Tankettes

The Japanese Army essentially employed three categories of tank during the Second World War. Almost all these vehicles, regardless of category, were rather small by western standards. Their fighting compartments tended to be cramped, even for the smaller physique of the average Japanese (I can’t cite the source but remember reading that the statistical average height for recruits accepted into the Japanese Army during World War II was five feet three inches). Perhaps most importantly, just about all of the Japanese tanks compared badly with many contemporary European and American designs in terms of such qualities as gunpower and armor thickness. However, before judging the Japanese too harshly on account of the latter, it should be remembered that the Japanese Army was not planning to fight on the open steppes of southern Russia or the hedgerows of Normandy, where tank versus tank confrontations were frequent, and the European opponents were relatively close to their own bases of power. The Japanese war would take place on the other side of the world, in Asia and on various Pacific islands. Here the opposition would either be the other independent or semi-independent Asian countries, who would have only small quantities of light armor, if indeed they possessed armored vehicles at all; or else western colonial powers, the European component of which was already involved in an all-consuming war closer to home, all of whom would be fighting at great distances from their native lands, and at the end of a very long supply line. In these conditions the technical qualities of the Japanese tanks were often secondary to the very fact that they had tanks available at all, since (at least during the Japanese period of conquest in the early part of the war) mere possession of tanks often proved a great advantage, as their enemies did not have any.

Japanese armor is often dismissed rather hastily in writing about the Second World War, in part because of the small size and general unimpressiveness of most Japanese designs (at least by European standards), and also because of the relatively limited numbers of tanks the Japanese were able to produce during the war. In the entire period 1931-45 the Japanese built barely 6,500 tanks of all kinds (Mitsubishi, the most important firm in Japanese tank production, made 3,300, or just over half of these). That quantity may seem trifling compared to some of the other combatants– for instance, the Germans built more than 20,400 battle tanks of over ten tons alone (and another 14,000 self-propelled guns), the Americans churned out some 49,000 Shermans– not to mention their other types!– in 1942-45, the Soviets produced some 40,000 T-34’s alone 1940-45, and the British made 8,600 tanks of all models in a single year, 1942. But Japan’s other Axis ally, Italy, was able to complete only a little over 2,000 battle tanks over ten tons during the war, and perhaps an additional 2,500 light tanks and tankettes. And the hapless Italians were indeed deeply involved in 1940-42 in a theatre (North Africa) where tanks were often the decisive arm, and where sizeable tank- versus-tank battles were the rule rather than the exception. More to the point, despite the relatively anaemic overall production (a result of both an industrial base too small to sustain all the demands of total war against such powerful enemies; a scarcity of raw materials which drove the Japanese to initiate the war with the westerners in the first place, and which grew much worse in the second half of the conflict; and, lastly, of the relative priorities accorded tank production in the allocation of scarce materials and facilities), Japanese tanks did appear on a wide number of battlefields throughout Asia and the Pacific. And, as will be seen below, they often made a significant contribution to victory in the period of greatest Japanese success. Their significance in the Far Eastern conflict may well be underrated.

