The Etruscan Inheritance

When Rome appeared as a city-state in the Tiber valley some

time in the middle of the eighth century bce, its first army differed little

from those of other small communities in Latium. It is believed Rome’s first

military organization was based on the tribal system, reflecting the three

original Roman tribes (the Ramnes, the Tities, and the Luceres). Each tribe

provided 1,000 infantry towards the army, made up of ten centuries consisting

of 100 men. The tribal contingent was under the command of a tribunus or tribal

officer. Together, these 3,000 men made up a legio or levy. This infantry force

was supplemented by a small body of 300 equites or ‘knights’, aristocratic

cavalry drawn equally from the three tribes.

Initially, the organization of the early Roman army was

heavily influenced by their powerful neighbours to the north, the Etruscans.

Etruscan civilization emerged in Etruria around 900 bce as a confederation of

city-states. By 650 they had expanded in central Italy and become the dominant

cultural and economic force in the region, trading widely with Greeks and

Phoenicians on the peninsula. Under direct occupation by the Etruscans between

c.625 and 509, Rome benefited greatly from this cultural exchange, with Roman

villages transformed into a thriving city-state. As in ancient Sumeria and

archaic Greece, each Etruscan city raised its own army. And although these

cities were united in a league of usually twelve cities, they seldom operated

together unless faced with an outside threat. Like the Greek poleis to the

east, the Etruscan city-states spent most of their energy fighting each other.

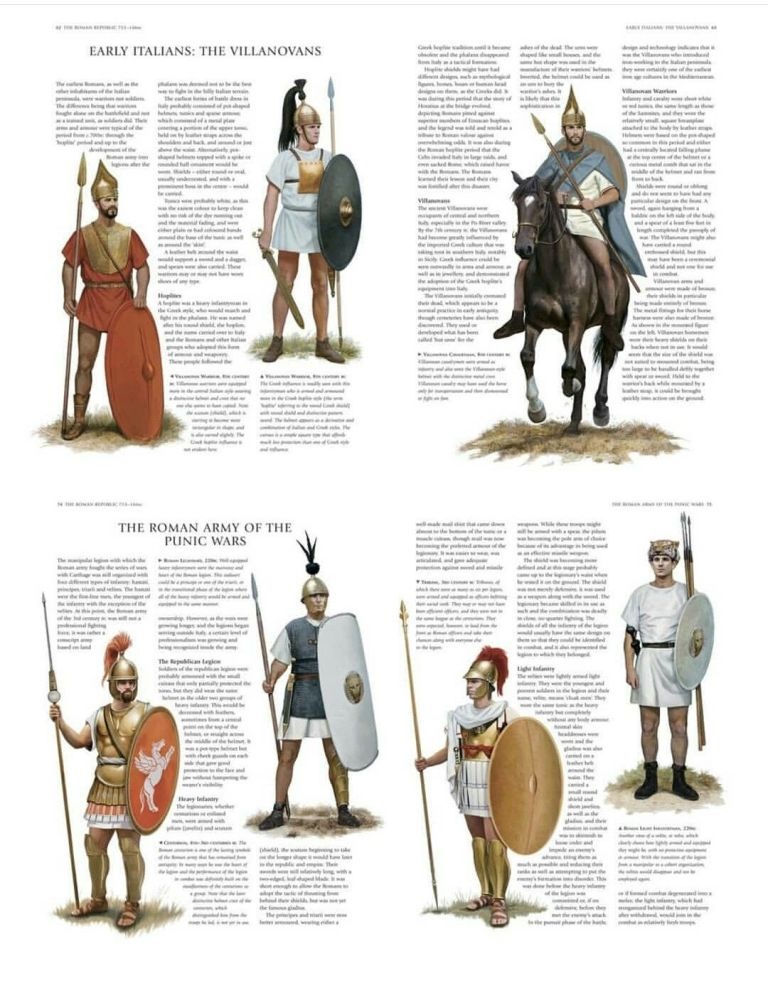

Some time in the sixth century bce, the Etruscans adopted

the Greek method of fighting and organized their militia-armies into phalanxes.

After conquering the Roman city-state in the late sixth century bce, the newly

created Etrusco-Roman army was composed of two parts: the Etruscans and their

subjects the Romans and Latins. The Etruscans fought in the centre as heavy

infantry hoplites, while the Romans and Latins fought in their native style

with spears, axes and javelins on either wing. The army was divided into five classes

depending on nationality. The largest contingent, or first class, was composed

of Etruscan heavy infantry armed in Greek fashion with heavy thrusting spear

and long sword, and protected by breastplate, helmet, greaves and a heavy round

shield. The second class contained spearmen conscripted from subject peoples

and armed in Italian fashion with spear, sword, helmet, greaves and the oval

Italic shield or scutum. The third class was lightly armoured heavy infantry

spearmen with scutum, while the fourth and fifth classes were light infantry

javelineers and slingers.

The second of the Etruscan overlords in Rome, Servius

Tullius, is credited in the middle of the sixth century bce with attempting to

integrate the population by reorganizing the army according to wealth and not

nationality. The Servian reforms reflected an old Indo-European custom where

citizenship depended on property and the ability to maintain a panoply and

serve in the militia. The reforms divided Etrusco-Roman society into seven

groups. The wealthiest group formed the cavalry or equites, made up of Etruscan

nobles and members of the Roman patrician class. The equites did not act in the

capacity of heavy or light cavalry, but served as mounted infantry and

reconnaissance.

The second wealthiest group acted as heavy infantry,

fighting in the phalangeal formation and armed as before in the Greek manner.

The third to sixth groups were armed in native Italian fashion identical to the

pre-Servian period. The seventh class, or capite censi, were too poor to

qualify for military service. Tactically, the Servian army fought as before,

with heavy infantry in the centre phalanx, protected by lightly armoured heavy

infantry on the wings and light infantry skirmishers in the front until the

phalanx engaged. There is no mention of archers in the Servian reforms. Like

the Greeks, the Romans seemed to disdain the bow and arrow as a weapon of war,

preferring it for hunting.

The Early Roman Republican Army

In 509 bce the Romans overthrew Etruscan rule. Newly independent

Rome replaced the Etruscan monarchy with a republic governed by a council of

elders drawn from the wealthy patrician class. This council, or Senate,

annually elected two consuls as chief magistrates of the Roman state. From 362

imperium, or the authority to command the Roman army, was entrusted to the

consuls, or to their junior colleagues, the praetors. Though the election of

co-rulers ensured a balance of political power, it had serious military

drawbacks. The two consuls shared responsibilities for military operations,

alternating command privileges every other day. Recognizing the inefficiency of

this system, Roman law provided for the appointment of a dictator in times of

national crisis for the duration of six months.

The early republican army was a citizen army. In fact, the

original meaning for the word legion (derived from legere, Latin for ‘to gather

together’) was a draft or levy of heavy infantry drawn from the property-owning

citizen-farmers living around Rome. The army continued to adhere

organizationally to the Servian reforms and consisted of three legions, each of

1,000 men, supplemented by light infantry provided by the poorer citizens and

cavalry by the wealthy patrician class. Divided into ten centuries of 100 men,

each legion was commanded by a tribune appointed from the patrician class,

while each century was commanded by a centurion promoted or elected from the

ranks of the legionaries. By the first century bce, legions were organized

around a battlefield standard bearing an eagle, below which was inscribed the

legion’s roman numeral and the letters ‘SPQR’ (Senatus Populusque Romanus),

representing ‘both the sovereign Roman people and the advisory Senate which

guided its actions’. And though the number of legions varied depending on the

period, the importance of the legionary eagle as a visible sign of duty, honour

and patriotism for generations of Roman soldiers remained constant for hundreds

of years, even surviving Rome’s transition from republic to empire.

Nothing brought more dishonour to a Roman commander and his

legion than losing their eagle in combat, and emperors would go to great

lengths to get them back if lost. Caesar tells us that when his legionaries

hesitated while landing in Britain in 55 bce, the aquilifer (eagle-standard-bearer)

for the X Legion jumped into the waves and waded toward the half-naked,

frenzied Britons. Fearing their eagle standard would be captured, the other

legionaries flung themselves into the water and attacked the enemy. Rome’s

first emperor, Octavian Augustus (r. 31 bce–14 ce), spent large sums of money

recovering the eagle standards lost by the Roman general Marcus Licinius

Crassus to the Parthians fifty years earlier at the battle of Carrhae in 53

bce. And when the elderly Augustus lost three legions and subsequently three

eagles in the battle of Teutoburg in 9 ce, he is said to have wandered his

palace muttering ‘Quintili Vare, legiones redde’ (‘Quintilius Varus, give me

back my legions’).

During the first century of republican rule, the Roman army

continued to utilize the phalanx-based tactical system. But the battle square

proved less effective against opponents unaccustomed to the stylized hoplite

warfare favoured by the Mediterranean classical civilizations. When, in 390

bce, 30,000 Gauls crossed the Apennines in search of plunder, the defending

Roman legions were pushed against the Allia River. The Gauls, or Celts as they

were also called, were an Indo-European people who inhabited an area of western

Europe including modern Britain, the southern Netherlands, Switzerland and

Germany west of the Rhine. Most of the Gauls were semi-nomadic (influenced by

contacts with Greeks and Romans), organized into tribes and capable of fielding

very large armies. The Roman phalanxes, outnumbered two to one and overwhelmed

by the ferocity and physical size of the Celtic marauders, were defeated,

unable to cope with the barbarians’ open formation and oblique attacks. The

sack of the ‘Eternal City’ in 390 left a lasting impression on the psyche of

Roman civilization. The surviving Romans who witnessed the violation of their

city from a nearby hill vowed never again to fight unprepared.

The Camillan Reforms and the Invention of the Maniple

Legion

After the sack of Rome by the Gauls in 390, the pragmatism

which is associated with Roman civilization as a whole was applied to warfare,

with Roman commanders altering the panoply and tactical formation of the

legions to meet the different fighting styles of their opponents, whether

barbarian or civilized. The military reforms of the early fourth century are

associated with the leader Marcus Furius Camillus, a man credited with saving

the city from the Gauls and remembered as a second founder of Rome. Although

history cannot precisely answer if Camillus himself was responsible for the

reforms, the changes that bear his name dramatically altered the character of

the Roman legion in the fourth century.

