The First Restoration

When the allied armies occupied Paris, they issued a

declaration under the name of the Austrian commander-in-chief, Schwartzenburg,

refusing to deal with Napoleon or any member of his family and inviting the

Senate to form a provisional government. For the first time in public at any

rate, the allies proclaimed the overthrow of the Empire as one of their aims.

This made a restoration of the Bourbons inevitable. There had to be a new

constitution. This was the work of the Senate which contributed five of its

number to the provisional government and twenty members to a constitutional

commission. That is, the body which took responsibility for deposing Napoleon

on 2 April was composed of men from the old revolutionary legislatures, the

dignitaries of the Empire, imperial officials, officers and the like. The

conceptions of government of all these men reflected their backgrounds as

revolutionary and Napoleonic politicians and officials. There would be a

bicameral legislature responsible for consenting to taxes, an independent

judiciary, equality of opportunity, an amnesty for all political opinions,

freedom of religion and the press, fiscal and legal equality, irrevocable

guarantees for owners of biens nationaux, and recognition of both the Old

Regime and imperial nobilities. Although this was changed later, it was even

said that Louis XVIII was `called’ to the throne by `the French people’, in

other words, the nation, not the king, was sovereign. Strangely, many members

of the Senate who drafted this document were from the annexed territories that

were eventually split off from France itself. In a sense, therefore, the

Charter was a European document, imposed upon the French without so much as a

referendum to endorse it. All the other constitutions, except that of 1791, had

been placed before the electorate. It should not be surprising that the

`Charter’ resembled the Constitution of 1791. The self-appointed constitutional

committee liter- ally had a copy available to consult.

If the `men of 1789′ were to triumph, it was essential to

get Louis XVI’s brothers to accept the Charter. In the event, it was forced on

them. When the comte d’Artois arrived in Paris in early April in the uniform of

the National Guard no less, the Senate was extremely reluctant to recognize his

title of lieutenant-general until he accepted the Charter. Tsar Alexander also

insisted that he recognize it. Thus the emergence of a parliamentary regime in

France depended upon a completely unelected body and upon the most despotic of

the European monarchs. With nowhere to turn, Artois conceded. As long ago as

1805, his brother the Pretender had interred the Declaration of Verona which

had promised an integral restoration of the Old Regime. Instead, the Pretender

accepted the existing judicial, military and administrative structure but said

nothing about a legislature with powers over taxation. Another declaration

issued from his English residence at Hartwell on 1 February 1813 reiterated

these points and expressed the hope that the issue of biens nationaux could be

settled by `transactions’ among the present and former owners. Privately, he

disliked the notion of the state paying Protestant ministers.

In the circumstances of 1814 he too would have to bend and,

recognizing reality with none of Artois’s bad grace, he waited until the eve of

his entry to Paris to publish the Declaration of Saint Ouen on 3 May which

accepted the principles of the Senate’s project but not the actual document. A

new commission set to work on a new charter which differed from the old only in

that the Senate was replaced with a Chamber of Peers nominated by the king, the

`senatoreries’ were abolished, and the most restricted franchise of the entire

period was adopted for the Chamber of Deputies. This put electoral power overwhelmingly

in the hands of big landowners. Finally, the preamble to the Charter did not

recognize national sovereignty; instead the Charter was said to be `granted’ by

the king. Thus were planted the seeds of the revolution of 1830.

The fact that the Restoration was effected the way it was

ensured that it would not be counterrevolutionary. None of the elements of

opposition to the Empire the clergy, the malcontents in the army, the

intelligentsia or the royalists of the Chevaliers de la Foi – played- a crucial

role. Nor had the out-and-out reactionaries. In 1790, Artois and the emigres

had planned to effect the counterrevolution by a combination of a military

conspiracy and popular insurrection. Yet in 1814, the officers had remained

loyal almost to the last and many of the troops were Bonapartist. In fact there

had been no great royalist upsurge. Even the royalists of Bordeaux were

probably a minority. At its most optimistic, the little royalist Bordelais army

never numbered more than 800 in a city of 70,000. Elsewhere, violent royalism

was rare. The Chevaliers de la Foi tried to seize Rodez but the leaders called

it off when only 200 `knights’ showed up. There was a royalist riot at

Marseille on 14 April in which Provencal-speaking crowds vainly attacked the prefecture.

This showed that popular royalism still existed but such disturbances were

almost unique. Even the old Vendee militaire and the chouans north of the A

Loire had not risen, an indication of just how effective the imperial

government’s policy of disarming the west had been. Instead, the young men had

responded by trying to avoid conscription, and by the spring there were signs

of a general breakdown of law and order as brigand bands roamed the

countryside. But this was only a pale shadow of the great days of 1793.

There were even pro-Bonapartist demonstrations. Peasants in

Lorraine, goaded beyond endurance by requisition or outright pillage, formed

partisan units. One of them was actually led by a parish priest whose men

showed considerable skill in guerrilla attacks. There are numerous examples of

country people killing allied stragglers or observation troops or picking up

muskets from allied dead on the battlefield and turning them over to imperial

soldiers or coming forward to help troops move heavy cannon through the muddy

roads of Champagne. In mid-April, soldiers stationed in Clermont-Ferrand

countered the prefect’s reading of the de- position decree with cries of `Vive

l’Empereur!’, while a crowd of cavalrymen led by junior officers broke down the

door of the cathedral to harass a priest who had unfurled the white flag of the

Bourbons. In the countryside of Auvergne, there were rumours that a restoration

presaged the re-imposition of the tithe and feudal dues, while later that

summer in a few communes peasants paraded an effigy of the king on an ass. In

Strasbourg, soldiers almost rebelled when they were told to wear the royalist

white cockade. Almost everywhere there was a general refusal to pay taxes, and

in some places there were anti-rscal rebellions. In the Haute-Garonne, Gironde,

Vendee, Seine-Inferieure, Pas-de-Calais and at Marseille, A A Rennes, Cahors,

Chalon-sur-Saone and Limoges, officials of the droits reunis and the octroi

were attacked and their registers burned. Royalist A agents and a proclamation

of the Prince de Conde had led people to believe A that those taxes would be

abolished or much reduced. In some regions like Anjou, people acted on this

propaganda, reasoning that since the war was over no taxes at all were

necessary ± a remarkable example of the survival of medieval notions of fiscality.

When Louis XVIII maintained the droits reunis, disappointment was sharp.

Given time, the restored Bourbons might have been able to

assuage these fears, but from the top down experience soon showed that

reconciling the servants and loyalists of the imperial and royalist regimes

would be far from easy. As major instruments in overthrowing Napoleon, the

senators did exceptionally well. Only 37 of the French senators were excluded

from the 155-member Chamber of Peers, 12 because they were conventionnels,

while 84 were included, each with a magnificent pension of 36,000 francs. To

the end, they had known how to look after themselves. The continuity of

personnel among the upper courts was also great but other institutions suffered

more. Since it was so closely identified with the Emperor, it is not surprising

that 40 per cent of the members of the Council of State were eliminated. There

was no thoroughgoing purge of the prefectoral corps but 28 of 87 were fired

outright because they had been revolutionaries or imperialist zealots, while of

the 36 new appointments which the first Restoration made, one third were former

emigres. The number of nobles in the corps as a whole nearly doubled – a significant

indication of whom the regime thought its friends were. Much of this was to be

expected and the purges were not very great in comparison to those of the

previous twenty-five years, but the voluble courtiers around the comte d’Artois

let it be known that this was only the beginning of a vast settling of

accounts. Intelligent and indolent, Louis XVIII could not muzzle his dim and

impetuous brother.

A careless historiography usually blames the Bourbons

themselves and the utterances of careless ministers for what happened next.

