The Birth of the Ilmavoimat

Farman HF.XVI Maritime recon a/c -1915

Finland was part of the Russian empire from 1809 until the

Russian Revolution in 1917 and the first steps in Finnish aviation were taken

with Russian aircraft. The first Finnish pilots were trained in Russia in the

Imperial Army and the Russian military had a number of aircraft stationed in

the country during WW1 as part of the Air Arm of the Imperial Russian Baltic

Fleet, with Military Air Stations in Ahvenanmaa, Turku and Helsinki. Aircraft

flown were Farman HF.XVI Maritime recon a/c -1915, Farman MF.11 Maritime recon

a/c -1916, Schetinin M-9 Maritime a/c -1917, Schetinin M-16 Maritime recon a/c

-1917 and Schetinin M-5 Trainer a/c -1917.

The Maurice Farman MF.11 Shorthorn was a French

reconnaissance and light bomber biplane developed during World War I by the

Farman Aviation Works. It was essentially a Farman MF.7 with a more powerful

engine, and a more robust and aerodynamic fuselage, which was raised above the

lower wing on struts.

Farman MF.11 Maritime recon a/c -1916

The aircraft was also fitted with a machine gun for the

observer, whose position was changed from the rear seat to the front in order

to give a clear field of fire. Its name derived from that of the MF.7 Longhorn,

as it lacked the characteristic front-mounted elevator and elongated skids of its

predecessor. Its maximum speed was 66mph (106kmph), it could reach an altitude

of 12,000 feet and had an endurance of 3.75 hours. Interestingly enough, at the

beginning of World War I, Russia had an air force second only to France,

although a significant part of the Imperial Russian Air Force used outdated

French aircraft of which the Farman’s were some. The Imperial Russian Air Force

used large numbers of seaplanes, but at least in the Gulf of Finland, the bases

in Finland were subsidiary to the large seaplane base in Reval (Tallinn). The

Imperial Russian Air Force aircraft hangars for seaplanes in Reval (Tallinn)

harbor were some of the first reinforced concrete structures in the world.

The seaplane hangars were designed by a Danish company

Christiani & Nielsen (project manager Herluf Trolle Forchhammer and

constructor Sven Schulz) and it comprised of three shell concrete domes with a

general plan of 50×100 meters. On June 9th, 1916 the same company, Christiani

& Nielsen was also given the task of constructing the hangars. The actual

construction commenced on July 5th, 1916.

These reinforced concrete seaplane hangars, begun in 1912,

are undoubtedly one of Europe’s most remarkable aviation monuments. Their

pioneering shell structure matched their use for a pioneering 20th century

activity, powered flight. Their survival up to the present day is equally

remarkable. The Hangers have been the object of an exemplary and technically

complex restoration of the structure when it seemed beyond all hope of repair. Sheltering

a popular maritime museum today, the restored seaplane hangars also play a part

in the regeneration of a hitherto run-down neighbourhood of the Estonian

capital.

The hangars at the Tallinn Seaplane Harbour are the most

important engineering landmark in the region. They are thought to be the first

large-scale reinforced concrete shell structure in the world. When the hangars

were first built, The Builder, a British architectural journal, compared them

with Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. In the Soviet period, the seaplane harbour was

in the hands of the military and the neglected hangars were decaying rapidly.

By the time the restoration work began in 2009, the building was in terrible

disrepair and on the verge of collapsing. Quick action carried out by an

experienced team helped to save and refurbish the structure. In 2010- 2012, the

seaplane harbour was renovated as a maritime museum which opened in May 2012.

It has since become Tallinn’s most visited attraction after the Old Town and

the most visited museum in Estonia. (See the Lennusadam Seaplane Harbour

Museum’s website).

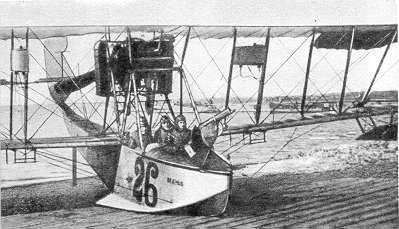

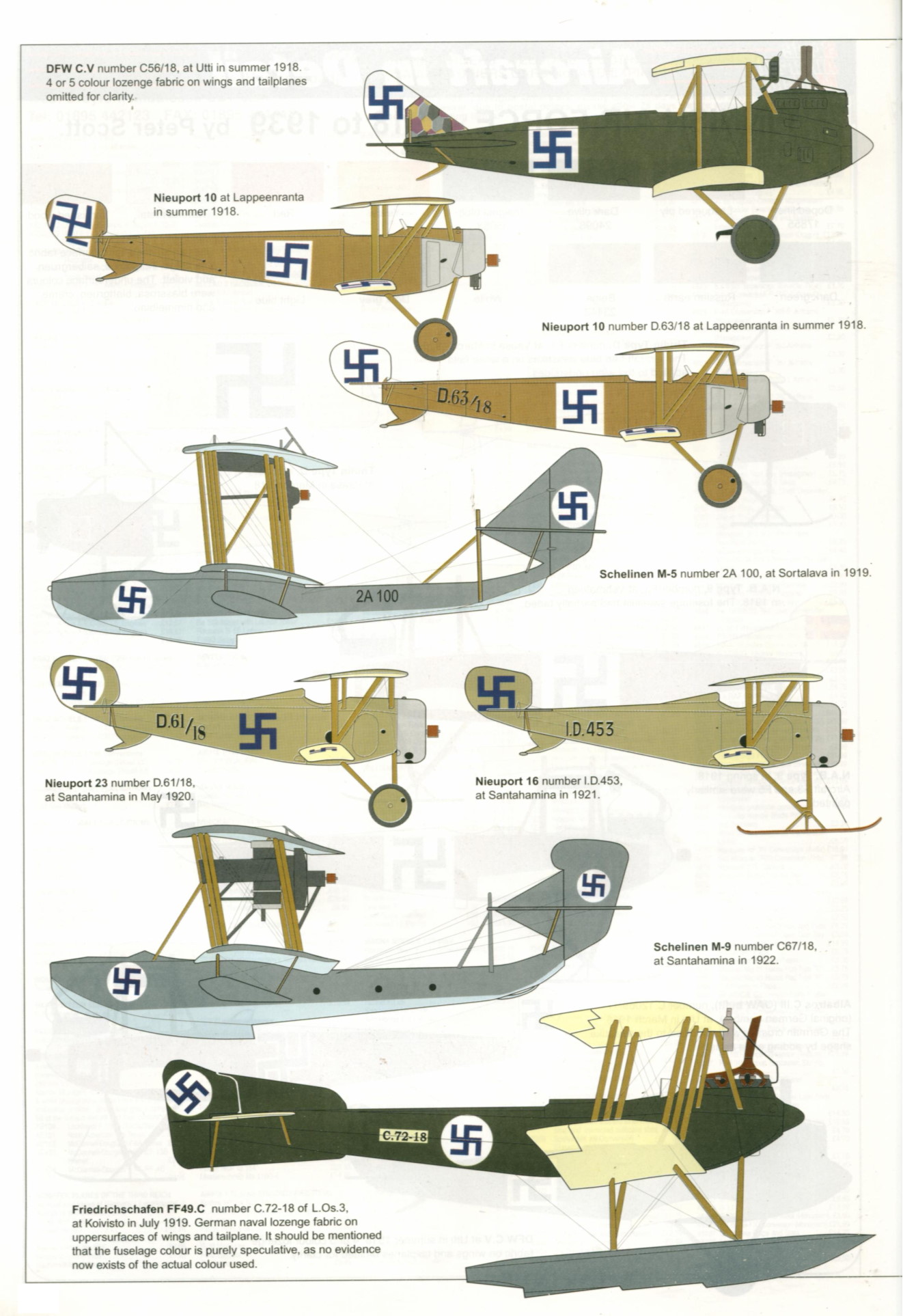

Shchetinin M-9 Maritime a/c -1917 – those captured by the

Whites in the Civil War were later used by the Ilmavoimat as a Primary Trainers

The Grigorovich M-9 (alternative designation ShCh M-9,

sometimes also known as the Shchetinin M-9) was a Russian World War I-era

biplane flying boat, developed from the M-5 by Grigorovich. The first M-9 was

ready in 1915 and its maiden flight was carried out on January 9, 1916 at Baku.

On September 17, 1916, the test pilot Jan Nagórski became the first to make a

loop with a flying boat. During the Russian Civil War, M-9s participated in the

air defence of Baku, dropping approximately 6,000 kg of bombs and 160 kg of

arrows. The aircraft also carried out photo reconnaissance, artillery spotting

and air combat sorties. The M-9 was also used for the first experiments on sea

shelf study, participating in the finding of new oil fields near Baku. Nine

M-9’s were captured by Finland during the Russian Civil War. One was flown by a

Russian officer to Antrea on April 10, 1918. It sank the following day during

type evaluation. Eight more were taken over at the airfields at Åland and

Turku. The aircraft were used until 1922 by the Finnish Air Force.

