During the night of 14–15 September 1941, seventy years after Prussia’s titanic victory over the French at Sedan, the armored spearheads of two German armies met at Lokhvitsa, 120 miles east of Kiev, forming an iron ring around 1.6 million Soviet troops. In what turned into the greatest battle of annihilation in recorded human history, the German Wehrmacht destroyed four entire Soviet armies and most of two others, inflicting one million casualties and capturing 665,000 Soviet soldiers.

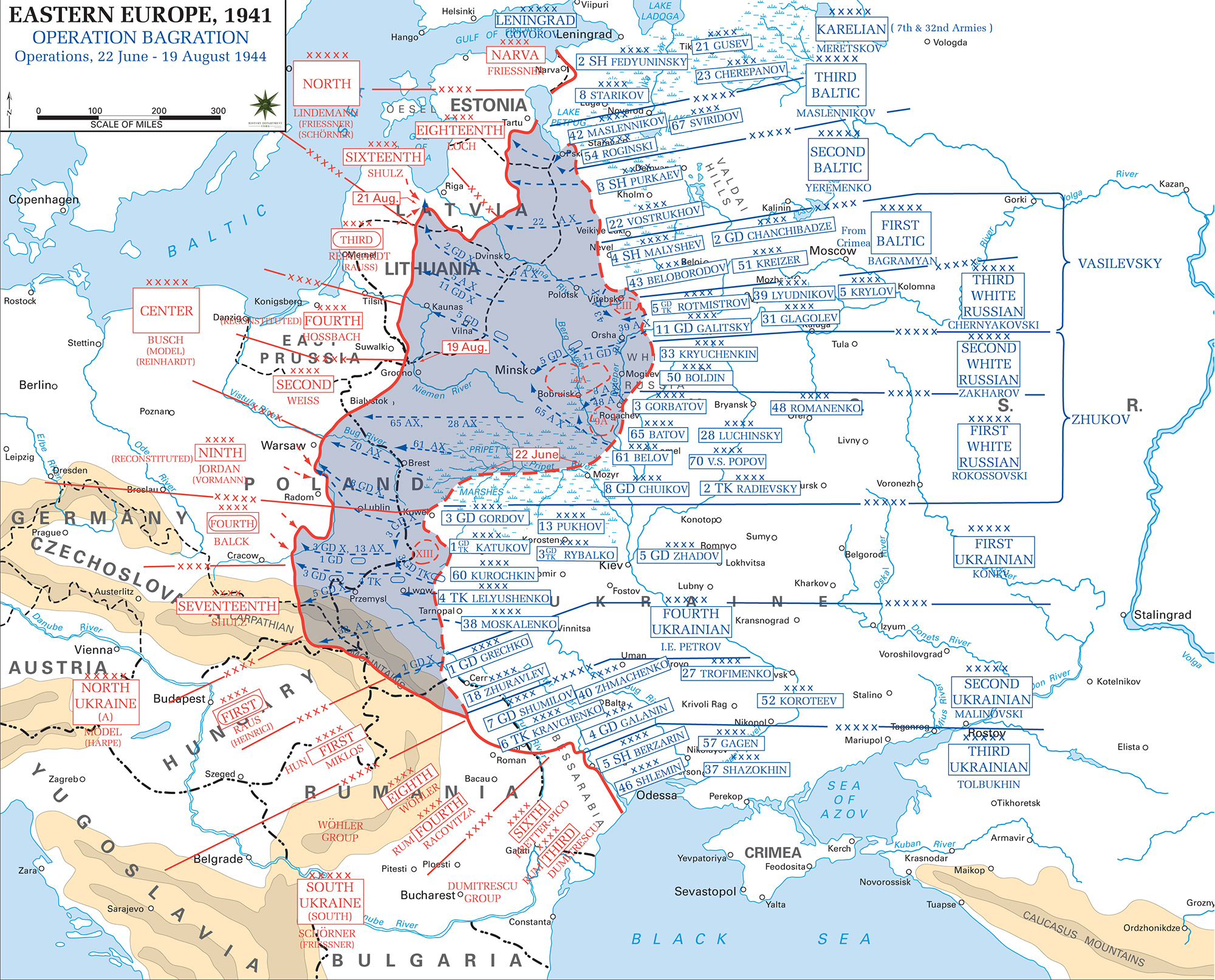

Less than three years later, on 22 June 1944, the third anniversary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, 2.5 million Soviet troops launched an offensive, striking Germany’s Army Group Center along a 360-mile front extending in a great semicircle from Mozyr on the Pripyat River to Polotsk on the Dwina River. For the first time since the Nazi-Soviet war began, the attacking Soviet forces enjoyed unchallenged control of the airspace over the battle area.

Without interference from the German Luftwaffe, Soviet armored spearheads advanced over 125 miles in less than 12 days. By the time the Soviets recaptured Minsk on 3 July, 25 divisions and 250,000 troops had vanished (killed, wounded, or missing) from the German order of battle, and Army Group Center ceased to exist. Soviet premier Joseph Stalin celebrated his greatest victory over the Wehrmacht on 17 July 1944 by marching a column of 57,000 German prisoners of war led by their captured generals through the streets of Moscow.

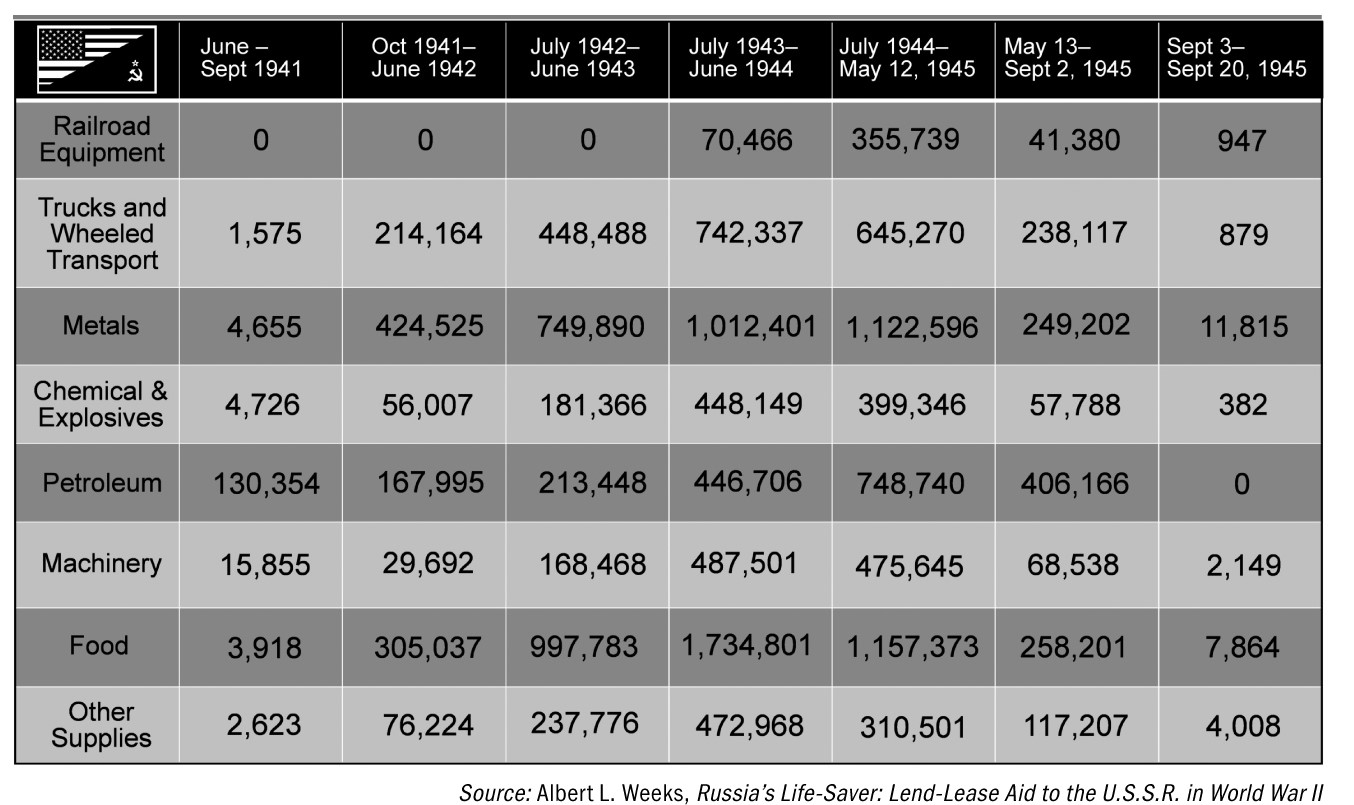

Meanwhile, like the French generals in May 1940, the German High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW) was reduced to drawing halt lines on maps—lines that advancing Soviet forces had already passed. Unable to suspend his disbelief in the unfolding catastrophe, German chancellor Adolf Hitler continued to count on the exhaustion of Soviet troops and supplies to put an end to the Soviet offensive, but American lend-lease programs provided the Soviets with thousands of trucks, jeeps, and wheeled transports to carry the supplies and replacements that kept the Red Army moving forward.