This is far too simple. Whatever gaffes various ministers committed, public

opinion did not turn against the First Restoration overnight. Instead, opinion

remained totally loyal to the Emperor.

In the constitutional scheme of things, the common people

counted for nothing so nothing was done to wean them from the shock of

Napoleon’s defeat. Thus the Emperor retained much of his popularity well after

his abdication. The old Napoleonic bric-a-brac – playing cards, medallions, A

statuettes, broadsheets, dinner plates, and so on – continued to circulate with

the addition of mawkish engravings of the Emperor coming the King of Rome to

the care of the National Guard who supposedly represented the French people.

Enterprising printers put out other drawings depicting a sleeping eagle with

the caption, `He will return!’ Prisoners of war returned with a grudge. Those

who returned from the ghastly hulks of English prison ships were looking for

revenge. Prisoners from Germany, whom the allies had overrun, knew they had not

been defeated. Soldiers like these would welcome a second chance.

Indeed, there were rumours from the beginning of the

Restoration that he already had returned or had escaped to raise an army in

Turkey. The docks in the lower courts were jammed with unfortunate individuals

being prosecuted for having shouted `Vive l’Empereur!’ within earshot of a

gendarme. During the Second Restoration especially, there were many who

predicted that his third coming would be a prelude to the end of days or that

he returned secretly and spoke only to those who really believed or to innocent

children.

Many simply refused to believe the Emperor had gone. Many

believed that somehow Napoleon had been betrayed. Even defeat did not convince

soldiers from Spain who marched through the streets of Grenoble shouting `Vive

l’Empereur! Vive Le Roi de Rome!’

The Second

Restoration

The Bourbon restoration was a time of political instability

with the country constantly on the verge of political violence.

The army was committed to a defense of the Spanish monarchy

in 1824, achieving its aims in six months, but did not fully withdraw until

1828, in contrast to the earlier Napoleonic invasion this expedition was rapid

and successful.

Taking advantage of the weakness of the bey of Algiers

France invaded in 1830 and again rapidly overcame initial resistance, the

French government formally annexed Algeria but it took nearly 45 years to fully

pacify the country. This period of French history saw the creation of the Armée

d’Afrique, which included the French Foreign Legion. The Army was now uniformed

in dark blue coats and red trousers, which it would retain until the First

World War.

The news of the fall of Algiers had barely reached Paris in

1830 when the Bourbon Monarchy was overthrown and replaced by the

constitutional Orleans Monarchy, the mobs proved too much for the troops of the

Maison du Roi and the main body of the French Army, sympathetic to the crowds,

did not become heavily involved.

The Royal Army of the

Second Bourbon Restoration

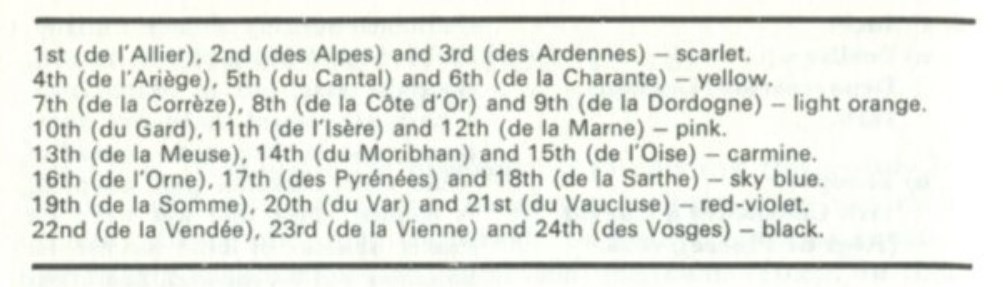

The Blue was reestablished in the Infantry with the

Regiments in 1820 when the Departemental Légions were disbanded, actually these

Légions had only one or two then 2 or 3 Infantry Battalions, a very small

number had really Scouts companies and the Artillery company existed only in

one Légion.

It was an (nearly)all-blue uniform with red collar for all

the régiments and after 1822 various regimental colours for the collar and

cuffs and white trousers for warm weather, so adopted before the first

campaigns outside France since 1815 (Spain in 1823, Greece, Algiers,

Belgium…)

The famous garance trousers were adopted in 1829 under

Charles X even if many people in France think that it was the Monarchy of July

who introduced it.

The 6 Swiss Regiments (2 of the Guard & 4 others)

disbanded in 1830 kept their traditional red uniforms.

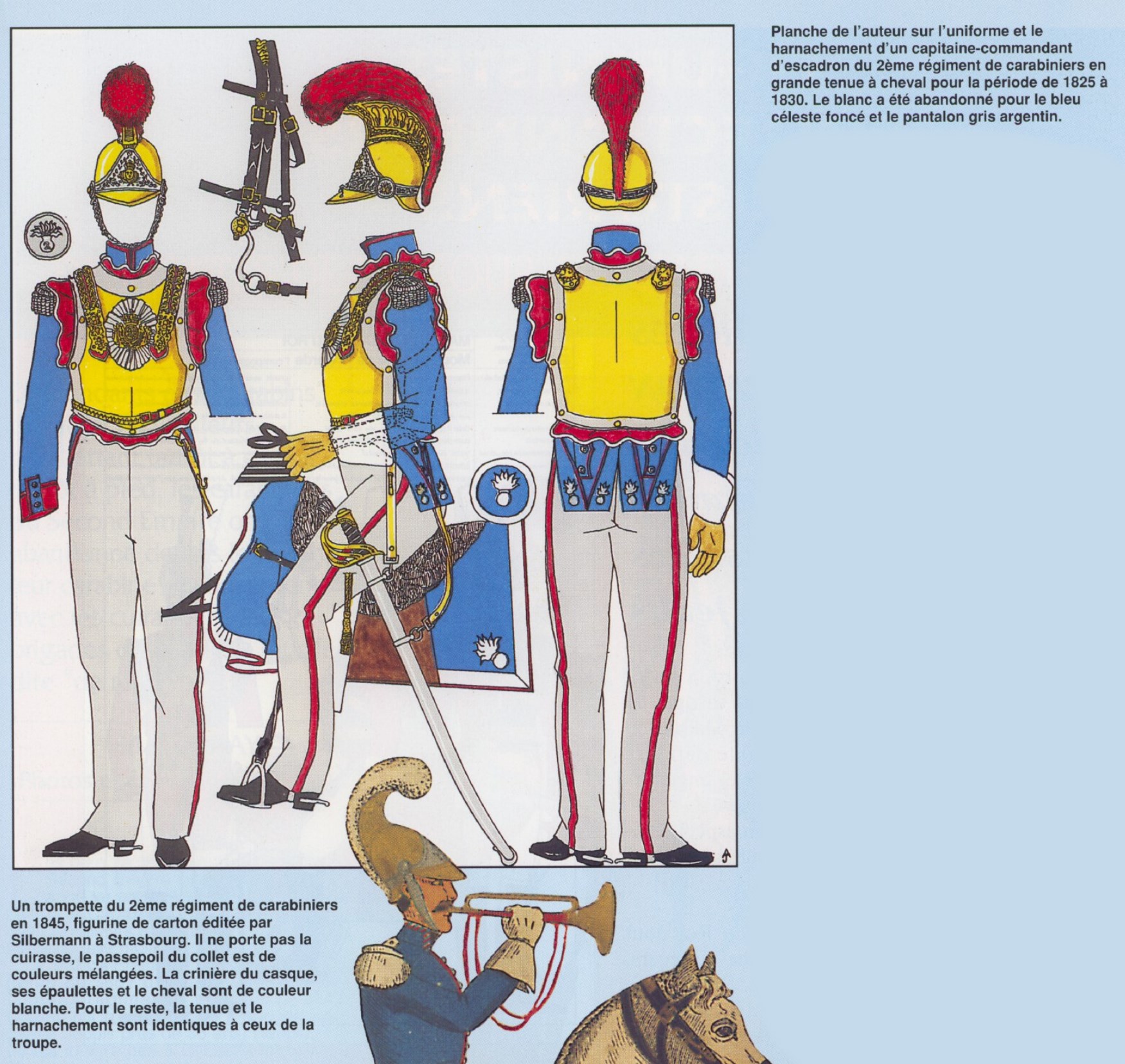

6. France: a) Fusilier, Departmental Legion 1816.

b) Trooper, 11th Chasseurs a Cheval (Régt de l’Isere), 1818.

