Origins

The professionalization of the Roman army after Marius’

reforms led directly to the use and abuse of consular power by individual

generals seeking to usurp the power of the Senate. Consequently the last five

decades of the Republic were characterized by two important features: the

jostling for power and status by a number of dynamic political players, and the

calamitous civil wars generated by their personal, be it selfish or altruistic,

ambitions. It was the last of these republican warlords who was to emerge

victorious as the first Roman emperor under the new name of Augustus.

Officially he was addressed as princeps, that is the first citizen of the

state, and his reign was the beginning of the Principate.

The army of the Principate established by Augustus drew

heavily on the nomenclature and traditions of the dead Republic. But it was

new. He decided to meet all the military needs of the empire from a standing,

professional army, so that there was no general need to raise any levies

through conscription (dilectus), which in actual fact he did on only two

occasions, namely following the military crises in Pannonia (AD 6) and Germania

(AD 9). Military service was now a lifetime’s occupation and career, and pay

and service conditions were established that took account of the categories of

soldier in the army: the praetorians (cohortes praetoriae), the citizen

soldiers of the legions (legiones), and the non-citizens of the auxiliaries

(auxilia). Enlistment was not for the duration of a particular conflict, but

for twenty-five years (sixteen for the praetorians), and men were sometimes

retained even longer. At the end of service there was a fixed reward, on the

implementation of which the soldier could rely. The loyalty of the new army was

to the emperor, as commander-in-chief, and neither to the Senate nor the Roman

people.

Cassius Dio, writing of the events of 29 BC, reports two

speeches made before Augustus by his counsellors, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and

Caius Maecenas, in which the best way of securing the continuation of the Roman

state and defence of its empire was discussed. Agrippa apparently advocated the

retention of the traditional system (by which men would be conscripted to serve

short periods, and then released into civilian life). Maecenas, on the other

hand, argued for ‘a standing army (stratiôtas athanatous in Cassius Dio’s

Greek) to be recruited from the citizen body [i.e. legiones], the allies [i.e.

auxilia] and the subject nations’, and despite Agrippa’s contention that such

an army could form a threat to the security of the empire, carried the day.

Dialogues were a convention of ancient historiography, and

these speeches need not be judged the true record of a real debate between the

two. In part at least they reflect the political situation of Cassius Dio’s own

time and were aimed at a contemporary emperor, perhaps that psychopathic

fratricide and builder of the eponymous baths in Rome, Caracalla (r. AD

211–217). Nevertheless, in 13 BC, after he had returned from Gaul, Augustus

ordained that terms of service in the legions should in future be fixed at

sixteen years, to be followed by a four or five-year period ‘under the flag’, sub

vexillo, to be rewarded by a fixed cash gratuity, though this could be commuted

to a plot of land, measuring 200 iugera (c. 50 ha), in a veteran-colony in the

provinces.

However, the scheme did not work, for in AD 5 discontent was

rife and in the following year major army reforms were carried out by the

emperor. The fundamental problem was that veterans were discontent with sub

vexillo, which apparently entitled them to lighter duties after their

sixteen-year stint. But no government, ancient or modern, is noted for keeping

its promises. So some alterations were made to the conditions of service. The

number of years that the new recruit had to serve under arms was raised to

twenty years, with a further period (not specified, but probably at least five

years) in reserve. The cash gratuity was now fixed at 12,000 sestertii (3,000

denarii) for an ordinary ranker, a lump sum the equivalent of more than

thirteen years’ pay.

Seemingly as part of this same package, but recorded by

Cassius Dio under the following year (AD 6), Augustus masterminded the creation

of a military treasury (aerarium militare). Its function was to arrange the

payment of bounties to soldiers. Augustus opened the account with a large gift

of money from his own funds, some 170 million sestertii according to his own

testimony, but in the longer term the treasury’s revenues were to come from two

new taxes imposed from this time onwards on Roman citizens: a 5 per cent tax on

inheritances and a 1 per cent tax on auction sales in Rome. The introduction of

these taxes caused uproar, but taxation was preferable to displacement,

acrimony and ruin, which had been the consequences of land settlement

programmes of the civil war years. Augustus thus shifted a part of the cost of

the empire’s defence from his own purse to the citizenry at large. But the

wages of serving soldiers (225 denarii per annum for an ordinary ranker)

continued to be paid by the imperial purse; Augustus could brook no

interference, or divided loyalties there. The management of the army,

particularly its pay and benefits, were from the start one of what Tacitus

calls ‘the secrets of ruling’. Power was protected and preserved by two things,

soldiers and money. And so the security and survival of the emperor and his

empire was now the sole responsibility of the emperor and his soldiers.

The legions had been the source of Augustus’ power. However,

serious mutinies broke out in Pannonia and Germania in AD 14 partly because the

legionaries were worried about their conditions of service after the death of

Augustus, so closely had he become associated with their emoluments. But there

was obviously significant discontent with low rates of pay, especially in contrast

to the praetorians, long service, and unsuitable land allocations. Here Tacitus

takes up the story:

Finally Percennius had acquired a team of helpers ready for mutiny. Then he made something like a public speech. ‘Why’, he asked, ‘obey, like slaves, a few commanders of centuries, fewer still of cohorts? You will never be brave enough to demand better conditions if you are not prepared to petition – or even threaten – an emperor who is new and still faltering.

Percennius, a common soldier, was the ringleader of the

mutineers in Pannonia, then garrisoned by three legions (VIII Augusta, VIIII

Hispana, XV Apollinaris) based in a camp near Emona (Ljubljana). Once the

mutiny was crushed, he was to be hunted down and executed for his troubles.

These mutinies clearly showed the danger of having too many

legions (there were four involved in the Germania mutiny) in the same camp.

Also, living in tents, even during the summer months, on the Rhine and Danube

frontiers must have been miserable to say the least. The bleakness of life

under canvas is the subject of a telling passage of Tertullian: ‘No soldier

comes with frolics to battle nor does he go to the front from his bedroom but

from tents that are light and small, where there is every kind of hardship,

inconvenience, and discomfort.’

As mentioned above, in the time of Augustus the annual rate

of pay for a legionary was 900 sestertii (225 denarii), Percennius’ piddling

‘ten asses a day’. But Percennius’ complaint was all in vain, the basic rate

remaining so until Domitianus, who increased the pay by one-third, that is, to

1,200 sestertii (300 denarii) a year. Wages were paid in three annual

instalments, the first payment being made on the occasion of the annual new

year parade when the troops renewed their oath to the emperor. Official

deductions were made for food and fodder (for the mule belonging to the

mess-group, contubernium). In addition, each soldier had to pay for his own

clothing, equipment and weapons, but these items were purchased back by the

army from the soldier or his heir when he retired or died. These were the

official charges. As we know, Tacitus records that one of the complaints of the

mutineers was that they had to pay sweeteners to venal centurions in order to

gain exemption from fatigues. Another complaint was that time-expired soldiers

were being fobbed off with grants of land in lieu of the gratuity of 12,000

sestertii, and these plots tended to be either waterlogged or rock-strewn.