British prime minister Winston Churchill understood what had happened, exclaiming in horror to his private secretary, “Good God, can’t you see that the Russians are spreading across Europe like a tide; they have invaded Poland and there is nothing to prevent them marching into Turkey and Greece!” Transformed Soviet military power had not only destroyed Germany’s last strength in the east, but the collapse of German military power also meant the Red Army would reach Berlin long before the Anglo-American forces could do so. Once Stalin’s armies conquered central and eastern Europe, they would not leave, extending communism’s conflict with the West to the heart of Europe.

For Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the question during World War II was always how to end the war as quickly as possible at the lowest cost in lives. In 1944, the Anglo-American alliance was still troubled by the chronic fear of bold, offensive operations that might expose British and U.S. forces to heavy casualties. A sudden spike in casualties could cause popular support for the war inside the Western democracies to collapse.

In the Soviet Union, conditions were different. Stalin’s totalitarian state exerted absolute control over its enslaved population, its armed forces, and its generals. Soviet casualties were never Stalin’s concern. Long before Nazi concentration camps existed, Soviet security forces maintained camp systems that consumed an estimated 17 million lives. The issue for Stalin, then, was fundamentally different: how to organize and direct the Soviet state’s masses of humanity and warfighting equipment against the Nazi invader to ensure that before the war ended, Soviet armies would control as much of Europe and the Eurasian land mass as possible.

How the triumphant Wehrmacht of 1941 was crushed in 1944 is a story of two different military transformations. The first was a German transformation that focused on marginal, tactical changes to an existing World War I army; the second was a Soviet transformation focused on integrating and concentrating combat power on the operational level for strategic effect. Of the two, the Soviet transformation produced a decisive margin of victory. By 1944, the Soviet military leadership had fundamentally transformed warfare through the integration of ground maneuver forces with the dramatic increase in the size and power of Soviet strike (artillery and airpower) forces—a revolution in warfare that created a dramatic imbalance in military power between Soviet and Nazi forces.

PRELUDE TO WAR: THE GERMAN TRANSFORMATION

Why the German army invaded Russia in June 1941 with more horses than tanks is a curious tale. After all, by the end of the nineteenth century, Germany was a world leader in fusing science and technology, a comparative advantage that should have delivered decisive results in war. Understanding why this did not turn out to be the case involves understanding that a German military designed from its inception for short, decisive campaigns in central and western Europe was incapable of waging war over hundreds of thousands of square miles in a bitter, unforgiving climate. In this sense, the destruction of Army Group Center in 1944 was the culminating event in a process that began before the first German soldier set foot inside the Soviet Union.

In the aftermath of World War I, the answers to the first-order questions—where, whom, and how does the German army fight?—were fairly straightforward. The mission for the army was to develop the military means to ensure that in a future regional conflict or crisis, Germany could reach a quick operational decision through rapid decisive maneuver before its presumed opponents—France, Poland, and Czechoslovakia—could be reinforced with troops and resources from Great Britain.

What the German military leadership wanted were the tactical means to avoid a destructive war of attrition, a form of warfare that nullified the sheer fighting quality of German forces and sapped the economic and moral strength of the German people. The idea of waging total war to make Germany a world power was absent from German strategic thinking. Germany’s strategic aims were limited to regaining lost territory and reestablishing itself as Europe’s leading military, political, and economic power. In the German military mind, restoring tactical mobility to warfare promised to reinvigorate a traditional Prussian-German way of war, not to create a fundamentally new kind of warfare.

Colonel General Hans von Seeckt, appointed army chief of staff in 1919, was a co-architect of German national strategy. When he assumed his duties, the painful experience of running out of able-bodied men in the last year of World War I was fresh in his mind. The commander of Germany’s new 100,000-man army and the leader of its clandestine general staff (an organization forbidden under the terms of the 1919 Versailles Treaty) harbored no illusions regarding Germany’s fatal disadvantage in resources compared with Great Britain, France, and the United States.

Within months of the armistice’s signing, von Seeckt directed three hundred German officers to examine the army’s wartime strategic, operational, and tactical failures and successes. Von Seeckt was not interested in the kind of self-congratulatory after action reviews that pass for lessons learned in the contemporary American military establishment. Von Seeckt insisted on fact-based, gut-wrenching analysis. He got results. The resulting report provided detailed analyses of the successful tactical innovations that von Seeckt requested. The most important innovations entailed the phased integration of artillery strikes equivalent to the firepower of several hundred B-52 bombers with small infantry assault groups or storm troops. The assault groups infiltrated enemy defense lines, probing for weak points and bypassing strong points. Of special interest were General Erich Ludendorff’s spring 1918 offensives—masterful operations that had employed the tactics of integrated fire and maneuver, driving a wedge between the French and British armies and advancing to within thirty-seven miles of Paris.

Numerous studies and discussions sought to answer several critical questions. Why had the integration of devastating artillery fire with infiltration tactics worked but Ludendorff’s offensives had failed? Why did Ludendorff not reinforce battlefield success where it occurred instead of clinging to a mechanistic plan his Prussian predecessors would have abandoned after the first shot? Ultimately, the same question was raised repeatedly: how could attacking German forces sustain the momentum of the initial assault and exploit success to achieve a breakthrough in depth from which the opponent could not recover? Answering these questions led the postwar German army in the 1920s to adopt the leadership style, tactics, organization, and equipment that would eventually provide the basis for what Western observers would call blitzkrieg, or lightning war.

The idea of exploiting new training, leadership, and technology to achieve superior fighting power at the decisive point, or Schwerpunkt, took hold. Officer accessions were reoriented to recruit and develop a new generation of leaders who could command under more fluid conditions of warfare and changing technology. The postwar German military leadership set out to attack the problem of command and control in future war from a new angle.

Since the technologies of telephone and radio could not confer omniscience on senior commanders remote from the action, battlefield commanders were needed who could work with broad tasking orders and use their own initiative to seize opportunities. Recognizing that a system of battlefield opportunism could only work if it rested on a cultural foundation that rewarded initiative and innovation at every level, the German military leadership stressed quality over quantity in manpower and the importance of soldier education, physical fitness, and training to cultivate initiative in battle.

The value of aircraft, particularly to attacking ground forces, was widely acknowledged, but the concept of mobile warfare spearheaded by tanks and armored infantry was still treated with skepticism. The traditional focus on short, decisive campaigns obviated the logistical problem of sustaining operations over vast distances and for long periods, an oversight that would eventually plague the German army in Russia. A significant number of senior generals strongly opposed programs designed to equip the German infantry with increased mobility and firepower. Instead, they clung tenaciously to the large, slow infantry divisions that marched into battle during World War I.

While von Seeckt fought these battles inside the army, he also pressed the German government for a policy of rapprochement with the Soviet Union, an act that led to the Treaty of Rapallo.Signed on 16 April 1922, the treaty normalized relations between Moscow and Berlin. It did not include secret provisions for military cooperation with Germany, but at the instigation of von Seeckt, such cooperation commenced almost immediately.

Rapprochement with the new Bolshevik state not only strengthened German security, it also achieved von Seeckt’s goal of reconciling Germany’s need for new military technology with the development of new concepts of warfare in a period of severely constrained defense spending. By trading German technology and military assistance for space inside Russia to develop and test new German military equipment, including tanks and aircraft, von Seeckt’s secret arrangements with the Soviet Union skillfully circumvented the provisions of the Versailles Treaty.

The German army and air force that emerged from von Seeckt’s reforms were not everything he wanted. The army still reflected the preferences of Germany’s military elites and their underlying Prussian military culture: a small, elite professional military force around which larger German reserve forces would assemble in time of war.

Military modernization was still partial, not total. Horse cavalry and horse-drawn artillery and logistical support remained an unavoidable necessity for a nation heavily in debt with an industrial base struggling under the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty and, eventually, a world-wide economic depression. Neither von Seeckt nor his officers considered wholesale modernization to be possible or, frankly, necessary. After all, neither he nor they perceived any strategic advantage to be gained from an invasion of the Soviet Union. Rightly or wrongly, most Germans saw the Russians as allies that had fought with them to rid Europe of Napoleon. In the wars of unification, Otto von Bismarck secured Russia’s support to found the second German Empire. Only the German Social Democrats were historically anti-Russian for ideological reasons.

As a result, the German army Hitler inherited in 1933 was a traditional Prussian-German military institution focused on decisive battles of encirclement and annihilation in central and western Europe, an army enabled by the technologies of mobility, aviation, and increased firepower, but not a revolutionary force. Hitler’s decision to rapidly expand the German army into a mass conscript force did not fundamentally alter this outcome. Despite Hitler’s interest in tanks, until 1939 there was no definitive proof in his mind that mobile armored firepower operating in close coordination with airpower justified the expense of building more than a few armored (Panzer) divisions. The events of 1939–1940 changed Hitler’s opinion.

