Causes Following the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria unbent every effort to reverse its outcome and recover Silesia from Prussia. Her army, although still inferior to that of Prussia, had nonetheless performed well late in the war, and her resources were still formidable. The limitations of the British and Dutch alliance were evident, however, as the British saw Austria chiefly as an auxiliary against France, and Britain and the Dutch had contributed little military assistance to Austria. Maria Theresa now engineered what became known as the Diplomatic Revolution of the Eighteenth Century, dispatching Wenzel Anton Count Kaunitz as ambassador to France (1750- 1753) with the assignment of breaking the French-Prussian alliance.

In 1754 fighting had broken out in America and on the high seas between the British and French, and there was danger of this spreading to Britain’s German possession of Hanover. Still, it is doubtful that France would have allied with Austria without an action taken by King Frederick II of Prussia. Frederick was greatly alarmed by the general international situation. His seizure of Silesia ensured permanent Austrian hostility. Russia was also anti-Prussian. To counter a September 1755 treaty between Russia and Britain to protect Hanover against Prussia, Frederick signed with Britain the Statute of Westminster on January 16, 1756. In it he agreed to neutralize Germany and remove it from fighting between Britain and France.

This limited step had disproportion ate results. At the French court there was considerable anger concerning Frederick’s demarche toward Britain. There was also a sense that Prussia had become too powerful. The misogynist Frederick had also offended in well-publicized remarks not only Czarina Elizabeth of Russia but also Madame de Pompadour, influential mistress to Louis XV. On May 1, 1756, therefore, Louis XV concluded with Austria the First Treaty of Versailles. It bound each power to supply the other, if attacked, with an army of 24,000 men or its money equivalent. One consequence of this alliance was the marriage of the future French king Louis XVI to Marie Antoinette, daughter of Maria Theresa. Thus, whereas in 1740 Prussia and France had allied against Austria and Britain, in 1756 Prussia and Britain were allied against Austria and France. Nonetheless, the two major rivalries of Britain against France and Prussia against Austria continued.

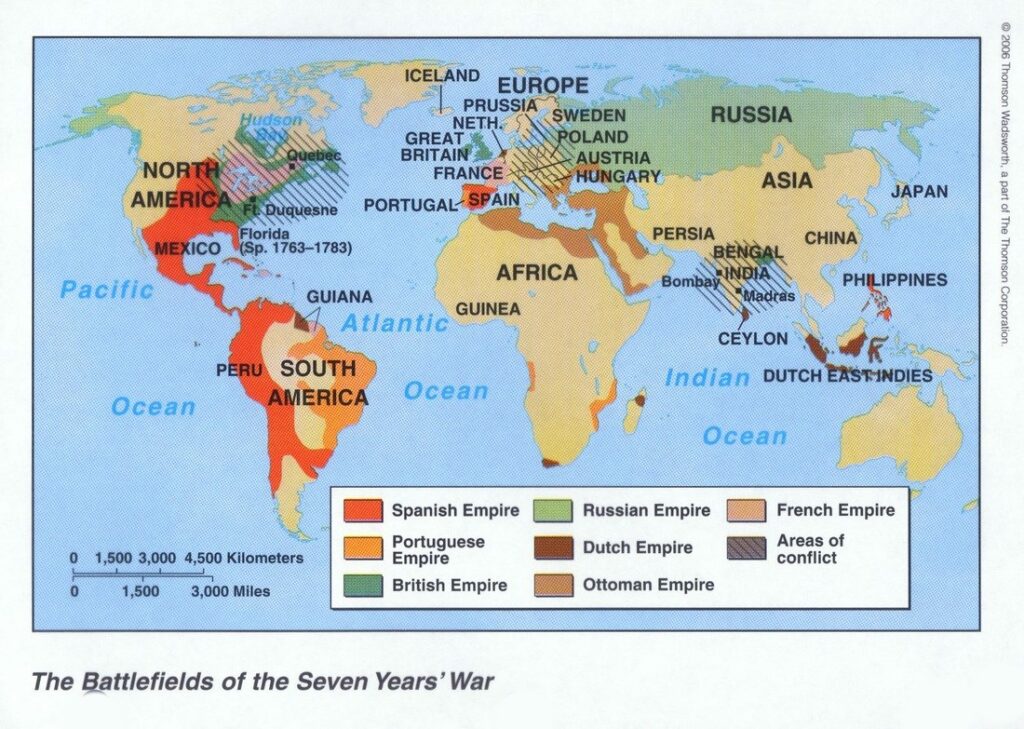

Frederick was well aware of the formation against him of what was arguably the most powerful military coalition of the century. Unwilling to wait until his enemies of Austria, France, Russia, and Saxony were ready to strike, he decided on a preemptive attack, beginning what would be the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Ultimately involving all the leading European powers, the conflict saw fighting across the globe: in North America, the Caribbean, and India as well as on the high seas. It also initiated for Prussia what would turn out to be the most desperate struggle for survival in 18th-century Europe.

Course

As noted, fighting had already begun between Britain and France in 1754. When the French invaded Minorca, Britain formally declared war on May 17, 1756. The two powers fought an inconclusive naval battle off Minorca on May 20 that led to a British naval withdrawal and British sur render of the island.