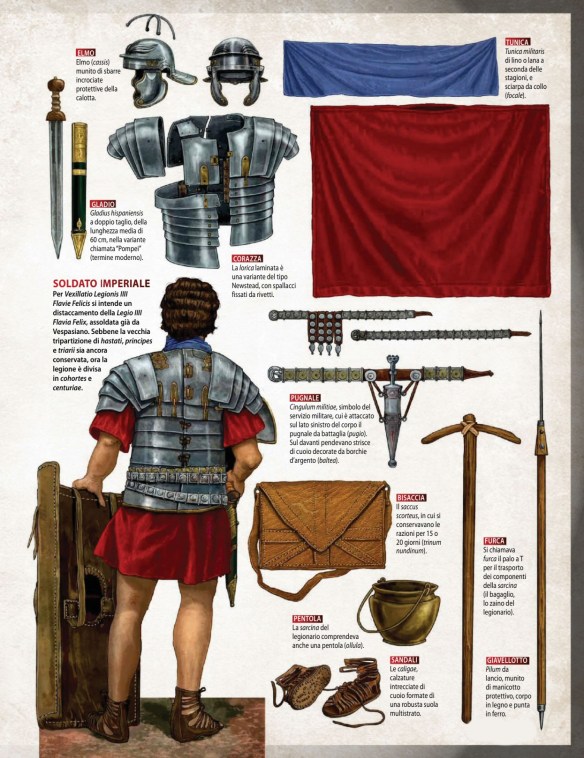

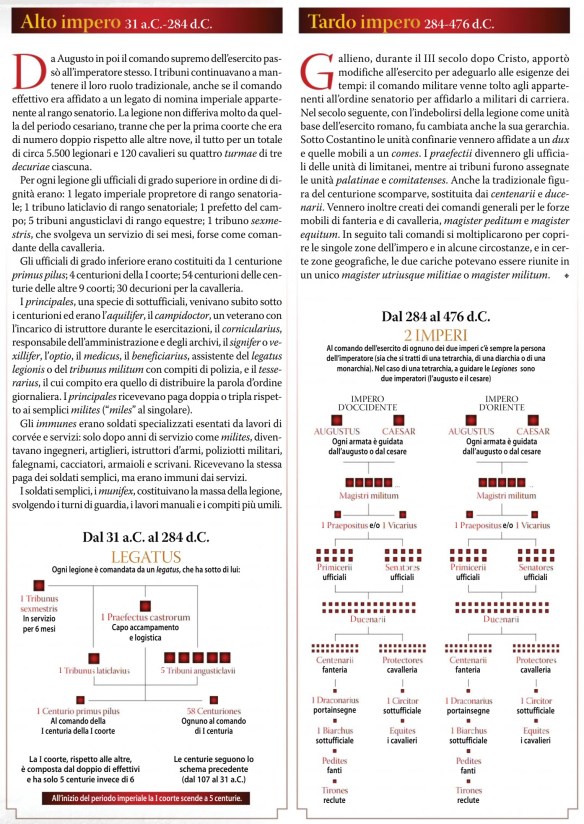

Organization

A great body of information on the unit size and

organization of the Principate army has been amassed by the patient work of

several generations of scholars. The literary sources are often obscure or

contradictory on the details of unit structures, but we are fortunate in that

much information has been derived from epigraphic, numismatic and papyrological

record as well as that of archaeology. Here contemporary evidence, if not

overabundant, is explicit and reliable. As a result a fairly coherent picture

of the army’s structure has emerged and what follows, then, is the briefest of

sketches of the army as it existed in Neronian times.

As an instrument of war the Principate army presented a

powerful picture, and there is certainly little about it that a modern infantry

soldier would fail to recognize. The professional standing force of a modern

size, conscription, military training, institutionalized discipline, weapons

factories, administrative and combat staffs, military maps, roads, logistics

systems, military hospitals, intelligence services, communications, strategy

and tactics, efficient killing technologies, siege machines, rank structures,

scheduled promotions, permanent records, personnel files, uniforms, regular

pay, and even military pension schemes – to name but a few – had already become

part of every day, military life.

Legion

Men had a thousand reasons for joining the army, but mainly

they were escaping from poor local conditions or looking for what they hoped

would provide a regular source of food and income. Unsurprisingly, therefore,

the army seems to have been most attractive as a definite career to the poorest

citizens. For such men, long underfed and ill-clothed, the legions offered a

roof over their head, food in their bellies, and a regular income in coin.

Basic military pay was not the road to riches, but there was always the chance

of bounties and donatives, and the certainty of a discharge bonus, a rich

contrast to civilian unemployment. Army pay certainly did not depend on the

weather, taxation, rent, interest payments or fluctuating prices. Overall, a

soldier’s life was more secure than that of an itinerant labourer (an unpaid

labourer would starve; an unpaid soldier still ate), and he enjoyed a superior

status too.

Of course, we must remember the harsher side of such a

career. The rewards of army life may have been greater, but so were the risks.

A soldier ran the risk of being killed or crippled by battle or disease, but

also on an everyday basis was subject to the army’s brutal discipline. And then

there was maltreatment, which did not include the routine harshness or the

standard Spartan quality of military life. The dividing line between discipline

and maltreatment was crossed when officers treated their men with unnecessary

severity, when they paid no attention to their welfare, and when they expected

fear rather than respect from their men. Such officers firmly believed that you

got more out of men by using brutality, than by treating them with patience

tempered by firmness. Most of us are familiar with the martinet centurion

Give-me-Another, nicknamed because of his habit of beating a soldier’s back

until his gnarled vitis – the twisted vine-stick that was his badge of rank –

snapped and then shouting for a second and a third.

Such a bully and a beast was common in the army, the general

assumption being that soldiers had to be treated roughly so as to toughen them

up for fighting, yet to many people in the empire who struggled to survive at

subsistence level, the well-fed soldier with his ordered existence in his

well-built and clean camp must have seemed comfortably off. Soldiers also

shared a comradeship with their fellow soldiers, which was often warm and

comforting. And so the legions became permanent units with their own numbers

and titles and many were to remain in existence for centuries to come.

Most prominent in the life of the empire was the army, the

organization of which began, and almost ended, with the legion. Yet from

Augustus onwards the emperor commanded no more than twenty-five legions in

total (twenty-eight before the Varian disaster of AD 9), which seems paltry

considering the extent of the empire. Legions were probably in the order of

5,000 men strong (all ranks) and composed of Roman citizens, though sickness

and death could quickly pare away at this figure. Legionaries were mostly volunteers,

drawn initially from Italy (especially the north), but increasingly from the

provinces. As the first century progressed, many recruits in the west were

coming from the Iberian provinces, Gallia Narbonensis, and Noricum, and in the

east from the Greek cities of Macedonia and Asia. Thus, by the end of the

century the number of Italians serving in the legions was small. Statistics

based on nomenclature and the origins of individuals show that of all the

legionaries serving in the period from Augustus to Caius Caligula, some 65 per

cent were Italians, while in the period from Claudius to Nero this figure was

48.7 per cent, dropping even further to 21.4 per cent in the period from

Vespasianus to Trajan. Thereafter, the contribution of Italians to the manpower

of the legions (but not of the Praetorian Guard naturally) was negligible. It

must be emphasized, however, that these statistics represent all legionaries in

the empire. In reality, there was a dichotomy in recruitment patterns between

the western and eastern provinces, with legions in the west drawing upon Gaul,

Iberia, and northern Italy, while those stationed in the east very quickly

harnessed the local resources of manpower.

Ordinarily a legion consisted of ten cohorts (cohortes),

with six centuries (centuriae) of eighty men in each cohort, apart from the

first cohort (cohors prima), which from AD 70 or thereabouts was double

strength, that is five centuries of 160 men. Commanded by a centurion

(centurio) and his second in command (optio),4 a standard-size century

(centuria) was divided into ten eight-man subunits (contubernia), each

contubernium, mess-group, sharing a tent on campaign and pair of rooms in a

barrack block, eating, sleeping and fighting together. Much like small units in

today’s regular armies, this state of affairs tended to foster a tight bond

between ‘messmates’. There would have been a strong esprit de corps among men

built upon the deep concern each had for everyone. In the pressure cooker

environment of small combat units where soldiers are forced into close contact

with one another, they worked together, they fought together, they shared

discomfort and death and victory. This was man-to-man friendship, a gutsy bond.

A spirit of military brotherhood would explain why many soldiers (milites)

preferred to serve their entire military career in the ranks despite the

opportunities for secondment to specialized tasks and for promotion.

Nonetheless, a soldier (miles) who performed a special function was excused

fatigues, which made him an immunis, although he did not receive any extra pay.

Finally, there was a small force of 120 horsemen (equites

legionis) recruited from among the legionaries themselves. These equites acted

as messengers, escorts and scouts, and were allocated to specific centuries

rather than belonging to a formation of their own. Thus, the inscription on a

tombstone from Chester-Deva describes an eques of legio II Adiutrix pia fidelis

as belonging to the centuria of Petronius Fidus. Citizen cavalry had probably

disappeared after Marius’ reforms, and certainly was not in evidence in

Caesar’s legions. However, apart from a distinct reference to 120 cavalry of

the legion in Josephus, the equites seem to have been revived as part of the

Augustan reforms.