After the fall of France in 1940, not even the German general staff continued to question the decisive use of armored, motorized, and air forces to turn a tactical advantage into a strategic one by dislocating the enemy’s force and paralyzing its command structure. At the same time, neither Hitler nor his Western opponents realized that Germany’s stunning victories in the West concealed serious deficiencies in the Wehrmacht’s structure and equipment.

In 1940, the quality of German armor was actually inferior to that of the tanks and armored vehicles in the British and French armies. Superior doctrine, tactical leadership, and soldiering—combined with the skilled, operational concentration of armor and its revolutionary integration with supporting tactical airpower—compensated for the shortcoming. The Luftwaffe was also far ahead of Soviet, American, and British air forces in terms of a coherent doctrine for conducting joint operations with the army. Until the Allies and the Soviets caught up in 1944, German air-ground integration created a strategic impact.

Waging war in the West with a partially transformed army worked, but it was still a near-run occurrence. Weaknesses in British and French organization and command structures worked to German advantage; had the British and French forces operated differently and Hitler’s Western offensive had failed, Germany would have been plunged into a long war at a point when it had almost no significant equipment stocks or reserves. In fact, without the influx of Soviet raw materials and fuel made possible by Hitler’s 1939 nonaggression pact with Stalin, Hitler’s 1940 offensive in the West might not have happened at all.

A year after the fall of France, Germany’s armed forces were still not designed to launch attacks over 1,000 miles—the distance from Berlin to Moscow—let alone eventually defend a front of 1,200 miles, roughly the distance from Boston to Miami. The Luftwaffe had only 838 bombers in Russia, half the number that was available for the 1940 campaigns, because German air assets were still dealing with the threat from Britain.

In 1941, the severe shortage of aircraft of all types because of ongoing operations against Britain left advancing German armor without the reconnaissance and strike aircraft it needed, while the shortage also severely restricted the Luftwaffe’s ability to interdict Soviet rail lines transporting manufacturing equipment to the Urals. But these were not the only problems that plagued the German war effort.

From the moment he took power, Hitler was ideologically committed to the creation of a new national leadership cadre headed by men who, like him, had working-class origins. Hitler loathed the old elites who dominated German society. He cleansed the German officer corps of anyone who questioned or challenged his regime and rewarded those who were loyal Nazis or obedient technocrats, but he was still compelled to rely on Germany’s elite classes to run the armed forces and society more than he liked. Hitler quietly discarded the Prussian principle requiring German general staff officers to provide written expressions of opposition to orders that were judged wrong and replaced it with National Socialism’s demand for unconditional obedience to all orders. However, it was really Hitler’s promotions and gifts of cash to Germany’s military elites that guaranteed their loyalty to the Nazi state. Hitler’s generosity turned Germany’s new crop of field marshals and colonel generals into rich men.

Hitler also employed a type of affirmative action program so he could install his working-class comrades and party loyalists in power throughout German society. The effect was a managed or command economy shaped by military priorities but run by a coalition of government bureaucrats, party hacks, and greedy industrialists. During the first two years of war, this defective combination produced widespread duplication of effort, waste, and poor distribution.

Hitler rose to power on the promise of a better life for the average German, and he aimed to keep that promise. In the spring of 1942, 90 percent of Germany’s defense industries were still working on a single shift basis. Moreover, Hitler’s desire to spare the German people the hardship of war meant that far too much of German industry and labor were engaged in producing consumer goods. The multiplicity of competing government bureaucracies and the military’s demand for highly engineered, technically complex weapons systems compounded these deficiencies in defense needs by obstructing cheaper, faster methods of mass production. Lieutenant General Hermann Balck, an officer who commanded in Russia, Italy, and France, described the disastrous impact of this problem on his division:

Our worst problems in weapons development and production came from the interference of all those lackeys around Hitler and from the influence of the industry. The industry, of course, was only interested in what their position at the end of the war would be. As a result, it proved impossible to achieve standardization or a rational choice of vehicles, both armored and unarmored. The situation when I took over command of my division [the 11th Panzer Division] in Russia was so bad with respect to diversity of vehicles that I felt I had to write a very strong letter to Hitler from the front. This letter dealt with the necessity to take over the industry, to get real control over it and to standardize vehicles and engines in some reasonable way. As it turned out, Hitler was never able to gain control over the industry.

In the spring of 1942, German minister of armaments Albert Speer and Luftwaffe general Edward Milch cooperated to persuade Hitler of the need to revolutionize German war production by using existing resources more efficiently. Hitler approved their recommendations, and the impact was immediate and significant. Within months, the German aircraft industry was producing 40 percent more aircraft than it had in 1941 with only 5 percent more labor and substantially less aluminum.

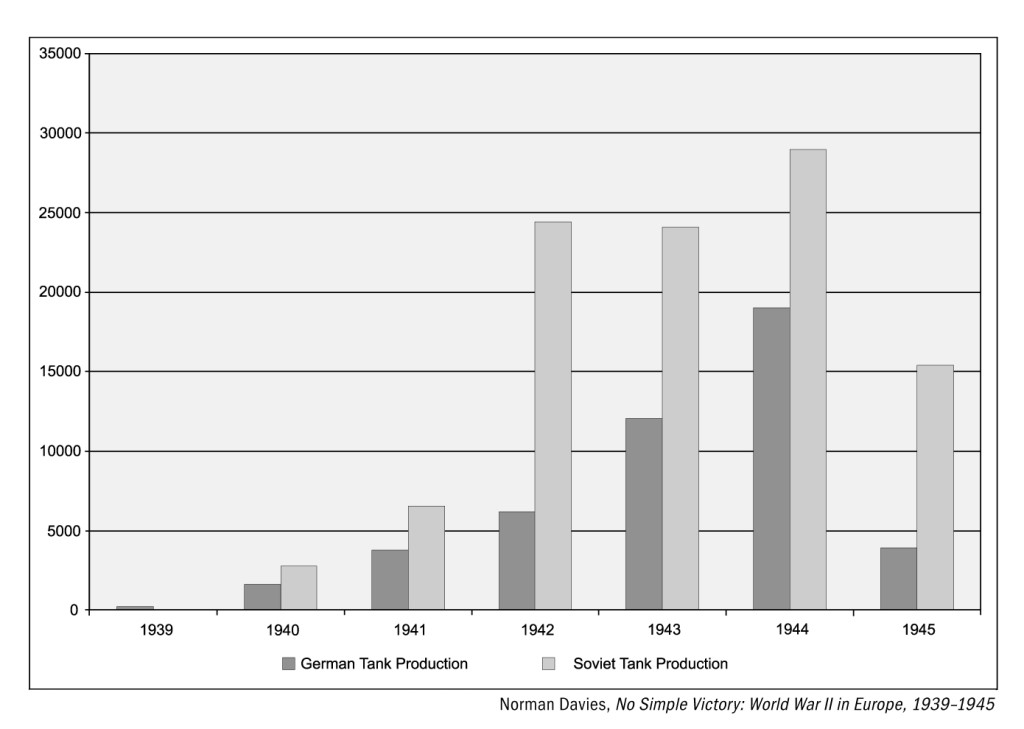

By 1943, Germany’s annual military aircraft production rose from 14,700 to 25,200, and in 1944, it rose again to 37,000—more aircraft than were being produced in the Soviet Union. Tank production also rose from 2,200 armored vehicles of all types in 1941 to 11,000 medium tanks and assault guns, 1,600 tank destroyers, and 5,200 heavy tanks—in all, 17,800 medium tanks and assault guns in 1944, an impressive figure, but one that fell short of the Soviet Union’s output.

In 1941, this level of output would have conferred a decisive advantage on the German Wehrmacht in Russia, even to the point of securing German victory in the east before January 1942, but the equipment came too late for the worn-down German forces of 1944.41 Germany’s allies—Italy, Finland, Hungary, and Romania—also offered the potential to deploy significant forces and production capability to support the German war effort, but their collective potential was ignored or mismanaged by the Nazi state throughout the war.

German and Soviet Annual Tank Production, 1939–45

Hitler and his generals ignored the great paradox that “an advancing army could march from victory to victory, smashing every enemy concentration in its way, but it had to recognize that every step forward dulled its fighting edge, robbing it of precisely those qualities that made it formidable in the first place.” In the late summer of 1942, Hitler’s forces were already so overextended that some German soldiers actually died of starvation in the front lines.

By 1944, waging war in the vastness of the Soviet Union had consumed men and matériel faster than the Nazi state could replace them. Confronted with superior forces on every side, Germany could do little more than replace the matériel that was lost in combat. In the air, the demand for fighter aircraft to defend German cities from the Anglo-American bombing campaign denuded Luftwaffe strength. In April, the Luftwaffe fighting in Russia had only 500 combat aircraft to counter 13,000 Soviet planes. By the summer of 1944, the Wehrmacht’s strength in the east fell to 2,242,649 troops—the lowest total since June 1941. In the front lines opposing the Wehrmacht were 6,077,000 Soviet troops.