Details of French infantry uniform changed a number of times

after the Bourbon Restoration, with often considerable delays in the adoption

of new patterns. A Bourbon shako-plate, issued to some units in the middle of

1814, was replaced upon Napoleon’s return by the old Imperial pattern (where

possible), which was itself replaced after Waterloo. After the second

Restoration came more drastic changes – the new Royal Guard continued to wear

blue, but the line regiments were completely reorganised into numbered

‘Departmental Legions’ each of three battalions, wearing a uniform of the 1812

pattern but in white with coloured facings, each of the eighty-six Legions

having a different arrangement of the colouring on collar, lapels and cuffs.

The facing colours were, for the 1st to 10th royal blue; 11th-20th yellow, 21st-30th

red, 31st-40th deep pink, 41st-50th carmine, 51st-60th orange, 61st-70th light

blue, 71st-80th dark green, and 81st-86th violet. The jacket turnbacks and

shako-plumes distinguished the various companies, fusiliers having

turnback-badges of the fleur-de-lys, voltigeurs of hunting- horn, chasseurs of

hunting-horn and fleur-de-lys, and grenadiers of the traditional bursting

grenade. Initially, the 1812 shako was worn with the 1814 Bourbon plate, but in

March 1816 a narrower-topped shako was introduced, and in 1818 metal instead of

white cloth cockades were adopted. A padded cloth disc was worn on fusilier

shakos, of blue for the 1st battalion, red for the and, and green for the 3rd

(until 1819 when extra battalions were added; then the 3rd took yellow discs

and the 4th green) with a brass company numeral on the disc. Grenadiers and

voltigeurs had pompoms of red and yellow respectively.