The Grigorovich M-9 (alternative designation ShCh M-9,

sometimes also known as the Shchetinin M-9)

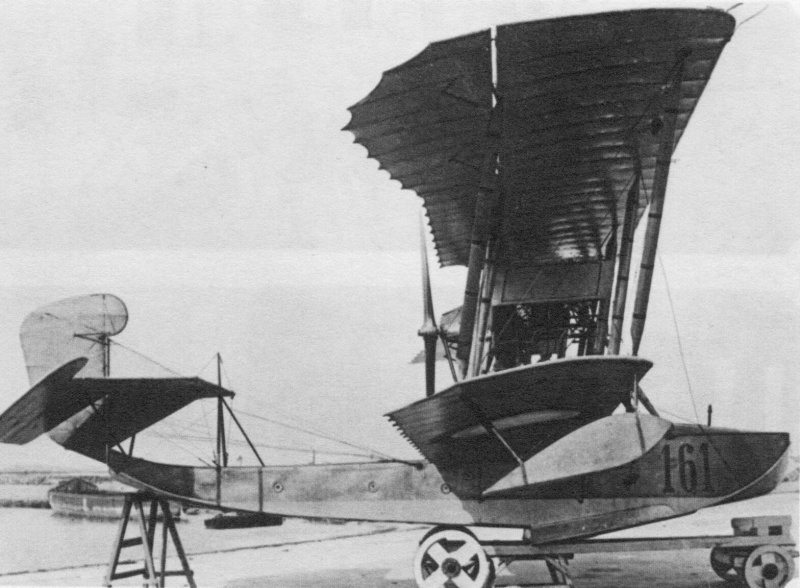

The Grigorovich M-16 (alternative designation ShCh M-16,

sometimes also known as the Shchetinin, Schetinin or Stetinin M-16) was a

successful Russian World War I-era biplane flying boat of the Farman type,

developed from the M-9 by Grigorovich. The M-16 was a version especially

intended for winter operations, with better aerodynamic qualities. It was

somewhat larger than the M-9. Six M-16s fell into Finnish hands during the

Russian Civil War. The first Finnish parachute jump was done on June 17, 1922

from an M-16 by a parachuter named E. Erho. The aircraft were flown until 1923.

With a maximum speed of 120kph and an endurance of 4 hours, it was a capable

maritime reconnaisance aircraft of its time.

The Grigorovich M-5 (alternative designation Shch M-5,

sometimes also Shchetinin M-5) was a successful Russian World War I-era two-bay

unequal-span biplane flying boat with a single step hull, designed by

Grigorovich. It was the first mass production flying boat built in Russia. The

aircraft designer Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich completed his first flying boat

(the model M-1) in late 1913, and produced a series of prototypes, gradually

improving the design, until the M-5 appeared in the spring of 1915, which was

to be his first aircraft to enter series production, with at least 100 being

produced, primarily to replace foreign built aircraft, including Curtiss Model

K and FBA flying boats.

The M-5 was of a wooden construction, the hull was covered

in plywood and the wings and tailplane were covered in fabric. Aft of the step

the hull tapered sharply into little more than a boom, supporting a

characteristic single fin and rudder tail unit, which was braced by means of

struts and wires. It was normally powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine

mounted as a pusher between the wings, but some used 110 hp Le Rhône or 130 hp

Clerget engines. The pilot and the observer were accommodated side-by-side in a

large cockpit forward of the wings, the observer provided with a single 7.62 mm

Vickers machine gun on a pivoted mounting.

Most of the M-5s served in the Black Sea or in the Baltic,

initially with the Imperial Russian naval air arm and later with both sides in

the Russian Civil War. Some remained in service until the late 1920s as

trainers, reconnaissance and utility aircraft. One M-5 fell into Finnish hands

when it was found drifting at Kuokkala in 1918. The aircraft was flown by the

Finnish Air Force until 1919, when it sank.

Soon after the declaration of independence, the Finnish

Civil War erupted and the Russians generally sided with the Reds – the

communist rebels. The Whites managed to seize a few aircraft from the Russians

but had to heavily rely on foreign pilots and aircraft. Sweden refused to send

men and material but individual Swedish citizens came to help the Whites. The

editor of the Swedish daily magazine Aftonbladet, Waldemar Langlet, bought an

N.A.B Albatross aircraft from the Nordiska Aviatik A.B. factory with funds

gathered by the Finlands Vänner (“Friends of Finland”) organization. This was

the first aircraft to arrive from Sweden. It was flown via Haparanda on 25

February 1918 by the Swedish pilots John-Allan Hygerth (who became the first

commander of the Finnish Air Force on 10 March 1918) and Per Svanbäck. The

aircraft made a stop at Kokkola and had to make a forced landing in Jakobstad

when the engine broke down. This aircraft was later given the designation F.2

in the Finnish Air Force (“F” came from the Swedish word “Flygmaskin”

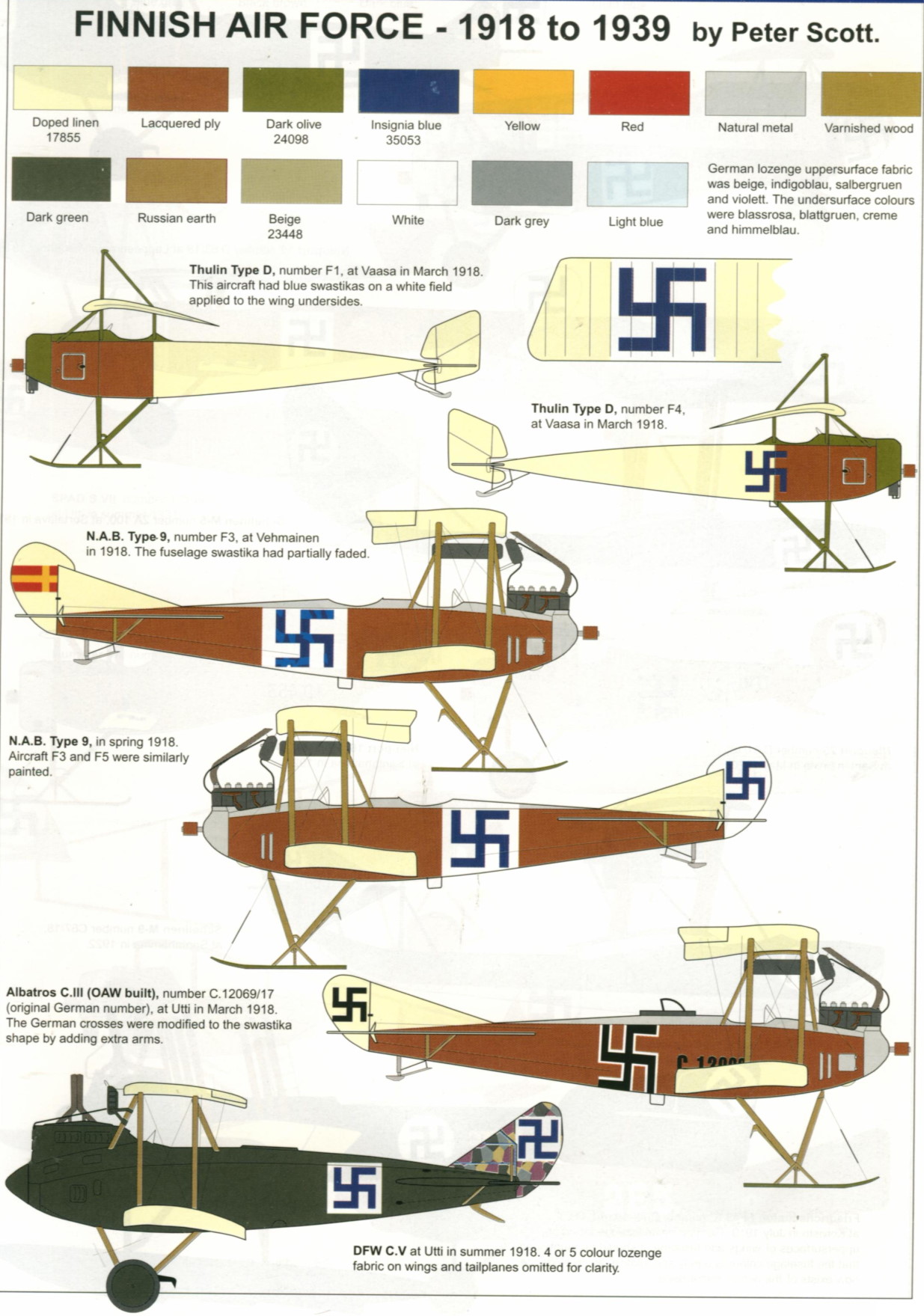

(aircraft)). The Swedish Count Eric von Rosen gave the Finnish White government

its second aircraft, a Thulin Type D.

Thulin Type D– this aircraft was a Swedish-built

Morane-Saulnier L

Thulin Type D– this aircraft was a Swedish-built

Morane-Saulnier L, a French parasol wing one or two-seat aeroplane of the First

World War. The Type L became one of the first successful fighter aircraft when

it was fitted with a single machine gun that fired through the arc of the

propeller, which was protected by armoured deflector wedges. Its immediate

effectiveness in this role launched an arms race in fighter development, and

the Type L was swiftly rendered obsolete. The original Type L used wing warping

for lateral control, but a later version designated Type LA was fitted with

ailerons. Built by Morane-Saulnier, large numbers of the Type L were ordered by

the French Aviation Militaire at the outbreak of the war, being designated the

MS.3. In total about 600 Type Ls were built and, in addition to the French air

force, they served with the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service and the

Imperial Russian Air Service. The aircraft had a maximum speed of 78 mph and an

endurance of 4 hours.

Count Carl Gustaf Ericsson von Rosen

The pilot of the first FAF plane was a Swedish noble and air

force enthusiast, Count Carl Gustaf Ericsson von Rosen, son of a famous

explorer. Eric von Rosen had been using a swastika as a personal owner’s mark.

He originally saw the symbol on runestones in Gotland, while at school. Knowing

that the symbol signified good luck for the Vikings, he utilized the symbol and

had it carved onto all his luggage when going on an expedition to South America

in 1901. Being a friend of Finland, he gave the newly-independent state an

aircraft, which signified the beginning of the Finnish Air Force. The aircraft,

a license manufactured Morane-Saulnier MS Parasol/Thulin D, was marked with his

badge, a blue swastika, and this blue swastika was adopted as the official

symbol of the Suomen Ilmavoimat decades before anyone had even heard of the

Nazi Hakenkreuz. The white circular background was created when the Finns tried

to paint over the advertisement from the Thulin Air Academy. The swastika was

officially adopted after an order by Mannerheim on 18 March 1918.