Detachments

When territory was added to the empire, a garrison had to be

put together to serve in its defence. New legions were sometimes raised, but

normally these green units were not themselves intended for service in the new

province. So when an invasion and permanent occupation of Britannia became a

hard possibility under Caius Caligula, two new legions, XV Primigenia and XXII

Primigenia, were formed in advance. Their intended rôle was as replacements for

experienced legions earmarked to join the invasion force: XV Primigenia to

release legio XX from Neuss-Novaesium, and XXII Primigenia to release XIIII

Gemina from Mainz-Mogontiacum. The invasion force that eventually sailed for

southern Britannia in the summer of AD 43 consisted of XX and XIIII Gemina,

along with II Augusta, which had been at Strasbourg-Argentoratum, this camp was

now left vacant, and VIIII Hispana from Sisak-Siscia in Pannonia, which may

have accompanied the outgoing legate governor, Aulus Plautius, on his journey

to take up his new post as the expeditionary commander. It must be said,

however, that only II Augusta and XX are actually attested as taking part in

the invasion itself, though all four legions are recorded very early in

Britannia.

Nevertheless, transfers of legions to different parts of the

empire could leave long stretches of frontier virtually undefended, and

wholesale transfers became unpopular as legions acquired local links. An

extreme case must be that of II Augusta. Part of the invasion army of AD 43,

its legatus legionis at the time was in fact the future emperor Vespasianus,

this legion was to be stationed in the province for the whole time Britannia

was part of the empire. An inscription from near Alexandria, dated AD 194, is

of particular interest to us as it records the names of forty-six veterans of

legio II Traiana fortis who had just received their honourable discharge and

had begun their military service in AD 168. Of the forty-one whose origins are

mentioned, thirty-two came from Egypt itself and twenty-four of these state the

camp as their place of birth, or more precisely origo castris, ‘of the camp’.

It is likely that most of them were illegitimate sons born to soldiers from

local women living in the nearby canabae legonis, that is, the extramural

civilian settlement associated with the garrison. So it seems that many

recruits were the sons of serving soldiers or veterans, and in time these

soldiers’ sons became a fertile source of recruits, particularly so as

soldiers’ sons did not have to make a major adjustment from a civilian to a

military world. With bastard sons following their soldier fathers into the

army, the custom developed of sending not an entire legion to deal with

emergencies, but detachments drawn from the various legions of a province. As

we have seen, in the year AD 69 legionary detachments played a major rôle in

the formation of the Vitellian and Flavian armies.

Detachments from legions operating independently or with

other detachments were known as vexillationes, named from the square flag,

vexillum, which identified them. Until the creation of field armies in the late

empire, these vexillationes were the method of providing temporary

reinforcements to frontier armies for major campaigns. And so it was that

Cnaeus Domitius Corbulo received a vexillatio from legio X Fretensis, then

stationed at the Euphrates crossing at Zeugma, during his operations in

Armenia. Later he was to take three vexillationes of a thousand men (i.e. two

cohorts) from each of his three Syrian legions (III Gallica, VI Ferrata, X Fretensis)

to the succour of Caesennius Paetus, whose army was retreating posthaste out of

Armenia. Likewise, despite the disaster to legio VIIII Hispana during the

Boudican rebellion, no new legion was despatched to Britannia, but a vexillatio

of 2,000 legionaries gathered from the Rhine legions.

Auxiliaries

Under Augustus the rather heterogeneous collection of

auxiliary units, auxilia, serving Rome was completely reorganized and given

regular status within the new standing army. Trained to the same standards of

discipline as the legions, the men were long-service professionals like the

legionaries and served in units that were equally permanent. Recruited from a

wide range of warlike peoples who lived just within or on the periphery of

Roman control, with Gauls, Thracians and Germans in heavy preponderance, the

auxilia were freeborn non-citizens (peregrini) who, at least from the time of

Claudius, received full Roman citizenship on honourable discharge after

completion of their twenty-five years under arms.

Tacitus tells us that the Batavi, on the lower Rhine, paid

no taxes at all, but ‘reserved for battle, they are like weapons and armour,

only to be used in war’. The Batavi made capital stuff for a soldier, and from

Tacitus we hear of eight cohortes and one ala, nearly 5,000 warriors from the

tiny region of Batavia serving Rome at any one time. He also remarks of a

cohors Sugambrorum under Tiberius, as ‘savage as the enemy in its chanting and

clashing of arms’, although fighting far from its Germanic homeland in Thrace.

Further information concerning these tribal levies comes from Tacitus’ account

of the ruinous civil war. In April AD 69, when Vitellius marched triumphantly

into Rome as its new emperor, his army also included thirty-four cohortes ‘grouped

according to nationality and type of equipment’.

Take the members of cohors II Tungrorum for instance, who

had been originally raised from among the Tungri who inhabited the northeastern

fringes of the Arduenna Silva (Ardennes Forest) in Gallia Belgica. Under the

Iulio-Claudian emperors it was quite common for such units to be stationed in

or near the province where they were first raised. However, the events of the

AD 69, with the mutiny of a large proportion of the auxilia serving on the

Rhine, would lead to a change in this policy. After that date, though the Roman

high command did not abandon local recruiting, it did stop the practice of

keeping units with so continuous an ethnic identity close to their homelands.

As expected, by the late first century, units were being

kept up to strength by supplements from the province where they were now

serving or areas adjacent to it. Such units retained their ethnic identities

and names, even if they enlisted new recruits from where they were stationed. The

epitaph of Sextus Valerius Genialis tells us that he was a trooper in ala I

Thracum, and his three-part name indicated he was a Roman citizen. But it adds

that he was a ‘Frisian tribesman’. So, Genialis came from the lower Rhine,

served in a Thracian cavalry unit stationed in Britannia and styled himself a

Roman. So after the military anarchy of AD 69, auxiliary cohorts were plausibly

made up of a great diversity of individuals of all kinds of nationalities.

Nonetheless, despite such conflicting backgrounds and cultures, the Roman

military system forged these foreign cohorts into cohesive, aggressive fighting

units.

Auxiliary cohorts were either 480 strong (quingenaria, ‘five

hundred strong’) or, from around AD 70, 800 strong (milliaria, ‘one-thousand strong’).

Known as cohortes peditata, these infantry units had six centuries with eighty

soldiers to each if they were quingenaria, or if milliaria had ten centuries of

eighty soldiers each. As in the legions, a centurion and an optio commanded a

century, which was likewise divided in to ten contubernia.

Now to turn to matters concerning mounted auxilia. Cavalry

units known as alae (‘wings’, it originally denoted the Latin-Italian allies,

the socii, posted on the flanks of a consular army of the Republic) are thought

to have consisted of sixteen turmae, each with thirty troopers commanded by a

decurio and his second-in-command the duplicarius, if they were quingenaria

(512 total), or if milliaria twenty-four turmae (768 total). The later units

were rare; Britannia, to cite a single example, had only one in its garrison.

Drawn from peoples nurtured in the saddle – Gauls, Germans, Iberians and

Thracians were preferred – every horseman of the alae was well mounted, knew

how to ride, and was strong enough and skilful enough to make lethal use of his

long straight sword, the spatha. The alae provided a fighting arm in which the

Romans were not so adept.

Additionally there were mixed foot/horse units, the cohortes

equitatae. Their organization is less clear, but usually assumed, following

Hyginus, to have six centuries of eighty men and four turmae of thirty troopers

if cohors equitata quingenaria (608 total), or ten centuries of eighty men and

eight turmae of thirty troopers if cohors equitata milliaria (1,056 total). An

inscription, dated to the reign of Tiberius, mentions a praefectus cohortis

Ubiorum peditum et equitum, ‘prefect of a cohort of Ubii, foot and horse’,

which is probably the earliest example of this type of unit. It may be worth

noting here that this Tiberian unit was recruited from the Ubii, a Germanic

tribe distinguished for its loyalty to Rome. In Gaul Caesar had employed

Germanic horse warriors who could fight in conjunction with foot warriors,

operating in pairs.