THE SOVIET TRANSFORMATION AFTER WORLD WAR I

Once the Communist Party consolidated its power over tsarist Russia, Soviet military leaders such as Sergei Kamenev, Georgii Isserson, Aleksandr Svechin, Abram Vol’pe, Mikhail Frunze, and Mikhail Tukhachevskiy debated the meaning of Russia’s military failures in World War I and the Red Army’s defeat in its first invasion of the West in the Polish-Soviet war in 1921. Soviet studies of World War I revealed a preference in Russian minds for the Brusilov offensive of June through December 1916 and the Anglo-French offensive at Amiens in August 1918. Both involved the systematic preparation of the offensive theater, which included the assembly of operational reserves and the establishment of logistical support centers in depth. In the years leading up to World War II, marshalling military power to overwhelm the opponent at key points became the organizing imperative for planning and executing large-scale Soviet offensive operations. For the participants in the debates that lasted for nearly a decade, these experiences administered several critical lessons. The future keys to victory seemed to depend on operational pauses and the regrouping of forces, the concentration of strategic reserves, technical competence, and the logistical preparation of whole regions for the transport and provisioning of attacking forces.

When the time came to formally define warfare in Marxist-Leninist terms, the answer was straightforward: “total war.” The notion of a partial military transformation on the model of the Germans or the plans of J. F. C. Fuller was considered but rejected as an inherently bourgeois concept unsuited to the needs of Soviet communism’s world revolutionary movement. Instead, postwar Soviet thinking created the intellectual and industrial foundations for a massive military machine designed for offensive warfare and manned by troops trained, equipped, and ideologically hardened for sweeping maneuver over vast distances.

The resulting theory of future war employed mechanized formations composed of tanks, motorized infantry, and self-propelled guns within the framework of “deep operations,” the idea of striking deep into the enemy’s rear areas. Deep battle emerged as an overarching concept designed to exploit the mobility of mechanized and armored forces to outflank and encircle enemy forces. Soviet operational art embraced “all arms” combat, which meant the use of aviation formations with mechanized and airborne forces that could be delivered in the enemy’s rear areas. This approach contributed to the overall Soviet strategic goal of dissolving the opposing forces’ capacity for defense.

In 1930, the Soviet military theory of combined arms formations that could engage in multi-echeloned offensives was formally approved by Stalin. He deliberately harnessed the first five-year plan, which had begun in 1928, to the militarization of the Soviet Union’s national economy. From 1929 onward, Stalin ensured that “80 to 90 percent of [Soviet] national resources—raw material, technical, financial, and intellectual—[were] used to create the [Soviet] military-industrial complex,” converting Soviet society into a war mobilization state.

By the summer of 1935, by which time millions of people in the Ukraine had already been deported or murdered through systematic starvation or shooting, industrial expansion had increased the Soviet army to more than 940,000 troops. Factories turned out more than 5,000 tanks, 100,000 trucks, and 150,000 tractors, motorizing 3 rifle divisions, the heavy artillery of the army’s main reserve, and much of the Soviet army’s anti-aircraft artillery. Then, Stalin suddenly unleashed a campaign of terror that eventually consumed 5 million more lives inside the Soviet Union.

From exile in Mexico, Leon Trotsky, Stalin’s enemy in the world communist movement, called for a popular revolt to remove Stalin from power. Because Trotsky was the architect of the Red Army, Stalin reasoned that the ranks of the armed forces had to be purged of any lingering Trotskyite elements. Of course, with the exception of Mikhail Tukhachevskiy, one of Trotsky’s colleagues, and a few other senior officers, Stalin did not know most of the 35,000 Soviet military officers (including numerous generals, admirals, and colonels) whom he had executed. Stalin’s foremost concern was to eliminate any potential alternative to his own absolute power.

Not everyone with a promising intellect perished, but Stalin’s purge killed most of the Soviet military’s conceptual thinkers, placing men who had recently been lieutenants in command of regiments and colonels in command of armies. New officers rose to fill the vacant ranks—men such as Georgii Zhukov, who read very few books, distrusted foreigners, believed in iron discipline, and applauded Stalin’s violence against the “class enemy.”

By early 1941, this new generation of Soviet officers was leading troops inside a force that had increased in size to 4,207,000 men. This prewar force was already larger than the German Wehrmacht that would invade the Soviet Union six months later. In addition, the Soviet armed forces possessed far more tanks and aircraft than the attacking German forces: 14,200 Soviet tanks (1,861 of which were heavily armored and up-gunned T-34s and KVs) versus 3,350 German tanks, and 9,200 Soviet aircraft to Germany’s 2,000.

These points notwithstanding, Stalin, like Hitler in 1939, harbored serious doubts about tanks. These doubts led him to reject the brilliant concepts and innovative ideas of the men he executed. The upshot was that in June 1941, Soviet tanks were still widely dispersed, not concentrated for decisive operations. Even more troubling, only about 80 percent of the tanks in the Soviet army’s 9 mechanized corps formations were operational at any given time. Despite the large numbers of aircraft, only 15 percent of Soviet pilots were trained to fly at night. As a result, when Operation Barbarossa began, not one of the Soviet army’s 170 divisions and 2 brigades in the Western military districts bordering Germany, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania was up to full strength.

The disaster that ensued in the wake of Hitler’s invasion in June 1941 came close to destroying Stalin and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Ultimately, it was not the Soviet armed forces but rather the vast distances, severe winter weather (with temperatures sometimes falling below -30° Fahrenheit), and woeful inadequacy of German equipment stocks and repair parts that saved Stalin and the Soviet Union from destruction. Thanks to the Wehrmacht’s inability to exploit its victories before the close of 1941, Stalin’s war mobilization state survived to support a crash modernization program that organized and equipped new formations and redeployed Soviet forces from the Far East to the west. The result was impressive. In December 1941, the Soviet army mobilized 291 divisions and 94 brigades, a force of 4 million men—again, a force larger than the invading Wehrmacht.

Through 1941 and 1942, a series of crushing defeats and the loss of valuable territory and millions of lives compelled Stalin and his generals to finally reinvigorate the concepts and ideas developed in the 1920s and 1930s. Survival was not easy, and lessons were not learned quickly.

As late as November 1942, a massive Soviet offensive involving nearly 700,000 troops and 2,000 tanks against Germany’s numerically inferior Army Group Center in the Rzhev salient, about 130 miles west of Moscow, failed miserably, costing Soviet forces at least 350,000 casualties. It would take time before new formations of self-propelled anti-tank artillery, engineers, mortars, and anti-aircraft guns, along with heavily armored T-34 and T-70 tanks, were added to tank and mechanized brigades. Stalin’s resistance to fundamental reform postponed the formation of tank armies composed exclusively of tanks until late 1942, a concept first contemplated in the early 1930s by many of the men Stalin’s purges swept away. But in early 1943, the appearance of 5 “tank armies,” new armored shock forces, had an immediate and dramatic impact on the Wehrmacht.

By the standards of the superbly trained German army, Soviet tactics were often crude, even clumsy. Soviet troops were poorly educated and culturally disinclined to independent action. Russia had long been a place of petrified servitude where tens of millions of eastern Slavic peasants lived and worked on vast estates belonging to Russia’s ruling classes. Forced labor was common, and the individual Russian undertook no action of consequence without the sanction and direction of the Russian state.

This cultural condition compelled the Soviet military leadership to make virtue of necessity. Unconditional obedience to orders at the lowest level often cost lives, but it also enabled strategic deception, as well as the rapid assembly of large air and ground forces on the operational and strategic levels. Steady improvements to the transportation and manufacturing infrastructure, much of which was beyond the reach of Germany’s limited airpower, after November 1941 facilitated the deployment of armies and groups of armies across the front with real operational and strategic effectiveness. Ruthless discipline combined with the Soviet high command’s (Stavka’s) ability to mobilize and direct resources wherever it chose created unrivaled lethality. Simplicity and rigidity on the tactical level translated into operational agility with strategic effect.

Any deviation from the plan by a single corps, division, regiment, or even rifle battalion could disrupt the entire operation. Therefore, front and army commanders discouraged “excessive” initiative by their subordinates lest they disrupt the overall offensive. As a result, throughout the war, the rifle forces and their supporting arms assigned to its operating fronts and armies, which constituted 80 percent of the Red Army, resembled a massive steamroller flattening a path through the Wehrmacht’s defenses regardless of human cost. Casualties were highest when the steamroller faltered, but they were also high when it accomplished its deadly mission.

Put differently, the Soviet command and control structure that mounted operations to break through Wehrmacht defenses and strike deep into German rear areas was a highly centralized, top-down, attrition-based, industrial meat grinder that squandered human life and resources on a scale that is beyond Western comprehension. To ensure the meat grinder’s effectiveness, when Soviet commanders failed or disobeyed, Stalin simply executed them, something Stalin’s top commanders never forgot.