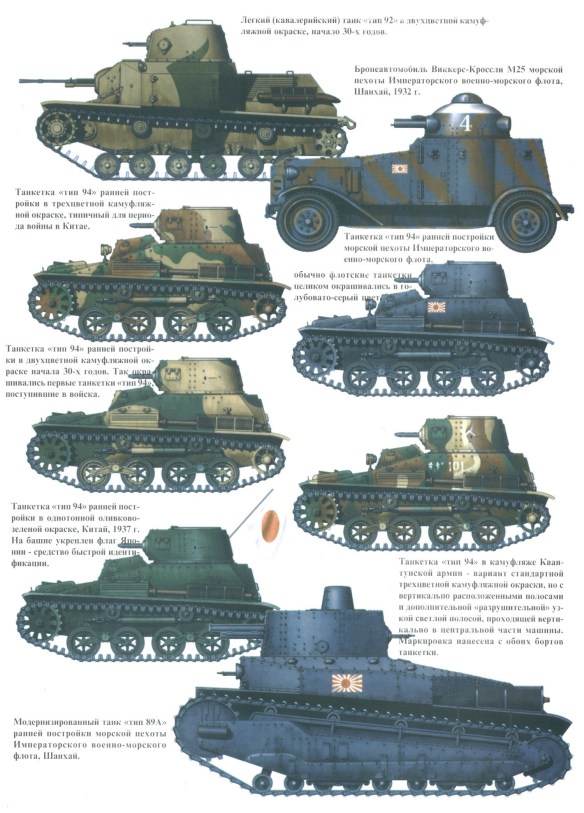

The smallest of the three main categories of Japanese tanks was not a tank at all, really, but rather a “tankette.” That is what its British designers called it, at any rate, and in the late 1920’s they sold these little tracked vehicles, with or without turret, to a plethora of countries not only throughout Europe but all over the world. Many of the major European countries which acquired examples– for instance, Germany, the USSR, Italy, Poland– subsequently modified and developed the designs to suit their own specifications, and this was true for Japan as well. Like the Italians and the Poles (and many smaller nations), the Japanese at first were interested in using the tankette as a reconnaissance vehicle, specifically (again like the Italians and the Poles) to support the horse cavalry that usually carried out the task of scouting in these armies. Having one or more mobile, armored machinegun nests– which was essentially what the tankette was, in its most common variations– to call upon for quick back-up seemed like a good idea to most of the horse troopers. The Japanese, though, came to also use the tankette in their infantry divisions, performing a direct reconnaissance role either as a substitute for the horse cavalry, or as a supplement to what was available.

The chief Japanese tankette during World War II was easily the Type 97, also known as the “Te-Ke” (I believe this was just a Japanese phoneticizing of the abbreviation “TK” for “tankette”– as opposed to tank– a designation which was also retained by the Poles for their vehicles of this class). It was a small, four and a half-ton vehicle, with two crewmen– a driver in the hull and a gunner, who was also vehicle commander, in the turret. The normal armament in that turret was a single 37mm cannon. The Type 97 did not carry a machinegun, although there was a variant wherein a 7.7mm machinegun replaced the 37mm gun as the tankette’s sole weapon. However, the version with the cannon seemed to have been by far the most prevalent, at least by the time of Pearl Harbor. The Type 97’s armor was about two thirds of an inch thick (16mm) on its front surfaces, at other places (like its belly) well under a quarter of an inch (4mm). With an acceptable but unspectacular road speed of about 25 miles per hour, it was hardly an overpowering fighting machine in any respect. Nonetheless, the Type 97 proved extremely versatile. As mentioned, its initial role was supposed to be reconnaissance, but often these little tankettes were forced into battle in an infantry support role, leading or closely following groups of riflemen in attack in lieu of regular tanks to perform that function. Some of the Type 97 tankettes were also employed as armored front-line observation posts, often for use by artillery forward observers. Not only was the Type 97 Te-Ke, therefore, utilized for infantry support, as a sort of armored cavalry, and by the artillery arm, but it also saw service in supply tasks. The vehicle was rather widely used as a front-line armored ammunition carrier (the Japanese even built a small trailer for the Type 97 in this role, although these did not always accompany the tankette when in an ammunition-carrier capacity. I’m not sure if the trailer was armored or not).

Because of its versatility and general usefulness, the Type 97 was encountered virtually everywhere the Japanese Army fought during World War II. But it was seldom encountered in any great numbers. The Japanese generally did not group their tankettes into units larger than a company, which would be anywhere from 10 to 17 vehicles, and a total of at least 80 men including the organic supply and maintenance personnel and the command staff. Most regular Japanese divisions were organized to include a so-called “infantry group,” which essentially consisted of a separate headquarters establishment which directly controlled the division’s three infantry regiments, subordinate to divisional headquarters. In addition to the 70-110 men comprising the “infantry group” HQ, that headquarters also normally controlled one tankette company, as its own separate reconnaissance resource. This was the case, at least, in the type “B” divisions which made up the bulk of the Japanese Army, and most of the units employed against the westerners.

The Japanese also used considerable numbers of the older Type 94 tankette, especially in China (and China, where security duties and counter-insurgent warfare made huge demands on the Japanese forces throughout the Second World War, was a theatre and a type of fighting where older armored vehicles could remain useful far beyond their prime). The machinegun-armed Type 94 tankette was chiefly used in China after 1941, but this was not exclusively so, and the British, for example, encountered a few in Burma in 1942 and after. Even smaller than the Type 97 Te-Ke, it weighed less than three and a quarter tons. Like the Type 97, the Type 94 had a two-man crew. Its small, offset turret housed a single 7.7mm machinegun, and was so primitive that the means of traverse was by the crewman inside pushing it around with his shoulder! Armor was at most only half an inch thick (12mm), and speed 25 mph on a good road. Japan’s first tankette design, the Type 92, also remained in service in China (there is some confusion because for a time the Type 94 was mistakenly called the Type 92 by the Allies, but both vehicles were employed, the Type 94 in greater quantity by 1941). Like the Type 94, the Type 92 was a two-man tankette mounting a single machinegun in its turret.