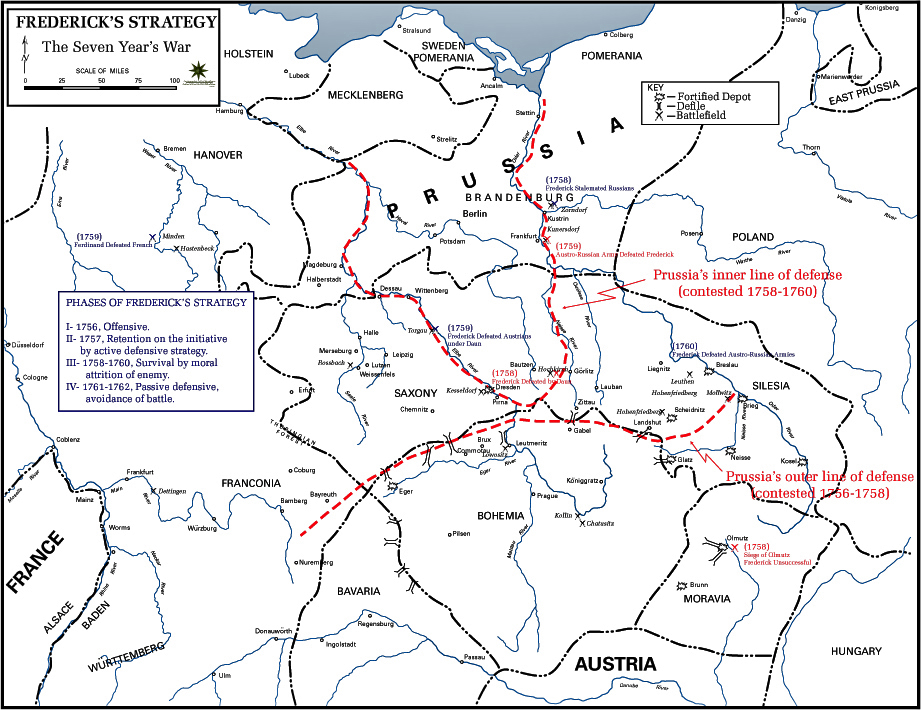

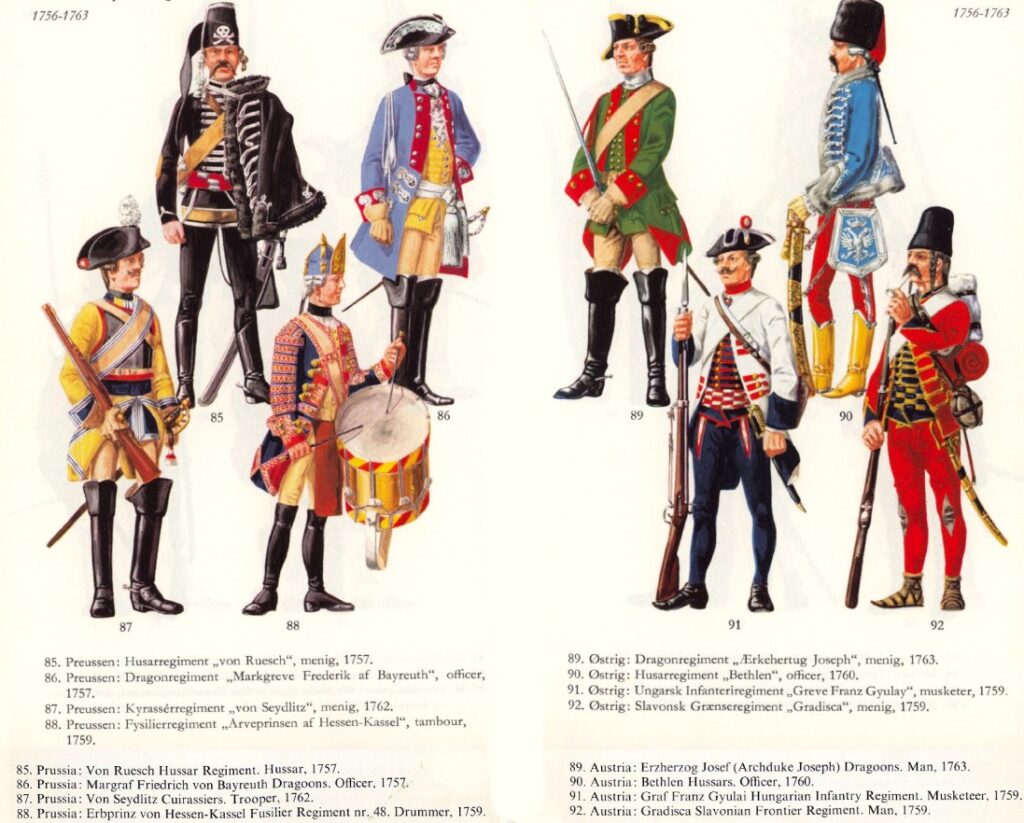

The Seven Years’ War and the Third Silesian War formally began on August 29, 1756, when Frederick mounted without declaration of war a preemptive strike against Saxony with 70,000 men. He captured the Saxon capital of Dresden on September 10 and then extracted large cash payments and drafted Saxons into his army, two practices he continued throughout the war. Frederick maneuvered brilliantly, moving rapidly and often surprising his opponents. His military genius was barely enough, however, as Prussia had as ally only Britain, which provided mainly financial subsidies.

Austrian marshal Maximilian von Browne advanced with 34,500 men to relieve some 14,000 Saxons trapped at Pirna on the Elbe. Frederick moved into Bohemia to oppose him with 28,500 men. The two armies met along the Elbe near Lobositz (Lovosice) on October 1. The battle began badly for Frederick but ended with an Austrian withdrawal. The Prussians suffered perhaps 700 killed and 1,900 wounded; Austrian losses were about 3,000. The Saxons at Pirna surrendered, and Frederick incorporated them into his army.

In April 1757 Frederick invaded Bohemia in force. He had some 175,000 men, half of them along the Bohemian frontier; the remainder were in defensive postures against France, Russia, and Sweden. Austria was then the only allied power ready militarily, and Maria Theresa had some 132,000 troops in northern Bohemia. In a risky maneuver, Frederick split his forces, sending some of his men across the mountains east of the Elbe and moving with the largest body from Pirna against Prague (Praha), where the Austrians had 55,000 men under Prince Charles of Lorraine.