Von Rosen, incidentally, was also to become the

brother-in-law of Hermann Göring, when his wife’s sister, Carin von Kantzow,

married Göring. Göring was flying Eric von Rosen in bad weather from Stockholm

to Rockelstad Castle, at Lake Båven in Sörmland, Sweden. Due to bad weather

conditions, Göring had to stay at the castle. There he became acquainted with

the sister of von Rosen’s wife, Carin von Kantzow. She was at that time married

to a Swedish officer, but would go on to become Göring’s future wife.

Lt Nils Kindberg in the cockpit of the first Finnish Air Force aircraft – a Morane Parasol/Thulin Type D, at Umeå in Sweden on the morning of the 6th of March 1918.

The pilot, Lieutenant Nils Kindberg, flew the aircraft to

Vaasa on 6 March 1918, with von Rosen as a passenger. As this aircraft was

donated against the will of the Swedish government, and no flight permit had

been given, it resulted in a 100 kronor fine for Kindberg for leaving the

country without permission.

This aircraft is considered by some to be the first aircraft

of the Finnish Air Force, since the Finnish Air Force didn’t exist during the

Civil War, and since it was only the Red side who flew a few aircraft with the

help of some Russian pilots. The von Rosen aircraft was given the designation F.1.

The F.1 aircraft was destroyed in an accident, killing its crew, not long after

it had been handed over to the Finns.

Air activity of the Reds in the Finnish Civil War

Most of the airbases that the Russians had left in Finland

had been taken over by the Whites after the Russian pilots had returned to

Russia. The Reds were in possession of a few airbases and a few Russian

aircraft, mainly amphibious, with 12 aircraft in all. The Reds did not have any

pilots themselves, so they hired some of the Russian pilots that had stayed

behind. Among the machines acquired by the Reds were three Nieuport 10’s, one

Nieuport 17, one Nieuport 21, three Nieuport 23 fighters, one of the SPAD S.

VII and one Rumpler 6B –fighter. On the 24th of February 1918 five aircraft

arrived in Viipuri, and were quickly transferred to Riihimäki. The Reds created

air units in Helsinki, Tampere, Kouvola, and Viipuri. There were no overall

headquarters, the individual units served under the commander of the nearest

front line. A flight school was created in Helsinki, but no students were

trained there before the fall of Helsinki.

Two of the aircraft, one reconnaissance aircraft (a Nieuport

10) and one fighter aircraft (a Nieuport 17) that had arrived at Riihimäki were

sent to Tampere, and three to Kouvola. Four Russian pilots and six mechanics

also arrived to Tampere. The first war sortie was flown on March 1, 1918 over

Naitenlahtiwith a Nieuport aircraft from Tampere. The 1st recorded bombing took

place on 10 March in Vilppula. It seems likely that the Reds also operated two

aircraft over the Eastern front. The Reds mainly performed reconnaissance,

bombing sorties, spreading of propaganda leaflets, and artillery spotting. The

Reds’ air activity wasn’t particularly successful. Their air operations

suffered from bad leadership, worn-out aircraft, and un-motivated Russian

pilots. Some of the aircraft were captured by the Whites, while the rest were

destroyed.

Air Activity of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War

In January 1918 the Whites did not have a single aircraft,

nor pilots, so they had asked the Swedes for help. Sweden was a neutral nation

and would not send any official help. Sweden also forbade its pilots to go to

Finland. However, one Morane-Saulnier Parasol, and three NAB Albatross arrived

from Sweden by the end of February 1918. Two of the Albatross aircraft were

gifts from individuals supporting the White Finnish cause, while the third was

bought. It was initially meant that the aircraft would be used to support the

combat operations of the Whites, but the aircraft proved unsuitable. The Whites

also did not have any pilots, so all the pilots and mechanics came from Sweden.

One of the Finnish Jägers, Lieutenant Bertil Månsson, had been given pilot

training in Germany, but he stayed behind in Germany trying to secure aircraft

deals for Finland. 2 Flying Detachments were formed, one in Vilppula (Kolho)

from 28 Feb and one in Antrea from 25 March. From Kolho, Flying Detachment I

was transferred to Orivesi on 21 March, to Vehmainen on 28 March and finally to

Tampere on 10 Apr. The Aviation Detachment of the Karjala Corps was established

on 16 April 1918.

During the Civil War the White Finnish Air Force consisted of:

29 Swedes (16 pilots, two lookouts and 11 mechanics). Of the

pilots, only 4 had been given military training, and one of them was operating

as a lookout.

2 Danes (one pilot, one lookout)

7 Russians (six pilots, one lookout)

28 Finns (four pilots of whom two were military trained, six

lookouts, two engineers and 16 mechanics).

The first Air Force Base of independent Finland was founded

on the shore near Kolho. The base could operate three aircraft. The first

aircraft was brought by rail on March 7, 1918, and on March 17, 1918 the first

aircraft took off from the base. In 1918 the Finns took over nine Russian

Stetinin M-9 aircraft that had been left behind. White air activity consisted

mainly of reconnaissance sorties.

The first operative recon mission was flown in the morning

of 18 March over Lyly with an NAB type 9 Albatros aircraft. Two more recon

missions were flown in the afternoon of the same day. As the front line moved

south, towards Tampere, the AFB was moved first to Orivesi and then to Kaukajärvi

near Tampere. On the 11th and 12th flights on 31 March, 8 incendiary bombs were

hand-dropped on Tampere and on 2 Apr 3 explosive bombs were dropped. All in

all, the contribution of the White air force during the war was insignificant.

From March 10, 1918 the Finnish Air Force was led by the Swedish Lt. John Allan

Hygerth. He was however replaced on April 18, 1918, due to his unsuitability

for the position and numerous accidents.

Captain Mikkola with his pilots on the ice of

Vakkolahti in front of the Nieuport 23 fighter in March 1919. Pitkäsilta is

visible between the wings and in the middle is the Sortavala church. To the

left of the church is the Sortavala school.

The German Expeditionary Force brought several of their own

aircraft when they intervened in the Finnish Civil War, including one Rumpler

6-B Flying Boat, but these aircraft did not contribute much to the overall

outcome of the war. The German aircraft flew recon missions over Ahvenanmaa

starting from 2 March 1918 and over South-Finland starting from 3rd March.

Three bombs were dropped on the Kouvola Railway Station on 27 April 1918 and

the Germans established small air stations in Finland, 2 at Helsinki, 1 each at

Loviisa, Koivisto and Suursaari.

The First Years of the Ilmavoimat

The German intervention in the Finnish Civil War had the

result of binding Finland to Germany both politically and economically. A

German Officer, Hauptmann(Captain) Carl Seber, was put in command of the

Finnish Aviation Force from April 28, 1918 until December 13, 1918.

Hauptman Carl Seber

Seber was an experienced aviator, having been awarded the

Knight’s Cross of Saxony’s St. Henry Order on 4 July 1915 whilst serving in

Feldflieger-Abteilung 23. His citation reads: “Leader of the Royal Saxon

Feldflieger-Abteilung 23 since December 1914, Hauptmann Seber performed

heroically as an observer on many occasions. He carried out an especially

gallant act on November 18, 1914 when, with Oberleutnant [Gottfried] Glaeser,

they forced a superior French plane down with shots from a pistol on their

return from Amiens.” Seber had not actually commanded Feldflieger-Abteilung 23

“since December 1914,” but took command on 10 January 1915. Seber was also a

recipient of the Prussian Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Classes as well as the German

Army Observer Badge. Seber was largely responsible for the development of the

Air Force as an independent arm of the Finnish military and he stressed the

importance of the maritime aircraft.

Hauptman Seber (standing behind the Mascot)

By the end of the Civil War, the Finnish Air Force had 40

aircraft (these were already a mixture of 14 aircraft types, mostly seaplanes),

of which 20 had been captured from the Reds (the Reds did not operate this many

aircraft, but some had been found abandoned by the Russians on the Åland

Islands). Five of the aircraft had been flown by the Allies from Russia, four

had been gifts from Sweden and eight had been bought from Germany.

Santahamina, Koivisto, Sortavala and Lappeenranta

(transferred to Utti in June 1918). 5 Flying Detachments and a Flying Battalion

were established in October 1918. Finnish pilots and mechanics were sent to

Germany for training. The revolution in Germany and the end of the War put an

end to aircraft acquisitions from Germany and also to co-operation and training

with the Germans.

The “basic aircraft” of Sortavala Air Station was the

Friedrichshafen 49C, n C.72-18. Under the pontoons there are rollers for ground

transport. Maintenance Sergeant O. Koivunen beside the aircraft. Information:

produced in Germany, wooden, two-seat, wingspan 16,7 m; length 11,6 m; empty

weight 1485 kg; Max speed 140 km/h; Bentz Bz IV 6-cylinder engine 220 hp; used

at Sortavala 26.6.1918 – 22.3.1919.

The birth of the FAF during the Civil War had more symbolic

value than real strategic significance. Since the commanders of the future

Finnish Army had no practical knowledge of the usage of combat aircraft, the

new organization, named Suomen Ilmavoimat (Finnish Air Force) became an

independent branch of the armed forces. After the Civil War this originally

temporary solution became the new norm, and thus the FAF became one of the

oldest “independent” air forces in the world. This position gave the early

commanders of FAF considerable freedom to test new tactics and methods, and

during the 1920s 1930s the air force was as a result able to avoid stagnation

and conservative resistance to change. The FAF was free to test and operate

without hindrances. Yet the combination of the fast paced development of

aircraft designs and the limited military spending of the young republic

created a situation where innovative tactical solutions were often the only

thing that enabled the otherwise obsolete equipment of the Ilmavoimat to remain

usable in any potential conflict.