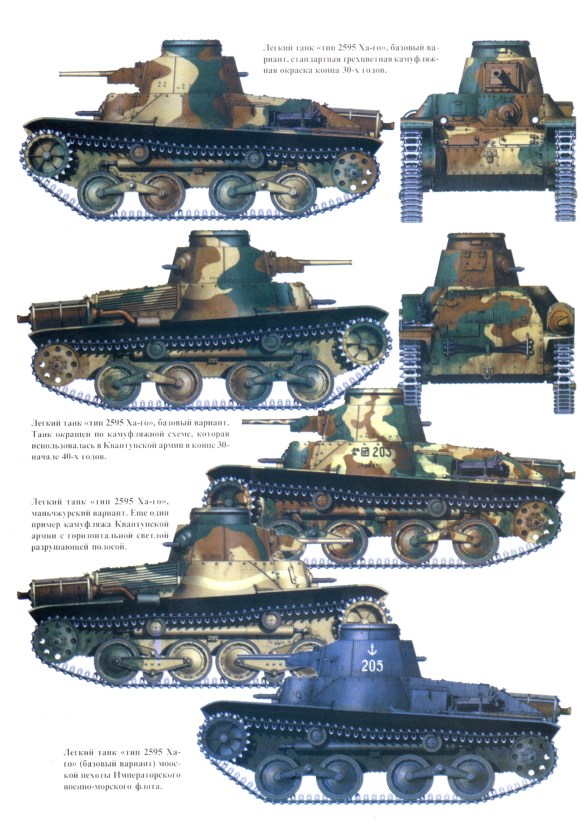

The Japanese tankettes were in reality auxiliary vehicles, designed and adapted for a variety of support tasks. The true battle tanks were grouped into two different categories, light and medium. The most numerous light tank in December 1941, and in fact throughout most of the war, was the Type 95 or “Ha-Go.” In fact, this was probably the most numerous type of tank in the Japanese forces at the time of Pearl Harbor. The Ha-Go weighed seven and a half tons, and accomodated a crew of three. In the hull the driver and a machinegunner sat side-by-side (if the tank had a radio, which few Japanese vehicles did prior to the end of 1942, at least, the bow machinegunner was also the radio operator). The third man was in the turret, which had a 37mm gun mounted in the front, and the tank’s second 7.7mm machinegun in its rear, in a ball mount (hence hand-aimed by the crewman in the turret). The fellow in the turret therefore had plenty of tasks to keep him busy. First and foremost, he was the vehicle commander, which meant he had to maintain contact with the other tanks in his unit, keep an eye out for the enemy, constantly evaluate the situation and decide what to do from moment to moment, convey those intentions to the rest of his crew through orders, and, as in many tanks of the period, since he had the best view he would frequently find himself helping to direct the driver, whose field of vision when “buttoned up” was much more limited. In addition to all that the man in the turret had to fire both the cannon and the machinegun (both of which were of course pointing in opposite directions) as suitable targets presented themselves, which also meant ensuring that the turret was pointing the right way to do so, and he also had to reload these weapons as required (which for the 37mm gun was after every shot). And if by chance the tank commander was also the commander of his unit, he had to do all that while doing the thinking for his entire command. The restricted working space within the vehicle’s cramped interior did not render his multitude of tasks any easier.

The Type 95 was not well-protected, with armor to a maximum thickness of only 12mm, and not particularly well-shaped (and, of course, a round which penetrated the Ha-Go’s crowded fighting compartment was almost certain to hit part of a crewman’s body and/or something which would explode or catch fire). The Ha-Go’s best feature was its mobility, capable of a respectable 28 mph on a good road. Furthermore, there was one design area in which the Japanese most definitely got things right, and that was in the provision of diesel engines for their battle tanks, including the Type 95. This might seem a relative no-brainer in a nation which started the war primarily over disputes regarding oil supplies. At any rate, the Ha-Go could drive up to 130 miles between fill-ups, which was a useful characteristic in an Army that was often resource-starved.