On May 1, meanwhile, in the Second Treaty of Versailles, France agreed to a substantial increase in its military commitment. France pledged to maintain an army of 105,000 men in Germany as well as 10,000 German mercenaries and to pay Austria a large annual subsidy of 12 million florins. In return, France was to receive four cities in the Austrian Netherlands, with the remainder of the Austrian Neth erlands going to Don Philip, the Duke of Parma and Louis XV’s son-in-law. The cession of the Austrian Netherlands was, however, conditional on the Austrian recovery of all Silesia.

On May 6, Frederick with some 56,000 men faced 55,000 Austrians under Prince Charles and Marshal Browne near Prague and forced their withdrawal back into Prague. The fighting claimed some 13,400 Austrians and 14,300 Prussians. His resources insufficient to storm Prague, Frederick hoped to starve it into submission. Marshal Leopold von Daun now moved with an Austrian relief force to ward Prague. Taking 32,000 men from his forces besieging Prague, Frederick moved to block Daun with 44,000 men. The two armies met at Kolin (Kolin) in Bohemia on June 18. Daun had established a strong defensive position, and Frederick’s attack was poorly coordinated. After five hours of fighting Frederick withdrew, having sustained some 13,800 casualties, while Daun lost 9,000. This battle was Frederick’s first defeat of the war, and it forced him to abandon both his siege of Prague and plans to march on Vienna. Now facing some 110,000 Austrians, he had to abandon all Bohemia.

Austrian forces under Prince Charles and Marshal Daun crossed the Elbe on July 14. Frederick had not expected an attack from this direction and had given his brother Prince August Wilhelm command of forces on the east bank of the river. Advancing rapidly, on July 23 the Austrians captured the Prussian supply base of Zit tau in Saxony and there secured substantial provisions. Furious, Frederick relieved his brother of command.

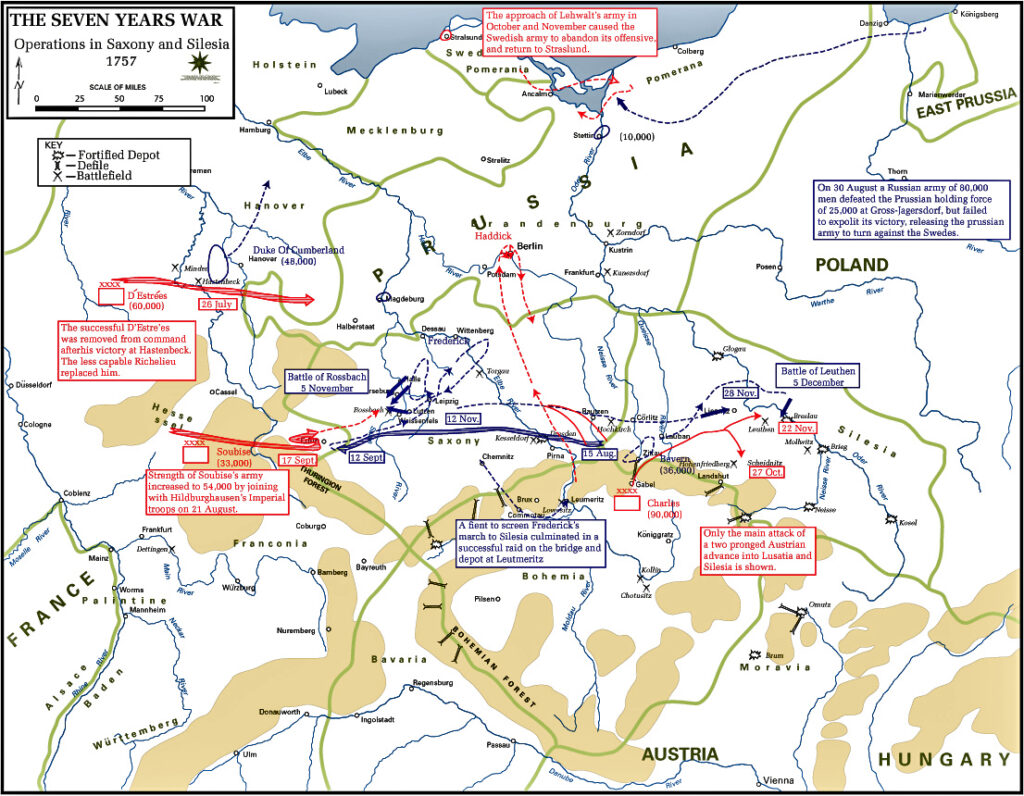

As the Austrians drove north into Saxony, Marshal Louis Charles César Le Tellier, Duc d’Estrées, invaded Hanover with a French army of 100,000 men in an effort to draw Prussian resources from the east. A second French army of 24,000 men under Marshal Charles de Rohan, Prince de Soubise, and 60,000 Austrians under Prince Joseph of Saxe-Hildgurhausen moved northeast into Franconia to join d’Estrées. Concurrently, Marshal Stepan Apraksin and a Russian army of 100,000 men invaded East Prussia, and 16,000 Swedes landed in Pomerania.

Pinned down in the east, Frederick was unable to assist in the west. This was left to the 40,000-man Hanoverian Army of Observation that included a majority from Hanover as well as men from Hesse and some Prussians. Duke William Augustus of Cumberland, son of King George II of Britain, had command. Cumberland re fused to defend the Rhine. His chief objective being to prevent the French from occupying Hanover, he concentrated behind the Weser River at Hamelin, hoping to prevent a French crossing.

The French took Emden on July 3 and Kassel (Cassel) on July 15. On July 16 they crossed the Weser in force, obliging Cumberland to do battle at Hastenbeck on June 26, 1757. D’Estrées had some 65,000 men, and the outnumbered Cumberland was forced to withdrew. The allies suffered 1,300 casualties, the French 2,600. This battle brought the French occupation of Hanover.