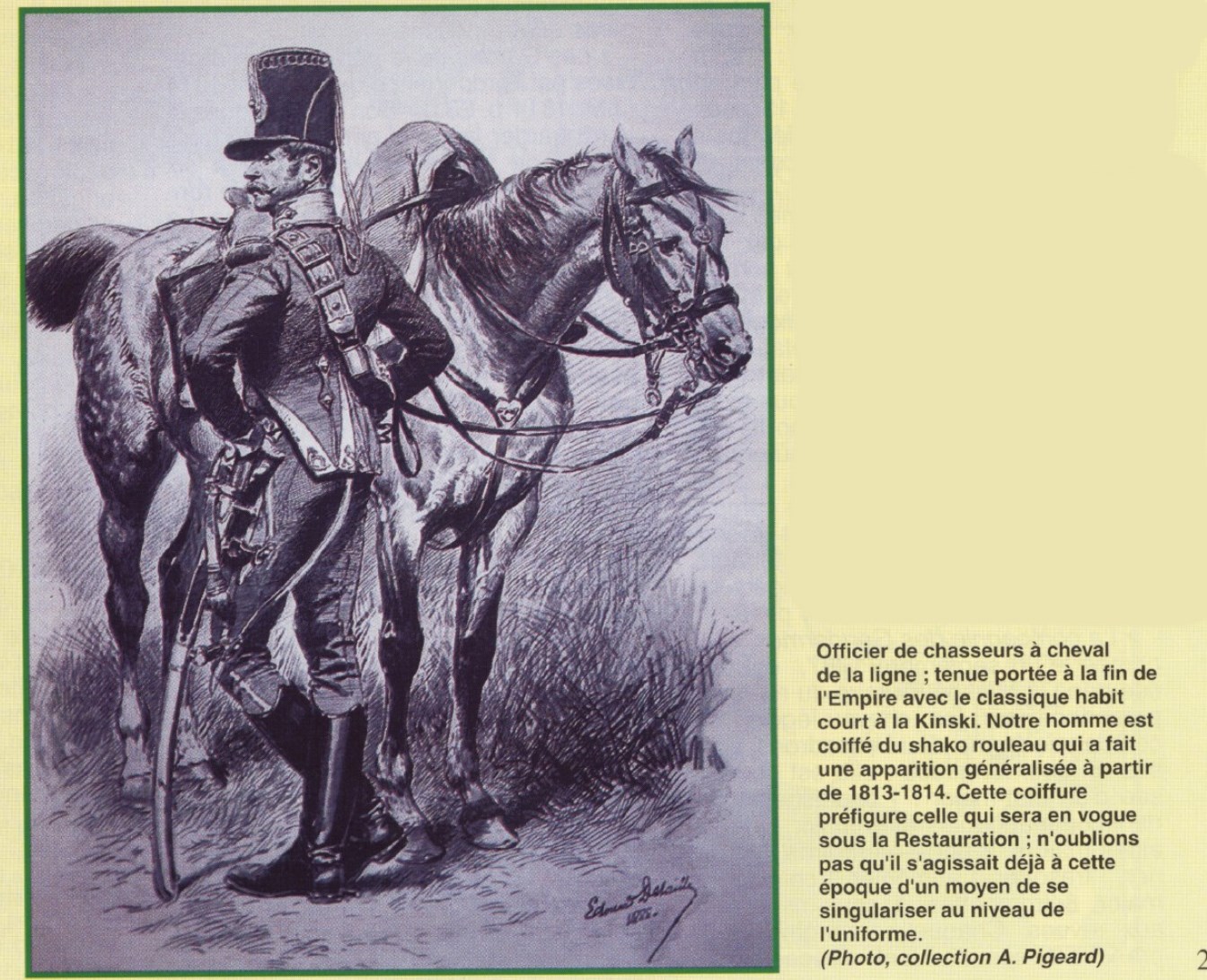

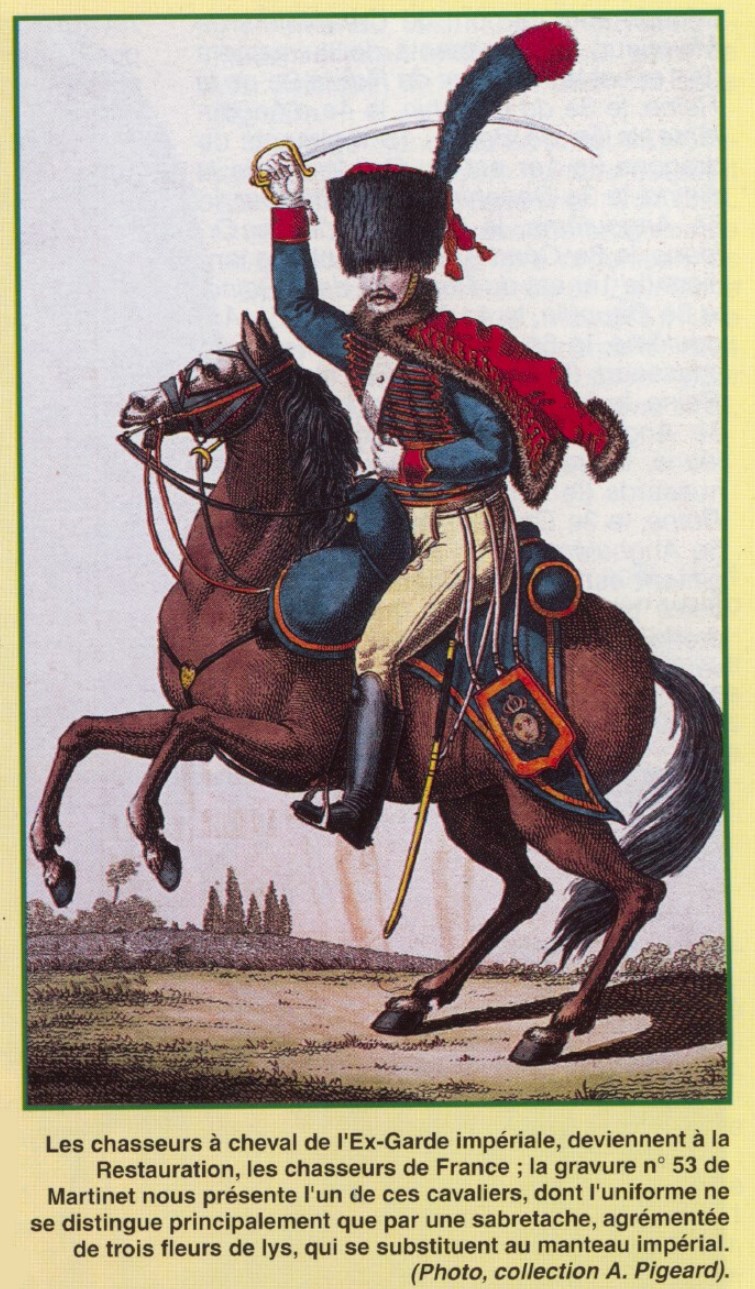

Chasseur a Cheval uniform changed considerably over the

years, these light cavalry troops in 1816 wearing lapelled jackets, having

Hussar-style braid by 1822 and becoming single- breasted in 1831. The tall,

cylindrical shakos had black plumes tipped with the facing colour, later

changed to falling black plumes, though pom- poms were also worn alone; in 1845

the busby was adopted at the same time as the red epaulettes (worn since 1831)

were changed to white.

Under the Bourbons, regiments again assumed titles as well

as numbers. Chasseur a Cheval regiments were organised in groups of three, the

first in the group having both collar and collar-piping in the facing colour,

the second with green collar and coloured piping, and the third with coloured

collar and green piping. In 1818 regimental names and facing colours were:

In 1822 this scheme changed, with regiments being grouped in

fours, the first two in each group having coloured collars with green piping,

and the last two in each group having green collars with coloured piping.

Facing colours at this time were: Ist-4th red 5th-8th yellow, 9th-12th carmine,

13th-16th blue, 17th-20th deep pink, 21st-24th orange.

An interesting feature of the uniform illustrated-taken from

a contemporary print by Canu is the elaborate method of wearing the

shako-cords.

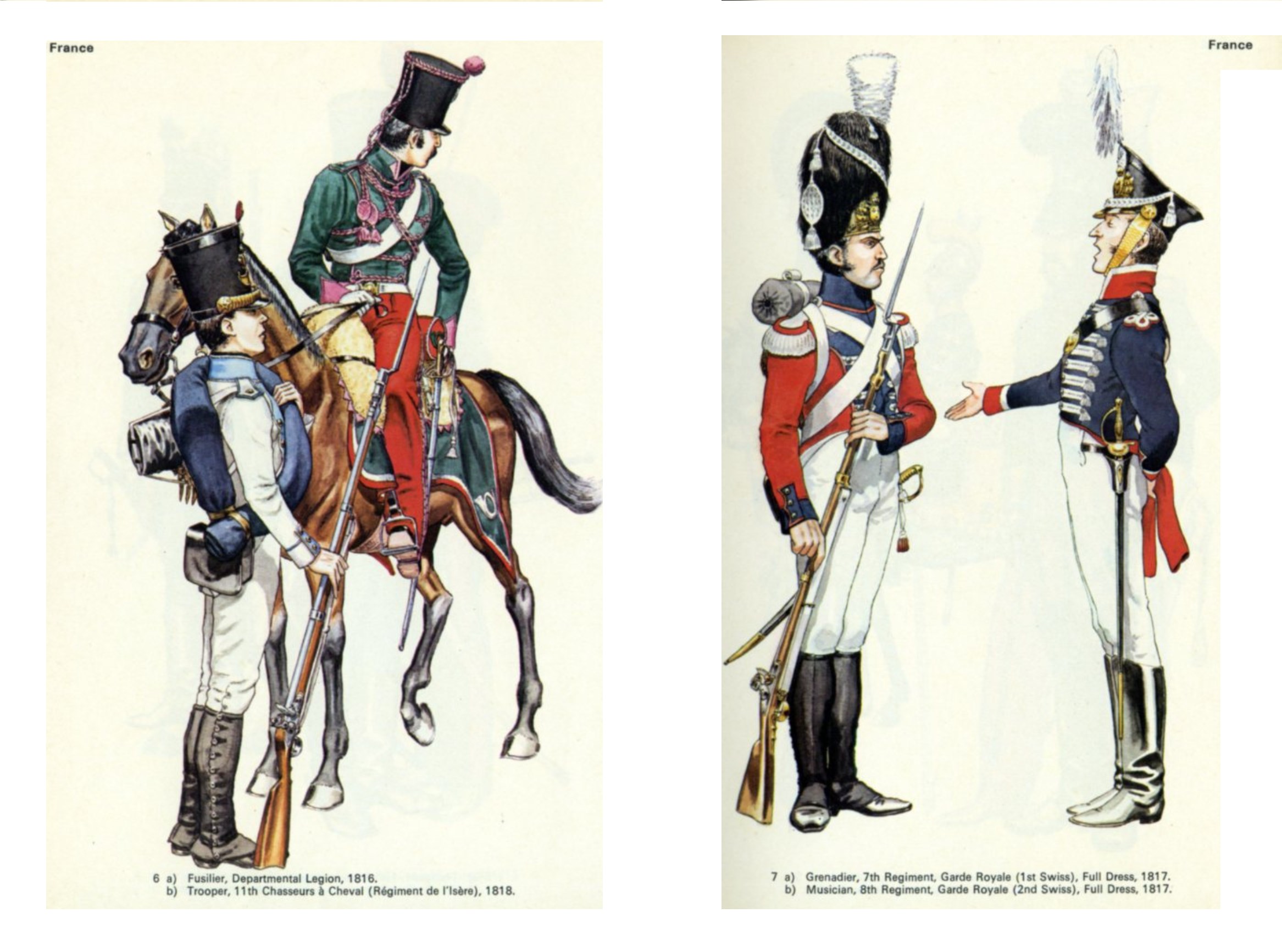

7. France: a) Grenadier, 7th Regt, Garde Royale (1st Swiss),

Full Dress, 1817

b) Musician, 8th Regt, Garde Royale (and Swiss), Full Dress,

1817.

It was traditional for the French Royal Guard to include

Swiss units, these troops being ranked among the King’s closest bodyguard prior

to the Revolution. Upon the first Restoration, a company of Cent-Suisses was

established, but not revived after the Waterloo campaign. Instead, of the eight

Guard infantry regiments raised upon the second Restoration, the 7th and 8th

were composed of Swiss and alternatively titled the 1st and 2nd Swiss

Regiments. Unlike the other six regiments (which wore blue uniforms) the Swiss

units continued to wear their traditional scarlet uniform, a colouring which

had been used during the Ancien Régime and by Napoleon’s Swiss corps; whereas

the grenadiers of the other Royal Guard regiments wore red epaulettes

(voltigeurs orange, centre companies white and chasseurs green), to prevent a

clash of colour between jacket and epaulettes the grenadiers of the Swiss

regiments continued to wear the white epaulettes of Napoleon’s day. All Royal

Guard infantry wore the lace loops on the breast; the fur cap was reserved for

grenadiers, the remainder wearing shakos.