As the Roman state grew at the expense of its neighbours in

northern and central Italy, the Roman army expanded from three to four legions,

and the number of legionaries per legion grew to perhaps 4,000 infantry. By 350

the centuries had been reduced from 100 to between 60 and 80 men apiece, and

the centuries in each legion were divided among 10 cohorts for administrative

reasons. The Roman army’s experience against Gauls in the north and campaigns

against the Samnites (343–290) in the rough, hilly terrain of central Italy

forced a change in tactical organization, one which gave individual legionaries

more responsibility and greater tactical freedom.

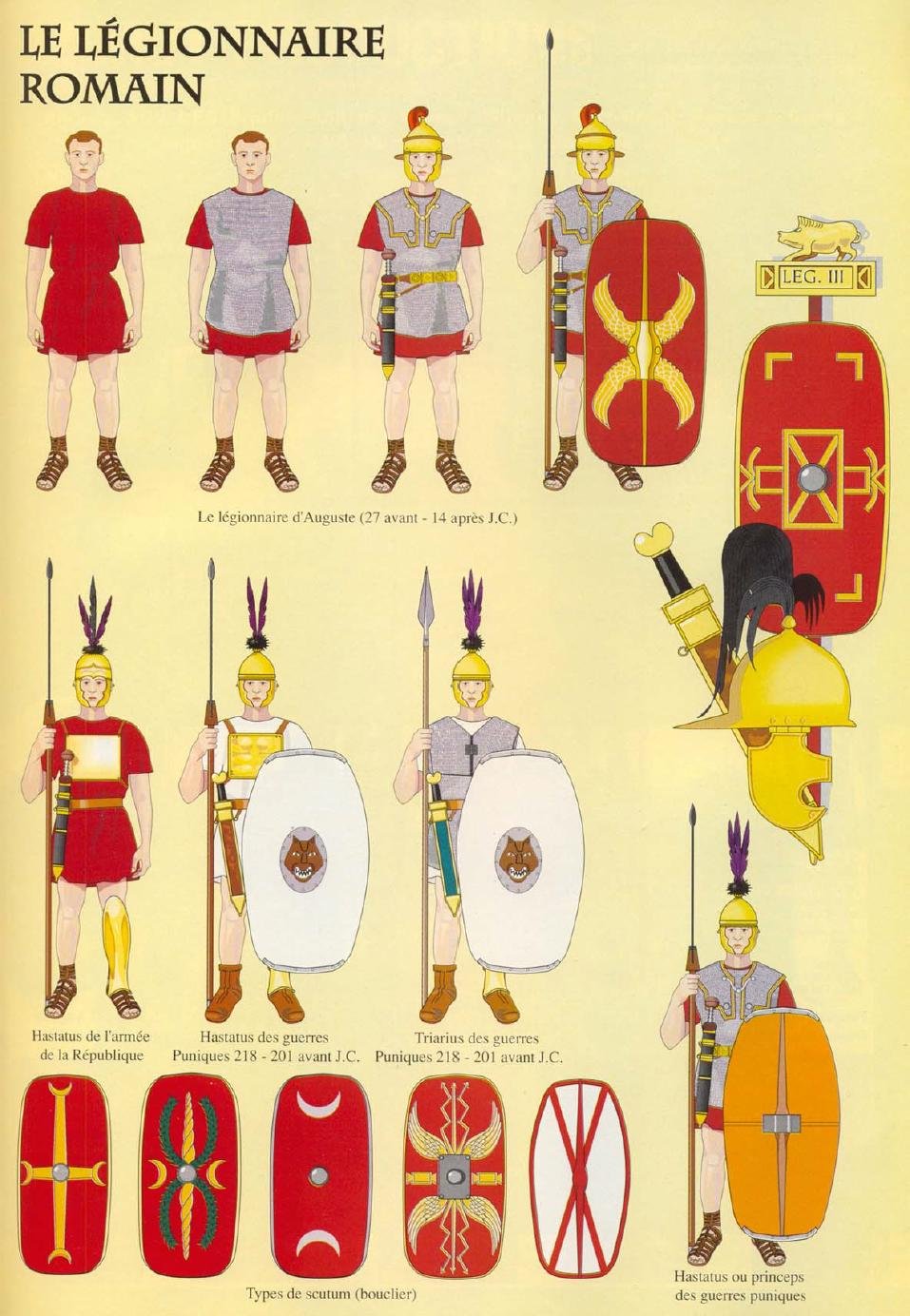

In order to achieve maximum tactical flexibility, the Roman

army abandoned the phalanx altogether in favour of the most well-articulated

tactical formation of the pre-modern world. This flexible linear formation

consisted of four classes of soldiers defined not only by wealth, but also by

age and experience. The Greek-styled battle square was replaced by three lines

of heavy infantry, the first two-thirds armed in an innovative manner with two

weighted javelins, or pila, and a sword, and protected by helmet, breastplate,

greaves and the traditional oval scutum favoured by the lower classes. The

ranks of the forward of these two lines or hastati were filled with young adult

males in their twenties, while the centre formation, or principes, comprised

veterans in their thirties. The third and last line or triarii were armoured as

above but for the old-style thrusting spear and scutum. The triarii consisted

of the oldest veterans and acted as a reserve. The poorest and youngest men

served as velites or light infantry skirmishers. Armed with light javelins and

sword, and unprotected except for helmet and hide-covered wicker shield, the

velites acted as a screen for their heavier armed and less mobile comrades.

Each legionary was still responsible for supplying his own panoply, but in

order to maintain uniformity within each century, the weapons were frequently

purchased from the state.

Before battle, the hastati, principes and triarii formed up

in homogeneous rectangular units or maniples of 120–160 men (two centuries

probably deployed side by side), protected by the light infantry velites. Each

maniple organized around a signum or standard kept by the signifer, who led the

way on the march and in combat. Each maniple deployed as a small independent

unit, typically with a twenty-man front and four-man depth, and may have been

separated from its lateral neighbour by the width of its own frontage, though

this is still a matter of some debate. Livy tells us that the maniples were ‘a

small distance apart’. Moreover, the maniples of hastati, principes and triarii

were staggered, with the principes covering the gaps of the hastati in front,

and the triarii covering the gaps of the principes. This chequerboard formation

or quincunx provided maximum tactical flexibility for the maniple, allowing it

to deliver or meet an attack from any direction.

In battle the maniple legion presented a double threat to

its adversaries. After the screening velites withdrew through the ranks of the

heavy infantry, the hastati moved forward and threw their light pila at 35

yards, quickly followed by their heavy pila. Drawing their short thrusting

Spanish swords or gladii, the front ranks of the hastati charged their enemy,

whose ranks were presumably broken up by the javelin discharge. As the Roman

heavy infantry thrust into the enemy, the succeeding hastati threw their pila

and engaged with swords. The battle became a series of furious combats with

both sides periodically drawing apart to recover. When the two formations joined,

the legionaries exploited the tears and stepped inside the spears of the first

rank into the densely packed mass, and wielded their swords with much greater

speed and control than the closely packed spearmen could defend against.

During one of these pauses, the hastati retreated through

the open ranks of the battle-tested and fresh principes and triarii. Meanwhile,

the principes then closed ranks and moved forward, discharging their pila and

engaging with swords in the manner of their younger comrades. If there was a

breach in the Roman line, the veteran triarii acted as true heavy infantry and

moved forward to fill the tear with their spears.

The new Roman system had many strengths. By merging heavy

and light infantry into the pilum-carrying legionary, the Roman army gave its

soldiers the ability to break up the enemy formation with missile fire just

moments before weighing into them with sword and shield, in effect merging

heavy and light infantry into one weapon system. Once engaged, the maniple’s relatively

open formation emphasized individual prowess, and gave each legionary the

responsibility of defending approximately 36 square feet between himself and

his fellow legionaries, a fact which placed special emphasis on swordplay in

training exercises. But even if the maniple failed, it could be replaced by a

fresh one in the rear. This ability to rotate fatigued legionaries with fresh

soldiers gave the Romans a powerful advantage over their enemies.

The Tarentine and Punic Wars

The Camillan military reorganization would serve the

republic well in its expansion against the Samnites, Etruscans and Gauls in

northern and central Italy during the fourth century bce. But Rome would face

new challenges in the third century from the Greeks in southern Italy, the

Carthaginians in Spain and north Africa, and Alexander’s successor states in

the Levant. Rome’s martial contacts with these other regional powers would test

the effectiveness of the maniple legion against combined-arms tactical systems

inspired by the success of the Macedonian art of war.

The first significant test of the maniple legion came

against the Greeks in southern Italy in the Tarentine Wars (281–267 bce).

Rome’s expansion into the lower peninsula forced the Greeks living there to

forge an alliance with King Pyrrhus (319–272), a brilliant general from the

Hellenized region of Epirus, north-west of Greece in what is now roughly modern

Albania. Rome’s struggle against Pyrrhus proved to be a difficult one, and over

the course of the war Rome suffered two major defeats. But poor generalship,

rather than an inferior fighting force, was the cause of the failures at

Heraclae and Asculum in 279. But even while Pyrrhus’ forces were victorious

over the Romans, his battles, especially at Heraclae, cost him dearly, giving

modern historians the term ‘pyrrhic victory’ to symbolize a costly victory. The

Romans finally decisively defeated Pyrrhus’ army at Beneventum in 275, and by

265 southern Italy was under Roman hegemony.

Perhaps the greatest opponent faced by Rome during its

republican period was Carthage, a former Phoenician colony on the coast of

north Africa (modern Tunisia) that over time developed into a formidable

military and naval power. As Rome was conquering southern Italy, Carthage

(called Punis in Latin) was consolidating its power in the western

Mediterranean, controlling north Africa and venturing into the Iberian

peninsula, Corsica and, to Rome’s dismay, the island of Sicily.

The Carthaginian presence in Sicily went back for centuries,

with both Greek and Carthaginian colonists sharing the island. But after the

Roman victory in the Tarentine Wars, Rome found itself at odds with Carthage

over Sicily, an island Rome needed to feed its growing population. The

resulting First Punic War (264–241 bce) witnessed Rome taking to the sea in

order to meet the Carthaginian threat. Although the Romans did not have a

history as mariners, they adapted well to naval warfare, building larger

galleys than the Carthaginians and preferring grappling and boarding to traditional

ramming. In fact, the Romans developed the corvus, or crow: an 18 foot gangway

with a pointed spike under its outboard end. Pivoted from a mast by a topping

lift, the corvus was dropped into the adjacent ship, securing it in place as

legionaries crossed the plank and engaged in hand-to-hand combat with enemy

sailors. The application of the corvus in naval warfare allowed Rome to fight

as a land power at sea, evening the odds against an accomplished naval power.