In the east, meanwhile, Field Marshal Stepan Fedorovich Apraksin and 75,000 Russians captured Memel. It became the principal Russian base for the invasion of East Prussia. The Russians then crossed the Pregel River. On August 30 Prussian Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt led 15,500 men in a surprise attack on a Russian corps, but other Russian forces quickly came up, forcing Lehwaldt to withdraw. While the Russians lost more than 5,400 men, Prussian casualties of 5,000 men and 28 guns lost were far heavier in percentage of forces engaged. The way to Berlin appeared open, and it was widely expected that Apraksin would move against Königsberg (present day Kaliningrad) and overrun all East Prussia, but he soon halted and then withdrew back into Russia. This was to support Peter III as heir to the throne but also because of a major outbreak of smallpox in the army and the collapse of the primitive Russian logistical system.

Leaving a small Prussian force in Silesia under August Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Bevern, Frederick rapidly marched westward with only 23,000 men to meet the most serious of the immediate allied military threats to his regime: the principal French army under Marshal Louis François Armand du Plessis, Duc de Richelieu, who had replaced Marshal d’Estrées; a second army of French forces under Soubise; and Austrian/ imperial forces under Prince Joseph Fried rich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen. Richelieu remained stationary, however, and Soubise and Hildburghausen, who had captured Magdeburg, withdrew to Eisenach on Frederick’s approach. Frederick then shifted direction to try to halt the Austrians under Prince Charles and Marshal Daun. On October 16, however, Austrian troops raided Berlin.

Learning that French forces under Soubise and Austrian-imperial forces under Sachsen-Hildburghausen had resumed their eastward movement, Frederick again marched westward. Departing Dresden on August 31 with 22,000 men, he covered 170 miles in only 13 days by arranging ahead for supplies and doing away with supply wagons. Crossing the Saale River, he drew the allies into battle in the vicinity of the village of Rossbach, west of Leipzig.

In the Battle of Rossbach of November 5, 1757, the two allied armies had together perhaps 66,000 men, Frederick only 22,000. The allies, moreover, occupied commanding terrain. Given their crushing numerical advantage, the allied commanders decided to envelop the Prussian east flank and sent three columns of 41,000 men south to accomplish this.

Guessing their intention, Frederick feinted a withdrawal eastward while slipping most of his forces south to his own left, a move concealed from allied observation by a line of hills. When the enveloping force completed its movement and swung northward, it met heavy Prussian artillery fire and the repositioned German infantry. At the same time, Prussian cavalry swung wide to the east and struck the right flank of the advancing allied columns. The Prussian infantry then smashed into the allied troops en echelon (in over lapping succession), completely routing them in less than an hour and a half. The Prussians suffered only 169 dead and 379 wounded. Allied losses were some 10,000, about half of them prisoners. Some 25,000 allied troops had not fought in the battle. Frederick’s brilliant victory removed the immediate threat to Prussia from the west and allowed him to shift his resources eastward to confront the Austrian armies advancing on Prussia from the south.

On November 22, Prince Charles of Lorraine and Marshal Leopold von Daun with 84,000 men encountered a Prussian army of 28,000 men at Wroclaw in Silesia under August Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Bevern, forcing it to withdraw west of the Oder after having sustained 6,000 casualties that included August Wilhelm, taken prisoner, to 5,000 for the Austrians. Wroclaw surrendered on November 25.

Having marched eastward 170 miles in only 12 days, Frederick joined what remained of Brunswick-Bevern’s force near Liegnitz (Legnica). With about 33,000 men, he moved east to meet the Austrians. Informed of Frederick’s approach, Prince Charles took up position with his 65,000 men near the village of Leuthen, a few miles from Wroclaw.

The Battle of Leuthen occurred on December 5, 1757. Frederick and his commanders were well familiar with the area, the site of Prussian military maneuvers. Outnumbered two to one, Frederick feinted a major attack on the Austrian right while he took advantage of a low range of hills to shift the bulk of his attacking force to the left. Charles took the bait, shifting reserves from his left front to his right to meet the threatened attack. Frederick’s infantry then struck the Austrian left. Charles endeavored to shift resources but was forced to withdraw. Nightfall ended the battle and rendered impossible any Prussian pursuit. The bulk of the Austrian forces escaped to Wroclaw.

The Battle of Leuthen shattered Charles’s army, which lost 6,750 killed or wounded, more than 12,000 captured, and 116 guns. Prussian losses were 6,150 killed or wounded. Frederick retook Wroclaw five days later, capturing another 17,000 Austrians. Both armies then went into winter quarters. Only half of the Austrian force that had begun the campaign remained.

In fighting in the west in 1758, on June 23 an allied German force of 32,000 men from Hanover, Hesse, and Brunswick under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick at tacked and defeated a 50,000-man French army commanded by Marshal Gaspard, Duke of Clermont-Tonnerre, at Crefeld (Krefeldt) in the Rhineland, northwest of Düsseldorf. The French withdrew to Cologne (Köln).

In yet another military embarrassment for the French, in August 1758 the British sent troops across the English Channel and destroyed port facilities at Cherbourg. Not satisfied, in September the British sought to attack St. Malo. Finding it too well fortified they withdrew, only to suffer more than 800 casualties while reembarking their raiding force.

In the east, in January 1758 Russian forces, now commanded by General Count Wilhelm Fermor, again invaded East Prussia but were brought to a halt by terrible road conditions. That spring Frederick campaigned in Moravia against the Austrians. In May he besieged Olmütz (Olomouc) on the Oder, defended by Marshal Daun. Frederick broke this off on July 1 on learning of the Russian approach. Carefully maneuvering to deceive the Austrians as to his real intent, he marched rapidly against the Russians.