Musicians (in every army) were traditionally distinguished

by unusual costume, the most frequent variation being that the body of the

uniform was of a different colour to that of the remainder of the regiment. The

uniform illustrated is no exception, being in the classic ‘reversed colours’

style (i. e. the body of the coat in the regimental facing colour and the

collar and cuffs in the usual coat-colour). An interesting feature of this

uniform is the shako, being reminiscent of the Russian ‘kiwer’ pattern, but of

a greater height. Shako-plates for musicians were frequently of a more

elaborate form than those of the remainder, in this case being a representation

of the Royal Arms with a trophy of flags around. The ‘trefoil epaulettes were a

common musicians’ distinction, dating from the Napoleonic period.

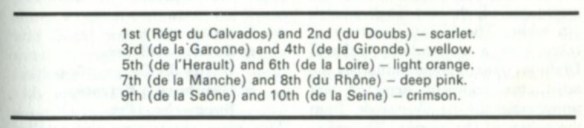

8. France: a) Trooper, Cuirassiers of the Garde Royale,

1820.

b) Trumpeter, 3rd Dragoons, (Régt La Garonne), 1818.

In 1815 a new helmet with caterpillar crest was adopted by

the French Dragoons, but was replaced by a pattern with horsehair mane authorised

in July 1821; but it seems likely that in some cases it was as late as 1825

before the new pattern was issued. The green uniform-colour associated with the

Napoleonic period was retained, regiments being allotted names and

facing-colours in a similar style to that of the Chasseurs a Cheval, described

in Plate 6. Names, numbers and facing-colours were as shown in the chart.

The uniform illustrated, however, shows an interesting

variation; an ornate trumpeter’s uniform with yellow helmet-crest (instead of

the usual black), and a blue uniform bearing regimental facings but with the

musicians’ lace of white with interwoven crimson ovals. The facing-colour was

also borne on the shabraque.