Yet as horrifying as the steamroller was, without the machinery of terror that could wage total war—as much against Russia’s own soldiers and peoples as against the Wehrmacht—Stalin and the Communist Party would not have survived the war.70 On its own, Russian nationalism and distaste for Hitler’s theories of racial superiority that presented Slavs as inferior Untermenschen (sub-human) were not enough to recruit the huge numbers of soldiers required for the meat grinder, Stalin’s war machine.

Stalin’s decades of mass murder, deportation, and collectivization inside the Soviet Union had the effect of creating substantial resistance to his regime. One angry Russian woman summed up Stalin’s strategic dilemma very well: “Shoot me if you like, but I’m not digging any trenches. The only people who need trenches are the communists and Jews. . . . Your power is coming to an end and we’re not going to work for you.”

As self-defeating as Hitler’s policies and the criminal acts they inspired were, the policies were unevenly applied and sometimes ignored. In September 1942, the German Sixth Army fighting in Stalingrad had over 50,000 Russian and Ukrainian auxiliaries attached to its front line divisions, representing over a quarter of the divisions’ fighting strength. Had Hitler turned the National Socialist crusade against Bolshevism into a war of liberation, the outcome of the war in the east would likely have been different.

After the United States’ entry into the war, President Franklin Roosevelt’s lend-lease program provided the Soviet Union with much of the logistical support and transport it needed to move forward. Then, on 6 June 1944, American and British forces massed 6,000 ships and 11,000 aircraft to carry nearly a million men and thousands of tanks and self-propelled guns to Normandy. Within weeks, the Allied numbers inside the Normandy beachhead grew to 850,000 troops and 154,000 vehicles and drew an increasing number of German combat formations away from the eastern front.

With the Wehrmacht exhausted by its own exertions, the stage was set in 1944 for a dramatic turning point in the east. “No one,” wrote Marshal Georgii Zhukov in the summer of 1944, “had any doubt that Germany had definitely lost the war. This was settled on the Soviet-German front in 1943 and the beginning of 1944. The question now was how soon and with what political and military results the war would end.”

Lend-Lease Tonnage to the Soviet Union, 1941–45

PREPARATIONS TO DESTROY ARMY GROUP CENTER

The man tasked with designing the Soviet offensive to smash Army Group Center was General Aleksei Antonov, the forty-seven-year-old son and grandson of Imperial Russian Army officers. Shortly after assuming his new post as first deputy chief of the general staff in May 1943, Antonov, with the support of marshals Aleksandr Vasilevskiy and Zhukov, tried to persuade Stalin to stand on the strategic defensive in the summer of 1943, something Stalin vigorously resisted. Antonov argued that the Wehrmacht, if allowed, would inevitably attack the extensive Soviet defenses inside the Kursk salient and waste its best armored forces in doing so.

At first Stalin refused, demanding another Soviet offensive—the very action the Wehrmacht was still capable of defeating, as it demonstrated after the Stalingrad disaster in the Kharkov counteroffensive.80 To his generals’ surprise, however, Stalin finally relented and approved Antonov’s plan. The resulting success at Kursk confirmed the wisdom of Antonov’s plan and earned him Stalin’s trust. Unlike Hitler, who increasingly disregarded sound military advice, Stalin heeded the counsel of men who in his eyes had proven themselves in the crucible of war.

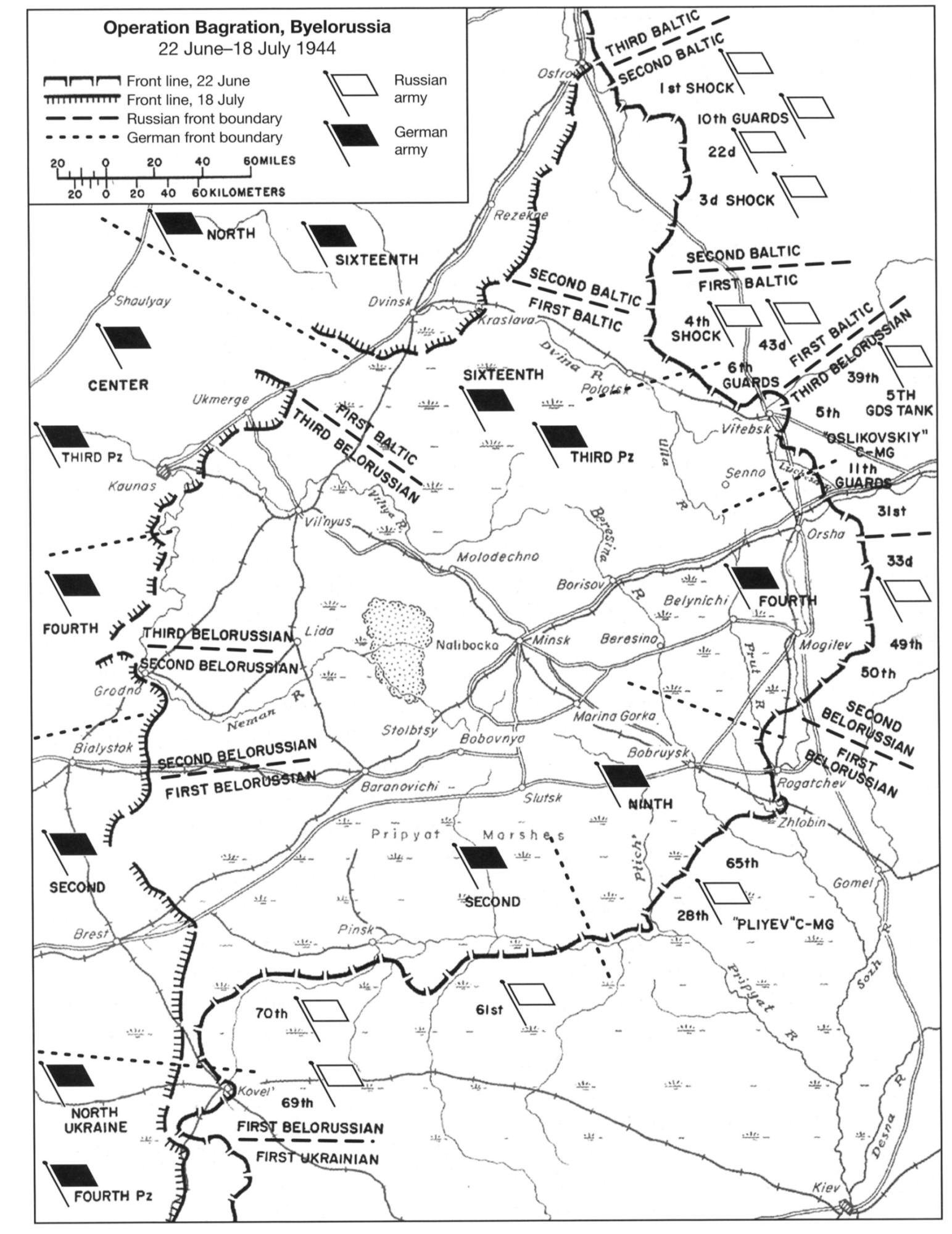

In its final form, Antonov’s design for the offensive resembled the operational constructs for deep battle and successive operations envisioned during the interwar years. The Soviet operation was planned in three phases, and the attacking Soviet forces were organized in two echelons. The operational objective in the first and second phases was to entrap Army Group Center and destroy what remained of it with air and ground attacks by four Soviet fronts moving west along three axes. The concept entailed the convergence of the four fronts along nearly parallel axes north, south, and west of Minsk. The resulting encirclement of German forces was to be accomplished by the simultaneous defeat of Army Group Center’s flank forces, around Vitebsk and Bobruisk, as well as at Mogilev. The outcome, Antonov believed, would open the road to Minsk so that Soviet forces to its west could cut the German escape route.

In the opening phase, the first echelon was tasked with penetrating and destroying the defending German forces on the flanks in the north around Vitebsk and in the south around Bobruisk. Breakthrough artillery divisions employing thousands of large caliber guns were massed together with air armies to pin down and wipe out German fighting strength in Army Group Center’s forward defenses. These tasks were critical; Soviet military leaders knew from experience that if they did not annihilate the troops in the forward defensive positions strewn among Belorussia’s bogs and thick woods, the Germans would retire, regroup, and counterattack with the support of rapid reinforcements.

In the second phase, the Belorussian bulge in the German front was to be cut off and encircled through concentric exploitation attacks launched by the tank and mechanized forces of the first and second Belorussian fronts. Soviet commanders were ordered to strike deep and ignore their flanks with the goal of uniting Soviet forces west of Minsk, deep in Army Group Center’s rear areas. All Soviet tank formations were equipped with brush and logs to carry the tanks over the soft ground of Belorussia’s marshes. Combat engineers, as well as infantry, were attached to all tank and self-propelled gun units to remove obstacles and accelerate river crossings.

In the third phase, the attacking Soviet fronts were ordered to pursue the remnants of Army Group Center as they retreated west. The First Belorussian Front under General Konstantin Rokossovskiy would begin its attack along the Pripyat marshes toward Kovel when the bulk of Army Group Center’s forces were encircled around Minsk and attacking Soviet forces reached the vicinity of Baranovici.