The first steps were the establishment of air units and

training programs, and at this point the presence and influence of foreign air

units based on Finnish soil was immense. The first military aircraft used in

the country were based from the naval aviation bases built by the Imperial Russian

Army or Navy during WWI, later on followed by German air units that were in

turn quickly replaced by a British naval aviation unit that operated on the

Gulf of Finland during the chaotic postwar years. At this point the Ilmavoimat

was trying to gain more aircraft from any and all available sources on a

limited budget, and all available planes were bought from the Entente powers

and from rebellious German garrison troops based in the Baltic states – these

were added to the air fleet left behind by the withdrawing Russian Army. Due

this “grab what you can”-policy the Ilmavoimat operated 20 different aircraft

types in the early 1920s and still had an extremely limited number of aircraft

in service. This type variety was to prove a fairly permanent problem in later

times, especially for the FAF technicians.

In the summer 1918, after the War of Independence was over,

the Ilmavoimat was organized into five air stations, three of which also acted

as training centers. Because of the enormous number of lakes in the country,

sea planes were regarded as the most suitable type of aircraft, thus four out

of the five air stations were in effect sea plane harbours. All of the stations

were located in southern Finland, as their main mission was surveillance and in

this way the network served well to cover the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga

areas.

The Establishment of the Sortavala Air Station

Capt. Väinö Mikkola established the Sortavala Air

Station and was the first commander. First Finnish military pilot’s wings no

1/17.9.1918. Mikkola died on the 7th of September 1920 together with Lieutenant

Leijer and Ensign Durchman when their Italian flying boats crashed in the Alps

during a transfer flight to Finland. This date is now the annual Finnish Air

Force memorial day.

The responsibility for establishment of I Field Air Station

at Sortavala was given to Lieutenant Väinö Mikkola. The detachment came to

Sortavala on the 23rd of June 1918. The mission of the air station was to

patrol the Lake Ladoga (Laatokka) sea front. Aerial reconnaissance was

important to the Finnish Army supreme command. Lieutenant Väinö Mikkola

established the Sortavala Air Station and was the first commander. He was

undisputedly the most experienced pilot in Finland. He had received his pilot

training during 1915 – 1916 in Russia, St. Petersburg and Baku. During World

War I Mikkola served as the commander on the aircraft hangar ship Orliza on the

Gulf of Finland and after that as the commander of the Hermanni Air Station.

Mikkola joined government service in January 1918 and in May he was registered

in the Finnish Army.

Mikkola was promoted to captain in July and given the first

Finnish military pilot’s wings number 1 on the 17th of September 1918. He

served as the commander of the Sortavala Air Station till the 4th of December

1919 when he was ordered to take command of the Aviation Battalion at

Santahamina. On the 16th of May 1920 he was promoted to Major. The location for

the air station was on the western shore of the Vakkolahti bay that divided the

town of Sortavala into two parts. Later Vakkolahti turned out to be too small

for air operations and in 1924 the unit moved south to Kasinhäntä.

The original four pilots: From left: Ensign Rafael

Hallamaa, Captain Väinö Mikkola (commander), Captain Leonard Lindberg (Kotsalo)

and Sergeant Eero Heinricius.

Pilot training in the Sortavala air station was started in

1919. Because of many technical problems with the aircraft there weren’t many

to be used. The situation eased a bit when Capt. Mikkola flew the Stetin M-16

flying boat “Winter-Farman” to Sortavala in July. This aircraft type was the

most important in the early 1920s until the I.V.L. A22 Hansas arrived in 1923.

In February 1920 I Aviation Detachment at Sortavala had four aircraft, two

Georges-Levys (3.B.401 and 3.B.402), one Farman (2.b.101) and a Rumpler C.VIII

(2.B.350). In the end of July another Farman arrived from Turku. From the

Russian war booty Farmans two more were assembled in 1921 which enabled a high

level of training activity till 1923.

In summer 1923 Aviation Detachment 3 had one flyable Caudron

(1.E.15), one Rumpler in repair (2.B.350) and one Farman stored.Because of the

strategic location of the Sortavala Air Station it had a very important mission

in the surveillance of the eastern border till the Tartu Peace Treaty. Because

of skirmishes along the border during 1921 – 1922, two Brequet reconnaissance

planes fitted with skis were transferred to Sortavala. The planes returned to

their base in March 1922.

Ensigns Alexander Tschernichin and Rainer Ahonius in

their flight suits on the pontoon of the Stetin M-16 sea plane. Both served

later as the commander of the air station: the first at Vakkolahti and the

latter at Kasinhäntä

The situation at Sortavala in the early 1920’s, that of

limited aircraft and a shoestring budget, was also typical of the other Air

Stations in this period. The Ilmavoimat had 31 aircraft of 14 different types

in 1919. By 1920 the air force aircraft situation was still poor. During 1918 and

1919 the air force had acquired 54 aircraft and now they were mostly destroyed

or in poor condition without leaving a mark in the development of the Finnish

Air Force.

In October 1920 the air force had 26 aircraft of seven

different types. Of those aircraft the six Georges-Levy flying boats could be

operated only during the open water summer-season. In a crisis the air force

could operate nine aircraft during wintertime and 15 during summertime. At the

beginning of 1921 the air force was practically without sea planes. This

situation would slowly change over the early 1920’s.

1919-1922: The immediate Post-War Years and French

Influence

After the defeat of Germany, the German officers left the

country and the Finnish Air Force lost its first actual commander. Also,

Finnish Pilots who were being trained in Germany were forced to return. The

next commanding officer of the Ilmavoimat was Lieutenant Colonel Torsten

Aminoff (December 14, 1918 to January 9, 1919). He was CiC for too short a

period to achieve anything, but under his replacement, Lieutenant Colonel

Sixtus Hjelm (January 10, 1919 to October 25, 1920), the Ilmavoimat received

it’s first budget and the Air Force Chief of Staff, Captain Bertel Mårtenson,

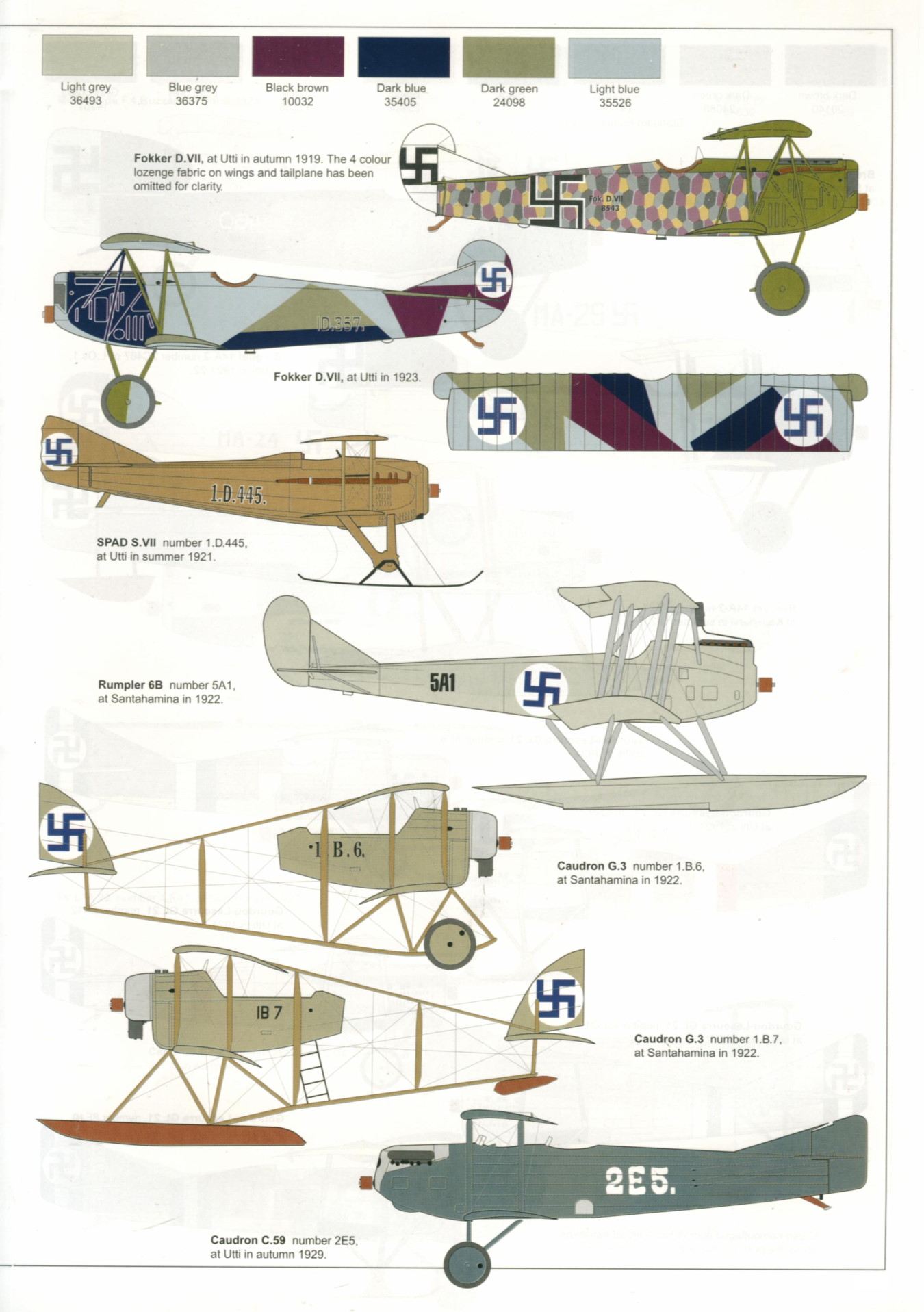

bought three Fokker D. VII fighters together with six Junkers J.1 low-level

ground attack, observation and Army cooperation aircraft.