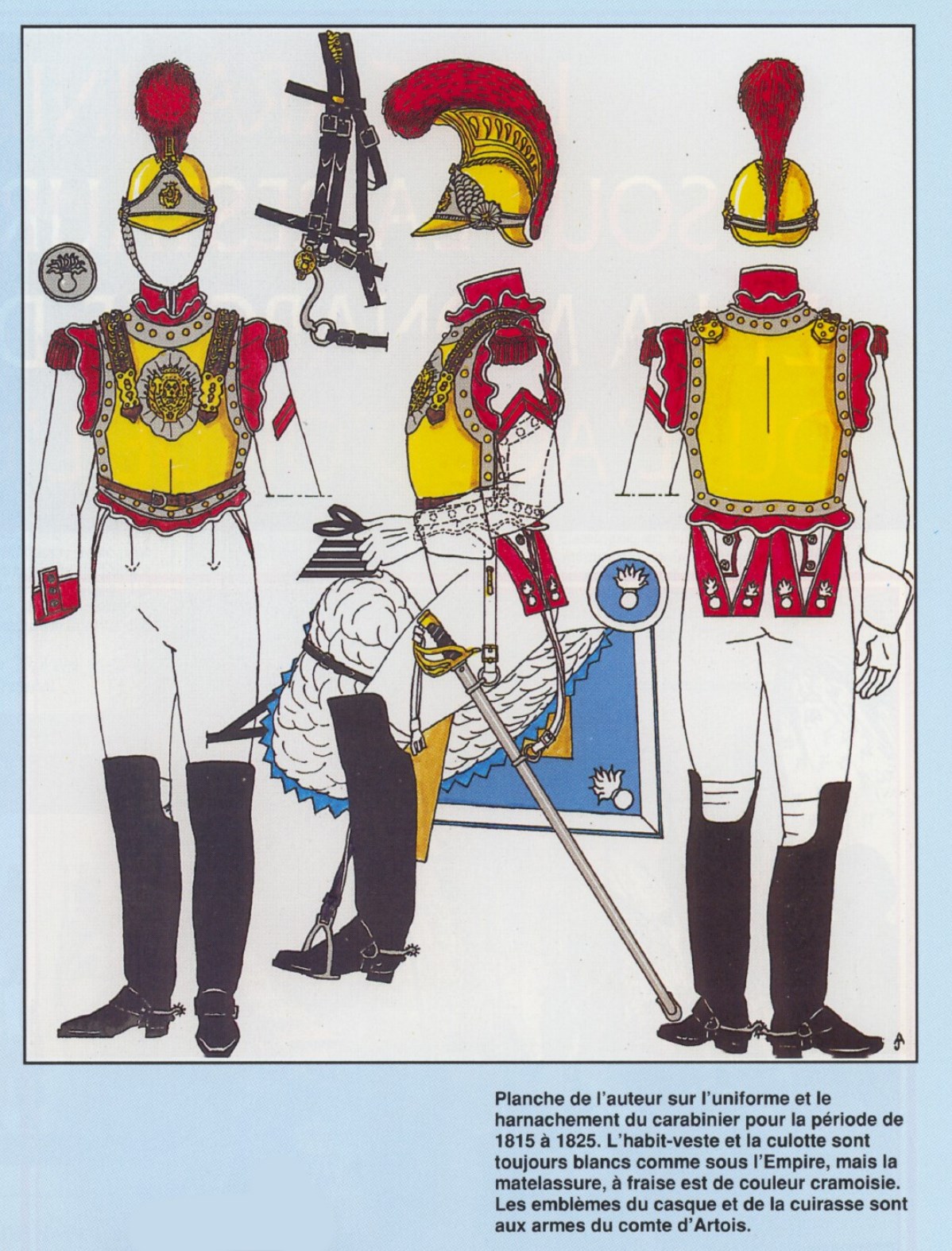

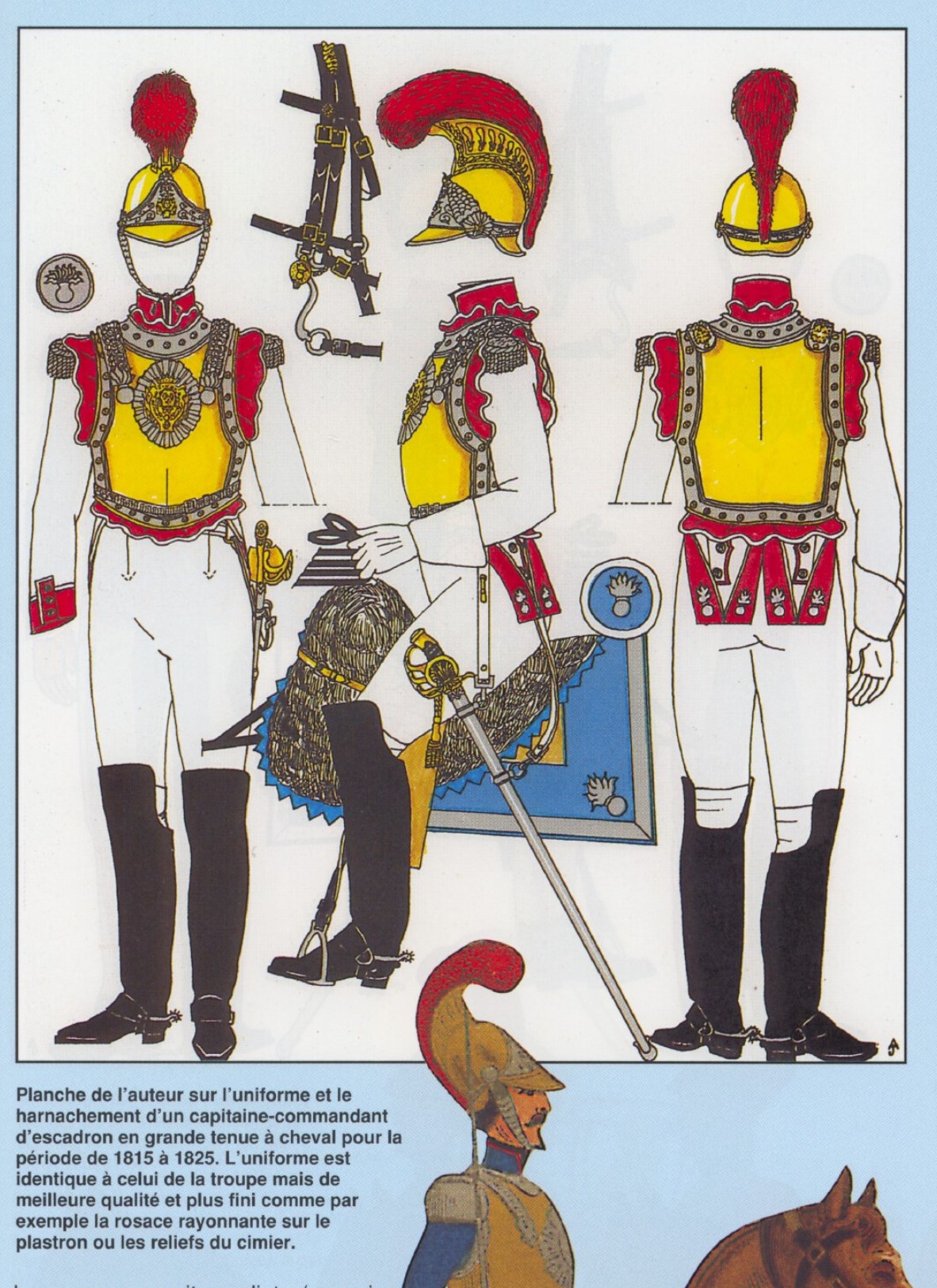

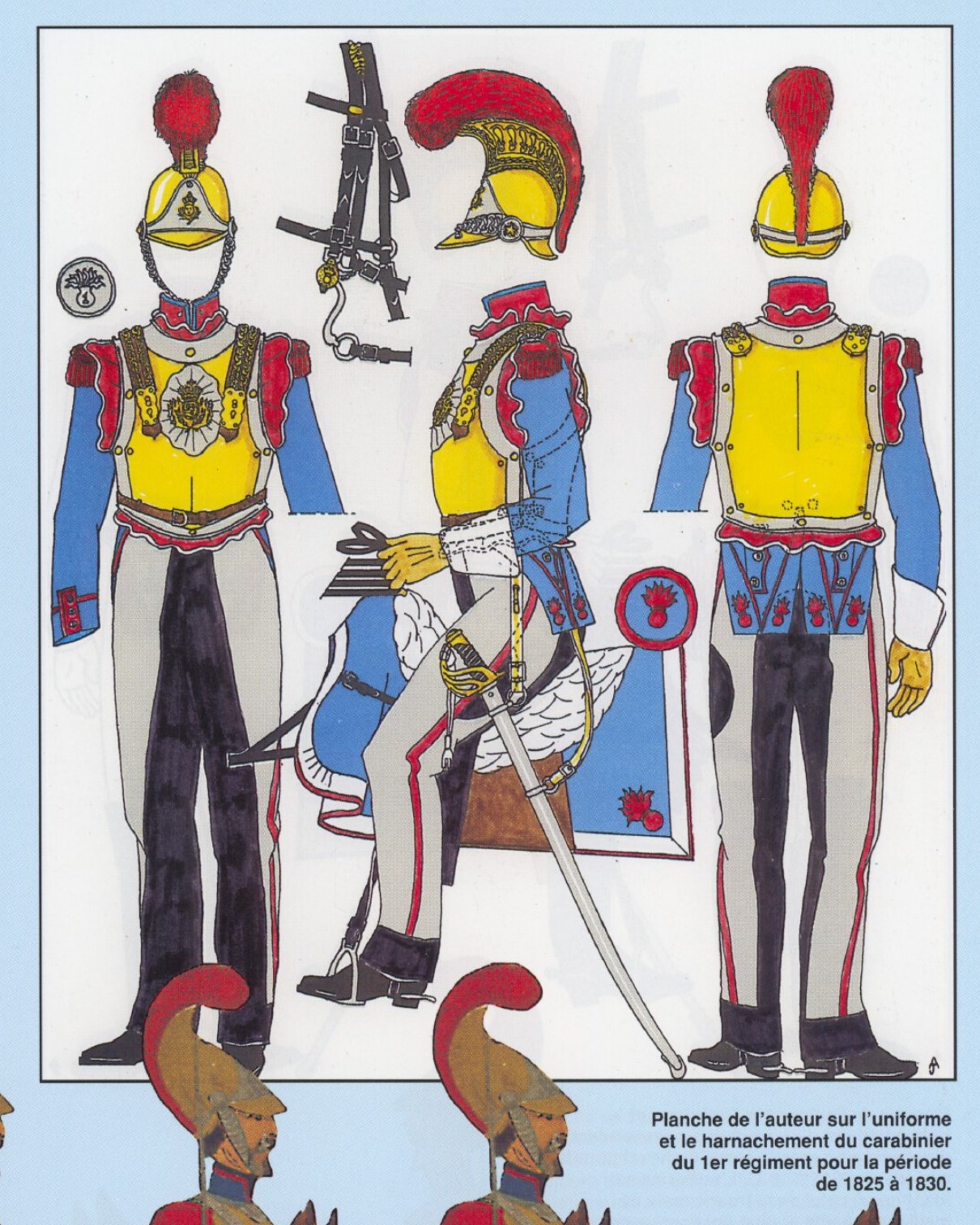

Though Napoleon’s Imperial Guard had included no

cuirassiers, the Bourbon Royal Guard did; two regiments, wearing almost

identical uniforms, strongly reminiscent of the cuirassiers of the Empire. The

helmets were of the old pattern, but with the horsehair mane replaced by a

cater- pillar plume, and the cuirass emblazoned with the Royal arms. Otherwise,

the costume might have belonged to a regiment of Napoleon’s. Both regiments had

white helmet- plumes, but the and had a red ball-tuft at the base. These

helmets were replaced in 1826 by a pattern lacking the skin turban, though the

and Regiment did not receive theirs until 1827

Other Guard cavalry regiments also wore uniforms based upon

those of their Imperial predecessors the Dragoons had brass helmets with

leopard-skin turbans, caterpillar crests and white plumes, green coatees with

rose-pink facings; the Horse Grenadiers had fur caps with white plumes for the 1st

Regiment and red-and- white for the 2nd, dark blue coats with white lace bars

on the breast, with red facings for the 2nd Regiment; and the Garde du Corps a

helmet similar to that of the old Gendarmes, with a red-faced blue uniform, each

company being distinguished in a singular manner, by coloured squares on the

pouch-belt. The first four companies to be raised had white, green, blue and

yellow belts respectively, and the 5th (when formed) scarlet.

15. France: a) Private, Marines, Undress, 1829.

b) Trooper, 8th Dragoons, 1827.

This plate illustrates the Dragoon helmet (also issued in

steel to the cuirassiers) which was authorised in 1821 but in some cases

probably not adopted until 1825, succeeding that shown in Plate 8. Of a most

unusual pattern, of the traditional Dragoon brass, it had a horsehair mane and

aigrette, and a hair ‘brush’ along the top of the crest. In 1826 squadron-identification

in the form of a coloured ball placed at the bottom of the plume was added, in

blue for the 1st squadron of every regiment, crimson for the 2nd, green for the

3rd, sky-blue for the 4th, rose-pink for the 5th and yellow for the 6th. This

helmet lasted until 1840, when it was replaced by a more conventional pattern

with ordinary mane and leopard-skin turban. The jackets remained the

traditional dragoon green in colour, but by 1823 new facing-colours had been

introduced, of deep rose for the 1st-4th Regiments 5th-8th yellow, and crimson

for the 3th and 10th. Trousers were grey with piping of the facing colour,

later changed to plain red for dismounted wear and red with leather reinforcing

for mounted duty, but it appears that there were variations in this rule; the

print from which this plate is taken shows red trousers with piping of the

facing colour!