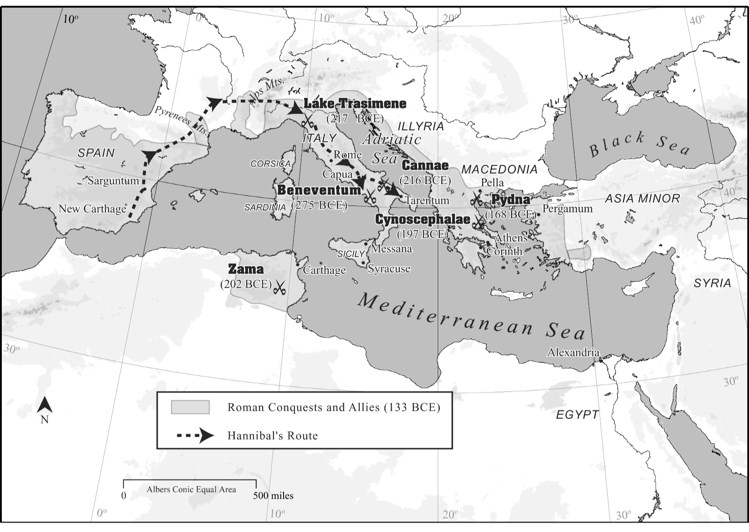

Roman Expansion in the Mediterranean, 3rd and 2nd

Centuries bce.

Although fierce storms destroyed large Roman fleets on two

separate occasions, Rome eventually forced an unequal peace on Carthage. Under

these terms, Carthage left Sicily under Roman hegemony and paid the Roman

Republic a war indemnity. But the peace lasted less than a generation, with

Rome and Carthage clashing over the fate of the city of Saguntum in eastern

Spain. In the Second Punic War (219–201) the Carthaginian commander in Spain,

Hannibal Barca (247–183), led an army of 40,000 troops and 37 elephants across

southern Gaul, over the Alps and into northern Italy. In order to avoid a

protracted war, Hannibal wanted to bring the conflict directly to Italy, defeat

the legions on the field of battle and force Rome to sue for peace.

Despite heavy losses to the rigours of the long march,

Hannibal defeated a Roman army at the battle of Trebia in 218. Here, Hannibal’s

19,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry crushed a Roman army of 36,000 infantry and

4,000 cavalry. His success convinced additional Gauls to join his army. The

following spring he defeated a second Roman army on the banks of Lake

Trasimene. Unwilling to risk another Roman army, the Senate elected Quintus

Fabius Maximus as dictator. Fabius Maximus refused to meet the Carthaginian

army in battle, preferring instead a strategy of delay and harassment. Rome’s

‘Fabian’ strategy forced Hannibal to keep moving in order not to exhaust local

food and forage. Unable to besiege Rome because of the absence of a siege

train, Hannibal crossed the Apennines and ravaged south-eastern Italy.

Unwilling to idly watch their country razed by an enemy

army, the newly elected consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius

Varro set out with an army consisting of sixteen legions to track down and

defeat Hannibal’s forces. In the summer of 216 the Romans caught up with

Hannibal near the village of Cannae in Apulia. The resulting battle of Cannae

pitted a Roman army of 80,000 infantry and 6,400 cavalry against Hannibal’s

allied army of 45,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry.

Hannibal camped west of the Aufidius River, while the Romans

camped two-thirds of their army opposite the invading army, the remainder

staying on the opposite side of the river to limit Carthaginian foraging.

Varro, whose day it was to command the Roman army, lined up for battle on the

east side of the river, placing his legionaries in the centre in an extra deep

formation (in places, between thirty-five and fifty men deep) because of the

narrowness of the plain. No more than 2,000 legionaries could engage the enemy

at one time. Moreover, many of the legionaries were fresh recruits recently

added to make up for the horrendous losses suffered at Trebia and Trasimene.

Varro’s strategy was simple: overwhelm the Carthaginian centre with the sheer

weight of his legionaries. Betting on his heavy infantry to win the day, he

then placed his inferior Roman cavalry on both wings to check the advance of

the more numerous Carthaginian horse.

Understanding the threat to his centre, Hannibal arranged

his troops south of the Romans, placing his infantry in the centre in a convex

formation and making the centre deeper than the flanks in order to match the

Roman frontage and delay the legions’ advance. Hannibal kept his African

infantry in reserve behind each flank of the crescent, and placed his cavalry

on the flanks opposite the Roman horsemen. Outnumbered two to one in total

numbers, the Carthaginian general placed his hope on his cavalry, which was

superior to the Romans’ in both numbers and quality.

As was typical of classical engagements, the battle opened

with skirmishing, then Varro ordered the weighted Roman centre to close with

the Carthaginians. At this moment Hannibal ordered the cavalry on his wings to

strike the weaker Roman cavalry opposite. As the Romans engaged with the

leading edge of the Carthaginian infantry, the centre yielded to the Roman

advance, slowly transforming from a convex to a concave formation. On the wings

the Carthaginian cavalry routed the Roman horse on both sides. As tens of

thousands of legionaries were sucked into the centre of this rapidly developing

killing field, Hannibal’s African heavy cavalry ran the Roman flank and swung

into the rear of the Roman army. Perhaps 60,000 Roman soldiers, including the

consul Paullus, were killed, and another 10,000 soldiers were taken prisoner as

a result of this classic double envelopment. So thorough was the Roman defeat

that never again did the Romans risk a large field army against Hannibal on

Italian soil.

The defeat at Cannae underlined the weakness of the Roman

heavy-infantry-based tactical system. At Trebia the legions managed to break

through the Carthaginian centre, shattering the cohesion of the enemy army. At

Cannae, the Romans massed their centre, determined to break through the

Spaniards and Celts forming the centre of Hannibal’s line. But this was the

tactic of a pike phalanx and a misuse of Roman swordsmen. By massing the

centre, the Romans were so tightly packed that they could not manoeuvre or

wield their short swords effectively, especially with rank upon rank pushing

from behind. The situation was further aggravated as the Romans, pushed from

behind, ‘tumbled’ over their own and enemy dead, further disrupting their

ranks. Hannibal’s men had no such problem as they gave way into a concave

formation.

In two years, Hannibal had killed or captured between 80,000

and 100,000 legionaries and their commanders, robbing Rome of a third of its

standing military force. Seemingly, the loss of three Roman armies in as many

years should have satisfied Hannibal’s plans for the defeat of Rome, but once

again the Roman Republic survived the deprivations of an enemy army in its

midst. Without a siege train, Hannibal could not capitalize on his battlefield

successes. Moreover, the strength of the Roman federation soon became apparent

when none of the key allied cities in Italy betrayed their capital on the

Tiber. They acted instead as islands of refuge for Roman armies between

disasters. Although able to march almost at will throughout the Italian

peninsula, Hannibal was incapable of bringing the Second Punic War to a

decisive conclusion, and time was on the Romans’ side.

Hannibal’s luck began to change in 207, when the relief army

from Spain of his younger brother Hasdrubal was intercepted and annihilated at

the Metaurus River. When news of the defeat and death of Hasdrubal reached the

Carthaginian army in southern Italy, many of Hannibal’s allies began to desert

him. Unable to defeat Hannibal in Italy, the Romans focused on fighting other

Carthaginian generals in Carthage’s sphere of influence. In 206 a Roman army

under the command of Scipio the Younger (c.236–184 bce) defeated the

Carthaginians in Spain, and two years later he landed at the head of a Roman

expeditionary force aimed at north Africa. In 203 Hannibal was recalled from

Italy in order to assemble a defence force for Carthage.

Hannibal and Scipio met at the decisive battle of Zama in

202, some 100 miles south-west of Carthage. For the first time, there was

relative parity in numbers between the combatants, but the quality of Roman

forces was superior to Hannibal’s army, and Scipio proved to be an experienced

general who understood the full tactical capabilities of the legion on the

battlefield. Scipio’s force was probably slightly inferior in infantry (he had 34,000

footmen against 36,000 Carthaginians), but was superior in cavalry after the

defection of the Numidians to his side, with 6,000 cavalry against Hannibal’s

4,000 horse and 80 elephants.

Hannibal arranged his infantry in three lines. He placed his

light troops and dead brother’s army in the front, hastily conscripted African

levy in the middle, and his veteran army from Italy in the rear. In the very

front of his infantry he placed his war elephants. Hannibal placed his cavalry

on the wings, putting his heavy horse on the right and light horse on the left.

Scipio arrayed his infantry and cavalry with his legionaries

in the centre and heavy cavalry on the left wing and light cavalry on the right

wing. But instead of forming up his legions in the quincunx formation as was

standard practice, Scipio arranged the maniples of hastati, principes and

triarii directly behind and in front of one another, forming lanes through the

ranks of soldiers. Scipio was careful to arrange his legions in this unorthodox

manner under a screen of light infantry velites. The plan worked very well.

When Hannibal initiated battle with a charge of elephants, most of them were

confused by the yelling and trumpet blasts from the legions, and stampeded

across the front of the armies and into their own cavalry. Those elephants that

successfully reached the Roman line were goaded and herded down the lanes by

velites, passing harmlessly to the rear of the legions.

Capitalizing on the confusion caused by rioting elephants

pushing into the Carthaginian wings, Scipio ordered his cavalry to charge,

pushing Hannibal’s horsemen from the field. Meanwhile, as the infantry closed,

Hannibal’s first line was forced back by the pilum discharge and shock combat

of the engaging hastati. But the African conscripts in the second line refused

to admit the retreating first line, infuriating the allied Celts and Ligurians

who forced their own centre or streamed around the flanks. The second line then

cracked, pushing back into Hannibal’s veteran third line who, like the second

line, refused to let any of their retreating comrades pass through their ranks.

Perhaps fearing an overextension or outflanking, Scipio ordered a recall of his

legions.

The break in the battle allowed both sides to reform.