The Type 95 was virtually ubiquitous during the great initial tide of conquest, appearing wherever Japanese battle tanks were employed. However, in 1942 the Ha-Go was phased out of production. This was because a newer and better design of light tank had appeared, the Type 98 or “Ke-Ne.” Rather than simply upgrade the tested but aging Ha-Go, the Japanese had opted for a fairly complete redesign. The new vehicle was a bit lighter than the Type 95, weighing just under seven and a quarter tons. It too carried a three-man crew, but now only the driver was in the hull. This meant that the vehicle commander had an assistant with him in the turret to help with such mundane tasks as reloading the 37mm. There was no hull machinegun, and no mg in the rear of the turret. In the Type 98 the machinegun was mounted co-axially with the 37mm cannon that remained the tank’s main armament. Thus both could be traversed, elevated, and aimed by the same mechanism. The Ke-Ne’s armor was no thicker than that on the Ha-Go, a mere 12mm at most, but it had been extensively reshaped, and was much more highly sloped to provide a greater chance of enemy rounds glancing off. Finally, the Type 98 got both a new engine and a better suspension, giving it a very good top speed of over 31 mph.

All in all, the Type 98 was much better than the venerable Ha-Go, but nonetheless it never succeeded in completely replacing the older vehicle during the war. In part this was due to the difficulties inherent in re-tooling to make a new model tank which differed in so many details of design from its predecessor, hence would require a multitude of completely new parts. In part it reflected the diminished need for light tanks in general by the second half of 1942, when the Ke-Ne was beginning to enter production. By that time the Japanese were fully on the defensive in many areas (light vehicles whose best qualities are their mobility being more suited to the requirements of offensive warfare), and furthermore they had by now recognized that the tendency in the present war was toward the construction of ever heavier combat tanks. These factors combined to limit the total production of the Type 98 to less than 200 vehicles. the record, the model I mentioned that was supposed to succeed the Type 98 (Ke-Ni) was the “Ke-To.” It was so heavily based on the Ke-Ni that just about the only appreciable difference was the provision of a 37mm main gun with slightly increased velocity. It is not surprising that the Japanese Army saw no reason to rush this little tank into action, although beginning in 1944 a few were made and deployed to units. The number, however, remained very small. Thus the little Ha-Go remained in action, even up to the decisive battles of 1944-45, almost a decade after it first entered service (this was especially true in tank units which had been deployed overseas in the first year of the war, and which subsequently remained in operational theatres, with very limited opportunities for re-equipment).