The French Marines- organised in five divisions in May 1829-

wore a most singular uniform in both full and undress. The full-dress helmet

was an odd-shaped item, with a spherical black leather skull and brim like a

bowler, with a narrow brass crest supporting a black woollen crest, a brass

front plate and brass bosses on the side, embossed with fleur-de-lys motif, and

brass chinscales. The full-dress jacket was short, of dark blue with brass

buttons and shoulder- scales, worn with plain blue trousers black gaiters and

the same girdle as worn in undress. The undress uniform (chiefly remarkable for

the striped cap-band and chinscales) was worn with the same equipment as full

dress, having a black leather cartridge- box with brass anchor badge worn at

the rear of the girdle, in the middle of the back. Bayonet and brass-hilted

sword were worn in both orders of dress. The Divisions of Brest, Toulon and

(until 1832) Rochefort each maintained a band, the first two of great repute;

the drum-majors’ uniform included plumed busby, sash, mace, and a special

pattern of sabre The full dress helmet was abolished for wear at sea in 1832,

but remained in use for shore duty until 1840.

16. France a) Officer, 8th Regt, Garde Royale (and Swiss),

1829.

b) Drum-Major, 7th Regt, Garde Royale (1st Swiss), 1830

c) Bugler, Light Company, Infantry, 1828.

The Departmental Legions (Plate 6) were replaced in 1822 by

numbered infantry regiments in the previous manner, wearing single-breasted

dark blue jackets, white trousers for summer and blue for winter, and red

epaulettes for grenadiers, yellow for voltigeurs, and shoulder-straps for

fusiliers. In May 1822 facing colours were allocated to all 6o regiments, a

different combination of collar, cuffs, piping and turnbacks identifying the

individual corps. These colours were white for regiments 1-4, 5-8 crimson, 9-12

yellow, 13-16 rose-pink, 17-20 orange, 21-24 light blue, 25-28 buff, and 29-32

green, the colour-sequence repeating from the 33rd to 60th; regiments 61 to 64

were raised in February 1823. Another new shako- plate was introduced in 1821,

and a new shako n 1825, which had grenadiers and voltigeurs distinguished by

double pompoms of red and yellow respectively. In 1828 facing-colours were

abolished, all line regiments taking red facings, and light infantry yellow.

Musicians as usual disregarded the official regulations as

shown by the bugler in this plate; in 1827 the lace chevrons on the arms were

abolished, but are worn, though the authorised collar-and cuff-lace is not

musicians of fusilier companies often wore the epaulettes and plumes officially

reserved for flank companies while in many cases drum-majors still wore the fur

busby.

The two Swiss regiments of the Garde Royale illustrated show

the progression in costume from those shown in Plate 7. The musicians wore

reversed colours of blue with red facings, the bandsmen (though not drummers

and fifers attached to companies who wore the appropriate shako or grenadier

cap) having busbies; the jackets, now single- breasted, retained the bars of

lace on the breast. The drum major’s uniform illustrated was typical of the

opulent, lace-covered dress traditionally associated with French musicians.

Other Royal Guard infantry units adopted the

infantry-pattern jacket in 1822, retaining their distinctive lace and

grenadiers their bearskin caps, The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Regiments had cuffs and

turnbacks of crimson, rose- pink and yellow respectively, the 4th 5th and 6th

having the same facing-colour sequence but with blue cuffs, the facing colour

showing on the cuff- flaps and turnbacks only. Epaulettes were white for all

regiments, as were the shako- and grenadier cap-cords.

37 France: b) Private, Artillery Train, Garde Royale, 1824.

The uniform of the Artillery Train of the Royal Guard

illustrated is strongly reminiscent (in colouring) of its equivalent in Napoleon’s

army. The helmet, bearing the Royal arms on the front, was a development of the

style adopted immediately after Waterloo, being similar to the 1792 fur-crested

helmet originally copied from the British Tarleton.

Allied Occupation of France: 1815‒18 and the Royalist French Army is Rebuilt

Revolt in Spain

In January 1820, a liberal revolt led by Spanish troops

under General Rafael del Riego compelled absolutist King Ferdinand VII to

implement the Spanish constitution of 1812. That constitution – full of goodies

like universal suffrage (at least for men) and freedom of the press – had been

drafted by the Spanish national assembly (the Cortes) when they were trying to

rid the country of King Joseph Bonaparte and Napoleon’s troops during the

Peninsular War. Upon the constitution’s resurrection, Ferdinand became a de

facto prisoner of the Cortes. He retired to Aranjuez, south of Madrid. When a

counter-revolt by extreme royalists in July 1822 failed to liberate him,

Ferdinand called on the other European monarchs to come to his assistance.

The issue was taken up at the Congress of Verona in late

1822. The Holy Alliance (Russia, Prussia and Austria) was concerned about the

threat posed by revolutionary movements such as that in Spain, and Russian Tsar

Alexander I was keen to intervene. The British – represented at the Congress by

the Duke of Wellington – were opposed to intervention. Austrian Foreign

Minister Clemens von Metternich was in favour of restoring legitimate monarchs,

but did not want to give Russia an excuse to extend its power.

France was in an awkward position. As Ferdinand VII was a

member of the House of Bourbon, French ultra-royalists were pressuring King

Louis XVIII to rescue his distant cousin. Louis, however, disapproved of

Ferdinand’s brand of absolutism, and neither he nor Prime Minister Joseph

Villèle favoured sending troops into Spain. War would be expensive, the army

was not well organized, and the loyalty of the troops was questionable. As a

compromise, the government had already deployed soldiers along the border with Spain,

ostensibly to prevent the spread of yellow fever into France. This “cordon

sanitaire” became an observation corps.

France’s representative at the Congress of Verona, Foreign

Minister Mathieu de Montmorency, was on the side of the ultra-royalists. He

ignored Villèle’s instructions to limit discussion of the Spanish question.

Arguing that turmoil in Spain posed a threat to all of Europe, and especially

to France, Montmorency told the Congress that circumstances might force France

to recall her ambassador from Madrid, leading the Spanish Cortes to declare war

on France. He then asked whether, if France were compelled to engage in a

defensive war with Spain, she could count on the support of her allies. Russia,

Austria and Prussia agreed to provide moral and possibly material support.

Britain would not provide support. Instead, she offered to mediate between

France and Spain. The offer was refused. Amidst much hand-wringing over the

assault on Spanish liberty, Britain ultimately adopted a position of neutrality.

Though the way was paved for unilateral French intervention

in Spain, Villèle – backed by Louis XVIII – refused to go along with the plan.

Montmorency resigned. His replacement, François-René de Chateaubriand, also

favoured intervention, arguing that it would give France an opportunity to

regain great power status. There were fierce debates in the Chamber of

Deputies. Ultra-royalist pressure forced Villèle and the king to give in. On

January 28, 1823, Louis XVIII told the Chambers:

I have done every thing to ensure the

security of my subjects, and to preserve Spain from the extreme of misfortune.

The blindness with which the propositions, sent to Madrid, have been rejected,

leaves little hope of peace.

I have ordered the recall of my minister,

and one hundred thousand Frenchmen, commanded by a prince of my family, are

about to march and invoke the God of Saint Louis to preserve the throne of

Spain for a descendant of Henri IV, to save that fine kingdom from ruin, and to

reconcile her to Europe.