Frederick arrived at the Oder across from Küstrin with 25,000 men and 167 guns as General Fermor and 43,000 Russians with 210 guns were laying siege to Küstrin, less than 100 miles from Berlin. Feinting a crossing of the river there, Frederick instead moved north in a night march, crossed the river, and in a wide turning movement threatened Fermor’s lines of communication back to Russia. Learning of the Prussian moves, Fermor lifted the siege and took up a defensive position facing north at the Prussian village of Zorndorf (now Sarbinowo, Poland), about 6 miles southeast of Küstrin.

The August 25 Battle of Zorndorf has sometimes been referred to as the bloodiest battle of the century. The Russian infantrymen doggedly refused to withdraw, and large numbers were cut down where they stood. Fighting continued until nightfall. The Prussians lost 12,797 men, the Russians some 18,500. The battle was a draw, although Fermor’s withdrawal two days later allowed Frederick to claim victory. The battle was strategically important, as it prevented the Russians from linking up with the Austrians and perhaps defeating Frederick once and for all.

This was not the end of fighting in the east that year. Learning that Austrian forces under Marshal Daun were threatening those under his brother Prince Henry of Prussia near Dresden, Frederick II hurried there with his part of the army, arriving on September 12. The Austrians then withdrew. Now having 31,000 men, Frederick commenced offensive operations, only to be surprised and surrounded by a secret night march by Daun and 80,000 Austrians at Hochkirch, about five miles east of Bautzen in Saxony.

Daun attacked at dawn on October 14, employing his own oblique attack. Despite a nearly threefold disadvantage in manpower, the Prussians fought hard, and their cavalry managed to open an escape route through the Austrian lines. Most of the army escaped but at the cost of 9,097 dead, wounded, or captured. The Austrians also secured 101 Prussian guns. Austrian casualties totaled 7,587. Daun then laid siege to Dresden. Learning that Frederick had reconstituted his army and was marching against him, Daun raised the siege and retired into winter quarters at Pirna. The end of the year saw Frederick in firm control of both Silesia and Saxony. Both the Russian and Swedish forces had evacuated Prussian territory. The year 1758 had nonetheless been costly for Frederick. Although he could still field 150,000 men, the campaigns of 1758 had cost him 100,000 of his best-trained men, and the army was no longer the quality of the year before.

In western Germany in 1759, April 13 saw an allied force of 35,000 men under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick attack at Bergen near Frankfurt-am-Main a French force of 28,000 men commanded by Marshal Victor François, Duc de Broglie. Rebuffed, the allies withdrew in good order. The French then seized the bridges over the Wesel and advanced to Minden. On July 25, French forces under General Louis de Brienne de Conflans, Marquis of Armentieres, captured Münster in present-day Rhine Westphalia, taking 4,000 allied prisoners.

The French then concentrated some 60,000 men near Minden under Marshal Louis Georges, Marquis of Contades. On August 1, 1759, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick led 45,000 allied troops, including 10,000 Britons, against the French, driving them off. The Battle of Minden cost the al lies some 2,800 casualties; the French sustained 10,000-11,000 as well as the loss of 115 guns. Ferdinand pursued the French almost to the Rhine, halting only when Frederick ordered him to send men east. The Duc de Broglie replaced Contades, who was sacked.

In the east, in July 1759 Russian General Pyotr Saltykov led 47,000 men from Posen along the Oder River toward Crossen. Frederick II ordered Prussian Lieutenant General Karl von Wedel and 28,000 men to stop the Russian advance. Saltykov defeated Wedel on July 23 in the Battle of Kay (Paltzig, now in Poland). The Prussians suffered 8,300 casualties to 6,000 for the Russians. Saltykov then crossed the Oder and occupied Crossen.

Frederick was determined to prevent the Russians from joining the Austrians. Before he could carry this out, however, some 18,500 Austrians under Lieutenant Field Marshal Ernst von Laudon (Loudon) joined Saltykov’s 41,000 men east of Frankfurt an der Oder. Frederick, with 50,900 Prussians, crossed the Oder and on August 12 attacked the entrenched allies in hilly terrain at Kunersdorf (present-day Kunowice, Poland).

Frederick attempted a simultaneous double envelopment. Owing to his men’s inadequate training and woods that imposed delay, the attacks occurred piece meal, but Frederick insisted on continuing the attacks and was defeated. Frederick himself barely escaped capture. Shocked by their own heavy casualties, however, the allies failed to exploit their victory. Russian and Austrian losses totaled 15,700 men (5,000 killed), but the Prussians suffered 19,100 casualties (6,000 dead) and lost 172 guns. Much of what remained of the Prussian army was scattered; indeed, immediately after the battle, Frederick had only 3,000 men under his direct command. Kunersdorf was the worst defeat of Frederick’s military career.

Within a few days most of Frederick’s scattered forces rejoined him, bringing his strength to 32,000 men and 50 guns. Receiving reinforcements from Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, Frederick regained his determination. The Russians, having exhausted forage and other area resources, retired to the frontier. Frederick therefore decided to move against Marshal Daun’s Austrians, who had captured Dresden on September 4.

Frederick sent 14,000 men under General Friedrich August von Finck to cut the Austrian lines of communication with Bohemia. Frederick expected Daun to withdraw once this occurred, but Daun trapped Finck. Outnumbered 42,000 to 14,000, Finck sur rendered his entire force on November 21. Both sides then went into winter quarters.

The French had hoped to invade the British Isles in 1759, but to accomplish this they would have to join their Mediterranean and Channel Fleets. British admiral Sir Edward Hawke commanded the Channel Fleet confronting the French Brest squadron. Admiral Sir Edward Boscawen, charged with containing the French Toulon Squadron, defeated it in the Battle of Lagos (August 18, 1759). The Brest Squadron remained a major threat, however.