Hannibal brought his fresh veteran infantry forward in a single line, then

extended their frontage. Scipio ordered his principes and triarii to the wings

to counter this move, keeping his tired hastati in the centre. But Scipio,

faced with a corps of veterans who had served with Hannibal in Italy for a

decade and a half, did not hesitate in sending his army again into the fray. As

the infantry clashed, the Roman and Numidian cavalry returned to the

battlefield and charged the Carthaginian rear. Though Hannibal escaped, the

Carthaginian losses exceeded 20,000 dead and perhaps 20,000 prisoners. Scipio

lost 1,500 legionaries and perhaps 3,000 allied cavalry. Hannibal returned to

Carthage and advised his government to sue for peace.

Carthage was never again a regional power after the Second

Punic War, though Roman fears of a Carthaginian revival precipitated a Third

Punic War (149–146 bce). The result of the conflict was the razing of Carthage

and the division of its territories between Numidia and the Roman province of

‘Africa’. Scipio, dubbed ‘Africanus’ because of his victory at Zama, emerged as

a leading statesman, while Hannibal found military appointments under various

rulers in the Hellenistic East, committing suicide in 183 bce in order to avoid

being betrayed into Roman hands.

Legion versus Phalanx: The Macedonian Wars

Rome’s war with Hannibal brought the Italian power into

direct conflict with King Philip V of Macedon (238–179 bce), one of Alexander’s

successors in the east, initiating a series of wars that eventually pulled Rome

into the gravity of Hellenistic politics. The appeal of Rhodes and Pergamum for

a Roman ally against the threat of an alliance between Philip V and Antiochus

III of Syria piqued the Senate’s interest in the region, initiating a series of

conflicts in Greece known as the Four Macedonian Wars (216–146 bce).

Tactically, these wars demonstrated the superiority of the maniple legion over

the fully evolved phalanx. Ever since the days of Camillus when the maniple

formation was first introduced, the Roman legion, unlike the

Macedonian-inspired phalanx, had developed consistently in the direction of

flexibility. When these two tactical systems met on the battlefield, the result

of the confrontation was usually catastrophic for the Greeks because of the vastly

different capabilities of the weapon systems employed.

The historian Livy explained the psychological effects of

Philip V’s first encountered with Roman infantry. In 200 bce, the Romans came

to support their Athenian allies against the Macedonians. Philip’s cavalry

engaged the Romans the day before and, normal to Greek warfare, the fallen were

to be buried with full honours as a sort of pep rally for the coming

engagement. Philip soon wished he had not agreed to the ceremony, for his

soldiers were not prepared for what they saw: ‘When they had seen bodies

chopped to pieces by the Spanish sword, arms torn away, shoulders and all, or

heads separated from bodies … or vitals laid open … they realized in a

general panic with what weapons and what men, they had to fight.’

The Greeks, used to the neat puncture wounds inflicted by

javelins and pikes, were visibly shaken by the wound signature of the short

Spanish sword or gladius. The gladius was slightly less than 2 feet long with a

double-edged blade 3 inches in width, adopted from the short thrusting sword

used on the Iberian peninsula. Slight modifications would transform this

superior thrusting sword into a deadly cleaving instrument. The gladius was,

according to one historian, ‘the most deadly of all weapons produced by ancient

armies, and it killed more soldiers than any other weapon in history until the

invention of the gun’. The gladius would be used to good effect by the Roman

legionary against the sarissa-wielding phalanxes.

Three years later, at the battle of Cynoscephalae in 197

bce, Philip V was defeated by the Roman commander Titus Quinctius Flaminius in

a confrontation that illustrated the superior tactical flexibility of the

maniple legion. The opposing armies were almost equal in number. The Roman army

consisting of 26,000 footmen (18,000 legionaries and 8,000 allied phalangeal

infantry from the Athenian-led Aetolian League), 2,000 cavalry and 20

elephants. The Macedonians fielded an army of 25,500 infantry and 2,000

cavalry. The battle began as light infantry skirmishers met in the mists

surrounding the Cynoscephalae hills in Thessaly. Initially, the Roman light

infantry enjoyed the upper hand until Philip’s cavalry arrived, forcing the

Romans to make an orderly retreat.

Seizing the high uneven ground along the ridge, the

Macedonians deployed their heavy infantry phalanxes on the left wing and in the

centre, then placed their cavalry on the more even ground on the right.

Flaminius split his two heavy infantry legions between the centre and the right

wing, with the right wing further reinforced with the Greek phalanx and a

detachment of heavy cavalry and all twenty elephants. On the left wing,

Flaminius placed the remainder of his heavy cavalry across from the Macedonian

horse.

Philip began the battle with a downhill infantry and cavalry

charge, forcing the Roman centre and left wing back. But his attack was

probably premature, because it took place before his own left wing was fully

deployed. Seeing this opportunity, Flaminius ordered his right plus his

elephants to attack the echeloned Macedonian left, easily pushing back the

still-forming phalanxes. On both sides the right wing was victorious, but an

unnamed tribune tipped the scales in Rome’s favour when he peeled off twenty

maniples from the Roman right and hit Philip’s centre in the rear, slaughtering

the exposed phalangites. The Macedonians, in retreat, raised their sarissas in

surrender, but the uncomprehending Romans cut them down. In all, Philip lost

8,000 men, while Flaminius’ losses were 700 dead.

The last great stand of the traditional phalangite army

against the Romans occurred at the battle of Pydna in 168 bce against Philip

V’s son Perseus. In the battle, despite being outnumbered, a Roman army

inflicted a crushing defeat on the Macedonian army. By 130 bce, Rome had

established hegemony over Greece, Macedon, and much of Asia Minor, and in the

west, Rome conquered southern Gaul and most of north Africa before 100 bce. The

reputation of Rome’s legions combined with adroit diplomacy was, at times,

sufficient to win territory. Rome conquered the entire Hellenistic east

virtually without fighting, relying instead on bluff and coercive diplomacy.

But when diplomacy did not work, the Roman army was capable of enforcing the

will of the Senate through organized violence, creating a new Mediterranean

empire in the process.

The Marian Reforms

At the end of the second century bce a number of changes in

the Roman army occurred that had great military, social and political

implications, some of which are associated with the consulships of Gaius Marius

(157–86 bce). On the military side, two of Marius’ reforms involved the

conversion of the cohort from an administrative to a tactical unit by making

the arms and equipment of the legion’s heavy infantry uniform, and by raising

the number of legionaries in each legion from around 4,000 to 5,000 men,

including support staff.

This modification in the legion’s equipment and formation

was due to the increasingly large tactical array of Rome’s Germanic enemies during

the second century bce. Consistent with Indo-European tradition, Germanic

infantry was organized into hundreds, a group of perhaps 100 warriors who swore

allegiance to a local chieftain. These formations often fought in what the

Romans called a cuneus (‘wedge’), sometimes referred to as a ‘boar’s head’

wedge. This battle array placed the heaviest armoured and best-armed men in the

front ranks, with lesser-armoured warriors filling in behind. This wedge

formation had limited offensive articulation, but presented plenty of impact

power on a small frontage. The boar’s head array was launched at an enemy in

order to break up opposing formations in a single movement. If the initial

attack miscarried before determined resistance, then the barbarians retreated

in disorder, but if the boar’s head was successful in breaking up the opposing

formation, then individual combat ensued, consistent with the Germanic fighting

ethos and the reality of unarticulated heavy infantry. Furthermore, barbarian

command capabilities were not sophisticated enough to be able to control more

than a single body of warriors. And though they sometimes used a second line of

troops, there is little evidence supporting the use of reserves.

Although the flexibility of the maniple proved adequate in

battle against the civilized armies of the Mediterranean basin, its limited

size of only two centuries did not allow it to meet the large Germanic battle

square on equal footing. The cohortal legion would meet this need. Marrying the

flexibility of the maniple to the mass of the phalanx, the cohortal legion

could meet the large Germanic battle squares yet retain the tactical mobility

that allowed it to deliver or meet an attack from any direction. Though it was

probably used in battle before his consulships, Marius used his considerable

political power to establish the cohortal legion as the standard legion. It

would remain virtually unchanged for the next 300 years. Marius is also

credited with making the eagle (aquila) the standard for the Roman legion.