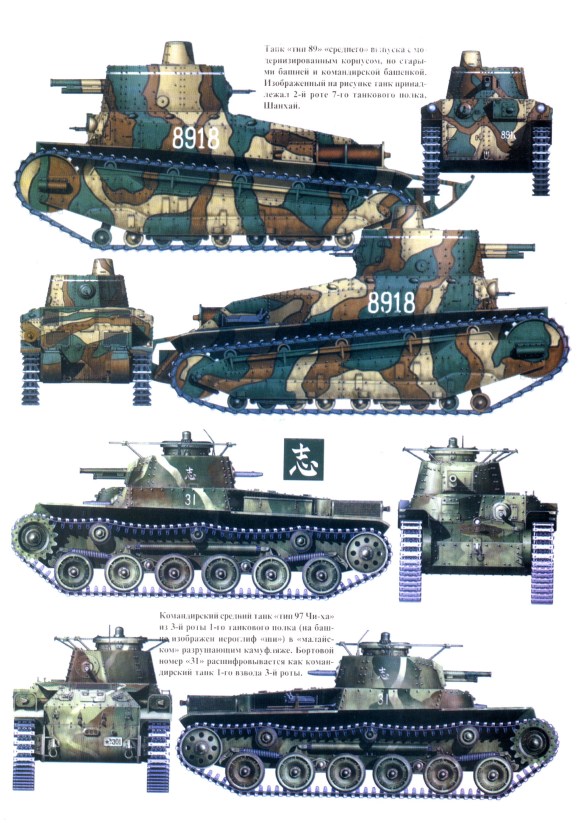

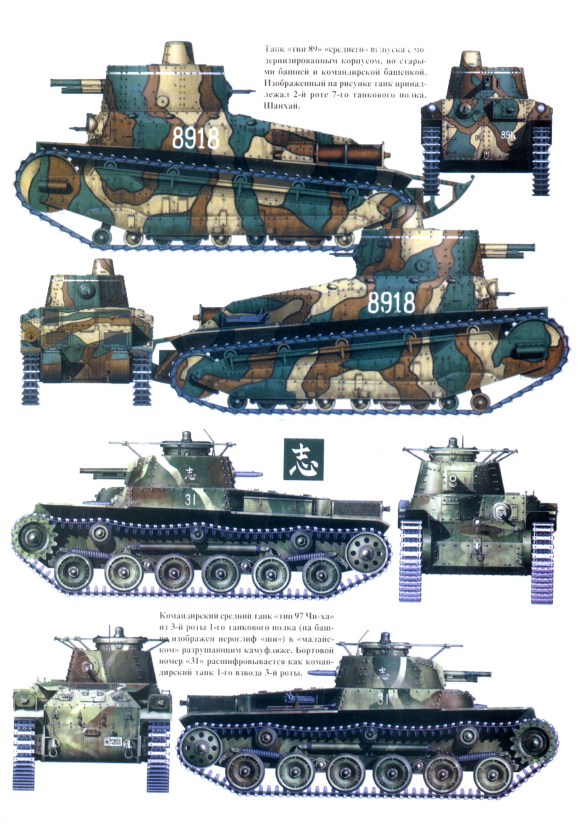

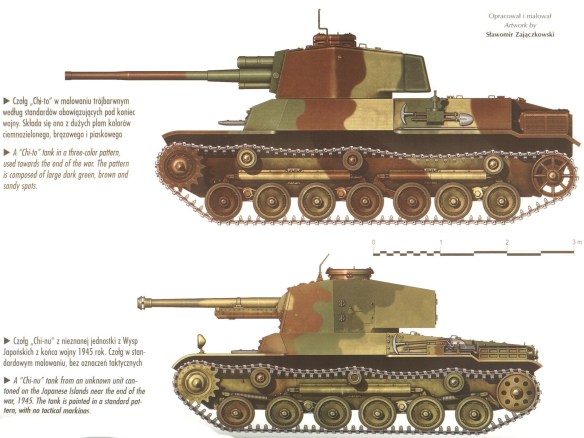

The tank regiments into which the Japanese battle tanks were usually formed in general consisted of roughly equal numbers of light and medium types. The medium tanks were the heaviest category of Japanese armored vehicles. The principal model in service at the time of Pearl Harbor was the Type 97 or “Chi-Ha.” It was a machine of about 15 tons, carrying a crew of four– two each in the hull and the turret. This was the newest tank in the Japanese Army at the start of 1941, as well as the biggest. It mounted a short 57mm gun in the front of the turret, with the conventional Japanese arrangement of two 7.7mm machineguns, one in the front of the hull and the second in the rear of the turret. The 57mm cannon, with its low velocity, was of very little use in engaging enemy tanks. Its intended role was to deal with machinegun nests and other field fortifications that might impede the infantry, preferably by firing directly into them at short range. The Chi-Ha had armor up to an inch thick (25mm). It was not particularly fast, managing less than 24 mph even on roads. It did however possess a diesel engine which gave an adequate range.

Far from overpowering compared to many European tanks in 1941, the Chi-Ha had still not completely replaced the even more outdated old Type 89, Japan’s first true medium tank. This was a vehicle of 13 tons, with the same armament scheme as the Chi-Ha (short 57mm gun and two machineguns, the latter mounted in a similar lay-out), and it also took a four-man crew. But it had even less protection than the Type 97 (17mm maximum armor), it was much slower (just over 15 mph tops), and it had a rather high silhouette for such a light vehicle, with a prominent sloping front hull (not entirely unreminiscent of the American Sherman). The Type 89 was so unwieldy that most of the ones remaining in service were fitted with a sort of tail to ground them and prevent them from tipping over backwards when traversing particularly uneven ground, or crossing shell holes and ditches. Still, this ancient tank remained in use not only in China (of course), but a fair number were also present supplementing the Chi-Ha in the medium tank units of Yamashita’s 25th Army during its invasion of Malaya and Singapore, and a few also saw action in Burma before being either retired or relegated to the China theatre by mid-1942. In the Malayan campaign, at least, they shouldered the same combat burdens as the newer Chi-Ha’s and the light Ha-Go’s, and this was in many ways their last great hurrah in the war.