Organized, disciplined and well trained, the pride of the

Roman cavalry were obviously the horsemen of the alae, but more numerous were

the horsemen of the cohortes equitatae. Having served for some time as

infantrymen before being upgraded and trained as cavalrymen, these troopers

were not as highly paid, or as well mounted as their brothers of the alae, but

they performed much of the day-today patrolling, policing and escort duties.

Specialists

In addition, as in earlier times, there were specialists

fulfilling roles in which Roman citizens, better utilized as legionaries, were

traditionally unskilled. The best-known of these specialists were archers from

Syria and slingers from the Baleares, weapon preferences that were solidly

rooted in cultural, social and economic differences.

Among the Romans the bow seems never to have been held in

much favour, though after the time of Marius it was introduced by Cretans

serving Rome. During our period, however, archers were being recruited from

amongst experienced people of the eastern provinces. Like slingers, it is

possible they were equipped as regular auxiliaries rather than their exotic

appearance on Trajan’s Column would indicate (e.g. scene lxx depicts them with

high cheekbones and aquiline noses, wearing voluminous flowing skirts that

swing round their ankles). Certainly first-century tombstones show archers in

the usual off-duty uniform of tunic with sword and dagger belts, cinguli,

crossed ‘cowboy’ fashion.

Also likely is the possibility that individual soldiers

within any given unit acquired the necessary ability to use bows, rather than

simply relying on specialist units. In his military treatise, among other

matters, Vegetius includes a recommendation that at least a quarter of all

recruits should be trained as bowmen. Yet, despite his sound advice here,

Vegetius says it is the self-bow that will be used in training soldiers in the

art of archery. It is assumed, therefore, that the standard of archery was

obviously not expected to be the same as that provided by specialists units

such as cohors I Hamiorum Sagittariorum, who were trained and experienced in

precisely the sort of warfare in which the Principate army was decidedly

deficient.

Equipment

The Roman army is seen as rather standardized in terms of

its equipment, especially its armour. This view, however, is rather misleading

and we would probably be closer to the truth envisaging a situation where, as

long as the soldier had fully functional equipment, then the army did not mind

what type it was. I am not suggesting that Roman soldiers went into action

looking like the crew of a pirate ship, but as long as their equipment did the

job it was required to do and was well maintained, the pattern was of secondary

importance. Besides, as with all professional, state-sponsored armies,

improvements in equipment took place relatively slowly, necessitating the

continued use of material that was of considerable age, even if certain older

items, helmets in particular, were relegated to inferior grades of soldier. It

may be said with truth of Roman arms that as long as a piece remained in

serviceable condition, it continued to be used – generally speaking, given a

minimum amount of daily care, weapons and equipment have a long-life span.

Thus, many soldiers would not have had top-of-the-line helmets and equipment.

All the same, without going into too much detail, the Principate army was made

up of a high proportion of armoured fighting men, men who were also as a rule

individually more heavily armed and armoured than their adversaries, than any

other.

It should be said at this juncture that the Romans were not

at all resistant to technological innovation on cultural grounds because the

innovation in question originated with a hated enemy; this was a luxury they

fully understood that could not be afforded. Indeed, the Romans were adept at

cultural borrowing, though they left their own unique stamp on each borrowed

idea (and institution) in moulding it to their own purposes.

Finally, when we write of such things, we should not

dissociate the weapon from the man who wields it, nor the load from the man who

carries it. The legionary, like all professional infantry soldiers before. Finally,

when we write of such things, we should not dissociate the weapon from the man

who wields it, nor the load from the man who carries it. The legionary, like

all professional infantry soldiers before his day and after, was grossly

overloaded – alarmingly so according to some accounts. In the evening of his

life, Cicero wrote of ‘the toil, the great toil, of the march: the load of more

than half a month’s provisions, the load of any and everything that might be

required, the load of the stake for entrenchment’. Normally, perhaps, a

legionary carried rations for three days, not the two weeks to which Cicero

refers (a brilliant orator, yes, a practical soldier, no). However, it has been

estimated that the legionary was burdened with equipment weighing as much as

thirty-five kilograms if not more. As Edward Gibbon justly says, this weight

‘would oppress the delicacy of a modern soldier’.

Helmet (galea)

Roman helmets, of Celtic inspiration, were made of iron or

copper alloy (both bronze and brass are known). Bronze was a more expensive

metal, but cheaper to work into a helmet: whereas iron helmets could only be

beaten into shape, bronze ones were often ‘spun’ on a revolving former (a

shaped piece of wood or stone) from annealed bronze sheets.

Whatever the material or type (viz. Coolus, Imperial Gallic,

Imperial Italic), however, the main features were the skull-shaped bowl, a

large neck guard to provide protection from blows to the neck and shoulders,

cheek pieces to protect the sides of the face – these were hinged so they could

move freely – and a brow-guard, which defended against downward blows to the

face. The helmet invariably left the face and ears exposed, since the soldier

needed to see and hear to understand and follow battlefield commands. Soldiers

often punched or scratched their names and those of their centurions onto their

helmets to prevent mistaken ownership or indeed theft.

Unlike infantry helmets, cavalry helmets had extensions of

their cheek pieces to cover the ears. Often shaped as simulated ears

themselves, the extra protection to the face was clearly considered to be more

important than some loss of hearing. Also the neck guard was very deep,

reaching down to close to the shoulders, but not wide, since this would have

made the rider likely to break his neck if he fell from his horse. The cavalry

helmet, therefore, protected equally well against blows to the side and the

back of the head, vital in a cavalry mêlée when the two sides soon become

intermingled.

Hobnailed boots (caligae)

The standard form of military footwear for all troop types,

caligae consisted of a fretwork upper, a thin insole and a thicker outer sole.

The twenty-millimetre thick outer sole was made up of several layers of cow or

ox leather glued together and studded with conical iron hobnails – evidence

from Kalkriese, the probable site of the Varian disaster in AD 9, suggests 120

per boot. Weighing a little under a kilogram, the one-piece upper was sewn up

at the heel and laced up the centre of the foot and onto the top of the ankle

with a leather thong, the open fretwork providing excellent ventilation that

would reduce the possibility of blisters. It also permitted the wearer to wade

through shallow water, because, unlike closed footwear that would become

waterlogged, they dried quickly on the march.

There is that well-known story from Josephus relating to the

tragic death of a centurion during the siege of Jerusalem in AD 70. Of

Bithynian origin, centurion Iulianus was bravely pursuing the enemy across the

inner court of the Temple when the hobnails of his caligae skidded on the

smooth marble paving and he crashed to the deck, only to be surrounded and

eventually despatched by those he had audaciously chased. This was a possible

danger of course, but in most circumstances the hobnails served to provide the

wearer with better traction. Not only that, they also served to reinforce the

caligae, and to allow the wearer to inflict harm by stomping. More to the

point, the actual nailing pattern on the sole was arranged ergonomically and

anticipated modern training-shoe soles designed to optimize the transferral of

weight between the different parts of the foot when placed on the ground.

Experiments with modern reconstructions have demonstrated that, if properly

fitted of course, the caliga is an excellent form of marching footwear, and can

last for hundreds of kilometres. Much like all soldier’s equipment past and

present, caligae would have needed daily care and attention, such as the

replacement of worn or lost hobnails or the cleaning and buffing of the

fretwork upper.

If there is one thing of importance to an infantryman, it is

his feet. Tacitus represents the Flavians during the civil war as demanding

clavarium, or ‘nail money’, that is, money to buy hobnails for their boots. At

the time of the claim the Flavian legionaries were making their long march to

Rome. Suetonius seems to be alluding to a similar claim when, referring to

marines (classiarii), who had regularly to march from Ostia or Puteoli to Rome,

they demanded of Vespasianus calciarium, or ‘boot-money’. The emperor, famed

for his sardonic wit (and measures), is said to have suggested to them they

make the journey barefoot, a practice that was still being continued in

Suetonius’ day. Soldiers were charged, amongst other things, for their rations,

clothing and boots by stoppages debited to their pay accounts and these demands

must have been for extra pay to offset the expense of boot repairs.