The cohortal legion represented hundreds of years of

tactical evolution. Over the course of the early and middle republic, the Roman

legion was first provided with joints, then divided into echelons, then broken

up into maniples only to be finally reorganized again into large, compact

cohorts capable of great flexibility on the battlefield. This last evolution of

the legion was attainable only by the extraordinary discipline of the Roman

legionary, discipline that only increased as professionalism and length of

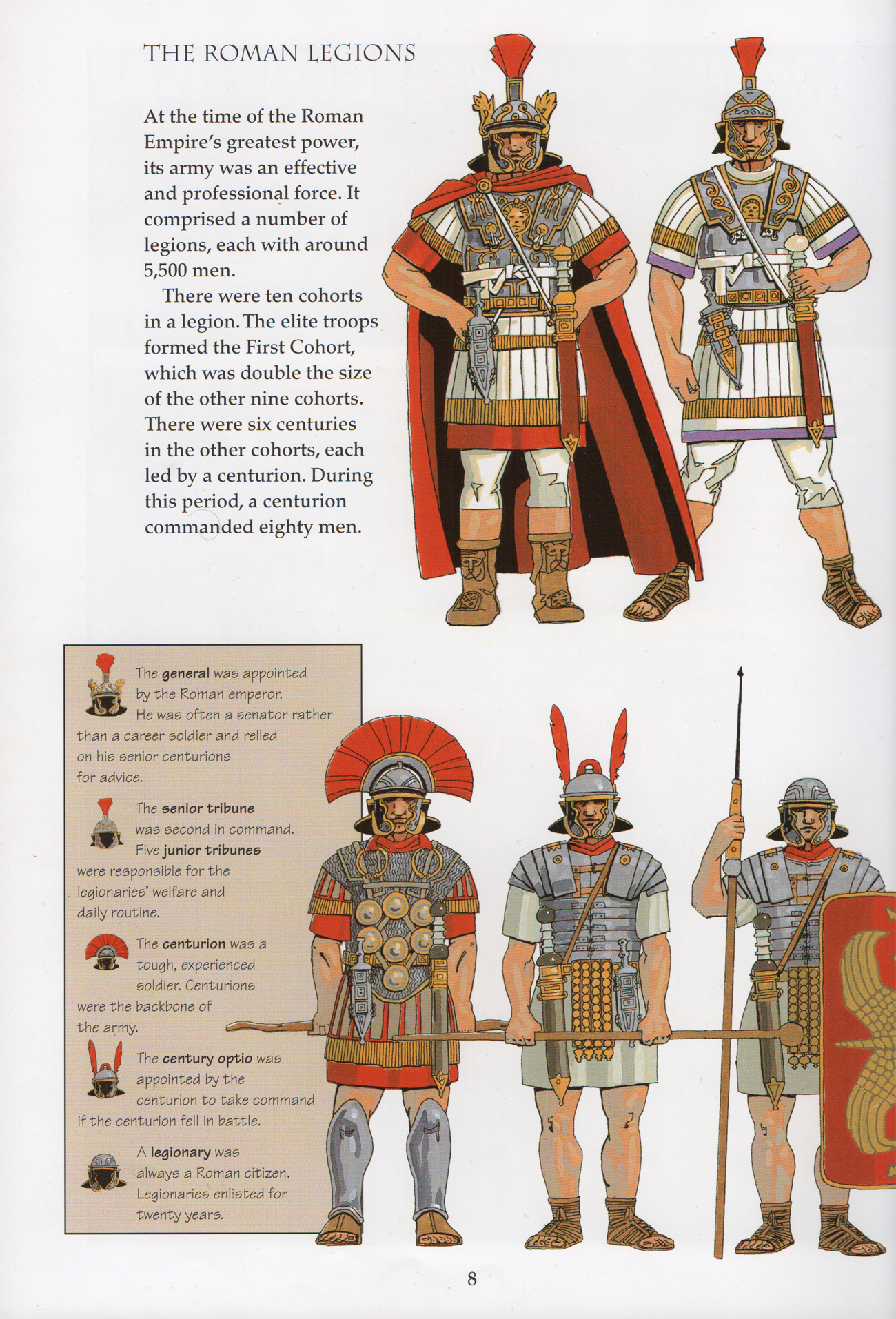

enlistment increased. The cohort legion was organized as follows:

8 men to a contubernium – 8 men

10 contubernia to a century – 80 men

2 centuries to a maniple – 160 men

3 maniples to a cohort – 480 men

10 cohorts to a legion – 4,800 men

Under the Marian reforms the light infantry velites were

abolished and became an allied responsibility fulfilled by auxiliaries. These

were troops of non-Italian origin, recruited from local allied tribes and

client kings. They employed the indigenous weapons of their nationality and

served the Romans in the role of light infantry and light cavalry. Julius

Caesar made extensive use of Gallic and, later, Germanic cavalry in his

conquest of Gaul, and these same troops proved effective against Pompeii during

the Civil War. Auxiliary units raised in the provinces by treaty obligations

were usually led by their own commanders, with successful battle captains

rewarded with Roman citizenship and titles. By the beginning of the Roman

Empire (31 bce–476 ce), auxiliaries were an indispensable complement to the

legion.

With the covering forces now the responsibility of allies,

the Romans concentrated solely on heavy infantry. Marius replaced the thrusting

spear of the third line triarii with the pilum and gladius carried by the

hastati and principes, creating a standardization of arms throughout the

legion. He also improved the pilum by replacing one of the two nails holding

the metal head to the wooden shaft with a wooden dowel. The pilum would break

on impact, ensuring that it could not be thrown back in combat. Defensively,

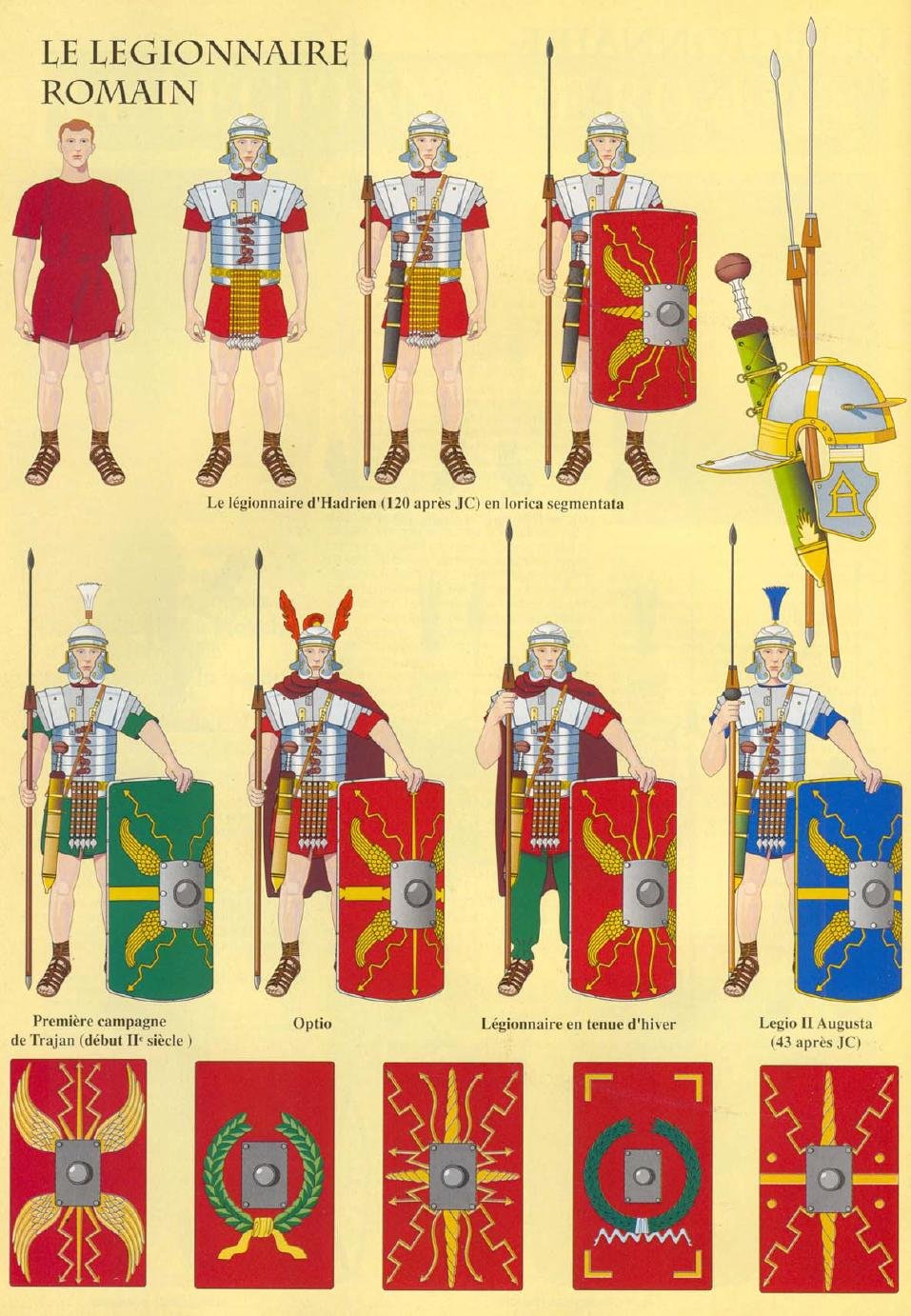

legionaries wore articulated banded armour known as lorica segmentata, which

gave them excellent protection and unprecedented mobility. The familiar

rectangular scutum also reached its final form about 100 bce.

Marius also improved the mobility of the Roman army by

allowing only one pack animal for every fifty men, requiring every legionary to

carry his own arms, armour, entrenching tools, personal items and several days’

rations on the march. Though his load might be 80 or 90 pounds, each of

‘Marius’ mules’ was capable of travelling up to 20 miles a day over good roads

and then fortifying the army camp as a precaution against nocturnal attack, a

standard Roman practice when in hostile territory. Furthermore, the Romans,

like the Persians, developed a very sophisticated highway system to support

their armies in the field. The Romans built 50,000 miles of paved roads and

200,000 miles of dirt roads linking the provinces, giving the legionaries

unprecedented strategic mobility.

The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (b. 37 ce) tells us in

his account of the Jewish revolt of 66–73 ce that when the Roman army was on

the march, it usually conformed to a standard configuration, one which remained

unchanged since the time of Polybius over 200 years before. Screening the

column and acting as forward scouts were contingents of lightly armed infantry

auxiliaries and cavalry, protecting the army from ambush. Next came the

vanguard, comprising one legion plus a force of cavalry. Because the duty was

dangerous, legions drew lots each day to determine which one should form the

vanguard. Behind the vanguard came the camp surveyors, made of ten men from

each century (or one man from each contubernium or tent). Their job was to

quickly mark out the camp at the end of the day. Behind the surveyors marched

the pioneer corps, engineers whose job it was to clear obstacles and bridge

rivers. Next came the commanding general’s personal baggage laagers, protected

by a strong mounted escort. In the middle of the column rode the general

himself, surrounded by a personal bodyguard drawn from the ranks of auxiliary

infantry and cavalry. Following the general were those cavalry alae organic to

each legion (made up of Roman cavalry regiments consisting of 120 horsemen per

legion). Next came the Roman siege train, men and mules pulling the dismantled

towers, rams and siege engines necessary to attack an enemy city. Senior

officers – legates, tribunes and auxiliary prefects with an escort of

handpicked troops – came next, followed by the legionaries themselves marching

six abreast. Each legion was headed by the aquilifer and followed by its own

baggage train controlled by each legion’s servants. Behind the legions followed

the rearguard, contingents of auxiliary heavy and light troops who fanned out

to protect the column from rear attack. Finally, camp followers would have been

found at the rear of the army, maintaining a close proximity for protection.

These followers normally would have included common-law wives, children,

prostitutes, merchants and slave dealers.

Frequently outnumbered on the battlefield and attacked from

many angles, the legion depended for its survival on following the direct

orders of the army commander. Battlefield victory and consistent performance

brought great opportunity for the legionary who, over time, could look forward

to promotion through the various ranks of centurion, which by the time of

Marius represented a whole class of officers. Moreover, the senior centurion of

a legion enjoyed considerable status, and the five senior centurions of each

legion were included in councils of war held by commanders of field armies. But

if the orders of a centurion were not followed and a century was judged

disobedient or cowardly in battle, the entire unit was subject to decimation.