On November 14 a storm drove the British blockaders off station, and French admiral Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans, sortied from Brest with 21 ships of the line. Hawke was soon in pursuit with 24 ships of the line. Surprised by Hawke on November 20 southeast of Belle Isle on his way to escort transports carrying troops to Scotland, Conflans was unable to form a line of battle and tried to escape into the Vilaine estuary, utilizing pilots familiar with the coast to take him into the wind swept and rocky lee shore. In terrible conditions Hawke signaled a general chase, and his ships followed the French into Quiberon Bay. In the ensuing battle fought in high winds and torrential rain, the French lost 4 ships of the line and 1,300 men killed.

Hawke anchored for the night, intent upon destroying the remaining French ships come daylight. In the dark, however, eight French ships escaped to Rochefort, where they remained for the rest of the war. Seven others lightened ship and entered the Vilaine estuary, where they were stranded for a year. Conflans was forced on the morning of November 21 to run his own ship on the rocks rather than have it taken by the British.

The Battle of Quiberon Bay cost the French six ships of the line wrecked or sunk and 1 captured, along with 2,500 dead. The British lost two ships of the line wrecked and 400 dead. The battle ended any French threat of invasion of the British Isles for the rest of the war. It also prevented the French from resupplying or augmenting their forces in North America. Although French privateers continued to enjoy success against British merchant shipping, the French Navy was largely swept from the seas.

During the winter of 1759-1760 the allies planned for a series of coordinated attacks in the spring to destroy Frederick. The Austrians concentrated 100,000 men under Marshal Daun in Saxony and 50,000 men under Marshal Laudon in Silesia. Laudon was to cooperate with 50,000 Russians in East Prussia under Marshal Saltykov. If Frederick turned on any one of these, the others were to move against Berlin. Frederick was on the Elbe with 40,000 men facing Daun, Prince Henry was in Silesia with 34,000 men, and an additional 15,000 Prussians opposed other Russian and Swedish forces ravaging Pomerania. In the west, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick commanded an allied army of 70,000 men in Hanover opposing some 125,000 French troops.

The Prussians suffered their first reverse on June 23, 1760, when Marshal Laudon with some 28,000 men defeated Prussian general Henri de la Motte Fouqué with 11,000-12,000 men at Landshut in Silesia. During July 13-22 Frederick attempted to engage both Laudon, be sieging the Prussian fortress of Glatz (now Klodzko in Lower Silesia, Poland), and Daun. When Frederick threatened Laudon, Daun marched to his assistance. Frederick then quickly countermarched and attempted to recapture Dresden. The Prussians shelled the city, inflicting considerable damage, but failed to bring about an Austrian surrender. On July 21 Daun reinforced Dresden, obliging Frederick to abandon his operations there. Then on July 26, Laudon’s Austrians captured Glatz.

Laudon next moved against Wroclaw, held by 4,000 Prussians under General Bogislav von Tauentzien with 9,000 Austrian prisoners. Laudon laid siege to Wroclaw on July 30 but, facing the imminent arrival of Prussian reinforcements under Prince Henry, raised it on August 5. Salykov’s Russians were still five days’ march away.

Calling on Prince Henry to join him, Frederick II led 30,000 men into Silesia. Laudon with 24,000 men and Daun with 36,000 pursued, and the chances appeared good that Count Zacharias Chernyshev would join them near Wroclaw with 25,000 Russians.

The Prussians and Austrians met near the large Silesian city of Liegnitz. The Austrians planned a double envelopment, with Laudon taking a blocking position to hold Frederick in place. On the night of August 14-15 in a brilliant march, however, Frederick shifted position so that when Laudon launched his attack before dawn on the morning of August 15, it was the Prussians who enveloped and defeated him before Daun could come up. Frederick then cut his way out, having inflicted some 8,500 Austrian casualties and captured 80 guns for losses of only 3,394 men. Although his men were fresh, Daun decided not to attack on his own, missing an excellent opportunity to destroy Frederick with superior forces. A false report by Frederick led Chernyshev to believe that the Austrians had been totally defeated, causing him to withdraw. Frederick then maneuvered against Daun.

During October 9-12, 1760, meanwhile, 20,000 Russians under General Gottleb Tottleben and 15,000 Austrians under Marshal Franz Moritz Lacy briefly occupied Berlin. On October 9 also, Russian troops ambushed Prussians retreating from Berlin to Spandau, killing or capturing 3,300. The allied occupation of Berlin was mild, no doubt because Tottleben was carrying on a treasonous correspondence with the Prussians. Although private residences were sacked and the occupiers secured a ransom of 1.5 million thalers, the only significant damage to the Prussian war effort was destruction of the city’s gunpowder plant. With Frederick hurrying there, the allies evacuated Berlin.

Learning that Daun was concentrating some 52,000 men near Torgau, Frederick assembled 44,000 men and moved against the entrenched Austrians, attacking on November 3. Concentrated Austrian artillery fire claimed 5,000 Prussian grenadiers in only one hour, and Frederick called off the assault, believing the battle lost. Marshal Lacy replaced Daun, wounded in the foot, and the battle turned that evening when Prussian General Hans von Zeiten attacked and captured much of the Austrian artillery, then turned these guns against the Austrians. That night Lacy withdrew to ward Dresden. This Prussian victory came at heavy cost, however: 16,670 casualties against Austrian losses of 15,000 (7,000 of them prisoners) and 43 guns. Both sides then went into winter quarters.

In western Germany in 1760, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick sought to emulate Frederick with a series of rapid marches and maneuvers to keep French forces separated and allow him to defeat them in detail. In the Battle of Warburg in present day North Rhine-Westphalia on July 31, 1760, Ferdinand and some 16,000 men defeated French lieutenant general Chevalier du Muy with 20,000 men. The French suffered between 6,000 and 8,000 casualties and lost 12 guns. The allies sustained 1,200 casualties. French marshal de Broglie took advantage of Ferdinand’s absence to seize Kassel (Cassel), however.