With such footwear fully laden Roman soldiers could ‘yomp’

for miles, provided of course that they adapted themselves to local conditions.

In cold weather, for instance, caligae could be stuffed with wool or fur, while

one piece of sculptural evidence depicting a parade of praetorians, namely the

Cancellaria Relief, suggests that thick woollen socks (undones), toeless and

open at the heel, could also be worn with the boot. We also have that

well-known writing tablet from Chesterholm-Vindolanda:

I have sent (?) you… pair of socks (undones). From

Sattua two pairs of sandals (soleae) and two pairs of underpants (subligares),

two pairs of sandals… Greet… ndes, Elips, Iu…, … enus, Tetricus and all

your messmates (contubernales) with whom I hope that you live in the greatest

of good fortune.

Written in colloquial Latin, this letter was evidently sent

to a soldier serving at Chesterholm-Vindolanda as the author refers to his

contubernium, one of which, Elpis, bears a Greek name (literally Hope). The

recipient was probably a member of one of three auxilia units known to have

been stationed here at the end of the first century, namely cohors III

Batavorum, cohors VIIII Batavorum, or cohors I Tungrorum. The mention of socks

(and underpants) strongly suggests the writer is a close relative or friend

whose concern for the recipient’s material comfort led him or her to send a

parcel from home. Even if socks and underpants were not standard issue,

provision of additional clothing of this kind is abundantly paralleled in the

papyri from Egypt. What is more, evidence of this sort promotes the commonsense

idea that Roman soldiers adapted to local conditions, however extreme. Finally,

it is interesting to note that the Chesterholm-Vindolanda texts show us how

swiftly auxiliary soldiers acquired literate habits and how proficient they

became in Latin, a language that was not their native tongue but their Roman

military service forced them to acquire. As a point of comparison, Charlemagne

was distinguished among his peers because he could write his name; however,

there is no evidence that he could read at all.

As a final point, cavalrymen could attach spurs, of iron or

bronze, to their caligae. Prick spurs had been worn by Celts of the La Tène

period, being evident in late Iron Age Gaulish and central European graves and

settlements, and were known in Greece from the late fifth century BC onwards.

They were sporadically used by Roman cavalry throughout the empire, especially

by troopers on the Rhine and Danube frontiers.

Body armour (lorica)

The Romans employed three main types of body armour: mail

(lorica hamata), scale (lorica squamata), and segmented (lorica segmentata) All

body armour would have been worn over some kind of padded garment and not

directly on top of the tunic. Apart from making the wearer more comfortable,

this extra layer complemented the protective values of each type of armour, and

helped to absorb the shock of any blow striking the armour. The anonymous

author of De rebus bellicis, an amateur military theoretician writing in the

late fourth century, describes the virtues of such a garment:

The ancients [i.e. the Romans], among the many things,

which… they devised for use in war, prescribed also the thoracomachus to

counteract the weight and friction of armour… This type of garment is made of

thick sheep’s wool felt to the measure… of the upper part of the human

frame…

The author himself probably coined the term thoracomachus

(cf. Greek thorâx, breastplate), which seems to be a padded garment of linen

stuffed with wool. One illustration on Trajan’s Column (scene cxxviii) depicts

two dismounted troopers on sentry duty outside a headquarters who appear to

have removed their mail-shirts to expose the padded garment.

Lorica hamata: Mail was normally made of iron rings,

on average about a millimetre thick and three to nine millimetres in external

diameter. Each ring was connected to four others, each one passing through the

two rings directly above and two directly below – one riveted ring being

inter-linked with four punched rings. The adoption of lorica hamata by the

Romans stems from their having borrowed the idea from the Celts, among whom it

had been in use at least since the third century BC, albeit reserved for use by

aristocratic warriors only. This early mail was made of alternate lines of

punched and butted rings. The Romans replaced the butted rings with much stronger

riveted rings, one riveted ring linking four punched rings.

The wearer’s shoulders were reinforced with ‘doubling’, of

which there were two types. One had comparatively narrow shoulder ‘straps’, and

a second pattern, probably derived from earlier Celtic patterns, in a form of a

shoulder-cape. The second type required no backing leather, being simply drawn

around the wearer’s shoulder girdle and fastened with S-shaped breast-hooks,

which allowed the shoulder-cape to move more easily. The shoulder-cape is indicated

on numerous grave markers belonging to cavalrymen, which also show the

mail-shirt split at the hips to enable the rider to sit a horse.

Although mail had two very considerable drawbacks – it was

extremely laborious to make, and while it afforded complete freedom of movement

to the wearer, it was very heavy, weighing anywhere between 10 and 15

kilograms, depending on the length and number of rings (at least 30,000) – such

armour was popular. A mail-shirt was flexible and essentially shapeless, fitting

more closely to the wearer’s body than other types of armour. In this respect

it was comfortable, whilst the wearing of a belt helped to spread its

considerable weight, which would otherwise be carried entirely by the

shoulders. Mail offered reasonable protection, but could be penetrated by a

strong thrust or an arrow fired at effective range. It was also vulnerable to

bludgeoning weapons such as clubs or maces. Worn underneath the lorica hamata

was undoubtedly some form of leather or padded protection, without which mail

was relatively useless, to dissipate further the force of a blow.

Lorica squamata: Scale armour was made of small

plates (squamae), one to five centimetres in length, of copper alloy

(occasionally tinned), or occasionally of iron, wired to their neighbours

horizontally and then sewn in overlapping rows to linen or leather backing.

Each row was arranged to overlap the one below by a third to a half the height

of the scales, enough to cover the vulnerable stitching. The scales themselves

were thin, and the main strength of this protection came from the overlap of

scale to scale, which helped to spread the force of a blow.

A serious deficiency lies in the fact that such defences

could be quite readily pierced by an upward thrust of sword or spear; a

hazardous aspect of which many cavalrymen must have been acutely aware when

engaging infantry. This weakness was overcome, certainly by the second century,

when a new form of semi-rigid cuirass was introduced where each scale, of a

relatively large dimension, was wired to its vertical, as well as its

horizontal, neighbours.

Scale could be made by virtually anyone, requiring patience

rather than craftsmanship, and was very simple to repair. Though scale was

inferior to mail, being neither as strong nor as flexible, it was similarly

used throughout our period and proved particularly popular with horsemen and

officers as this type of armour, especially if tinned, could be polished to a

high sheen. Apart from those to cavalry, most of the funerary monuments that

depict scale armour belong to centurions.

Lorica segmentata: This was the famous laminated

armour that features so prominently on the spiral relief of Trajan’s Column.

Concerning its origins, one theory suggests that it was inspired by

gladiatorial armour, since these fighters are known to have worn a form of

articulated protection for the limbs. Part of a lorica segmentata was found at

Kalkriese, the probable site of the Varian disaster in AD 9, making this the

earliest known example of this type of armour. It is last seen (in a carving)

sometime around AD 230 in the time of Severus Alexander – a good run, but of

only perhaps two-and-half centuries as opposed to the six centuries many book

illustrations and epic films (and, unfortunately, television documentaries)

would have us believe.

The armour consisted of some forty overlapping, horizontal

curved bands of iron articulated by internal straps. It was hinged at the back,

and fastened with buckles, hooks and laces at the front. As the bands overlapped

it allowed the wearer to bend his body, the bands sliding one over another. The

armour was strengthened with back and front plates below the neck, and a pair

of curved shoulder pieces. In addition, the legionary would wear a metal

studded apron hung from a wide leather belt (cingulum), which protected the

belly and groin. Round the neck was worn a woollen scarf (focale), knotted in

front, to prevent the metal plates from chafing the skin.

Superior to mail with regard to ease of manufacture and

preservation, but most particularly in view of its weight, this could be as

little as 5.5 kilograms, depending on the thickness of the plate used. It was

also more resistant to much heavier blows than mail, preventing serious

bruising and providing better protection against a sharp pointed weapon or an

arrow. Its main weakness lay in the fact that it provided no protection to the

wearer’s arms and thighs. Also full-scale, working reconstructions of lorica

segmentata have shown that the multiplicity of copper-alloy buckles, hinges and

hooks and leather straps, which gave freedom of movement, were surprisingly

frail. It may have been effective against attacking blows or in impressing the

enemy, but with its many maintenance problems we can understand why lorica

segmentata never became standard equipment in the Principate army.