The strategic objective was obviously Warsaw, not the Baltic coast. Had Soviet forces pressed northwest toward the Baltic, the resulting effect would have been much greater—similar to the impact of the German thrust in 1940 from Sedan to the French coast. However, in the summer of 1944 recapturing Warsaw involved political interests that trumped military practicality.

Marshal Zhukov and Marshal Vasilevskiy were selected by Stalin to coordinate the operations of the fronts during the offensive, a technique used repeatedly during the war. Zhukov coordinated the First Belorussian Front, the Second Belorussian Front, and later, the First Ukrainian Front. Vasilevskiy coordinated the offensives of the First Baltic Front and Third Belorussian Front. In practice, “coordination” meant that the two marshals shared aircraft of the four air armies assigned to each of their fronts.

Originally scheduled to begin on 18 June 1944, Operation Bagration was delayed until 22 June, 3 years to the day after the Wehrmacht had invaded Russia. The delay was deemed necessary to ensure sufficient Soviet forces were assembled to retake Belorussia: 2.5 million men (including 1,254,300 Soviet troops in the attacking echelons), 45,000 artillery systems (including 2,306 Katyusha rocket artillery), 6,300 tanks and assault guns, and 8,000 fighters and fighter bombers. This massive Soviet force would be hurled against the German armies that were stretched thin along a 660-mile front between Vitebsk and Bobruisk. The operation’s name, Bagration, was chosen to honor the tsarist general who had participated in the campaign of 1812–13 to drive Napoleon out of Russia.

As the buildup for the offensive began, Antonov developed a deception plan (maskirovka) intended to convince the OKW that the Soviet fronts would make their main attack in the Ukraine and the Baltic littoral, not in Belorussia. Maskirovka entailed the collective employment of deception measures in all aspects of Soviet-Russian military operations, including actions to confuse and mislead opponents and camouflage intentions. Radios were sealed to prevent their use as part of a total blackout, and false troop concentrations were organized in both sectors. All six Soviet tank armies dedicated to Operation Bagration were held in the Ukraine until they regrouped at the last moment and occupied new assembly areas farther north, ensuring two-thirds of the Wehrmacht’s armored formations remained in the Ukraine when the hammer blow fell on Army Group Center.

Antonov’s deception appeared to work, but not because the German commanders in the front lines were fooled. Intelligence officers serving under Colonel General Georg-Hans Reinhart, commander of the Third Panzer Army, reported unmistakable signs of a Soviet buildup and impending attack in early June. Colonel General Hans Jordan, commander of Ninth Army, was so alarmed by the buildup along his front that he personally informed Field Marshal Ernst Busch, the commander of Army Group Center. Busch did not listen because Hitler would not listen—a pattern that would work to Soviet strategic advantage throughout Operation Bagration and for the rest of the war.

OPERATION BAGRATION BEGINS

On 19 June, German intelligence intercepted Soviet radio transmissions instructing 143,000 Soviet partisans to attack Army Group Center’s rear areas. German and local (Lithuanian, Belorussian, and Ukrainian) auxiliary security forces deployed early and were able to shut down or neutralize most of the insurgent attacks, but they signaled an impending Soviet offensive no one in Army Group Center could ignore.

Unfortunately for the soldiers under his command, Field Marshal Busch, Hitler’s choice to command Army Group Center in 1944, subscribed to Hitler’s view that the Soviet summer offensive would be launched against Field Marshal Walter Model’s Army Group North in the Ukraine from the area south of Kovel. Busch incorrectly perceived Belorussia as a wooded, swampy morass where rapid movement was difficult for tanks. Events would prove that Busch was totally wrong.

Busch’s war record as a combat commander did not recommend him for a critical field command such as Army Group Center. Colonel General Georg von Kuechler, the commander of Army Group North, actually requested Hitler’s authorization to relieve Busch of his command for gross incompetence in 1942. Hitler refused. Busch owed his field marshal’s baton to his National Socialist attitudes. He was a “yes man” in the worst sense of the term, a “Marionette in [a] Marshal’s uniform.” Busch transformed Army Group Center’s headquarters into a mindless instrument for the transmission of Hitler’s increasingly ludicrous orders.

Busch’s readiness to embrace Hitler’s directives without question placed Army Group Center in a perilous position. Busch subscribed to Hitler’s notion that key towns and cities could be converted to fortified places, a strongpoint defense concept that failed repeatedly during the previous winter. In Army Group Center, the designated fortified places were Vitebsk, Orsha, Mogilev, and Bobruisk—sites that Busch pledged to Hitler would be defended to the last man.

Between the Third Panzer Army, Fourth Army, and Ninth Army, Army Group Center fielded the equivalent of 29 understrength divisions (with 5 more understrength divisions in reserve), or 336,573 troops together with 118 tanks and 337 assault guns in 4 understrength Panzer and Panzergrenadier divisions. The low proportion of tanks to assault guns was based on Hitler’s insistence that Army Group Center would fight static defensive battles in Belorussia’s forested and swampy terrain.

German defensive positions were nevertheless well prepared with secondary defense lines. Millions of mines were placed in dense minefields stretching across Army Group Center’s front and in depth. Behind the front were an additional 300,000 men, but these were primarily administrative, supply, training, transport, and police units, not combat troops.

However, on the day the Soviet offensive began, the 3 German armies mustered only 166,673 men. Since Hitler believed no imminent Soviet offensive was possible against Army Group Center, large numbers of German soldiers were allowed to go on leave. Opposing those German soldiers in the defensive line were 1,254,300 Soviet soldiers armed with 2,715 tanks and 1,355 assault guns.

Alarmed by the Soviet buildup to their front, all of Busch’s army commanders expressed the view in early May that the fortified places concept was self-defeating and that Army Group Center should withdraw farther west, shorten the front, and occupy defensive positions behind the Beresina River. Given the overwhelming Soviet superiority immediately in front of Army Group Center’s three armies—an advantage of 23:1 in tanks, 4:1 in assault guns, 9:1 in infantry, 10:1 in artillery, and 58:1 in fighter aircraft—the withdrawal to a shorter, more defensible line in late May or early June made infinite sense.

Still, Hitler refused to consider any withdrawal, resulting in the following deployments on the eve of the Soviet offensive. On the northern shoulder of Army Group Center, General Reinhart commanded the Third Panzer Army—an army without Panzer divisions or tanks, but instead having only 60 to 80 assault guns and tank destroyers, plus 60,000 horses for transport and resupply. In addition to being exposed on three sides at the northern tip of the Belorussian bulge, Reinhart’s force was weak in firepower and mobility, with just 7 understrength infantry and 2 Luftwaffe field divisions (air force ground combat formations) to defend 130 miles of Army Group Center’s front.

In its center, Fourth Army consisted of roughly 362 medium artillery systems, 205 heavy guns, 246 assault guns, 40 tanks, and 116 self-propelled 88-millimeter guns deployed primarily in an anti-tank defense role. Fourth Army’s field strength was equivalent to a 1938 German army corps (50,000 men).

With almost 80,000 men, including 43,555 infantrymen, Ninth Army on the southern shoulder was stronger. Ninth Army also had 76 assault guns and 551 artillery systems of all calibers. Seven thousand additional troops were placed in corps and army reserve. On the southernmost flank of the Belorussian bulge facing the Soviets’ Northern Ukrainian Front, Second Army had 20,000 men, or 6 division equivalents including 2 Hungarian cavalry divisions.

Army Group Center maintained relatively small reserves. The heaviest concentration of armor, one battalion of 29 Tiger I tanks, was committed to the defense of Orsha in Fourth Army’s sector. Otherwise, Army Group Center’s tank strength consisted of older Mark IV Panzers fitted with long-barreled 75-millimeter guns weighing in at 20 to 22 tons. They were good tanks but were much lighter than the 36-ton Soviet T-34s. To maximize their effectiveness, the Mark IVs had to maneuver to strike the T-34s from the flank or rear. However, given the reduced availability of fuel, the ability of German tanks to maneuver was limited.

Operation Bagration in Two Phases

Colonel General Ritter Robert von Greim’s Sixth Air Fleet headquarters was in Minsk. The airpower at his disposal to support Army Group Center consisted of 839 aircraft, of which only 40 were Me-109G/K fighters. Ground attack units included 106 Ju-87 Stuka tank busters and Fw-190 fighter bombers.106 Because the Sixth Air Fleet lacked the fuel reserves to keep most of its aircraft flying for more than a few hours, the impact of German airpower on the battle would be minimal.

On 22 June, Soviet forces conducted probing attacks all along the front. The First Baltic Front and Third Belorussian Front launched the heaviest attacks at General Reinhardt’s Third Panzer Army on either side of Vitebsk. Field Marshal Busch flew back from Hitler’s residence in Berchtesgaden on the Austro-Bavarian border and began organizing reinforcements. During the night of 22–23 June, the Soviet air force’s strategic bomber force followed up the probing attacks of 22 June with one thousand sorties using Il-4 and Tu-2 bombers against major German troop concentrations and artillery positions.