The Army of the Pyrenees, mobilized for the invasion –

actually numbered around 60,000. The problem of ensuring soldiers’ loyalty

without compromising their efficiency was dealt with by giving primary commands

to former Napoleonic generals (who had the necessary experience) and secondary

commands to royalists (who were unlikely to mutiny). Louis XVIII’s nephew, the

Duke of Angoulême was made commander-in-chief, despite his lack of military

experience. He was not keen on the appointment, but agreed to it as an

honourary post, leaving the army’s actual military direction to General Armand

Guilleminot, who had served under Napoleon.

The government hoped that victory over the revolutionary

forces in Spain would break the spirit of those who were conspiring against the

Bourbons in France. Many French political refugees, including some who had fled

to the United States and participated in the Vine and Olive Colony or the Champ

d’Asile, fought on the side of the Spanish constitutionalists. Among them was

the indomitable Charles Lallemand, who organized a Legion of French Refugees in

Spain.

At the beginning of February 1823, police spies reported

they had heard that:

Before the end of the month, Spain will

have organized an army of one hundred and eighty thousand men to oppose the

French invasion; this army will have for its vanguard a French legion, which

will march under tri-coloured flags; this legion will nominate a French regency

with Prince Eugène Beauharnais at its head….

The French army will be the scorn of all

Europe; it can hope for no success when commanded by a prince…who has no claim

on the confidence of true Frenchmen….

The first shot fired at the Pyrenees shall

be the signal for the downfall of the Bourbons in France, Spain and Naples.

Such are the hopes and prayers of the liberals in all countries.

On April 6, 1823, the question of the army’s allegiance was

answered. A group of insurgents led by Colonel Charles Fabvier tried to subvert

the French forces at the Bidassoa River who were preparing to enter Spain.

Fabvier’s group hoisted the tricolour flag, sang “La Marseillaise” and urged

the soldiers to desert the Bourbons. Instead the French troops obeyed General

Louis Vallin’s orders to open fire on Fabvier and his men.

The war

The next day, the French army entered Spain. They met little

resistance. As an Irish visitor to the country reported:

The Constitution, no matter what may be its

excellence or imperfection, has certainly not succeeded in gathering around it

the sentiments and good wishes of a majority of the people of that country. …

[A]pathy, to use the mildest expression, prevailed in all the towns through

which we passed after leaving Madrid. From my own observations, and those of

others, I can safely state that the great majority of the people on the line of

that route desired nothing so much as peace. They have been vexed and injured

by repeated contributions and conscriptions, and latterly, by anticipations of

the current year’s taxes, their means of complying with them being extremely

limited. … However ardent may be an Englishman’s wish that Spain may enjoy

liberal institutions (and if he were without a wish of this nature he would be

undeserving of his country); still, when he saw that the idea of civil liberty

was carried in that nation to an extreme which promised no durability, and that

this extreme, supported only by bayonets and by official employes, was the

inviolable system which England was called upon to assist with her mighty arm,

he cannot but rejoice that that assistance was refused, and that the strength

of his country was reserved for more worthy purposes. …

In the villages where I had occasion to

stop, I encountered no person who did not, at least, say that he was glad that

the French had entered Spain. The poor people I heard it more than once

observed, never liked the Constitution, because they never gained any thing by

it. Since it was established, they had known no peace, and they liked the

French, because they paid them well for every thing they consumed. It was also

observed, that since the establishment of the Constitution, this part of the

country was overrun with robbers; but that all that was now over, as the

robbers had disappeared since the French came.

The French soon controlled Navarre, the Asturias and

Galicia. Andalusia, the site of Cádiz (the constitutionalists’ provisional

capital, to which they had carried Ferdinand), took longer to subdue. On August

31, in the only significant battle of the campaign, the French took the

fortress of Trocadero and turned its powerful guns toward Cádiz. The city

surrendered on September 30. The Cortes dissolved itself and released Ferdinand

VII, who rejected the 1812 constitution, restored absolute monarchy and took

revenge on his opponents. In November, the Duke of Angoulême returned to

France, leaving behind an occupying force of 45,000. The last French soldiers

were not withdrawn until 1828.

French assault on Fort Trocadero

The expedition was considered a great triumph for the

Restoration. Chateaubriand wrote:

When I entered upon the foreign department,

legitimacy was about, for the first time, to launch its thunders under the

drapeau blanc, to strike its first coup de canon after those coups de l’empire,

which will resound to the latest posterity. If she recoiled, she was lost: if

crowned with mediocre success, she became ridiculous. But at one step to stride

over the Spains – to succeed where Bonaparte had been baffled – to triumph upon

that very soil whereon his armies had met with reverse – to do in six months

what he could not do in seven years – here is a true prodigy!

Villèle exploited the rush of grateful patriotism by

appointing a new batch of ultra-royalist peers and calling a general election

for early 1824. The left and centre were decimated, giving the ultra-royalists

a clear majority.

Louis XVIII, King

(1755-1824)

When Bonaparte seized power in 1799, royalists hoped he

would pave the way for a restoration of the Bourbon dynasty, in the person of

the pretender Louis XVIII. In the event, this younger brother of the

unfortunate Louis XVI would only succeed to the throne in 1814, after

Napoleon’s first abdication. By the time of his belated accession, contrary to

the famous jibe that he lived in the past, Louis XVIII had finally learned a

little and forgotten something of the old regime. His recent sojourn in Britain

had perhaps mellowed him, for under the Revolution there were few hints of any

moderation.

One of the first émigrés to leave France, in 1789, the comte

de Provence, as he was then known, was a die-hard reactionary who refused to

compromise with the principles of liberté, égalité, et fraternité. Indeed, on

the eve of the Revolution he urged his older brother to yield nothing to the

mounting opposition. Not surprisingly, the declaration he issued from his exile

in Verona (after having taken the title Louis XVIII on the death of Louis XVI’s

ten-year-old son, Louis XVII, in 1795) was a traditional defense of throne and

altar. Only a return to the absolutist and aristocratic system that had served

France so well for almost a thousand years, he argued, could save the country

from its dire predicament.

In the wake of the Terror, the moment for restoration

appeared ripe. Yet such an unbending appeal to the past disappointed most

resurgent royalists, who desired nothing more than a return to the

constitutional monarchy of 1791. Though the Republic seemed unworkable, the

extremism exhibited by Louis appeared equally unviable. Hence the attraction of

Napoleon, who was quick to quash rumors that he might be the French equivalent

of General Monck (restorer of Charles II in seventeenth-century England) by

stating that Louis would only march to power over thousands of French corpses.

The degree of internal stability that Napoleon achieved and,

above all, the reestablishment of the Catholic Church, ensured that Louis

remained isolated. The extrajudicial murder in 1804 of the duc d’Enghien-a

member of the House of Bourbon-closely followed by the creation of the hereditary

Empire, banished all hopes of a monarchical restoration to a post-Napoleonic

future, which materialized only with Napoleon’s defeat in 1814.

Even then the elderly, and rather portly, Louis had to

endure the indignity of scurrying back into exile when Napoleon launched the

adventure of the Hundred Days in 1815. It was still more difficult for Louis to

shrug off the accusation that he had returned in the baggage train of the

victorious Allies, a beneficiary of French defeat. There was also a severe political

backlash when Louis was restored for a second time, but he resisted pressure

from the so-called ultra-royalists and began to consolidate a liberal

parliamentary monarchy. It was the more reactionary policies of his younger

brother and successor, Charles X, that brought the Bourbons crashing down for

good in 1830.

References and further reading Dallas, Gregor. 2001. 1815:

The Road to Waterloo. London: Pimlico. Mansel, Philip. 1981. Louis XVIII.

London: Blond and Briggs.