The Junkers J.I

The Junkers J.I (manufacturer’s designation J 4; not to be

confused with the earlier, pioneering J 1 all-metal monoplane of 1915/16) was a

German “J-class” armored sesquiplane, developed for the low-level ground attack

role in close cooperation with friendly ground troops. It is especially

noteworthy as being the first all-metal aircraft to enter mass production. It

was a slow aircraft, but its metal construction and heavy armour was an

effective shield against battlefield’s small arms fire. In an extremely

advanced design, single-unit steel “bathtub” that ran from just behind the

propeller to the rear crew position, acted not only as an armour, but also both

as the main fuselage structure and engine mounting setup in one unit. The

armour was 5 millimetres (0.20 in) thick and weighed 470 kilograms (1,000 lb).

It protected the crew, the engine, the fuel tanks and the radio equipment.

The aircraft could be disassembled into its main components

– wings, fuesalage, undercarrage and tail – to make it easier to transport by

rail or road. A ground crew of six to eight could re–assemble the aircraft and

have it ready for flight within four to six hours. The wings were covered with

skin of aluminum that was .19 millimetres (0.0075 in) thick. This could be

easily dented so great care had to be taken when handling the aircraft on the

ground. The J.I was well-liked by its crews, although its ponderous performance

earned it the nickname “furniture van”. The aircraft first entered front

service in August 1917. They were used on the Western Front during the German

Spring Offensive (Kaiserschlacht “Kaiser’s Battle”) of March 1918. The

production at Junkers works was quite slow due to poor organization. There were

only 227 J.Is manufactured until the production ceased in January 1919 (some of

the production continued after the end of the war). None were apparently lost

in combat, a tribute to its tough armoured design, but a few were lost in

landing accidents, and other mishaps.

The aircraft was usually armed with two fixed, synchronized

machine guns firing between the propeller blades and with a single flexible gun

for use by the observer. Two downward-firing guns were sometimes installed for

the observer, but the difficulty of aiming these guns from a low, fast-flying

aircraft rendered them ineffective, and they were quickly removed. A radio link

connecting the aircraft with friendly ground troops in the forward area was

also generally provided. The J-I had a maximum speed of 96 miles per hour,

could climb to 6560 feet in 30 minutes, and had an endurance of 2 hours, a very

creditable performance for an aircraft of relatively low power. The good

performance of the aircraft was due in large part to the low value of the

zero-lift drag coefficient of 0.0335 and the high value of the maximum

lift-drag ratio of 10.3. The J-I was among the most aerodynamically efficient

of the World War I aircraft anf very effective in it’s ground-attack role. The

Ilmavoimat acquired six Junkers J.I’s in early 1919, the aircraft would remain

in service until 1932 and continued experience with the use of these aircraft

led to the formulation of the Ilmavoimat’s early ground-attack and

close-support doctrine. This in turn would later lead to the establishment of

the highly effective ground-attack squadrons of the Ilmavoimat which would go

on to fight through the course of the Winter War so effectively, following a

tactical doctrine which the British and Americans only came to adopt years

later.

Following the departure of the Germans, Finland sought

aviation expertise from the West. France was among the first countries to

establish diplomatic relations with Finland and the planning of the Finnish

Aviation Force strategy, aircraft types and training was given to a delegation

of French aviation “experts”. While command of the Ilmavoimat was retained in

Finnish hands, Finnish pilots and mechanics were sent to France for training.

Under French pressure, the Finnish HQ cancelled a deal (signed after the German

capitulation) to buy Fokker D.VII-fighters and Albratros recon aircraft from

Germany while the French aviation experts in Finland, led by Major Raoul

Etienne, the commander of Aviation Section of French Military Delegation in

Finland (the “Commission Francaise Militaire de Finlande, Aviation” stressed

the importance of the land-based aircraft and, unsurprisingly, in April 1919

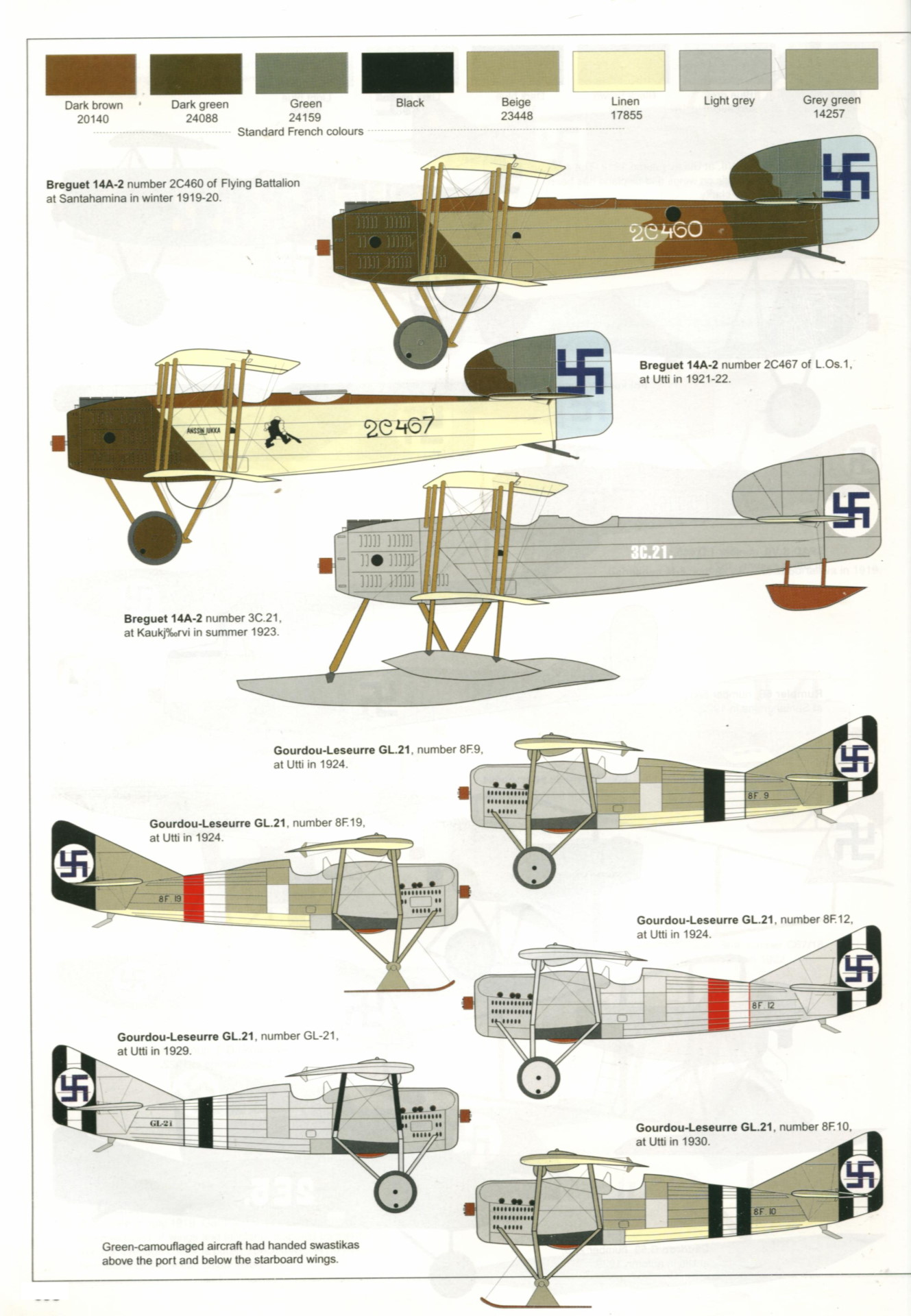

recommended the purchase of 30 Breguet 14 aircraft from France, allowing twenty

to always be ready for service and ten in repair at any time.

There was a strong opinion in favour of sea planes in the

Finnish Aviation Forces, partly due to the cost of building airfields and

consequently, the Ilmavoimat compromised and purchased 20 Great War-vintage

Breguet fighters and 12 Georges Levy flying boats whilst at the same time

beginning the long process of creating the necessary infrastructure and

training systems to maintain and improve the Ilmavoimat. Of the twenty Breguet

14 A2 aircraft ordered in 1919 (the order also included over two hundred (221)

used Fiat A-12bis engines from French surplus stock for the aircraft), the

first four arrived to Finland in July 1919. In 1921 ten more aircraft arrived,

followed by eight in 1922. The planes delivered in 1921 were without engines.

The type remained in Finnish service until 1927. One aircraft (3C30) remains

today in the Central Finland Aviation Museum, where it is undergoing

restoration.

The Bregeut 14 A2 could carry four 10 or 12.5 kg bombs, a

camera and a wireless transmitter. It had dual controls for the observer with

armament consisting of one synchronised fixed Vickers machine gun for the pilot

and twin TO3 ring mounted Lewis machine guns for the observer. Machine guns and

the ring mounting were not always installed in Finnish aircraft, sometimes the

observer had only a single mg. Michelin bomb racks were located under the lower

wing, just outboard of the inner interplane struts. The aircraft formed the

backbone of the Ilmavoimat for several years.

The first aircraft were assigned to the 2nd Aviation

Detachment (Ilmailuosasto 2, Ilm.Os) at Utti, which was in 1921 renamed to 1st

Aviation Detachment (Ilmailuosasto 1) and in 1924 to Land Reconnaissance

Squadron (Maatiedustelulaivue, Ma.T.L) and finally in 1926 to Land Flying

Squadron (Maalentoeskaaderi, M.L.E). In summer they were often operated from

Perkjärvi, which was the only full size airfield, besides Utti, in Finland.

After 1920 also the Aircraft Factory at Santahamina had a small airfield.

During winters the Breguets were operated all over the country on skis.

