to Paris, one through Reims, the other via Soissons. The French government sent a relief force of 17,000 foot and 6,000 horse under the 22-year-old Conde. The approach on the Reims road ran through a wooded defile, but Conde’s passage on 18 May was uncontested and the armies drew up in line of battle on the plateau to the south of the town, Melo’s army depleted by the forces he was obliged to leave in the siege works around Rocroi. Both armies deployed their infantry in two lines, staggered so that the tercios in the second line covered the spaces in the first, with cavalry on the flanks, but Conde had sufficient troops to enable him to form a third, reserve line comprising horse and foot. Probably this was intended to cover the anticipated arrival of 6,000 Spanish reinforcements.

At dawn on 19 May Conde launched cavalry attacks to either flank. On the right the French swept away the Duke of Albuquerque’s horse and turned to attack the Spanish infantry in the flank, but the reverse occurred on the left, where the Spaniards proceeded to drive in the exposed wing of the French foot. Intervention by Conde’s reserve prevented collapse but the situation was not stabilized until Conde brought his successful cavalry around the rear of the Spanish army and assaulted the attacking forces from behind.

Having thus defeated the Spanish cavalry, Conde concentrated on the infantry: Musketeers and artillery opened gaps in the tercios that were then exploited by the horsemen. After three assaults the Spaniards surrendered. Conde lost 4,000 men: Melo suffered 7,000 casualties, whilst 8,000 of his men were taken prisoner.

As the Habsburg cause declined, Sweden turned from Germany to deal with Christian IV of Denmark. Early in 1643 the Swedish royal council decided to end Denmark’s intrigues and machinations by depriving her of control over the Sound and the provinces of Scania, Halland and Blekinge. In December Torstensson and the Brandenburg general Hans Christoff Konigsmarck (1605-63) marched the Swedish army from Bohemia to the southern border of Jutland, from where Konigsmarck overran the secularized bishoprics of Bremen and Verden while Torstensson invaded Holstein.

Early in 1644 Torstensson commenced the conquest of Jutland, a process that took only two months. Operating on the Scandinavian peninsula during February 1644, a second army under Horn occupied all of Scania except for Malmo and Kristianstad. Fifteen out of seventeen men-of-war in the Danish Navy were lost to the Swedes off the island of Femern in October 1644 and, although Torstensson temporarily abandoned Jutland because of supply problems, his lieutenant, Karl Wrangel, later reoccupied it and, in conjunction with a landing on the Danish islands, forced Christian to make peace. By the Treaty of Bromsebro of 1645, Sweden retained Halland for thirty years and took outright possession of Gotland and Oesel plus the Norwegian provinces of Jamtland and Harjedalen.