At 5 a.m. on 23 June, 40,000 Soviet artillery systems announced the main attack. Most of the artillery strikes started with intense shelling designed to obliterate German formations in the forward defensive lines before they could retire to secondary positions. In some sectors, the initial artillery attacks were followed by rolling barrages; in other sectors where the German defenses were particularly dense, double rolling barrages were used to simultaneously attack German defenses in depth. Three rocket artillery divisions added their firepower to the assault, saturating German infantry, armor, and artillery in their defensive positions. German accounts of these artillery strikes describe them as being of an intensity and destructiveness never before seen on the eastern front.

As the artillery fire slackened, 14 Soviet armies attacked along a 300-mile front concentrating 27 divisions in the first echelon at 6 critical points to break through German defenses. In contrast to previous offensives, the Soviets deliberately concentrated their firepower (204 guns per kilometer) with daring and imagination. At each point of attack, on average at least 750 Soviet infantrymen attacked 80 German infantrymen—assuming any of the defending German infantry survived the initial Soviet artillery and air strikes.

Almost immediately, Third Panzer Army needed help. Its infantry trench strength was at most 11,000, far too weak to halt the 100,000 Soviet infantry and tank forces penetrating north and south of Vitebsk. Quickly discerning the outlines of the Soviet plan of attack, Reinhart urged immediate withdrawal to avoid encirclement. Busch adamantly refused, saying, “If we start withdrawing now we will all end up in the drink!”

Busch eventually changed his mind. Early in the afternoon of 23 June, Busch informed OKW that Third Panzer Army’s LIII Corps had to be allowed to retreat or be overrun. General Adolf Heusinger, OKW’s chief of operations, agreed and urged Hitler to allow Third Panzer Army to retreat to the Dnieper River. Because this would mean abandoning Vitebsk, Hitler’s designated “defended place,” he denied the request.

On 24 June, Reinhardt organized a counterattack with 3 understrength divisions, roughly 15,000 men who had been sent to Third Panzer Army as reinforcements. Their mission was to break through to Vitebsk, which was now completely surrounded. They came within 6 kilometers of the city center, but their counterattack was too feeble. Even Field Marshal Busch realized it was time to abandon Vitebsk.

Colonel General Kurt Zeitzler, chief of the German army general staff, felt compelled to intervene on behalf of Busch. Zeitzler flew to Berchtesgaden to meet personally with Hitler on 24 June. After speaking with Reinhart on the phone at 3:40 p.m., Zeitzler presented the situation to Hitler, repeating Reinhart’s words that “the last possible minute had arrived” and asking for permission to withdraw the remaining German forces from Vitebsk before the ring closed. Hitler authorized the withdrawal of Reinhart’s already encircled LIII Corps but insisted that Vitebsk must be held by the 206th Infantry Division, the understrength division reinforced with the shattered remains of flank elements.

Inside Vitebsk itself, Soviet and German troops were already fighting hand to hand for the possession of buildings serving as German strongpoints, but what the Soviets wanted most was the bridge over the western Dvina River. Marshal Vasilevskiy was well aware of the confusion in OKW, but he feared that if German forces retreated over the Dvina to establish a new defense line, the First Baltic Front’s offensive on the northern flank could come to a dangerous halt. Urgent orders were issued for a river crossing.

At noon on 24 June, Marshal Vasilevskiy was relieved to learn that Soviet forces had finally crossed the Dvina during the night on improvised rafts, plank, and boats. By evening pontoons arrived, and Soviet tanks and artillery began moving behind the German defenses. As darkness covered the battlefield, Soviet tanks and infantry were closing in on Third Panzer Army headquarters.

Soviet forces had opened a breach in Third Panzer Army’s sector that was roughly eighteen miles wide, allowing Soviet tanks and mechanized forces to stream by on the left and right of Vitebsk through a twenty-mile break in Third Panzer Army’s defense line. While Hitler dithered on 24 June, Third Panzer Army’s divisions, essentially dismounted infantry forces with assault guns, were pulverized by Soviet tank forces supported by hundreds of heavy guns in the breakthrough divisions. Hitler’s refusal to allow his commanders to exercise their own best judgment and maneuver accordingly was turning a potentially life-saving retreat into a rout.

On 25 June, Busch transmitted another of Hitler’s “fight to the last man” orders to the 206th Infantry Division in Vitebsk. Oblivious to the conditions on the battlefield, Hitler actually ordered Reinhart to parachute a general staff officer into Vitebsk to personally convey to General of Infantry Friedrich Gollwitzer, the LIII Corps commander, that German forces still in Vitebsk were to fight and hold out to the last man. Fortunately, the order was ignored. Eventually, 8,000 of Vitebsk’s defenders broke out and rejoined Third Panzer Army in occupying defensive positions farther west, but 27,000 men perished needlessly defending Vitebsk when it was finally overrun on 27 June. General Reinhardt subsequently recorded, “Constantly acting against my better judgment is more than I can do.” His force would live on to fight in the Baltic littoral until war’s end.

On 23 June, Soviet attacks against Fourth Army initially were less successful than those against Third Panzer Army. The preliminary Soviet artillery attack by the 5th Breakthrough Artillery Corps fell on open ground, missing the German anti-tank gun positions and leaving German defenses intact. Given that the main Moscow-Minsk highway from Smolensk to Orsha was crucial to the Soviets’ deep operation, this was a troubling development.

The German defenders in Fourth Army did what they had previously done. They observed the Soviet preparations and methodically plotted the Soviet artillery deployment. Even when additional Soviet tanks and aircraft were hurled against the German defenders, Fourth Army picked up elements from Third Panzer Army that had been cut off and incorporated them into the fight. Miraculously, Fourth Army held on until the main roads from Orsha to Borisov were cut. Then, on 26 June, Soviet forces crossed the Dnieper north of Mogilev, putting Fourth Army at risk of encirclement.

General Kurt von Tippelskirch, temporarily commanding Fourth Army after Busch relieved General Hans Jordan, ignored another of Hitler’s “stand fast” orders and saved what was left of his army pulling it away from the Dnieper. Busch was furious, screaming at von Tippelskirch over the phone, “Your behavior is in contravention with the Führer’s orders.” Tippelskirch was unimpressed and acted in accordance with his best judgment.

Ninth Army was attacked on 24 June. Woefully understrength individual German infantry battalions defended their positions against the simultaneous attacks of two Soviet divisions. General Rokossovskiy achieved almost complete surprise with a massive concentration of tanks where the Germans least expected it: in the theoretically impassable swamp lands on the southern edge of the Pripyat marshes. Within twenty-four hours, Ninth Army’s forward defenses were smashed and its main forces were in danger of being encircled by a pincer movement on Bobruisk from the east and the south.

This time, Hitler responded differently. He directed the transfer of two divisions from Army Group North to support Army Group Center, and Busch authorized the commitment of Ninth Army’s reserve, the 20th Panzer Division, an understrength unit with only one regiment of seventy-one Panzer IVs. After a series of confusing orders from Busch and Hitler, the 20th Panzer met advancing Soviet forces near Slobodka, south of Bobruisk. The 20th Panzer destroyed sixty Soviet tanks but lost half its strength in the battle, eventually joining German forces inside Bobruisk.

Meanwhile, Orsha, another of Hitler’s fortified places, fell on 27 June, trapping 40,000 German troops 14 miles east of Bobruisk. This pocket was in close proximity to the massive concentration of Soviet breakthrough artillery formations, making German breakout attempts impossible. At least 10,000 German troops were killed and 6,000 were taken prisoner; the surviving troops fled into Bobruisk, where they were once again encircled.

On 27 June Hitler granted the German troops inside Bobruisk permission for a breakout but insisted, as he had in Vitebsk and Mogilev, that a division remain in Bobruisk to defend the “fortified place” to the last man. The Ninth Army chief of staff recorded that Hitler’s orders were tantamount to operational insanity.

The breakout from Bobruisk began on 28 June at 11 p.m. With the 20 to 25 surviving tanks from 20th Panzer Division in the lead, about 15,000 German troops managed to break out and escape destruction when Bobruisk fell into Soviet hands on 29 June. In less than 7 days of fighting, the First Belorussian Front under Rokossovskiy had captured or destroyed 366 armored vehicles and 2,664 artillery systems and killed 50,000 German troops and captured a further 20,000. German forces were now being driven west into a new death trap forming in and around Minsk. On the Soviet side, events were unfolding according to plan.

SALVAGING THE RUINS OF AN ARMY

On 28 June, Hitler finally relieved Busch of his command, replacing him with Field Marshal Model, the commander Hitler had chosen from the beginning to meet the summer Soviet offensive. At this point in the battle, there was not much Model could do to rescue Army Group Center. Earlier in the year, Hitler moved the bulk of German tank strength and equipment into Army Group North Ukraine, where he expected the massive Soviet summer offensive to occur. Hitler’s decision had left only a few sparse tank reserves available to Model, who could do little to forestall the fall of Minsk, already largely encircled.