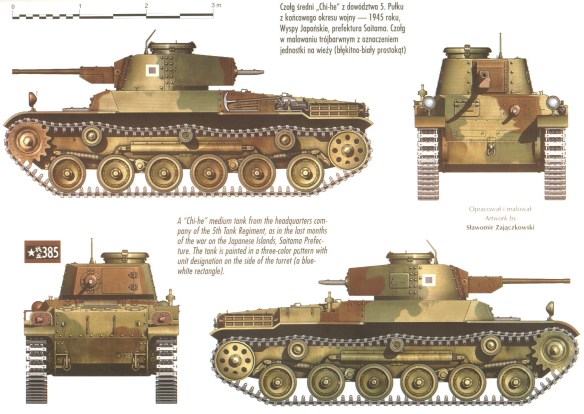

Although at this time they had still not completely replaced even the old Type 89 with the Chi-Ha, in 1941 the Japanese Army had introduced a new and improved medium design, the Type 1 or “Chi-He.” Though incorporating some design principles of the Chi-Ha, the Chi-He was a major improvement which differed from its predecessor in many important respects. At 17 tons, it accommodated a five-man crew, which meant three men within an enlarged turret (the arrangement generally felt to be the most efficient by most nations in the war). The turret gun was the 47mm, an adaptation for tank use of the new antitank gun being introduced in the Japanese Army at large in 1942 (and itself adapted from a high-velocity light naval cannon). This weapon packed considerably more penetrating power than the 37mm gun used in the Ha-Go and the Type 97 tankette (which was based on the previous generation of Japanese Army antitank gun)– a reflection of the understanding that a creditable capacity to engage enemy armor was now a basic part of the World War II tank’s job description. Whereas the Japanese 37mm antitank gun (as mounted, in only slightly modified form, in the aforementioned Ha-Go and Type 97 Te-Ke) had a maximum penetration of about an inch and a quarter (32mm) at 500 yards, the 47mm gun could smash through better than two and three-quarters inches of plate (70mm) at the same range (these tests however being conducted against armor at zero degrees– i.e., not sloped at all– hence representing a “best-case” scenario). The Chi-He also carried two machineguns, one each in bow and turret. Its own armor was increased to two inches (50mm) on front surfaces, and the combination of bigger engine and better suspension design gave a pretty good top speed of 27 mph on roads. In short, the Chi-He was in every way better than the Chi-Ha it was meant to replace.

Although at this time they had still not completely replaced even the old Type 89 with the Chi-Ha, in 1941 the Japanese Army had introduced a new and improved medium design, the Type 1 or “Chi-He.” Though incorporating some design principles of the Chi-Ha, the Chi-He was a major improvement which differed from its predecessor in many important respects. At 17 tons, it accommodated a five-man crew, which meant three men within an enlarged turret (the arrangement generally felt to be the most efficient by most nations in the war). The turret gun was the 47mm, an adaptation for tank use of the new antitank gun being introduced in the Japanese Army at large in 1942 (and itself adapted from a high-velocity light naval cannon). This weapon packed considerably more penetrating power than the 37mm gun used in the Ha-Go and the Type 97 tankette (which was based on the previous generation of Japanese Army antitank gun)– a reflection of the understanding that a creditable capacity to engage enemy armor was now a basic part of the World War II tank’s job description. Whereas the Japanese 37mm antitank gun (as mounted, in only slightly modified form, in the aforementioned Ha-Go and Type 97 Te-Ke) had a maximum penetration of about an inch and a quarter (32mm) at 500 yards, the 47mm gun could smash through better than two and three-quarters inches of plate (70mm) at the same range (these tests however being conducted against armor at zero degrees– i.e., not sloped at all– hence representing a “best-case” scenario). The Chi-He also carried two machineguns, one each in bow and turret. Its own armor was increased to two inches (50mm) on front surfaces, and the combination of bigger engine and better suspension design gave a pretty good top speed of 27 mph on roads. In short, the Chi-He was in every way better than the Chi-Ha it was meant to replace.

However, the new medium tank, scheduled to begin full production in 1942, immediately ran into difficulties reaching that status. Much of this was due, once more, to the problems of a rather extensive re-tooling necessary before Japanese factories could start making the new vehicle. As time passed the increasing shortage of the important raw materials used in its manufacture also became a factor, as did the increasing Japanese emphasis on giving priority to aircraft production in allocating materials, factory space, and workers. Thus the Chi-He never reached the forces in the field in anywhere near the quantities which were originally intended.

However, the new medium tank, scheduled to begin full production in 1942, immediately ran into difficulties reaching that status. Much of this was due, once more, to the problems of a rather extensive re-tooling necessary before Japanese factories could start making the new vehicle. As time passed the increasing shortage of the important raw materials used in its manufacture also became a factor, as did the increasing Japanese emphasis on giving priority to aircraft production in allocating materials, factory space, and workers. Thus the Chi-He never reached the forces in the field in anywhere near the quantities which were originally intended.