The Breguets were the first true combat aircraft of the

Ilmavoimat

At Utti French mechanics assembld the first aircraft and

French instructors taught Finnish pilots to fly the Breguets. Instructors

included Lieutenants Bourdon and Moutonnieux and Sous-Lieutenant Discours. Some

aircraft were probably assembled at Santahamina. The first Finnish pilot to

perform aerobatics in Finland was Captain Gunnar Holmqvist. He made a vertical

turn and side slip with a Breguet (2C461) on 4 September 1919. Four Breguet 14

aircraft were moved from Utti to Perkjärvi on Karelian Isthmus on 30 August

1919. From there reconnaissance flights were made to the St. Petersburg area,

where the forces of General Judenitsh were observed. On 25 October 1919 Captain

Holmqvist and his observer Captain H. Lilja photographed Russian Red and White

Army positions and bombed the Komandantsky (called Kolomäki by Finns) airfield.

Their aircraft took one hit from Russian anti-aircraft fire. Reconnaissance

flights on the south east border were also made in 1920 and 1922.

In the summer of 1920 Telefunken radios were used for the

first time in artillery spotting rehearsals at Perkjärvi, these were continued

on a yearly basis from 1920 through to 1923. Using the Breguets, the Ilmavoimat

also started to fly a mail service between Helsinki and Tallinn from 12

February 1920. The hard winter had isolated Estonia from the rest of the world,

but also made flights over the Gulf of Finland somewhat safer. The ongoing

peace negotiations with Soviet Russia had increased the need for diplomatic

contacts and ten return flights were made through to March 10th, when the sea

was again open, by 2nd Lts Armas Anthoni, Carl-Erik Leijer and Tauno Hannelius

(later Hannus) and the French Sergeant Major (Maréchal des Logis) Pierre

Burello, carrying diplomatic mail and occasionally a VIP. On March 3rd one of

the planes carrying a diplomat made a landing on Wrangler Island (Prangli?) 25

km north east of Tallinn, due to fuel shortage. The service was not continued

in 1921, but in February 1922 mail flights were made from Santahamina in

Helsinki to Lasnamäki airfield in Tallinn. The book “Finland I Krig 1939-1945”

has a photo on page 29 showing the Finnish Foreign Minister in full flying

outfit standing in front of a Breguet 14. The text says “Foreign Minister

Holsti returning from Warsaw in 1922”. It seems unlikely that he really flew

from Warsaw, but was rather being transported from Tallinn to Helsinki.

The Ilmavoimat sent 1 M-16 to help the Estonians in the

Estonian War of Liberation in January-February 1919. While voluntary Finnish

expeditionary forces took part in the so-called Olonets Campaign (part of the

Heimosodat) in Eastern Karelia in April-June 1919, the Ilmavoimat did not

participate. However, in June-August 1919 the Ilmavoimat reconnoitered Soviet

territory and sea and bombed Soviet ships and submarines that entered Finnish

territorial waters. The Ilmavoimat also attacked Kronstadt harbour as a

retaliation to Soviet bombings of Finnish territory. The Tartu Peace Treaty

with the Soviet Union was concluded on 14 October, 1920, the last guerilla

fighters retreated to Finland as late as February 1922 and the borders between

the two countries were finally established on 1 June 1922. In the summer of

1920, Finland raised its defensive preparedness in Ahvenanmaa (the Asland

Ilands) as the province wanted to join Sweden and the Swedes were interested in

taking possession. The League of Nations resolved the situation in 1921 before

the dispute lead to any military actions being taken.

In 1921, in conjunction with the purchase of the Breguet 14

A2 aircraft, the Ilmavoimat had also purchased 12 Georges Levy G.L. 40 HB2

Flying Boats from France for maritime reconnaissance and patrolling. The

Georges Levy G.L. 40 HB2 was a three-seated amphibious biplane aircraft

designed in 1917 with a maximum speed of 90mph, a cruising speed of 71mph, a

range of 248 miles and was armed with 1 machinegun and up to 400lbs of bombs.

The aircraft was designed by Blanchard and Le Pen and the aircraft was also

known as the Levy-Le Pen. It was claimed to be the best French amphibious

aircraft of World War I, but that is probably due to the limited production of

such aircraft in France at that time. The Ilmavoimat was not happy with this

purchase – three aircraft were lost in accidents that claimed lives – and it

was nicknamed “the flying coffin” in the 1920s.

A New Commanding Officer for the Ilmavoimat

In October 1920 the Ilmavoimat received a new commander when

a young (29) former cavalry officer, Jager Major Arne Somersalo was tasked to

reform and expand the FAF. The young commander realized that he had only nine

combat-capable Breguets at his disposal, and that the new air force had to

acquire all kinds of technical equipment to enable the training of new pilots.

All military airfields available for use at this time were constructed for the

needs of Imperial Russia, and thus located at places of secondary importance

for the new strategic situation. There were thus many challenges to be

overcome. Commander-in-Chief of the Suomen Ilmavoimat from 1920 to his death in

action in 1944, Somersalo had a strong influence on the future of FAF. He

strongly opposed the early conceot of a general workhorse plane type,

forcefully advocating the creation of separate bomber, air reconnaissance and

fighter units. Somersalo argued that in the future fighter units would be the

most important element of FAF, a force that he envisioned to develop into a

“combat-worthy service that controls the national airspace in all military

fronts.” He also fiercely defended the independent position of FAF while

maintaining otherwise supportive attitude towards cooperation with Army and

Navy.

Somersalo met with much opposition over the course of his

career, even considering resignation in 1926 after the General Staff decided to

continue further down the path recommended British General Walter Kirke.

However, Somersalo made the decision to continue to “fight from within” and his

persistence paid off in the early to mid-1930’s, as we will see.

Arne Sakari Somersalo

Arne Sakari Somersalo (born 18 March 1891 in Tampere as Arne

Sommer – died 17 August 1944 near Riga, Latvia) was a Finnish officer and

anti-communist activist. Somersalo was educated at the University of Helsinki

before studying natural sciences at the University of Jena. He fought in the

German army after having completed a German officer’s course at Lockstedt

starting in 1915. His family had a German background. After that he received an

officer’s commission and fought first as hussar leutenant in the Hussar

regiment n:o 16 in 1916–1917. In 1917–1918 he was in the German 9th Army Corps

as a staff officer. He would later claim that the war had been the death of old

Europe and argued that one of its main positives was that it had “rescued our

nation from the deadly, slimy embrace of a loathsome cuttlefish” in reference

to Russia. He transferred straight to the Finnish Army and from 1920 to 1944

was the commander of the Finnish Air Force. He became peripherally involved in

politics in 1926 when he started contributing to the right wing journal

Valkoinen Vartio and then was instrumental in founding the fiercely

anti-communist Finnish Defence League. He joined the Lapua Movement in 1930 and

then the Patriotic People’s Movement (IKL) in 1932, when he considered

resigning from the Ilmavoimat and standing for election to Parliament.

However, with his promotion to Kenraalimajuri in 1932 and

substantial increases in the Ilmavoimat’s budget looming, he made the decision

to withdraw completely from politics and focus his career on the continued

strengthening of the Ilmavoimat. It was primarily Somersalo’s continued

advocacy of the creation of separate air reconnaissance, bomber, ground-attack

/ dive-bomber and fighter units and the building up of fighter units as the

most important element of the Ilmavoimat that was instrumental in the decisive

role played by the Ilmavoimat in the Winter War. Promoted to Kenraaliluutnantti

on 3 Oct 1941, Somersalo continued to command the Finnish Air Force through the

Peace between the Winter War and Finland’s entry into WW2. He was killed in

action near Riga, Latvia on 17 August 1944 as he was visiting the 1st Polish

Armoured Division (the Black Devils, then fighting under command of the Suomen

Maavoimat) in the advance southwards through Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and

into Poland in 1944.

(ATL Note: This differs from the OTL. In reality, Somersalo

resigned as commander-in-chief of the Ilmavoimat in 1926, disheartened by the

Military High Command’s decision in 1926 to plan future expansion on the Kirke

Memorandum. For Somersalo, the continuing uphill struggle was too much, and he

resigned. His successor was Col. Vaino Vuori, an infantry officer with no

experience in military aviation who took no risks and decided to follow the

guidance of “foreign experts”. In reality, Somersalo’s legacy faded fast.

Somersalo went on to become involved in politics, editing the right wing

journal Valkoinen Vartio from 1926 and then founding the fiercely

anti-communist Finnish Defence League. He joined the Lapua Movement in 1930 and

then the Patriotic People’s Movement (IKL) in 1932, serving as the Member for

Turku in Parliament from 1933 to 1935. He was also the editor in chief of the

IKL party newspaper Ajan Suunta from 1931 to 1935. Recalled to active service

for the Winter War, he acted as Chief of Staff for the frontline at Suomussalmi

and was awarded the Order of the Cross of Liberty for his actions. During the

Winter War, Somersalo acted as liaison officer for the German SS Division Nord

on Finnish Lapland. He was killed in action near Kiestinki (Kestenga), USSR on

17 August 1941).

As a part of this ongoing development, Finland made a choice

typical of the era, and sought to create a national aviation industry to

provide the Ilmavoimat with new trainers and later on licence-build and

domestic-made combat aircraft as well. The idea was first proposed in 1920

(Somersalo firmly believed in the benefits of the plan and organised a strong

political lobby to support it), and a year later the first repair workshop of

the Ilmavoimat was expanded into the Airforce Airplane Factory (Ilmavoimien

Lentokonetehdas, IVL) and immediately begun to manufacture the Caudron G.3

trainer aircraft built under licence, which was followed very shortly by the

building under licence of the A22 Hansa (a license-built copy of the German

designed Hansa-Brandenburg W.33).

With the creation of IVL the Ilmavoimat and Finnish industry

had established the basis of an effective and reliable maintenance system for

Finnish combat aircraft. Initially the factory was administered by the War

Ministry, with the repair workshop and factory acting as separate departments under

the Ilmavoimat. For practical reasons they were combined together in 1928, and

the State Aircraft Factory (Valtion Lentokonetehdas, VL) was born.