One soldier in ten was selected by lot and beaten to death by his comrades,

enforcing an age-old adage that the key to battlefield success is the fear of

one’s own army over the fear of the enemy.

Finally, Marius dropped the property-owning qualifications

for military service, opening the ranks of the legion to the lowest social

class, the capite censi. Roman expansion in the third and second centuries bce

created a large slave class, and consolidation of small farms into vast

plantations or latifundia worked by foreign slaves eroded the class of farmer

which had always been the backbone of the Roman army. These displaced rural

Romans moved to the cities and became urban poor. Seeking a better life, many

of these young men enlisted for longer periods of service. Under Marius, length

of service was increased to six years, replacing the citizen-militia army of

the earlier republic with a professional army. But, perhaps most significantly,

in the unstable economic and political climate of the late republic, the

allegiance of the legionaries shifted from the Roman state to individual

generals, who provided their soldiers with status and booty during the

territorial expansion and civil wars of the first century bce .

The professionalization of the Roman army after the Marian

reforms led directly to the use and abuse of power by generals seeking to usurp

the power of the Senate. Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138–78 bce), one of Marius’

generals, marched on Rome with his legions and forced the Senate to name him

dictator in 82 bce. After conducting a reign of terror to wipe out all

opposition, Sulla restored the constitution and retired in 79, but his use of

military force against the government of Rome set a dangerous precedent. His

example of how an army could be used to seize power would prove most attractive

to ambitious men.

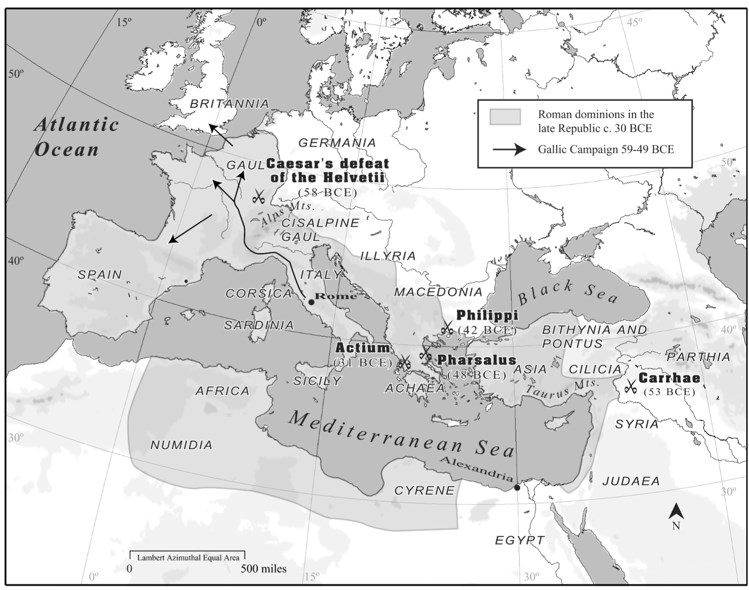

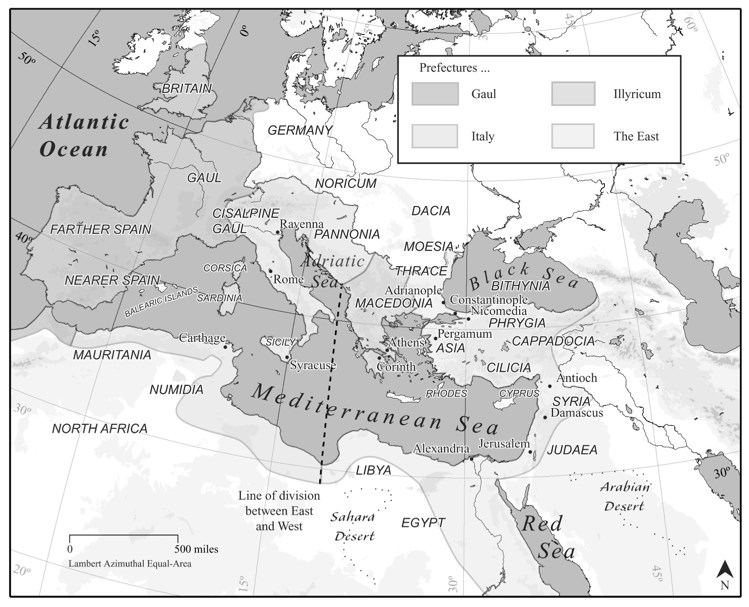

Roman Possessions in the Late Republic, 31 bce.

For the next fifty years, Roman history was characterized by

two important features: the jostling for power by a number of powerful

individuals and the civil wars generated by their conflicts. Not long after

Sulla retired, the Senate made two extraordinary military appointments that

raised to prominence two very strong personalities – Cnaeus Pompeius Magnus

(106–48 bce) and Marcus Licinius Crassus (c.112–53 bce). Pompey fought for

Sulla and was given military commands in Spain and the eastern Mediterranean,

returning to Rome as an accomplished military hero. Crassus had also fought for

Sulla, but, despite putting down Spartacus’ slave rebellion in 71 bce, he was

considered more of a statesman and businessman than military commander. In 61

bce, Julius Caesar joined Pompey and Crassus in a power-sharing arrangement

known as the First Triumvirate. Together, the combined wealth and political

power of these three men enabled them to dominate the Roman political scene.

The elder statesman Pompey had already proved his worth as a

military commander (earning a triumph while he was too young to even be a senator),

and Caesar and Crassus felt compelled to win an equally impressive reputation

on the battlefield. Caesar chose Gaul as his area of influence and brought the

Celts under direct Roman influence between 59 and 49 bce. Crassus, hungry for

military success to reinforce his political aspirations, set out for the east

with plans to invade Parthia.

The Cohortal Legion at War: The Gallic Campaigns

The last major territorial expansion under the republic took

place in Gaul between 59 and 49 bce. As proconsul (governor with imperium) of

Gaul, Gaius Julius Caesar (100–44 bce) commanded at various times between six

and eleven legions, and, counting auxiliaries (including Spanish, Gallic and

German horse), the strength of his army varied between 40,000 and 70,000 men.

Through many long and difficult military campaigns, Caesar used this army to

bring Transalpine Gaul (the area of Gaul north of the Alps) under Roman

hegemony.

Caesar’s military reputation as a great commander was made

against the semi-barbaric Gauls and the more aggressive Germanic tribes who

periodically invaded Roman Gaul. In his Gallic commentaries, a mostly

propagandistic work on his campaigns north of the Alps, Caesar tells us of an

unnamed battle in 58 bce in which perhaps 40,000 Roman soldiers and auxiliaries

faced an invasion of Gaul by perhaps 150,000 Celtic Helvetii and their Germanic

allies the Boii and Tulingi. Caesar intercepted the barbarian tribes as they

were attempting to migrate west from their homeland east of Lake Geneva across

central France. After a few successful ambushes of barbarian camps and the

slaughter of thousands of migrants on the spot, the Helvetii sent an ambassador

to sue for peace with the Roman general. When Caesar’s demand for damages and

hostages was refused, a decisive engagement was all but assured. The two armies

met at the southern edge of the rugged Morvan region in Burgundy.

According to Caesar’s account, on the day of the battle he

sent his cavalry to delay the enemy’s approach and withdrew the remainder of

his army to a nearby hill about 3 miles north-west of modern Toulon. He drew up

the four veteran legions in his army in three lines of six ranks each halfway

up the hill, and ordered his two recently levied legions and remaining

auxiliaries troops to the summit, quickly converting the hilltop into an

earthwork fortification and base camp. Caesar then ordered all of the officers’

horses taken to the summit so that no one could entertain the idea of retreat.

The Helvetii were the first to arrive before the Roman position and, without

waiting for reinforcements, attacked the Romans. The Romans used their

advantage in elevation to rain pila down on the Germans, stopping the enemy

advance in its tracks. Then the veteran legionaries drew their swords and

advanced down the hill. Though the Helvetii resisted, they were finally forced

to begin a slow fighting withdrawal toward a hill a mile away. Just as the

Helvetii gained the safety of the hill, warriors from the Boii and Tulingi

appeared on the right flank of the advancing Roman legions and threatened their

rear. Seeing the arrival of their allied tribes, the Helvetii once again

pressed forward.

Faced with a crisis, Caesar ordered his Romans to form a

double front, the first and second lines to oppose the Helvetii counter-attack,

and the third line to form a new front at an angle to the first in order to

face the newly arrived enemy. The battle, fought in two directions, continued

from early afternoon until evening, with Caesar recording in his commentaries

that not a single Gaul was seen running away. But finally, after suffering

perhaps 20,000 casualties, the Helvetii and their Germanic allies gave way

before the Roman advance, abandoning their camp and baggage, and taking flight

under the cover of night. Though Caesar gives no figures on Roman casualties in

this unnamed battle, he does state that the Roman army remained on the

battlefield for three days in order to bury their dead, treat the wounded and

rest before pursuing the Germans. This victory forced most of the survivors

back to their lands to act as a barrier against other barbarian tribes

attempting to cross the Rhine.

Legion versus Cavalry: The Battle of Carrhae

In the second century bce the Parthians carved out a

south-west Asian empire at the expense of the Seleucid kingdom, one of

Alexander’s successor states. As horse nomads from the Eurasian steppe, the

Parthians brought with them a strong equestrian tradition. The Parthian army

was a cavalry force, consisting of light cavalry horse archers supplemented by

noble lancers or cataphracts (from the Greek meaning ‘covered over’), chain- or

scale-mailed heavy cavalry whose ancestors reached back to the well-armoured

Persian cavalry of Cyrus the Great.

Parthian light cavalry wore little or no armour, instead

relying on mobility and ‘hit and run’ tactics. The standard Parthian horse

archer practice was to canter in loose order toward the infantry enemy. At 100

yards the formation broke into a gallop and fired arrows. At about 50 yards

(still out of range of most light infantry javelins), the formation wheeled

right and, still firing, rode along the front of the enemy formation.

Alternately, they reined in and skid-turned, then fired more arrows over their

shoulders as they retreated out of enemy archer range. This last manoeuvre

became known as the ‘Parthian shot’, although all Eurasian horse archers

practised it. These charges and volleys continued all day, with swarms of horse

archers darting in and out of dust clouds, and were designed to wear down

defending infantry squares. Moreover, the Parthians were masters of the ruse

and adept in the feigned retreat, pulling enemy cavalry into pursuit, then

ambushing them far from their camp.