As a result of the delays in getting the Chi-He to full production status, and of the mere trickle of vehicles completed during the first year or two of its manufacture, the decision was also made to modify and upgrade the existing Chi-Ha, to bring it more in line with modern requirements. This resulted in the so-called “Shinhoto Chi-Ha” or “modified turret Chi-Ha.” The idea was to mount a new turret, capable also of mounting the high-velocity 47mm gun (and in some respects a scaled-down version of the Chi-He turret) on the current Chi-Ha chassis. In terms of mass production, this was an excellent solution. Since the turret ring remained the same size, the vehicle was hardly altered from the hull down, therefore requiring much less in the way of re-tooling. It was even possible to simply fit new turrets on existing hulls. The “Shinhoto Chi-Ha” therefore was a practical expedient, and, entering service during 1942, it rather than the better Chi-He became the principal Japanese medium tank for most of the remainder of the war. With the new turret the “Shinhoto Chi-Ha” weighed a little over fifteen and three-quarters tons, but otherwise it remained essentially the same vehicle as the original Chi-Ha (the new turret also retained the normal Chi-Ha’s maximum armor of 25mm, although some of the later models increased this to 50mm, like the Chi-He). The crew of the “Shinhoto Chi-Ha” stayed at four men.

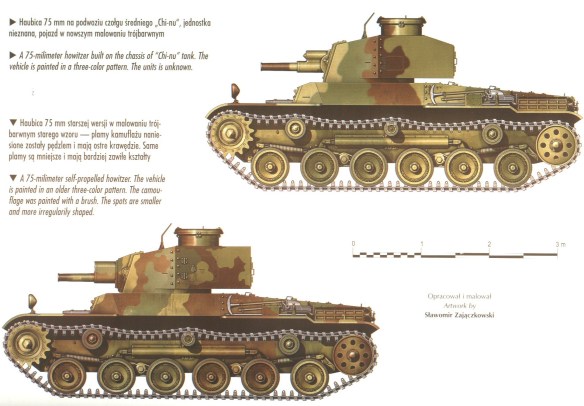

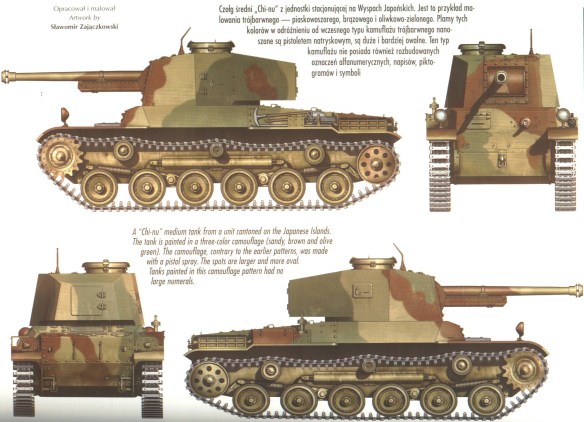

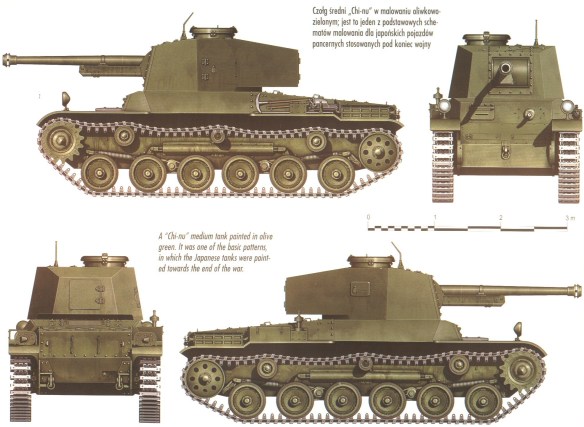

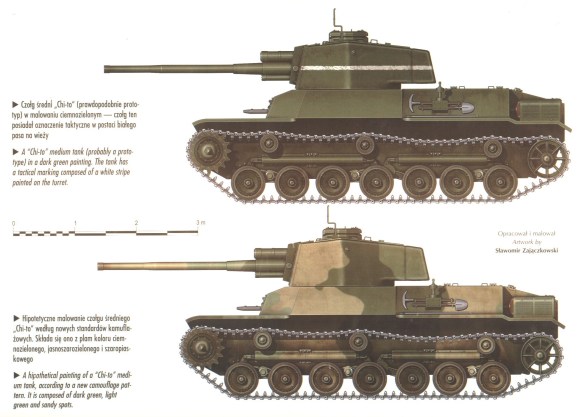

Despite the difficulties in getting the Chi-He into service in large enough numbers, the Japanese pressed on with the design of bigger and better medium battle tanks. In 1944 a new model, the Type 3 or “Chi-Nu,” was in theory ready to start production. This was basically the Chi-He chassis modified to take a larger turret, big enough to house a 75mm gun of reasonable velocity. The cannon was in fact the tank-mounted variant of the Type 90 gun, a Japanese adaptation of the French Schneider 75mm field gun (the “French 75” of First World War fame) to an antitank role (with considerably changed appearance but essentially the same ballistics as the original French gun), which the Japanese Army was trying (in, as it turned out, very limited numbers) to introduce as a heavy antitank gun in the final years of the war. The new turret had little room for anything besides the 75mm gun and three crewmen. The Chi-Nu therefore had only one machinegun, in the front of the hull. It weighed eighteen and a half tons, and took a total crew of five men. Top speed was about 24 mph on a good road, and the armor remained a maximum of 50mm thick in front. Though it was the first Japanese tank with a gun capable of competing with that on western designs like the American Sherman on something like equal terms, this was almost irrelevant. For although production began in 1944, the number built remained small, and a few of the limited numbers of Chi-Nu’s built ever left Japan, most being retained by the forces the Japanese were organizing to defend their own country against a projected US invasion in the war’s final year.