In early autumn with the French threatening to invade Hanover, Duke Karl Wil helm Ferdinand and some 20,000 men marched against the French-held fortified town of Wesel at the juncture of the Rhine and Lippe Rivers. The French defenders destroyed key bridges, and Lieutenant General Charles Eugene Gabriel de La Croix de Castries, Marquis de Castries, moved to relieve Wesel but then decided to await additional reinforcements before attacking.

Determining that he could not take Wesel by storm, Duke Ferdinand ordered up heavy siege and bridging equipment. In the meantime, he planned to attack de Cas tries with a movement around the French left flank at Kloster Kamp during the night of October 15-16. The allied assault early on October 16 enjoyed initial success, but de Castries rushed up reserves and counter attacked, carrying the day. Ferdinand then fell back toward the Rhine, but the bridge of boats he had ordered constructed there was swept away by the fast flowing river, stranding his army on the west bank for two more days. De Castries chose to await reinforcements and failed to exploit the situation. The French suffered 3,123 casualties, while the allies lost 1,615. The battle ended the Siege of Wesel, and the opposing west ern armies then went into winter quarters.

In the summer of 1761, Frederick learned that Austrian forces under Marshal Laudon and Russians under General Aleksandr Buterlin had joined near Liegnitz. Frederick then dug in at Bunzelwitz in Silesia some 20 miles east of Glatz in the Eulen Gebirge (Owl Mountains). In only 10 days and nights, Frederick’s men turned this natural fortress on the northern frontier of today’s Czech Republic into a formidable defensive position. Still, Frederick had only 53,000 men against some 130,000 for the allies.

Laudon drew up a detailed plan for a massive attack that had an excellent chance of success, but Buterlin rejected it, his caution the result of two factors: Russian empress Elizabeth had sent a message in June during the army’s march through Poland indicating that she would like to see it return to Russia intact, and Elizabeth was in failing health, with the heir apparent an unabashed admirer of the Prussian king. The inability of the allies to agree on a plan of action in addition to an unusually hot summer and a near total lack of forage for the horses led the Russians to withdraw back to the Oder beginning on September 9.

Laudon was able to salvage something from the frustrating 1761 Silesian campaign, however. Acting on information provided by an escaped Austrian prisoner, Laudon moved against the important Prussian-held fortress of Schweidnitz in late September, storming and capturing it on September 30 without preliminary bombardment, taking 3,800 Prussians prisoner, and depriving Frederick of his best-placed and most important Silesian supply depot. For the first time in the war Austria held significant areas of Silesia during the winter, forcing Frederick to remain in Silesia instead of wintering in Saxony as he desired.

In the west in 1761, two French armies totaling 92,000 men under Marshal de Broglie and Marshal Soubise, attempted to force the allies from Lippstadt. On July 15 the French attacked an entrenched al lied force of 65,000 German and British troops under Duke Ferdinand at Villinghausen, near Hamm in present-day North Rhine-Westphalia. With the two French commanders of equal rank and each reluctant to take orders from the other, the French withdrew. The allies suffered some 1,400 casualties, the French 5,000. By October, however, the French had pushed al lied forces east to Brunswick.

Winter set in early that year, and morale was low among the Prussian forces, with soldiers deserting in large numbers. There was even a plot to assassinate Frederick. In Saxony, Prussian prince Henry was holding his own against the Austrians under Marshal Daun, but in western Germany the situation appeared precarious. British king George II died on October 15, and his successor, George III, began withdrawing some British troops from the continent and threatened an end to subsidies to Prussia. Frederick now had only 60,000 men, and the end appeared near.

The war had also expanded that fall. France and Spain concluded a pact against Britain in August 1761, and Spanish and French troops invaded Portugal in October. Britain came to the assistance of Portugal and declared war on Spain in January 1762.

With the end for Frederick apparently near, on January 5, 1762, there occurred the so-called Miracle of the House of Brandenburg. Czarina Elizabeth I died. Her successor, the mad Peter III, an unabashed admirer of Frederick, immediately with drew Russia from the war. On May 15 in the Treaty of St. Petersburg, Russia concluded peace with Prussia and agreed to evacuate East Prussia. Czar Peter even loaned Frederick a Russian army corps.

Russia’s decision to withdraw from the war caused Sweden to follow suit. In the Treaty of Hamburg of May 22, Prussia and Sweden concluded peace on the basis of status quo ante bellum. Frederick was now free to concentrate against Austria, while Duke Ferdinand held the French at bay in the west.

On June 24, 1762, at Wilhelmsthal in Westphalia, Duke Ferdinand’s allied army of 50,000 men defeated a French army of 70,000 commanded by Marshal Louis Charles d’Estrées and Marshal Soubise. The allies almost encircled the French before they escaped and withdrew across the Fulda River. The French suffered some 3,500 casualties, while the Allies suffered 700.

Taking advantage of anger over Czar Peter III’s pro-Prussian policies and fearful that he intended to divorce her, Peter’s wife Catherine and her lover Grigori Orlov led a conspiracy that deposed Peter on July 9 and brought his murder on July 18. Al though new czarina Catherine II ended the alliance with Prussia, she did not resume Russia’s involvement in the war, and without this Maria Theresa had no realistic hopes of holding Silesia.

Catherine ordered the return to Russia of General Count Zacharias Chernyshev’s corps sent by Peter to aid Frederick. Realizing the necessity for prompt action, Frederick convinced Chernyshev to postpone his departure for three days in order to influence Austrian marshal Daun’s decisions. Frederick then moved against Daun, entrenched at Burkersdorf.