Body shield (scutum)

Legionaries carried a large dished shield (scutum), which

had been oval in the republican period but was now rectangular in shape.

Besides making it less burdensome, the shortening of the scutum at top and

bottom was probably due to the introduction into the army of new combat

techniques, such as the famous Roman ‘tortoise’ (testudo), a mobile formation

entirely protected by a roof and walls of overlapping and interlocking scuta.

On the other hand, auxiliaries, infantrymen and horsemen alike, carried a flat

shield (clipeus), with a variety of shapes (oval, hexagonal, rectangular)

recorded.

Shields, scuta and clipi equally, were large to give their

bearer good protection. To be light enough to be held continually in battle,

however, shield-boards were usually constructed of double or triple thickness

plywood made up of thin strips of birch or plane wood held together with glue.

The middle layer was laid at right angles to the front and back layers. Covered

both sides with canvas and rawhide, they were edged with copper-alloy binding

and had a central iron or copper-alloy boss (umbo), a bowl-shaped protrusion

covering a horizontal handgrip and wide enough to clear the fist of the bearer.

An overall central grip was probably adopted from the Celts,

who certainly used such an arrangement at an early date. More specifically,

however, such a grip was to encourage parrying with the scutum and not, as

mentioned earlier in this book, the gladius. When the scutum was used

offensively, the horizontal handgrip allowed for a more solid punch to be

delivered as the fist was held in the correct position to throw a ‘boxing jab’.

It also meant that the legionary’s elbow was not over extended as the blow was

delivered. Such an arrangement, however, provided less balance to the scutum as

a whole. If, for instance, the scutum were struck above or below its central

plane, it would have been very difficult to prevent the shield from pivoting

upon its axis. The resulting movement would have thus created an opening in the

legionary’s defence. The vertical handgrip, on the other hand, was more

reliable in terms of blocking blows. The vertical orientation of the hand would

have enabled the legionary to keep the scutum as straight as possible, even if

the scutum were struck above or below the shield-boss. Of course, a less solid

punch can be delivered with the fist in a vertical position as compared to the

horizontal position.

When not in use shields were protected from the elements by

leather shield-covers; plywood can easily double in weight if soaked with rain.

Oiled to keep it both pliant and water resistant, the cover was tightened round

the rim of the shield by a drawstring. It was usual for it to have some form of

decoration, usually pierced leather appliqué-work stitched on, identifying the

bearer’s unit. A cavalryman had the luxury of carrying his shield obliquely

against the horse’s flank, slung from the two side horns of the saddle and

sometimes under the saddlecloth.

So much for the defensive equipment employed by the Romans.

Now we must turn our attention to their weaponry. Throughout our chosen period,

the main weapons in use were the bow, the sling, the javelin, the spear, the

sword, and the dagger. The first three were missile weapons, and the rest were

used in the close-quarter mêlée. We will examine each, in the Roman context of

course, in turn.

Shafted weapons

Few ancient civilizations eschewed the spear in their

arsenals, and in its simplest form, a spear was nothing more than a stout

wooden stick with a sharpened and hardened business end, the latter being

achieved by revolving the tip in a gentle flame till it was charred to

hardness. Beyond that, it was a long, straight wooden shaft tipped with a

metallic spearhead, although the sharpened stick with the hardened tip could be

quite an effective killing weapon too. Ash wood (as frequently mentioned in the

heroic verses of Homer and Virgil) was the most frequently chosen because it

naturally grows straight and cleaves easily. Moreover, it is both tough and

elastic, which means it has the capacity to absorb repeated shocks without

communicating them to the handler’s hand and of withstanding a good hard knock

without splintering. These properties combined made it a good choice for

crafting a spear.

Heavy javelin (pilum)

Since the mid-third century BC the pilum had been employed

by legionaries in battle as a short-range shock weapon; it had a maximum range

of thirty metres or thereabouts, although probably it was discharged within

fifteen metres of the enemy for maximum effect. The maximum range of any thrown

or shot weapon is irrelevant. Man is capable of running a sub-four minute mile,

but this does not mean the average man is so able. Similarly, it may be of

academic interest to know that a legionary was capable of launching a pilum

more than thirty metres. What is of greater interest is the fact that the enemy

had to be within twenty metres before the legionary had any real chance of

scoring a hit.

By our period the pilum had a pyramidal iron head on a long,

untempered iron-shank, some sixty to ninety centimetres in length, fastened to

a one-piece wooden shaft, which was generally of ash. The head was designed to

puncture shield and armour, the long iron shank passing through the hole made

by the head.

Once the weapon had struck home, or even if it missed and

hit the ground, the soft-iron shank tended to buckle and bend under the weight

of the shaft. With its aerodynamic qualities destroyed, it could not be

effectively thrown back, while if it lodged in a shield, it became extremely

difficult to remove. Put simply, the pilum would penetrate either flesh or

become useless to the enemy. Modern experiments have shown that a pilum, thrown

from a distance of five metres, could pierce thirty millimetres of pine wood or

twenty millimetres of plywood.

Continuing the practice of the late Republic, there were two

fixing methods at the start of our period, the double-riveted tang and the

simple socket reinforced by an iron collet. With regards to the tanged pilum,

however, there is iconographical evidence, such as the Cancellaria Relief and

the Adamklissi Monument, to suggest that a bulbous lead weight was now added

under the pyramid-shaped wooden block fixing the shank to the shaft. Presumably

this development was to enhance the penetrative capabilities of the pilum by

concentrating even more power behind its small head, but, of course, the

increase in weight would have meant a reduction in range.

Light spear (lancea)

Auxiliary foot and horse used a light spear (lancea) as

opposed to the pilum. Approximately 1.8 metres in length, it was capable of

being thrown further than a pilum, though obviously with less effect against

armoured targets, or retained in the hand to thrust overarm as shown in the

cavalry tombstones of the period.

Even though such funerary carvings usually depict troopers

carrying either two lancae or grooms (calones) behind them holding spares,

Josephus claims Vespasianus’ eastern cavalry carried a quiver containing three

or more darts with heads as large as light spears. He does not say specifically

where the quiver was positioned but presumably it was attached to the saddle.

Arrian confirms this in his description of an equestrian exercise in which

horsemen were expected to throw as many as fifteen, or, in exceptional cases

twenty light spears, in one run. Presumably infantrymen carried more than one

lancea; a low-cut relief recovered from the site of the fortress at

Mainz-Mogontiacum depicts an auxiliary infantryman brandishing one in his right

hand with two more held behind his clipeus. Analysis of the remains of wooden

shafts shows that ash and hazel were commonly used.

The simple term ‘spearhead’, however, embraces a great range

of shapes and sizes, complete with socket ferrules (either welded in a complete

circle or split-sided) to enable them to be mounted on the shaft and often

secured with one or two rivets and/or binding. Head lengths can vary from six

to eight centimetres all the way up to forty centimetres, whilst socket lengths

range from seven to thirteen centimetres in length. For use as a stabbing

weapon, practical experience tells us that the width of the blade was

important, for a wide blade actually prevents the spearhead from being inserted

into the body of an enemy too far, thus enabling the spear to be recovered

quickly, ready for further use. In our period of study the most common designs

were angular blades, with a diamond cross section, and leaf-shaped blades, with

a biconvex cross section.

Edged weapons

The modern infantryman is no longer armed exclusively with

the rifle and bayonet. His tactical repertoire has expanded to include hand

grenades, pistols, daggers, and sharpened entrenching tools. If he is a

specialist, he also masters a machine gun, a light mortar, or an anti-armour

weapon. The Roman legionary, on the other hand, was a specialist with one

weapon only, the gladius.

Short sword (gladius)

It would be a pointless sort of exercise to debate the

relative importance of the different swords of the fighting forces throughout

the period of Rome’s domination of the Mediterranean world, whether it was

single or double edged, short or long, heavy or light, straight or curved, and

so forth, which played the most vital rôle, but certain it is that, as Rome

expanded, the gladius was making an increasing contribution to the winning of

empire. Against the unarmoured formations frequently met with by Roman legions

it was a most potent weapon.