The approaches to Minsk were held by perhaps 18,000 troops from various units: police, supply, and infantry formations reinforced with 125 tanks of the German 5th Panzer Division. Northwest of the city, the 5th Panzer destroyed 295 Soviet tanks. One hundred twenty-eight of the destroyed Soviet tanks were credited to the 20 Tiger tanks in 5th Panzer, but all of these successful German actions could do little more than buy time for a sensible withdrawal from Minsk, an action Hitler once again forbade. Meanwhile, the Third and First Belorussian fronts simply avoided the 5th Panzer by swinging north and south to envelop the city as originally planned. Once Minsk was encircled, Soviet airpower was skillfully concentrated to destroy tens of thousands of trapped German troops. Without food, ammunition, or motorized transport, very few German soldiers survived to fight their way west through Soviet lines.

At the führer’s headquarters, General Heusinger mobilized everything at his disposal to reinforce Army Group Center. While a few German formations from Army Group North moved south to assist Army Group Center, on 2 July Heusinger summoned the 6th Panzer Division from Germany, the 18th SS Panzer Grenadier Division from Hungary, the 367th Infantry Division from Army Group North Ukraine; later, the 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf and even formations from as far away as Norway were ordered to the eastern front. But these additional formations were still too few in number to stop the 116 Soviet rifle divisions, 6 cavalry divisions, 42 tank brigades, and 16 motorized rifle brigades that were streaming into eastern Poland.

On 3 July, the German position deteriorated further. The Germans lost Minsk, the capital of Belorussia, and by 8 July, the 5th Panzer Division was down to 18 tanks, the size of a reinforced battalion. All of the Tiger tanks were destroyed or abandoned.124 Soviet tank forces had advanced 120 miles in 10 days, tearing a 250-mile-wide gap in Army Group Center, which was shattered and ceased to exist.

Having reached the third phase of the operation, Stavka now assigned new objectives to the front commanders: First Baltic Front was aimed at Kaunus and Third Belorussian Front at the Molchad and Niemen River lines, and from there to Bialystok and the western Bug River. Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital, was encircled and fell into Soviet hands on 13 July. Shortly after dawn on 17 July, 170,000 artillery shells fell on German forces attempting to defend a new defense line east of Lublin, Poland. Nine Soviet infantry armies crushed the German defenders, and Lublin fell on 23 July. The Soviet pursuit, moving at a rate of 15 miles a day, now turned northwest toward the Vistula River and Warsaw.

Knowing eastern Poland offered little in the way of defensive terrain, Field Marshal Model ordered the 3rd SS Totenkopf division to hold a line fifty miles east of Warsaw. This new defense line meant the Soviet armed forces would inevitably end up less than four hundred miles from Berlin. The Waffen SS battle groups held long enough for the German Second Army to escape encirclement before beginning its own withdrawal west on 28 July while executing a series of punishing counterattacks against advancing Soviet tank forces.

For his rapid advance into central Poland, Stalin promoted Rokossovskiy from general to marshal and ordered him on 2 August to take Warsaw with the support of two Soviet fronts moving up on his left from the Ukraine. It was not to be. On 11 August, Totenkopf finally crossed the Vistula River northeast of Warsaw and set up new defensive positions. For the next seven days, Totenkopf, together with SS Panzergrenadier Division Wiking (Viking), turned back a series of Soviet breakthrough attempts to reach and capture Warsaw.

At the end of August, German troops reported seeing Soviet troops on the east side of the Vistula building anti-tank gun fronts, a defensive tactic that placed low-profile, high-velocity, flat-trajectory guns in depth. The message was unambiguous: Operation Bagration was finally over. Stalemate ensued.

Having advanced three hundred miles in five weeks, Soviet forces were overextended and exhausted. But the Soviets were now far closer to Berlin than U.S. and British forces were, although the Soviets would not renew offensive operations in western Poland until January 1945.

The destruction of Army Group Center was a stupendous military achievement, but encirclement and pursuit of the German units assigned to Army Group Center were no cakewalk for Soviet forces. Despite overwhelming superiority in every meaningful category of military power, Soviet casualties between 23 June and the end of July were much higher than was reported at the time: 440,879 soldiers, including 97,232 (roughly 30 percent of the attacking ground force) killed.

CONCLUSION

Operation Bagration was the most strategically important combat operation of World War II for the simple reason that it epitomized the Soviet revolution in warfare. It represented the collision of two military reforms; the Germans dramatically increased their tactical fighting power at the point of impact, while the Soviets expanded their power to dominate the whole battlespace on the operational and strategic levels. Events in the summer of 1944 showed that the Soviet transformation was the more effective of the two, as Stavka demonstrated its nearly full-spectrum dominance in central and eastern Europe.

Though the war would continue for another ten months, the spectacular advance of Soviet military power over the wreckage of Army Group Center into the heart of Europe ensured the destruction of the Third Reich and Stalin’s conquest of central and eastern Europe. The Soviet command structure, organization for combat, and supporting doctrine for the application of military power in the form of strike—artillery, rockets, and airpower—with operationally agile maneuver forces created a margin of victory that changed the course of European and world history.

The partial transformation of the Wehrmacht that provided Germany with its margin of victory in 1939 and 1940 turned out to be insufficient for an extended conflict with Stalin’s war mobilization state. Without the mobile armored firepower and the aircraft it needed to dominate the enormity of the Russian theater of war, the Wehrmacht’s superior tactics could not produce the operational victories with strategic impact that Germany needed in 1941 and 1942. Russia swallowed vast numbers of dismounted German infantry, and without mobility and firepower, the World War I–styled infantry divisions were doomed to be overrun and destroyed in warfare that rewarded mobility, protection, and firepower.

As the war with the Soviet Union dragged on, Germany lost the profound edge in military capability it possessed at the outset. When the war entered its final twelve months, nearly 85 percent of the German army’s supply and transport was horse-drawn, in part because there was so little fuel for wheeled vehicles and because mechanization had proceeded too slowly.

The Wehrmacht was defeated in World War II because Hitler and his generals disregarded one of the most important principles of international conduct articulated about 110 years ago by Clausewitz: “No one starts a war—or rather, no one in his senses ought to do so—without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by that war and how he intends to conduct it. The former is its political purpose; the latter its operational objective.” From July 1943 onward, the Wehrmacht in Russia lacked a definitive operational purpose and an attainable strategic objective. By January 1944, the Wehrmacht’s margin of victory was effectively lost. German soldiers and the forces fighting with them from Finland, Hungary, Croatia, Romania, and Spain simply defended their assigned sectors to the best of their ability, and often to the death.

The Soviet Union won World War II in eastern Europe because the Communist Party of the Soviet Union organized its forces to achieve absolute unity of command. The appointment of senior commanders at the army and front levels with total, uncontested authority to employ and integrate all of the forces under their commands (army, navy, and air force) eliminated the interservice fights for prominence and control of resources that were common inside the German, British, and American forces. Thanks to this unique condition of unity of effort throughout the theater of war, the Soviet high command could commit troops and resources when and where they were needed quickly and efficiently on the strategic and operational levels of war.

When the opportunity presented itself, a Soviet marshal could do in minutes what took General Dwight D. Eisenhower months of negotiation with U.S. and British air force commanders to do: unleash 700 long-range bombers to attack and destroy 50,000 German troops encircled by Soviet tank forces. The Soviet capability to concentrate and move forces in time and space on a scale that achieved a dramatic strategic impact did not end with Operation Bagration. The subsequent Soviet campaign in Manchuria during August 1945 followed the pattern of integrated strike and maneuver operations in the Belorussian offensive, eventually providing the inspiration for Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov’s Reconnaissance Strike Complex. Ogarkov extended the idea of integrating strike and maneuver forces to incorporate the growing arsenal of intelligence, surveillance, and strike assets. It is no exaggeration to suggest that the successful conduct of Operation Bagration was a watershed event in Soviet military thinking and force development.

In retrospect, no two armed forces ever fought harder for worse causes: the one for National Socialism, and the other for national survival as well as communism. For most Germans, the suffering ended with the destruction of the Nazi state in 1945, but suffering inside the Soviet Union and in the nations Stalin conquered in the last year of World War II continued until 1989.

In 2001, the Narodnii Kommisariat Vnutreniikh Del’ (NKVD, or the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) archives were closed when the public reacted with horror to the news that Soviet losses were certainly twice what the Communist Party admitted to during the war with Germany. In 2009, Russian authorities released revised figures claiming nine million Soviet soldiers and twenty-seven million to twenty-eight million civilians were killed in the conflict, but the Russians are always “economical” with the truth. The world will probably never know the true figures.

Germany rebounded dramatically. Today, Germany is once again Europe’s leading political and economic power, but Stalin’s legacy haunts post-Soviet Russia. Were a visitor from another planet to see contemporary Moscow after seeing contemporary Berlin, he or she would conclude that Berlin, not Moscow, had won planet Earth’s last great war.