Marcus Crassus was an experienced general, having served

under Sulla in the 80s and gained notoriety as the commander who finally put

down Spartacus’ revolt in 71 bce after it had defeated numerous Roman armies

and pillaged the Italian countryside. But defeating a slave revolt did not earn

him the most coveted reward in Rome – a triumphant parade. Instead, the Senate

awarded Crassus the governorship of Syria, and he intended to use this position

to push Roman hegemony east into Mesopotamia at the expense of the Parthians,

despite a peace treaty between the two empires. At sixty years of age, he

realized that this was his last chance to become the worthy heir of Pompey.

On his march toward the old Hellenistic capital at Seleucia

in Mesopotamia, Crassus occupied numerous Parthian frontier towns, provoking an

angry response from the Parthian king. The Roman army encountered the Parthian

host near Carrhae. Although many of the Romans wanted to rest there, Crassus,

urged by his son Publius, decided to march on. Publius was an aggressive

commander in search of a military reputation of his own who had served with

distinction under Julius Caesar in Gaul.

Unfortunately for the Romans, their slow moving,

infantry-based army soon attracted a Parthian force consisting of 1,000

cataphracts and some 8,000 horse archers, led by the capable Parthian general Surena.

Crassus, recognizing the unfavourable strategic situation evolving around his

army, formed up his troops into a battle square, placing his seven legions

(28,000 men), 4,000 light troops and 4,000 allied cavalry around his baggage

train as the Parthian horse archers surrounded and attacked the defending

Romans (Map 4.7(a)). According to Plutarch, the situation was dire:

The Parthians stood off from the Romans and began to

discharge their arrows at them from every direction, but they did not aim for accuracy

since the Roman formation was so continuous and dense that it was impossible to

miss. The impact of the arrows was tremendous since their bows were large and

powerful and the stiffness of the bow in drawing sent the missiles with great

force. At that point the Roman situation became grave, for if they remained in

formation they suffered wounds, and if they attempted to advance they still

were unable to accomplish anything, although they continued to suffer. For the

Parthians would flee while continuing to shoot at them and they are second to

this style of fighting only to the Scythians. It is the wisest of practices for

it allows you to defend yourself by fighting and removes the disgrace of

flight.

The Parthians continued to harass the Romans with their ‘hit

and run’ tactics, and were resupplied by camel with more arrows in order to

keep the pressure on.

Crassus tried to subdue the Parthian light cavalry with his

allied auxiliaries, but their numbers were insufficient to deal with the

mounted archers, and they were eventually forced back to the legionaries’

lines. Understanding that his army was slowly losing the battle of attrition,

Crassus sent forward his son Publius with eight cohorts, 500 archers and 1,300

cavalry, including a contingent of Gallic lancers (Map 4.7(b)). The Parthians

yielded to the Roman sally and Publius gave chase. But Publius’ forces were

surrounded by Parthian lancers and horse archers, and, separated from the Roman

main body, annihilated. Publius’ head was taken back to the Roman camp to taunt

Crassus. Night fell and the Parthians withdrew. Under cover of darkness, the

Romans retreated back to Carrhae, leaving behind an estimated 4,000 wounded,

who were butchered by the enemy the following morning. During the night,

another four cohorts lost contact with the main force and were cut down by the

Parthians.

Crassus and 500 of his cavalry made it back to Carrhae,

while the remainder of Crassus’ forces retreated to nearby mountains. But the

Romans in the mountains abandoned their strong position to aid Crassus.

Realizing that the Roman leader might escape, the Parthian commander, Surena, invited

Crassus to a parley, where he and his officers were killed. Total Roman losses

were 20,000 killed and perhaps 10,000 captured. Ten thousand Roman troops did

manage to escape to Roman territory. It was the worst Roman loss since Cannae.

Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae illustrated the danger of

bringing a poorly balanced combined-arms system into a hostile environment. The

Roman army entered the flat plain of Mesopotamia with insufficient cavalry and

light infantry. Unable to punish the Parthian light cavalry with their own

archers, the Roman legionaries were forced into defensive battle squares and

picked off by the enemy horse archers. The Parthian victory clearly

demonstrated the superiority of the light cavalry weapon system over heavy

infantry when campaigning on terrain that favoured horses. Although heavy

cavalry assisted the Parthian victory, the light cavalry horse archers could

have won the battle against poorly supported Roman heavy infantry unaided.

The Augustan Reforms

Octavian’s victory at the battle of Actium in 31 bce ended

nearly a century of turmoil and civil war. Taking the name Caesar Augustus (the

‘exalted one’), he understood that nothing had contributed more directly to the

failure of the republic than the growth of client armies and the inability of

the Senate to control their commanders. Augustus was determined that the same

fate would not befall his own regime. In order to stop this dangerous trend, he

set about designing a system under which the Roman army would be clearly

subordinate to him alone. To do this, he combined the title of Imperator

(originally reserved for commanders of victorious Roman armies) with the

consular powers of commander-in-chief, from which evolved the title ‘emperor’.

As both head of state and commander-in-chief, Augustus enjoyed a double hold

over provincial governors. He took further precautions by transferring these

governors at least once every four years, reserving the more sensitive commands

for his relatives, and personally controlling all important promotion, rewards

and pay rises in the army.

During Augustus’ reign, the Roman army was reduced from the

sixty legions left after Actium to 300,000 men in total, consisting of 150,000

Roman citizens in twenty-five legions and 150,000 non-citizens in auxiliary

infantry cohorts and cavalry regiments. For the next 200 years the number of

legions varied between twenty-five and thirty, not a large army for an empire

that contained nearly 60 million people. Under Augustus, the length of

enlistment changed dramatically, increasing from six to twenty years, with a

further five years required for veterans retained as officers. The reason for

this increased service was probably financial, because the pressure of

providing grants of land or money to discharged soldiers was very taxing to the

empire, so an extended enlistment was required to ease the economic burden.

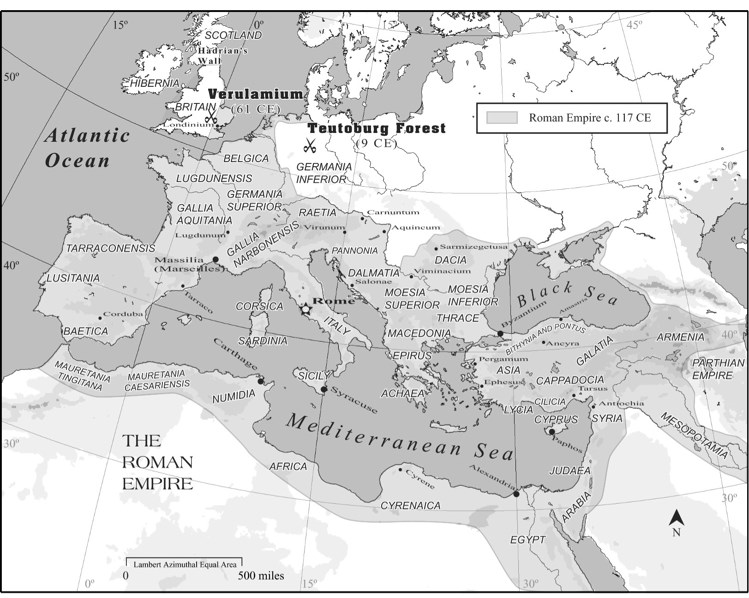

The Roman Empire under the Pax Romana.

Augustus did not modify the tactical organization instituted

by the Marian reforms. The Augustan legion still consisted of ten cohorts, but

some time in the middle of the first century ce, the strength of the first

cohort was doubled to five centuries of 160 men. Perhaps this was done to

provide the legion with a larger tactical formation when dealing with

barbarians, or as a tactical reserve. Augustus did, however, make a regiment,

or ala, of 120 cavalrymen organic to each legion. These men were drawn from the

ranks and mounted as scouts (exploratores) and messengers. The early Roman

cavalry was lightly armoured and capable of limited shock and missile action.

But the role of Roman cavalry on the battlefield increased because of prolonged

contacts with cavalry-based tactical systems in the east, and in the early

second century the Roman emperor Trajan raised an ala intended purely for shock

combat. Using the two-handed lance or kontos, these heavy cavalrymen could not

make effective use of a shield, so heavier armour was worn, modelled after the

Persian cataphracts. Called clibanarii, these lancers and mounts were protected

by composite chain- and scale-mail armour. As the empire wore on, clibanarii

formed an increasingly higher proportion of Roman cavalry and would become the

dominant tactical system of the later Byzantine Empire.

The role of the auxiliary also increased in importance in

the early imperial period, with the auxiliary’s organization and number

becoming standardized under Augustus. During the Civil Wars auxiliary units

varied in size and there was no set total of units authorized. Under Augustus,

the number of auxiliary troops rose to a number roughly equal to that of

legionary troops. Auxiliary cohorts and alae contained about 480–500 men, and

were called quingenaria, or ‘500 strong’. It was not until after the emperor

Nero (r. 54–68) that this number rose to 800–1,000 men, called cohortes

milliariae and alae milliariae (‘thousand strong’). In addition, an auxiliary

cohort made up of a mix of both infantry and cavalry units was created

(cohortes equitatae), with the proportion of these mixed units probably close to

four to one infantry to cavalry.

As the empire wore on, auxiliary units gained significant

influence within the Roman war machine’s command structure. Initially commanded

by their own chieftains, the Augustan reforms placed auxiliary troops under

Roman commanders. Over time, the value of the auxiliary on the battlefield

could be seen by the prestige associated with commanding these troops. The

title of tribunus was granted to the commander of the auxiliary cohors

milliaria, a title equal in seniority to that of a tribune of a legion.

Augustus also created a new imperial grand strategy, placing

Roman legions in a forward position on the frontiers, far away from Rome

itself. This grand strategy emphasized a fortified and guarded border or Limes,

placing the legions in perpetual contact with the barbarians and ensuring that

the Roman legionary was always in a high state of training and readiness. The

Limes system also helped keep the legions far from the Roman capital and away

from imperial politics.