Of all the weapons man has seen fit to invent, the spear was

probably the one most universally used during our period of study. Not so,

however, with the Roman legionary, who was primarily a swordsman trained in the

science and skill of a very singular sword. It goes without saying that the use

of weapons has transformed man’s capacity to inflict violence. The capacity of

man-as-animal to deliver violence is very limited, as a psychologist

appropriately named Gunn describes vividly:

It is extremely difficult for one naked unarmed man to kill

another such man. He has to resort to strangulation, or to punching him hard

enough to knock him over so that he may gash open an important vessel with his

teeth, or break his head open by dashing it against the ground … Weapons

magnify the aggressiveness of a creature many times.

It had been back in the third century BC when the Romans had

adopted a long-pointed, double-edged Iberian weapon, which they called the

gladius Hispaniensis (‘Iberian sword’), though the earliest specimens date to

the turn of the first century BC. In our chosen period the gladius was employed

not only by legionaries, but by auxiliary infantrymen too.

Based on gladii found at Pompeii and on several sites along

the Rhine and Danube frontiers, Ulbert has been able to show that there were

two models of gladius, the one succeeding the other. First was the long-pointed

‘Mainz’ type, whose blade alone could measure sixty-nine centimetres in length

and six centimetres in width, and is well-evidenced in the period from Augustus

to Caius Caligula. The ‘Pompeii’ type followed this, a short-pointed type that

replaced it, probably during the early part of Claudius’ principate. This

pattern was shorter than its predecessor, being between forty-two and

fifty-five centimetres long, with a straighter blade 4.2 to 5.5 centimetres

wide and short triangular point. Whereas the ‘Mainz’ type weighed between 1.2

and 1.6 kilograms, the ‘Pompeii’ type was lighter, weighing about a kilogram.

The blade of both types was a fine piece of blister steel with a sharp point

and honed down razor-sharp edges and was designed to puncture armour. It had a

comfortable bone handgrip grooved to fit the fingers, and a large spherical

pommel, usually of wood or ivory, to help with counterbalance. In the hands of

the trained soldier it was a formidable instrument of destruction.

This sword lacked a typical cross hilt, which tells us it

was not a parrying weapon. There is little doubt, therefore, that the gladius

was designed primarily as a short-range thrusting weapon, that is, the

intention was to deliver the fatal blow by a thrust. Accordingly, the sword

blade was straight and the handle short, while the main design feature was the

point. The short length of the weapon allowed for ease of control, while its

comparative lightness enhanced the swordsman’s reaction time. It was weighted

more closely to the actual hilt than a standard sword so as to discourage the

slash and to encourage the thrust. This arrangement also helped to increase the

speed of the thrust. In addition, the oversized pommel increased the weight at

the back end of the sword, thus increasing the power behind the thrust.

Finally, the oval-shaped cross-guard just above the handgrip allowed the

swordsman to apply maximum pressure to the thrust, and this, combined with a

contoured grip to fit the hand snugly, increased the potency of the thrust. The

handgrip itself was some 7.5 to 10 centimetres in length, that is, slightly

longer than the width of a hand. This arrangement allowed for better efficiency

and control in weapon handling.

Unusually, legionaries and auxiliaries carried their sword

on the right-hand side suspended by the cingulum worn around the waist. The

wearing of the sword on the right side goes back to the Iberians, and before

them, to the Celts. The sword was the weapon of the high-status warrior, and to

carry one was to display a symbol of rank and prestige. It was probably for

cultural reasons alone, therefore, that the Celts carried their beloved weapon,

the long slashing sword, on the right side. Customarily a sword, when not in

the right hand, was worn on the left, the side covered by the shield, which

meant the weapon was hidden from view. However, the Roman soldier wore his

sword on the right hand not for any cultural reason. As opposed to a

scabbard-slide, the four-ring suspension system on the scabbard enabled him to

draw his weapon quickly with the right hand, an asset in close-quarter combat.

Inverting the fighting fist to grasp the hilt and pushing the pommel forward

drew the gladius with ease. More to the point, it also meant the sword arm was

not exposed when doing so.

For the Roman soldier, the gladius fitted his temperament

perfectly. It was a close-quarter weapon and the Roman was never one to stand

around, engaging in distant firefights, but rather he sought every opportunity

to engage his foe in a mêlée. Surely another sword type would never take the

place of the Queen of Death, the gladius.

Long sword (spatha)

Cavalrymen, on the other hand, used a longer, narrower

double-edged sword, the spatha, which followed Celtic types, with a blade

length from 64.5 to 91.5 centimetres and width from four to six centimetres.

The middle section of the blade was virtually parallel-edged, but tapered into

a rounded point. It was intended primarily as a slashing weapon for use on

horseback, and it usually was so employed, though the point could also be used

for thrusting if need be.

In spite of its length, the spatha was worn on the right

side of the body, as Josephus says, and numerous cavalry tombstones confirm,

suspended from a waist belt or baldric whose length could be adjusted by a row

of metal buttons. At the turn of the second century, however, the spatha

started to be worn on the left side, although not exclusively so.

Military dagger (pugio)

The pugio – a short, edged, stabbing weapon – was the

ultimate weapon of last resort. However, it was probably more often employed in

the day-to-day tasks of living on campaign. Carried on the left-hand side and

suspended on the same cingulum that carried the sword (though two separate

belts crossed ‘cowboy’ style was a dashing alternate), the pugio was slightly

waisted in a leaf-shape and some 20 to 25.4 centimetres long. The choice of a

leaf-shaped blade resulted in a heavy weapon, to add momentum to the thrust.

Like the gladius, the pugio was borrowed from the Iberians and then developed;

it even had the four-ring suspension system on the scabbard, characteristic of

the gladius.

The pugio, worn by legionaries and auxiliaries alike, was

obviously a cherished object. Soldiers seldom wasted time on aesthetics. Their

equipment, whether it belonged to an individual or to the state, remained

functional, the pila, gladii, scuta – all such equipage were primarily

utilitarian. Not so, it seems, the pugionis. The highly decorative nature of

Roman daggers of our period, and particularly their sheaths, suggests that even

common soldiers were prepared to spend considerable sums of money on what could

be classified as true works of art. Though remaining an effective fighting

weapon, the pugio was plainly an outward display of its wearer’s power.

Missile weapons

Bow

Whereas bows of self-wood construction were made exclusively

of wood in one or more pieces, the composite bow had an elaborate network of

sinew cables on its back to provide the cast, with a horn belly to provide the

recovery of the bow. The whole was built up on a wooden core with bone strips

stiffening both the grip and the extremities (the ‘ears’), and then covered

with skin or leather and moisture-proof lacquers. The back of the bow was that

side away from the archer, which was stretched in stringing and stretched even

more when the bow was drawn. The belly was the side nearest the archer when

drawn, which was compressed by stringing and compressed even more by drawing.

The design of a composite bow thus took full advantage of

the mechanical properties of the materials used in its construction: sinew has

great tensile strength, while horn has compressive strength. When released the

horn belly acted like a coil, returning instantly to its original position.

Sinew, on the other hand, naturally contracted after being stretched. This

method of construction and the materials employed thus allowed the bow to

impart a greater degree of force to the arrow when fired, compared with the

wooden self-bow of the same draw weight. This latter characteristic enabled the

archer to choose between two tactical options, depending on the need of the

moment. He either could deliver a lightweight projectile over a distance twice

what a wooden self-bow could shoot, or deliver a projectile of greater weight

or force at short range when the capacity to pierce armour or to thoroughly

disable an opponent was needed.

The actual range and performance of the composite bow is

open to debate, and a number of varied figures have been suggested. Vegetius

recommended a practice range of 600 Roman feet (c. 177 metres), while later

Islamic works expected an archer to display consistent accuracy at 69 metres.