Caudron G.3 Primary Trainer -1920-1924

The Ilmavoimat purchased twelve Caudron G.3 aircraft from France in 1920 for use as primary trainers. Six of these were built in Finland by the newly established Santahaminan Ilmailutelakka between 1921 – 1923. Two aircraft and spares were purchased from Flyg Aktiebolaget on April 26, 1923 together with a Caudron G.4 for 100,000 Finnish markka. The aircraft was easy to fly and repair and thus very suitable as a trainer. The Finnish-constructed aircraft had worse flying characteristics than the French machines due to a bad wing profile. The FAF used a total of 19 Caudron G.3 aircraft, which was called Tutankhamon in Finland. The Caudron G.3 was used by the FAF between 1920 and 1924.

The Caudron G.3 was a single-engined French biplane built by

Caudron, widely used in World War I as a reconnaissance aircraft and trainer.

It first flew in May 1914 at their Le Crotoy aerodrome. The aircraft had a

short crew nacelle, with a single engine in the nose of the nacelle, and twin

open tailbooms. It was of sesquiplane layout, and used wing warping for lateral

control, although this was replaced by conventional ailerons fitted on the

upper wing in late production aircraft. Following the outbreak of the First

World War, it was ordered in large quantities. Usually, the G.3 was not

equipped with any weapons, although sometimes light, small calibre machine guns

and some hand-released small bombs were fitted to it. It continued in use as a

trainer after ceasing combat operations until after the end of the war. One

aircraft (1E.18) is currently being repaired at the Hallinportti Aviation

Museum.

IVL A.22 Hansa – ordered 1922, retired 1936, reactivated

1939, retired 1940

Hansa-Brandenburg. Technical information: Wooden, two-seat sea plane. Weight 2124 kg, Max speed 170 km/h, wingspan 15,85 m, length 11,10 m, endurance 6 hours. Weapons: navigator’s twin machine gun, bombs 4×10 kg

The IVL A.22 Hansa was a Finnish-licensed copy of the German

Hansa-Brandenburg W.33, a two-seat, singe-engined low-winged monoplane flying

boat. The Hansa-Brandenburg W.33 was designed in 1916 by Ernst Heinkel and

entered German service in 1918. Twenty-six aircraft of this design were built,

only six of them before the collapse of Germany. The W.33 proved to be an

excellent aircraft, with the Hansa-Brandenburg monoplanes considerably

influencing German seaplane design. Several copies appeared in 1918, such as

the Friedrichshafen FF.63, the Dornier Cs-I, the Junkers J.11, and the L.F.G.

Roland ME 8. After the war a version of the W.29 was used by Denmark, while

Finland purchased a number of W.33 and W.34 aircraft from Germany.

In 1921 Finland purchased a manufacturing license for the

W.33. The first Finnish-built Hansa made its maiden flight on November 4, 1922

and in Finland was designated the IVL A.22 Hansa. This aircraft was the first

industrially manufactured aircraft in Finland, and during the following four

years between 1922 and 1925 a total of 120 of this aircraft-type were

manufactured for the nacent Ilmavoimat. The IVL A.22 Hansa would become the

second most numerous aircraft built in Finland for the Finnish Air Force and

would continue to be used in maritime service until 1936. The A.22 Hansa had a

crew of 2 and was a single-engined floatplane with a maximum speed of 99mph.

Hansa startup for engine test. During startup the propeller

was turned only “once behind the compression”. This lessened the fear of

getting hit by the propeller during startup. There was often a fire in the

carburetor during startup. The fire was usually suppressed by the mechanic

putting his hat over the intake. Notice the squadron eagle insignia on the

fuselage.

The A.22’s were finally retired from service and mothballed

in 1936 as the Ilmavoimat’s aircraft modernisation program picked up speed. As

the threat of war came closer in the late 1930’s, approximately 80 of these

aircraft were brought back into service and were initially used for Maritime

Patrol activities over the Gulf of Bothnia, largely being flown by student

pilots. They were used in the same role over the summer of 1940 before being finally

retired on the signing of the Sept. 1940 Peace Treaty with the USSR.

The Gourdou Leseurre-GL-22 Fighter (ordered 1923)

After his appointment and on realising that Finland lacked

any practical fighter aircraft force, Somersalo in 1921 drafted the Air Force

Development Plan, which planned for a fighter strength of 136 aircraft. It was

decided to fill this need by acquiring the first squadron from abroad and then

build up to the total strength by construction of the remaining aircraft in

Finland.