Despite the difficulties in getting the Chi-He into service in large enough numbers, the Japanese pressed on with the design of bigger and better medium battle tanks. In 1944 a new model, the Type 3 or “Chi-Nu,” was in theory ready to start production. This was basically the Chi-He chassis modified to take a larger turret, big enough to house a 75mm gun of reasonable velocity. The cannon was in fact the tank-mounted variant of the Type 90 gun, a Japanese adaptation of the French Schneider 75mm field gun (the “French 75” of First World War fame) to an antitank role (with considerably changed appearance but essentially the same ballistics as the original French gun), which the Japanese Army was trying (in, as it turned out, very limited numbers) to introduce as a heavy antitank gun in the final years of the war. The new turret had little room for anything besides the 75mm gun and three crewmen. The Chi-Nu therefore had only one machinegun, in the front of the hull. It weighed eighteen and a half tons, and took a total crew of five men. Top speed was about 24 mph on a good road, and the armor remained a maximum of 50mm thick in front. Though it was the first Japanese tank with a gun capable of competing with that on western designs like the American Sherman on something like equal terms, this was almost irrelevant. For although production began in 1944, the number built remained small, and a few of the limited numbers of Chi-Nu’s built ever left Japan, most being retained by the forces the Japanese were organizing to defend their own country against a projected US invasion in the war’s final year.

Still, the Japanese designers, at least, kept working. In 1944, with the Chi-Nu proceeding to production status (at least on paper), they unveiled the ultimate tank to exist in concrete form for the Japanese Army during the war, the Type 4 or “Chi-To.” This was by far the biggest armored fighting vehicle developed by the Japanese during the war, coming in at 30 tons. It was again a fairly thorough re-design. The Chi-To’s main gun was a 75mm, but this was an adaptation of the Type 88 antiaircraft gun, with a longer barrel and a considerably greater velocity (hence better penetrating power) than the Type 90 75mm. The Chi-To also carried two machineguns, one in the front of the hull, the other mounted co-axially with the main gun in the turret. With the standard crew of five, its frontal armor was now three inches (75mm) thick. A new V-12 diesel engine delivered a top speed of 28 mph, quite respectable for its size. This would have been by far the best tank used by the Japanese Army in the war, and the first one which stacked up decently against European and American designs in use in 1944-45. However, it never entered production at all. A total of only six examples, all prototypes, were constructed. By 1945 Japanese industry in general, and especially the sort of heavy industry concerned with tank production, was on the ropes, being systematically eradicated or relegated to insignificance by the direct attacks of American bombers targeting the factories, and the indirect (but possibly even more crippling) effects of a highly successful blockade of the Japanese home islands by US submarines, Allied aircraft, and, more recently, extensive mining of the waters surrounding Japan by American planes. In these conditions there was no chance that such a large and material-consuming piece of hardware like the Chi-To (or even the Chi-Nu) would ever see the light of day in numbers large enough to make the slightest difference.