Modern research tends to place an accurate range up to 50 to 60 metres, with an

effective range extended at least 160 to 175 metres, and a maximum range at

between 350 and 450 metres. Range is as much dependent upon the man as the bow

and coupled with this was bow quality – the better made the composite bow; the

more tailored to the individual archer’s height, draw weight and length, the

better the performance.

That is not to say that the composite bow was the ‘ultimate

weapon’. Draw weights of 150 pounds or more taxed even a very strong man and a

high rate of fire could not be sustained indefinitely. Unlike firearms or

weapons such as the crossbow, which store chemical or potential energy and, by

releasing this, propel their missile, a bow converts the bodily strength of the

firer into a force propelling the arrow. This skill is much harder to learn

than the use of a crossbow or a firearm such as an arquebus, which only has to

be loaded and aimed to be effective. Indeed, where a few hours sufficed to

teach an ordinary fellow to draw and aim a crossbow, many years of constant

practice and a whole way of life were needed to master the use of the composite

bow. Archery did not consist of a series of mechanical movements that anyone

could be trained to execute, but of a whole complex cultural, social and

economic relationship.

Other externalities to consider are those of the accuracy

and the effectiveness. The target’s size and rate of movement, as well as the

skill of the individual archer, governed accuracy. In actuality the archer

would have practised shooting at a stationary target. A trained archer, when

fresh, could get off six aimed shots in a minute with ease. Perhaps the best

modern estimate of his long-range accuracy comes from W.F. Paterson, himself an

experienced archer. Paterson concludes that a good shot on a calm day could be

expected to hit a target the size of a man on horseback at 280 yards about once

every four shots. At a hundred metres such an archer would have been able to

pick his man. At fifty he would have been sure of death.

However, whilst this level of accuracy – the ability to

pick-off individuals – would have been useful in the archer’s role as a

skirmisher his main task was to stand behind his own infantry and shoot,

indirectly, at a unit rather than an individual. In this case accuracy was more

concerned with all of the arrows arriving on the target area at the same time,

than with individual marksmanship. Thus, an effective shot was not necessarily

an accurate one, and in pitched battle a murderous barrage was possible even

without aiming.34 When Titus formed a fourth rank of archers behind three of

legionaries, these men could have had little or no opportunity of seeing their

target. They would have been firing blind, over the heads of the men in front,

hoping to drop their arrows down from a high trajectory onto the general area

occupied by the enemy and spread death and injuries amongst their ranks.

Arrow

The arrow penetrates because of the concentration of its

kinetic energy behind a narrow cutting edge. The types of arrowheads used by

the Principate army reflected these different penetrative requirements. Bodkin

heads or flat-bladed types were used for armour piercing, be the target shield

or body armour, acting on the same principles as the pilum. On the other hand,

trilobate, triple-or quadruple-vaned were more effective against unarmoured

horses and men. A bow relies on sending an arrow deep into the body of its

victim. As the arrow passes through it severs blood vessels and major arteries.

Since arrows ordinarily kill by bleeding, projectiles that could open up a

large wound on an unarmoured opponent were useful. A third category was

designed to carry incendiary material, such as a naphtha-soaked ball of twine

with wood splints. Five such arrowheads were recovered from the fort at Bar

Hill, Antonine Wall. They have three projecting wings that form an open iron

framework capable of holding inflammable material.

In terms of arrow technology heads were mainly tanged,

although the Romans also employed socketed types as well, and were glued and

bound to the shafts. The shafts were made from wood, cane or reed. The latter

is one of the best materials, having a combination of lightness, rigidity and

elasticity ideal for shafts. Reeds are also already well adapted to their

aerodynamic role as shafts by their need while growing to maintain an evenly

round profile to reduce wind drag, as well as by having the elasticity and

strength to bend and return to upright position. This latter adaptation is

critical as shafts need to be able to bend round the bow during shooting, and

flex so the tail swings clear of the bow before swinging back into line as the

arrow travels along the line it was aimed at the moment of release. Where cane

or reed was used the arrowhead was first attached to a wooden pile, which was

then glued onto a cane or reed shaft. The piles reduced the risk of the cane or

reed splitting on impact, which would, if it occurred, reduce the arrow’s

penetrative power. The remains of cane or reed arrows from Doura-Europos show

that the surface of the shaft was roughened and the fletching glued onto this

surface. The lower portions of three shafts actually bear painted markings, and

it has been suggested that the arrows were marked to identify their owners or

to denote a matching set.

Because human ribs are horizontal and the bow held

vertically, the head of a war arrow is often perpendicular to the plane of the

notch, so that the point may pass more easily between the ribs. For the same

reason, the plane of the head matches that of the notch in hunting arrows.

Modern experiments have shown that socketed arrows tended to break behind the

socket itself. Whether this action was deliberately intended or simply an

accidental by-product of manufacture is hard to ascertain. Tanged arrowheads

proved less likely to break on impact, the sinew binding required to hold the

head in place limiting their degree of penetration. These field trials were

conducted against all known forms of Roman armour. Not surprisingly, lorica

hamata proved to be the easiest to penetrate, followed by the lorica segmentata

and finally the lorica segmentata, in which none of the arrowheads penetrated

to a depth sufficient to cause a fatal wound even at a range of seven metres.

Somewhat surprisingly the wooden shield, especially if covered with leather,

almost provided as much defence.

Sling

Slingers normally served as a complement to archers; the

sling not only outranged the bow but a slinger was also capable of carrying a

larger supply of ammunition than an archer. Slingshots were not only small

stones or pebbles, but also of lead, acorn or almond shaped, and weighing some

eighteen to thirty-five grams. Unique to the Graeco-Roman world, these leaden

bullets, the most effective of slingshots, could be cast bearing inscriptions,

such as symbols – a thunderbolt emblem was popular – or a short phrase, usually

only a few letters. Some of these may be an invocation to the bullet itself or

invective aimed at the recipient – AVALE, ‘swallow this’. Doubtless the last

had a double meaning as the Latin term for lead sling bullet is glans (pl.

glandes), which literally means ‘acorn’ but can also refer to the head of the

penis. Other inscriptions, usually cut by hand in longhand writing rather than

impressed into the two-part moulds from which the bullets were made, bear

witness to the soldier’s jesting filth.

The sling itself, as deadly as it was simple, was made of a

length of non-elastic material such as rush, flax, hemp or wool. It comprised a

small cradle to house the bullet, and two braided cords, one ending in a knot

and the other with a loop. In all techniques of slinging, the slingshot was

placed in the centre of the cradle, the loop was secured to the second finger

of the throwing hand and the knot between the thumb and forefinger of the same

hand. In the Mediterranean world the common casting technique was the horizontal

whirl, as described by Vegetius. The sling was held with the throwing arm

raised above the shoulder. The slingshot was placed in the cradle, and the hand

and sling allowed to drop backwards over the head, and whirled around the head

clockwise (from the slinger’s point of view) a number of times (Vegetius only

allows a single whirl around the head) until sufficient momentum was built up.

The knot was then released perpendicular to the body so the slingshot flew out

straight ahead, its range being related to the angle of discharge, the length

of the whirling cords and the amount of kinetic energy imparted by the thrower.

The potential range of the sling has been a the subject of

considerable debate and speculation. The problem lies with the testimony of the

soldier-scholar Xenophon, who claimed that the leaden missiles of the Rhodian

slingers carried ‘no less than twice as far as those from Persian slings’, the

latter slinging a stone ‘as large as the hand can hold’. The more conservative

estimates are around the 200 metres mark, while 350 metres, 400 metres, and

even 500 metres, have been suggested as possibilities for the maximum range of

a leaden bullet. On the practical side, Korfmann observed for himself Turkish

shepherds, males who grew up in a sling-using milieu, sling ordinary pebbles.

In five out of eleven trials the pebbles reached 200 metres, and three of the

best casts were between 230 and 240 metres.

Fast-moving slingshot could not be seen in flight and did

not need to penetrate armour to be horrifically effective. Vegetius writes that

slingshot was more effective than arrows against armoured soldiers in armour,

since they did not need to penetrate the armour in order to ‘inflict a wound

that is still lethal’. A blow from a slingshot on a helmet, for instance, could

be enough to give the wearer concussion.