The Russians and some Prussians to the northwest convinced Daun that the attack would come from that direction, while on July 21 Frederick and the bulk of the Prussian forces attacked from the northeast. Daun had perhaps 30,000 men at Burkersdorf, but Frederick enjoyed local superiority with perhaps 40,000, and that afternoon Daun withdrew. The Prussians suffered 1,600 casualties, while the Austrians lost at least that number dead or wounded and another 550 taken prisoner. The Russians then returned home. The battle, while not particularly bloody, was decisive in that Frederick now gradually regained control of Silesia.

Meanwhile on October 29, 1762, at Freiburg in Saxony, a 30,000-man Prussian army under Prince Henry defeated an Austrian, imperial, and Saxon army of 40,000 men under Austrian marshal Giovanni Serbelloni in the final major action of the war between Prussia and Austria. In the west, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, commanding more than 12,000 allied troops and 70 siege guns, captured Kassel (Cassel) in Hesse on October 12, taking 5,300 Frenchmen prisoner, and in November he drove French forces back across the Rhine.

The Seven Years’ War also saw major fighting overseas. Here the British capitalized on their control of the seas. Fighting in America, which had begun earlier and was known as the French and Indian War (1754-1763), saw the English conquer New France and also secure Florida from Spain. (On November 13, 1762, in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, French king Louis XV compensated King Charles III of Spain by secretly ceding to Spain all Louisiana west of the Mississippi, including New Orleans.) In the Third Carnatic War (1757-1763) the British cemented their position in India against the French.

The British also triumphed in the Caribbean. In a bid to acquire some of the rich French sugar islands, the British invaded Martinique in January 1759. Re buffed here by a sizable French garrison, the British moved against Guadeloupe instead. Landing there on January 23, the British captured it on May 1. The British returned to Martinique in January 1762 with a large force, and this last French stronghold in the West Indies surrendered on February 12. The British also captured St. Lucia (February 25) and Grenada (March 4).

Following Spain’s entry into the war on the side of France, British forces moved against Cuba. Admiral Sir George Pocock commanded an armada of some 200 ships carrying 15,500 ground troops, many of them provincials, under Lieutenant General George Keppel, Earl of Albemarle. The troops landed near Havana beginning on June 7, 1762, and following a siege, Havana surrendered on August 13. The British secured some £3 million in specie and important stores as well as 9 Spanish ships of the line. British casualties totaled 1,790 killed, wounded, or missing, but many others fell prey to disease.

British forces also moved against the Philippines. On September 23, 1762, a British expeditionary force of some 2,300 men under Brigadier General Draper lifted by the ships of Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Cornish’s East India Squadron and two East Indiamen arrived in the Philippines, much to the surprise of the Spanish. On October 5, Spanish authorities surrendered not only Manila but also the entire Philip pine Islands. Manila was to be ransomed for 4 million Spanish dollars, although only half this sum was ever paid. The Philippines and the prize money were handed over to the East India Company. In all, the operation cost the British 150 casualties.

All participating states were now thoroughly exhausted by the fighting, and serious peace talks began in November 1762. In the Treaty of Paris of February 10, 1763, Britain, France, and Spain concluded peace. France ceded to Britain both New France and Cape Breton Island; both sides recognized the Mississippi River as the boundary between the British colonies and French Louisiana (secretly ceded to Spain). France also ceded to Britain Grenada in the West Indies and its possessions on the Senegal River in Africa.

One of the biggest issues of the peace was whether Britain should retain the rich sugar island of Guadeloupe or New France (Canada). There were strong voices in Britain for Guadeloupe, which offered the promise of helping to offset the tremendous financial cost of the war. Besides, it might be wise to keep the French threat to ensure the loyalty of the North American English colonists. In the end, however, London kept Canada and returned Guadeloupe, with tremendous consequences for American history. France regained Martinique, Goree in Africa, and the island of Belle-Isle off the French coast. France also regained Pondicherry and Chandernagor in India, but the British were now clearly dominant there. Spain lost Florida to Britain, but Britain returned to the Spanish its conquests in Cuba, including Havana, as well as the Philippines.

On February 15, 1763, Austria, Prussia, and Saxony concluded peace in the Treaty of Hubertusburg. It reconfirmed the previous treaties of Breslau, Berlin, and Dresden in that Prussia kept possession of Silesia. Saxony was restored, and all three nations retained their antebellum boundaries. Prussia agreed to support Archduke Joseph (the future Joseph II) as Holy Roman emperor.

Significance

Prussia emerged from the war with its prestige much enhanced and confirmed as a major European power, although the rivalry with Austria remained. Internationally, Britain was clearly the world’s chief colonial power. France and Spain had been humiliated, and French leaders yearned for revenge, the opportunity for which came during the American Revolutionary War.

Further Reading Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of the Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. Black, Jeremy. Pitt the Elder: The Great Commoner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Clowes, William Laird. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Vol. 3, 1898. Reprint ed. London: Chatham, 1996. Corbett, Julian S. England in the Seven Years’ War. London: Greenhill Books, 1992. Dull, Jonathan. The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery. New York: Penguin, 1976. Middleton, Richard. The Bells of Victory: The Pitt-Newcastle Ministry and the Conduct of the Seven Years’ War, 1757-1762. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763)

Who won the seven years war?

Great Britain won the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). The Treaty of Paris (1973) gave Great Britain territorial gains in North America, including all French territory east of the Mississippi, as well as Florida, and returned Cuba to Spain.

What was the seven years war?

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) started on May 17th, 1756 and ended on February 15th, 1763, lasting a total of 6 years, 8 months, 4 weeks and 1 day.

When did the seven years war start?

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) started on May 17th, 1756 and lasted a total of 6 years, 8 months, 4 weeks and 1 day.

When did the seven years war end?

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) ended on February 15th, 1763 and lasted a total of 6 years, 8 months, 4 weeks and 1 day.