In October 1922, the Ilmavoimat Headquarters sent a tender

to the Dutch Fokker, the French Gourdou & Leseurrelle and the British

Aircraft Disposal Company requesting one fighter for comparison purposes. Bids

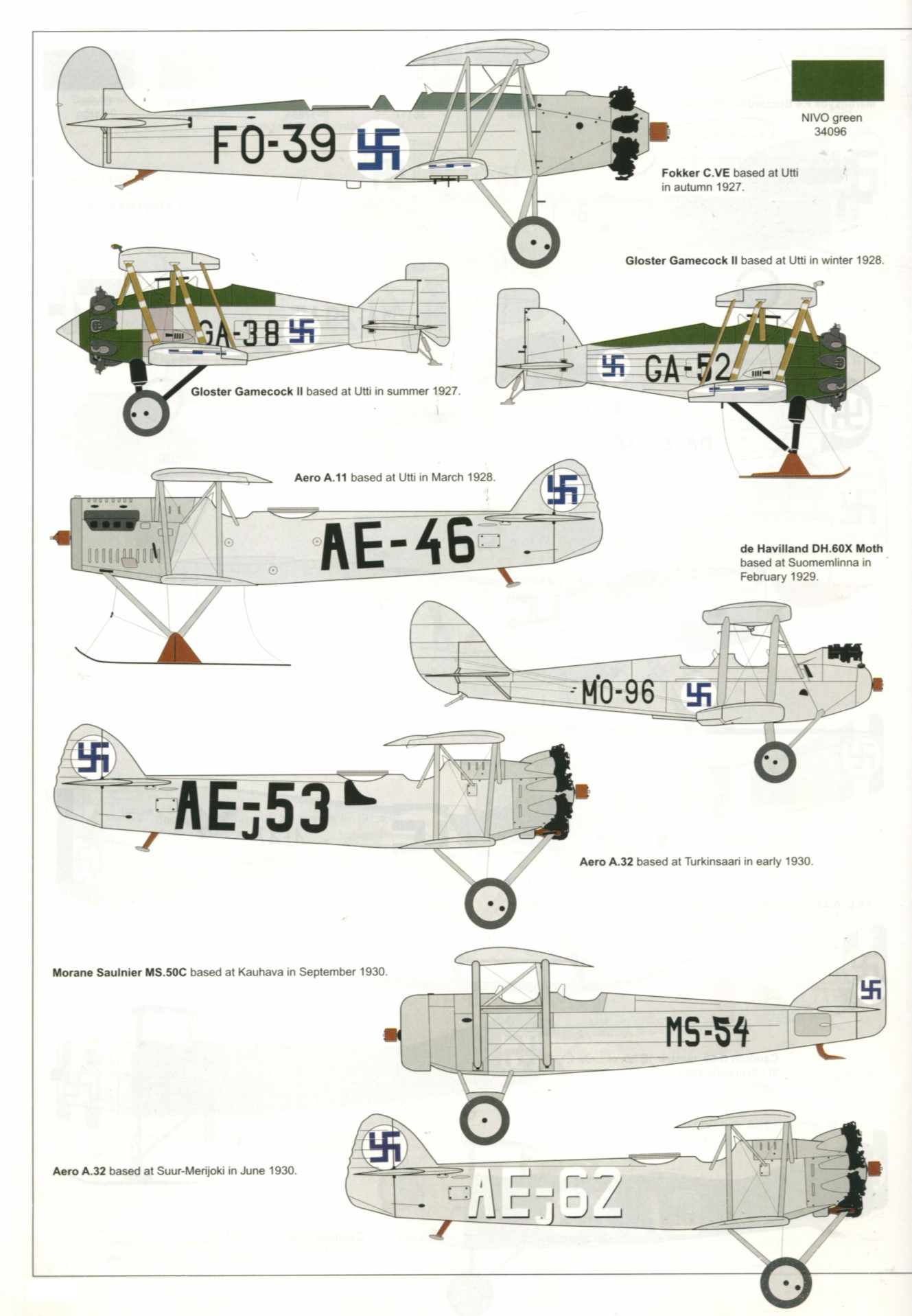

were received and the aircraft were ordered in January 1923. A Fokker DX,

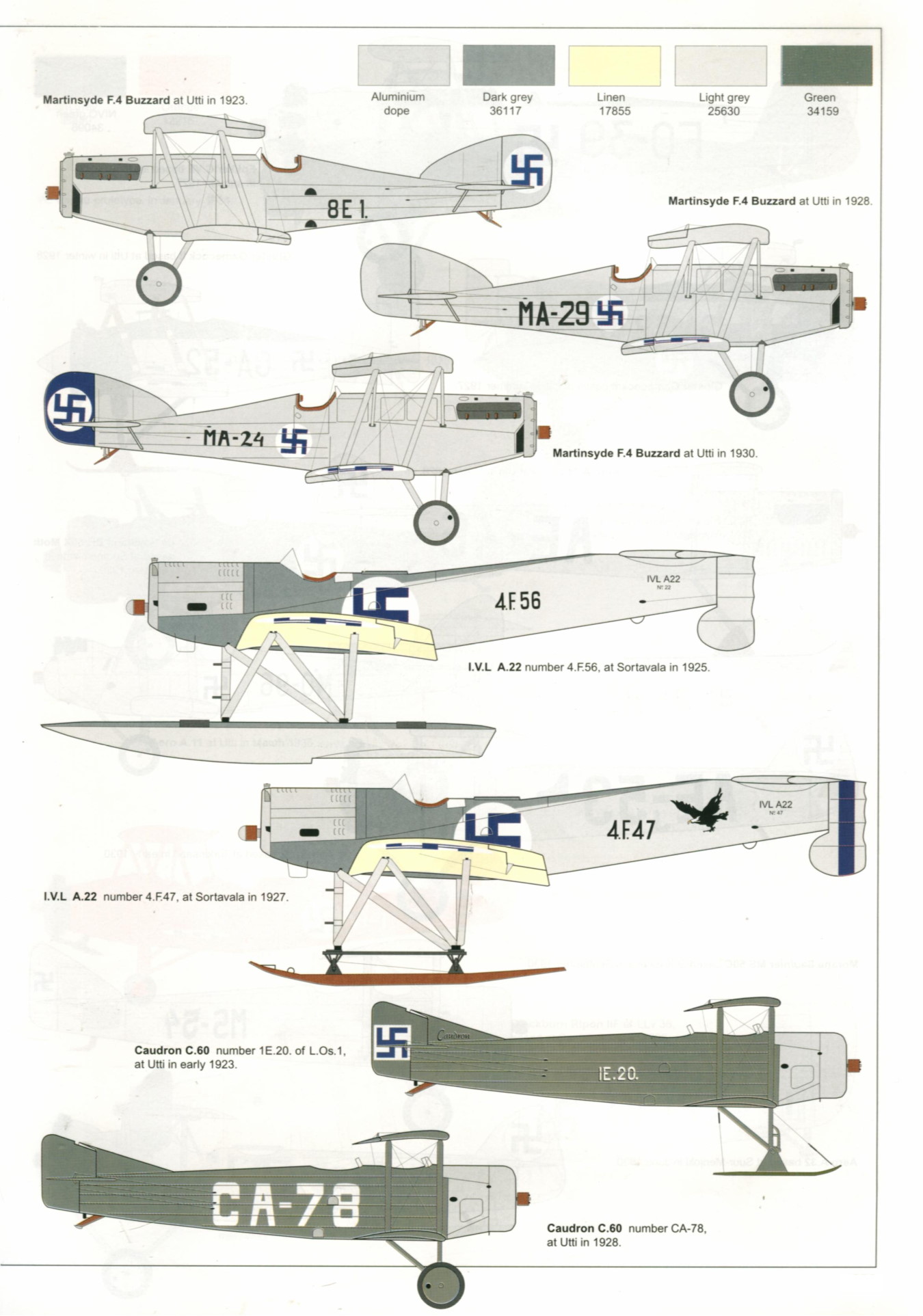

Gourdou Leseurre-GL-21 and a Martinsyde F.4 Buzzard arrived in the country

rapidly. After evaluation, the Gourdou-Leseurre was selected and 18 GL-22

machines were purchased (allowing some for spares) and the aircraft arrived in

Finland in the summer of 1924.

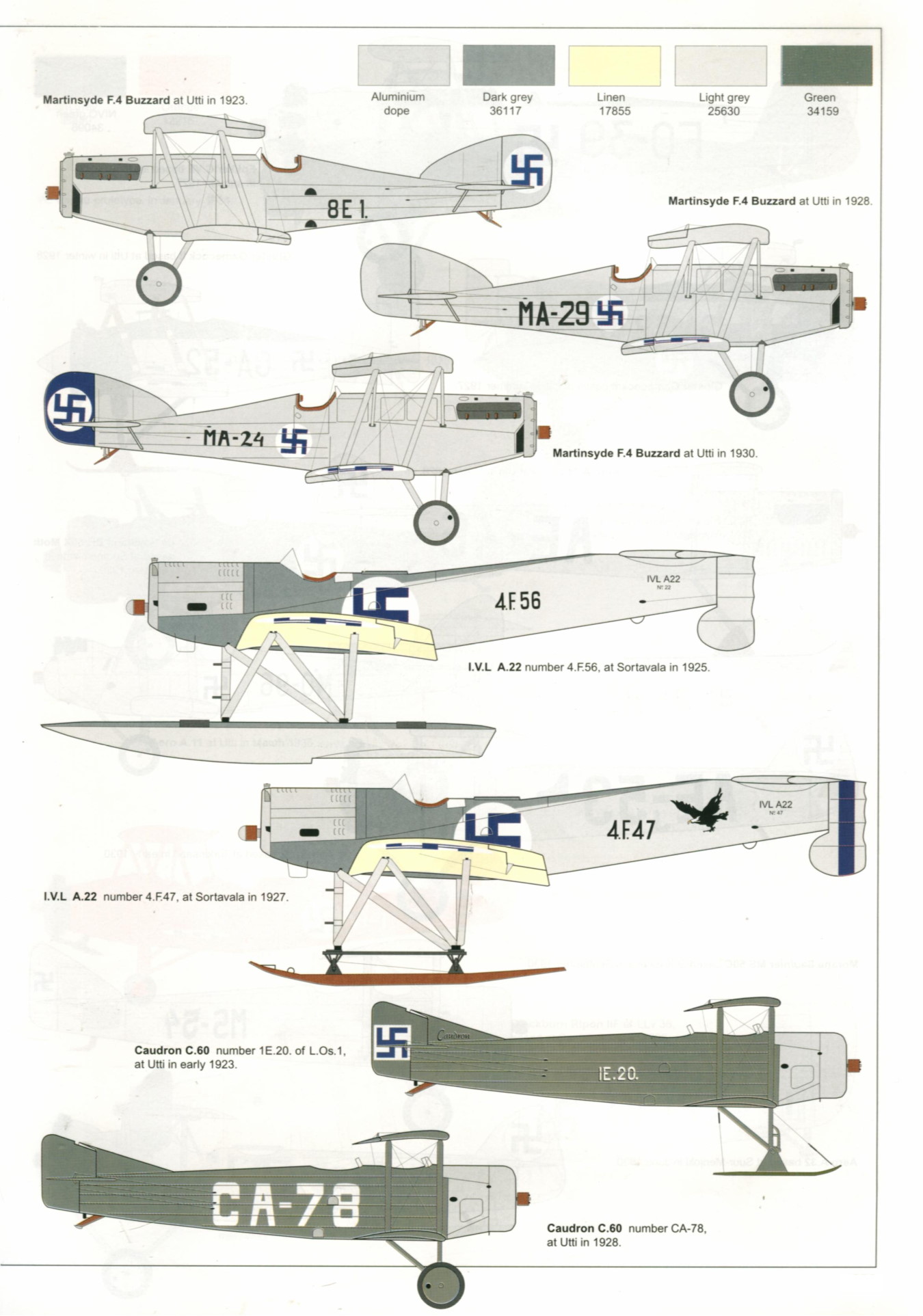

Caudron C.60 Primary Trainer – ordered 1923, retired 1936

The Ilmavoimat purchased 30 Caudron C.60s from France in

1923. A further 34 aircraft were licence built in Finland between 1927-1928.

The Finnish Air Force had a total of 64 Caudron C.60s in service, where they

were used as primary trainers until 1936, when they were retired as more modern

trainers were brought into service. With a maximum speed of 93mph, a ceiling of

13,120 feet and an endurance of 5 hours, they were a typical biplane trainer of

the 1920’s.

A Lack of Vision and Goals

Overall, it has to be said that the Suomen Ilmavoimat flight

operations through the 1920’s suffered from inexperience combined with a lack

of a clear vision and goals. Flying was an end in itself, there was little real

understanding of how to use air power in a real war and the Ilmavoimat would

not have been capable of accomplishing the wartime missions assigned to the

service. While flight hours climbed steadily, most of the flights were training

flights and there wasn’t a lot of tactical training because many of the pilots

were inexperienced and needed advanced flying training and sea plane conversion

training. There were also a number of fatal accidents over this period –

between 1923 and 1930 there were 20 fatal accidents with 42 persons lost. The

end result of this was that the Hansa also received somewhat of a reputation as

a “flying coffin” although it should also be kept in mind that the Ilmavoimat

flew more with the Hansas than with all other types combined.

Foreign Advisors – directing the Ilmavoimat into a

dead-end for a time….

With the basic requirements for future development programs

more or less in place, Finland now once again sought foreign military expertise

and guidance from the victors of the Great War. This time a military advisor

team arrived from Britain, led by General Walter Kirke. The British advisors

created a development program that was planned as a temporary basis for the

future Ilmavoimat. The program conflicted with the views of Somersalo in many

cases. British officers disregarded the importance of fighters and instead

promoted the offensive capabilities of air arm, envisioning the bombing of

enemy territories as the main future mission of Finnish Air Force. The Kirke Memorandum

was strongly influenced by the ideas of the Italian theorist Giulio Douhet, but

its general outlines were strictly conservative. The memo emphasized the

importance of flying boats and naval aviation for Finnish coastal defense and

recommended future investments in naval bomber aircraft.

The British General Kirke created his memorandum as an outline for the short-term development of the Ilmavoimat. Despite this fact his work directed the development of the Ilmavoimat into a dead end for a considerable period of time after its central ideas had been proved obsolete and unpractical.

While the Suomen Ilmavoimat had carried out advanced air

combat and bomber training for it’s pilots and navigators starting from the

mid-1920’s, little attention had been paid to initially to joint exercises with

the Army and Navy, largely due to the reluctance of the Ilmavoimat to

participate in such exercises. The British Specialist Committee had stressed in

their study the importance of joint exercises in developing the Air Force and

while these became routine in the late 1920’s, they were only adequate at most.

There were shortcomings in the planning and execution of the exercises, with a

major problem being that the exercise leadership was unaware of the Ilmavoimat

operating capabilities. Another common problem were ongoing communications

problems between the Ilmavoimat Pilots and the Army units they were operating

with.

These were all issues that would be addressed successfully through the 1930’s as Somersalo and his senior officers gained in experience and studied the subject of the air war – experience and studies that would result in the setting of a clear strategic and tactical vision and goals for the Ilmavoimat.