To protect himself and ensure domestic tranquillity in Rome,

Augustus created a personal bodyguard called the Praetorian Guard consisting of

nine double-strength cohorts. The guardsmen were organized, trained and armed

like the regular legionaries, but were handpicked men of Italian origin who

were paid three times as much as normal Roman soldiers, and received benefits

after only sixteen years of service. The Praetorian Guard was the only fighting

force stationed in Italy. Augustus originally organized the guard so that only

three cohorts would be in Rome; the other six were to police the hinterland,

with rotation back to Rome each spring and autumn. But after Caesar Augustus’

death in 14 ce, this rotation fell apart and the majority of the guard stayed

at home, where they often participated in the selection of future emperors. In

fact, four of Rome’s emperors were elevated to the purple from the ranks of the

Praetorian Guard.

Further Roman expansion was blocked in the Near East by

Parthia, but Augustus used his legions to put down revolts in the Roman

provinces of Iberia and Illyria, and launched expeditions into Dacia (modern

Romania) and against German tribes east of the Rhine. Augustus’ campaign across

the Rhine ended in disaster when a Roman army consisting of three legions

ventured into northern Germany in 9 ce and was ambushed by a large force of

German tribesmen in the Teutoburg Forest. In this battle, the Roman heavy

infantry legionary would face a capable and determined Germanic foe utilizing

light infantry tactics.

Legion versus Light Infantry: The Battle of Teutoburg

Forest

In 6 ce Augustus sent Publius Quintilius Varus to keep the

peace in the newly occupied region of Germania, an area east of the Rhine River

in what is now modern Westphalia. Though it was pacified after nearly twenty

years of occupation, the Romans maintained a strong base at Aliso (modern

Haltern) defended by three legions, XVII, XVIII and XIX (18,000 infantry and

900 cavalry), and allied auxiliaries (3,500–4,000 allied infantry and 600 cavalry),

perhaps 23,500 troops all together. The atmosphere in Germania was calm in the

autumn of 9 ce, and the legions were used to Romanize the region, felling trees

and building roads and bridges.

In September the calm was broken by a minor insurrection of

Germanic tribesmen. Setting out for his winter quarters at Minden, Varus

decided to pass through the troubled region. But unknown to him, the

insurrection was orchestrated by one of his own military advisers, Arminius, a

man of Germanic birth who had been granted Roman citizenship and held

equestrian rank. Arminius engineered this uprising in order to draw Varus

through what appeared to be friendly but difficult terrain, with the intent of

annihilating the Roman forces. Although tipped off about the possible plot by a

subordinate officer, Varus disregarded the threat and marched south-west with

his army in column, followed by a long baggage train and the soldiers’

families.

On the second day out, Arminius and his Germanic contingent

suddenly disappeared from the Roman column. Shortly thereafter, reports reached

Varus that outlying detachments of soldiers, probably scouts and foragers, had

been slaughtered. Fearing an ambush in hostile territory, Varus then turned his

column and headed south toward the Roman fortress of Aliso. The march to Aliso

would take the encumbered column through the Doren Pass in the Teutoburg

Forest, between the Ems and Weser rivers. Here, the manoeuvrability of the

column was severely limited by thick woods, marshes and gullies, exacerbated by

seasonal rains and the presence of the heavy baggage train and camp followers.

The first attack on the Roman column took place as Roman

engineers were cutting trees and building causeways in the difficult terrain.

Despite the disappearance of Arminius and his men, Varus refused to take any

special security precautions. Instead, the troops were thoroughly mixed in with

the civilians. As the column slowed and piled up, the wind surged and the rain

began.

In the midst of this confusion, Arminius suddenly struck the

Roman column’s rearguard as his Germanic allies emerged from the woods on the

Romans’ flanks, hurling javelins into the mass of the unformed Roman ranks.

Varus ordered his own auxiliary light infantry to engage the barbarians, but

these troops were Germanic to a man and, either seeing the futility of the

situation or in a prearranged plot, deserted the Romans to join Arminius’

forces. Gradually, the legions formed, but not before taking significant

casualties. As the Roman column’s vanguard prepared for a counter-attack, the

German attackers disappeared as quickly as they had appeared. Roman engineers

sallied out and found some flat, dry terrain and began to construct a field

camp. As the Roman column made its way to the safety of the camp, Varus ordered

his supply wagons burned and nonessential supplies abandoned.

At dawn Varus set out again, this time with his army in

field marching formation (Map 5.2(d)). His objective was Aliso, now less than

20 miles away through the Doren Pass. As the Roman column marched out of the

forest and into open terrain, Arminius’ troops shadowed the invaders,

skirmishing with the Romans at every opportunity, but refusing to engage in

force. The barbarians hurled their javelins into the Roman ranks to good effect,

but without their own light infantry they could not return fire. The situation

became worse when the column entered the woods. The barbarians attacked again

as they had the day before, hurling javelins from the woods and engaging in

small-unit attacks when the terrain and numbers favoured them.

At day’s end, the Romans built a second field camp about a

mile from the opening of the Doren Pass and tended their wounded.

Unfortunately, Varus did not fully understand the magnitude of his strategic

situation. Every major Roman outpost east of the Rhine had been attacked, and

most were overrun. Aliso, his objective, was besieged by Germanic tribesmen and

was barely holding on. Meanwhile, Arminius’ forces were swelling, and soon he

had enough troops to successfully overrun the Roman camp.

Arminius spent the night felling trees to obstruct the floor

of the ravine, forcing the Romans to slow their march and fight for every foot

of passage through the pass. The Germans then took up positions on the hillside

and prepared for the Romans. The following morning, Varus pushed toward the

Doren Pass. As the Romans pressed up the pathway, they began to meet heavy

resistance from Germanic light infantry hailing down missiles from the

hillside. The Romans gradually gained ground, but when a heavy rain began, the

slick surface slowed the Romans’ ascent.

Finally, unable to secure passage through the pass in the

face of inclement weather and a determined foe, the Romans in the van began a

controlled retreat down the ravine. At this moment, Arminius ordered a general

attack, sending his infantry into the ravine to meet the Romans in hand-to-hand

fighting. Germanic swords and javelins struck at Roman cavalry, forcing the

horses back into the Roman infantry. In the midst of the mounting confusion,

Varus ordered a retreat to the base camp. The Roman retreat, which began in

good order, turned into a general rout. Some Roman cavalry broke away from the

column and rode into open terrain, only to be run down by Germanic cavalry.

Back in the ravine, the barbarians cut the column in several places, isolating

and then overwhelming the Roman units. A contemporary historian of the battle

notes that the Roman army ‘hemmed in by forests and marshes and ambuscades was

annihilated by the very enemy that it had formerly butchered like cattle’.

At Teutoburg Forest, three Roman legions and 10,000 camp

followers were killed during two days of intensive fighting. Like the battle of

Carrhae half a century earlier, the Romans lost because they were unable to

compel their enemy to meet them in close-quarter combat. The Germanic light

infantry used terrain to good effect, ambushing the Romans and attacking at a

distance with javelins, then disappearing back into the forest. This form of

‘hit and run’ tactic wore down the Romans, forcing the legions, in the words of

recent authorities on the battle, to ‘die a death of a thousand cuts’. When

close battle was finally offered, the Roman heavy infantry was in full retreat,

discouraged, disorganized and overwhelmed by a numerically superior foe. But

even under these dire circumstances, the Romans fought in small units for

hours, meeting and beating wave after wave of barbarian attackers. One small

troop of legionaries fought on throughout the day and into the next, being

overcome by the barbarians the following morning and killed on the spot.

As a consequence of this defeat, the Romans never occupied

more than the fringe areas of Germania, instead relying on the Rhine and Danube

rivers as a natural barrier demarcating the Roman Empire’s northern border.

Territorial expansion did take place under the successors of Augustus, but with

the exception of the annexation of Britain by Claudius (r. 41–54 ce) in 43 ce,

the expansion remained within the natural frontiers of the empire – the ocean

to the west, the rivers to the north and the desert in the east and south.

Still, three areas prompted special concern. In the east, the Romans used a

system of client states to serve as a buffer against the Parthians. In the

north, the Rhine–Danube frontier became the most heavily fortified frontier

area because of the threat from Germanic and Asiatic tribes, while in the

north-west, Britain served as a safe harbour for Celtic tribes, prompting the

Romans to cross the English Channel and challenge the barbarians for mastery of

the island.

Legion versus Chariots: The Roman Campaigns in Britain

Rome’s first foray into Britain took place in August 55 bce

when Julius Caesar led two legions in a reconnaissance expedition against the

Celtic tribes. By then three years into a very successful Gallic campaign,

Caesar set his sights on the relatively unknown island on the edge of the known

world, perhaps wishing to secure a piece of the tin trade or possibly to gain

more political fame in Rome by subduing yet another foe. Caesar returned to

Britain in the following summer with five legions, landing north-east of Dover

in modern Kent. Pushing through weak resistance on the beachhead, Caesar

marched inland and crossed the Thames River near Brentford. The British chief

Cassivellaunus avoided a large battle against the Romans, instead harassing the

invaders with war chariots and cavalry raids.

This meeting between Roman legion and Celtic chariots was in

essence an encounter between the finest Iron Age army of the classical period

and a battlefield anachronism whose origins dated back to the Bronze Age. Yet,

despite never meeting the Britons in a pitched battle, Caesar was impressed

with the barbarians’ chariots, describing their harassing tactics in his Gallic

Wars:

They begin by driving all over the field, hurling javelins;

and the terror inspired by the horses and the noise of the wheels is usually

enough to throw the enemy ranks into disorder. Then they work their way between

their own cavalry units, where the warriors jump down and fight on foot.

Meanwhile the drivers retire a short distance from the fighting and station the

cars in such a way that their masters, if outnumbered, have an easy means of

retreat to their own lines. In action therefore, they combine the mobility of

cavalry with the staying power of foot soldiers. Their skill, which is derived

from ceaseless training and practice, may be judged by the fact that they can

control their horses at full gallop on the steepest incline, check and turn

them in a moment, run along the pole, stand on the yoke, and get back again

into the chariot as quick as lightning.

Perhaps recognizing the capabilities of Caesar and his

veteran legions, Cassivellaunus finally agreed to peace terms at Verulamium

(modern St Albans, 20 miles north-west of London), surrendering hostages and

agreeing to pay tribute to Rome. Satisfied, Caesar retraced his route to the