Preparing for World War II

The development of the Italian Navy’s “special

attack” weapons was stimulated in 1935 by the international tension

consequent upon Mussolini’s Abyssinian adventure. In September of that year,

two young naval engineers, SubLt Teseo lbsei and SubLt Elios Toschi, submitted

a plan for a manned‑torpedo based on the Leech but with significant

improvements‑notably the capability of travelling fully submerged over short

distances. The design was quickly approved by Admiral Domenico Cavagnari and

two prototypes were built at the San Bartolomeo Torpedo Workshops, La Spezia.

In January 1936, crewed by its inventors, the weapon ran successful secret

trials, and later in the year the training of manned torpedo personnel was

begun under Cdr Catalano Gonzaga di Cirella, commanding 1st Submarine Flotilla.

The pace of development slackened as the Abyssinian crisis

passed, but picked up again with increasing threats of war in 1939. The programme

was now under the direction of Cdr Paolo Aloisi of the 1st Light Flotilla;

Tesei and Toschi, now promoted and relieved of all other duties, made further

design improvements to their manned‑torpedo. Early in 1940, three manned‑torpedoes

were launched from the submarine Ametista

(Cdr J. Valerio Borghese) in the Gulf of Spezia: in a mock‑attack by night,

one succeeded in penetrating the harbour of La Spezia and fixing a dummy charge

to the hull of a target ship. According to Borghese’s account, a short‑wave

radio link to guide the torpedoes back to the mother boat was tested then but

was not proceeded with‑largely because the torpedoes’ operators felt that any

provision made for their return might affect their determination to succeed at

all costs. (This was an argument used by Japanese servicemen who opposed the

fitting of ejector‑seats in explosive motorboats and escape hatches in kaiten;

weapons which they, if not the high command, acknowledged to be suicidal.)

Further, Borghese quotes Tbsei (whose suicidal end at Malta in July 1941 is

described on pages 81‑82) as declaring that “what really counts is that

there are men ready to die . . . [to] inspire and fortify future generations .

. .”

The “Maiale” Manned‑Torpedo

As a result of the successful exercise, the construction of

a first batch of 12 manned‑torpedoes at San Bartolomeo was ordered. Officially,

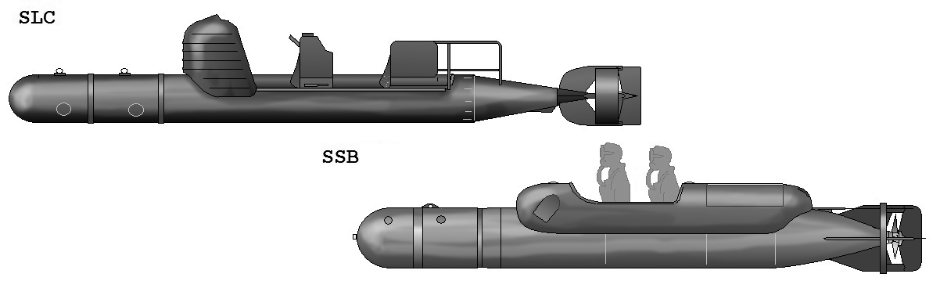

the weapon was designated the SLC (Siluro

a lenta corsa, “Slow‑running Torpedo”); to the men who manned it,

it was almost always known, probably because of its frequent perversity in

handling, by the covername of Maiale (“Pig”).

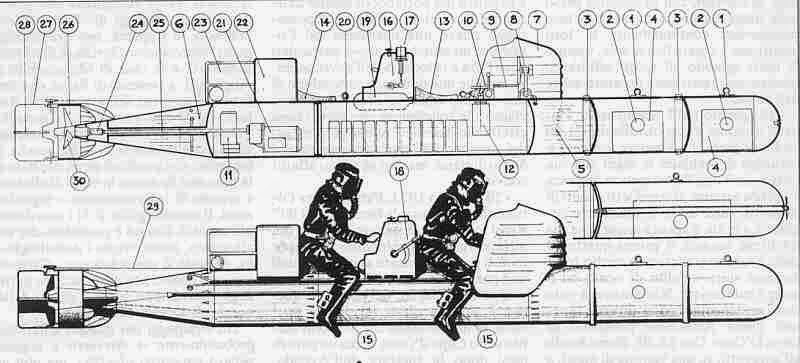

The Pig was 22ft (6.7m) long overall and 1.8ft (533mm) in

diameter, displacing 1.5 tons (1.52 tonnes). It was powered by a l.1hp (later

uprated to 1.6hp) electric motor, giving near‑silent running at a maximum 4.5kt

(5.2mph, 8.3kmh) to a range of 4nm (4.6 miles, 7.4km ) or at 2.3kt (2.6mph,

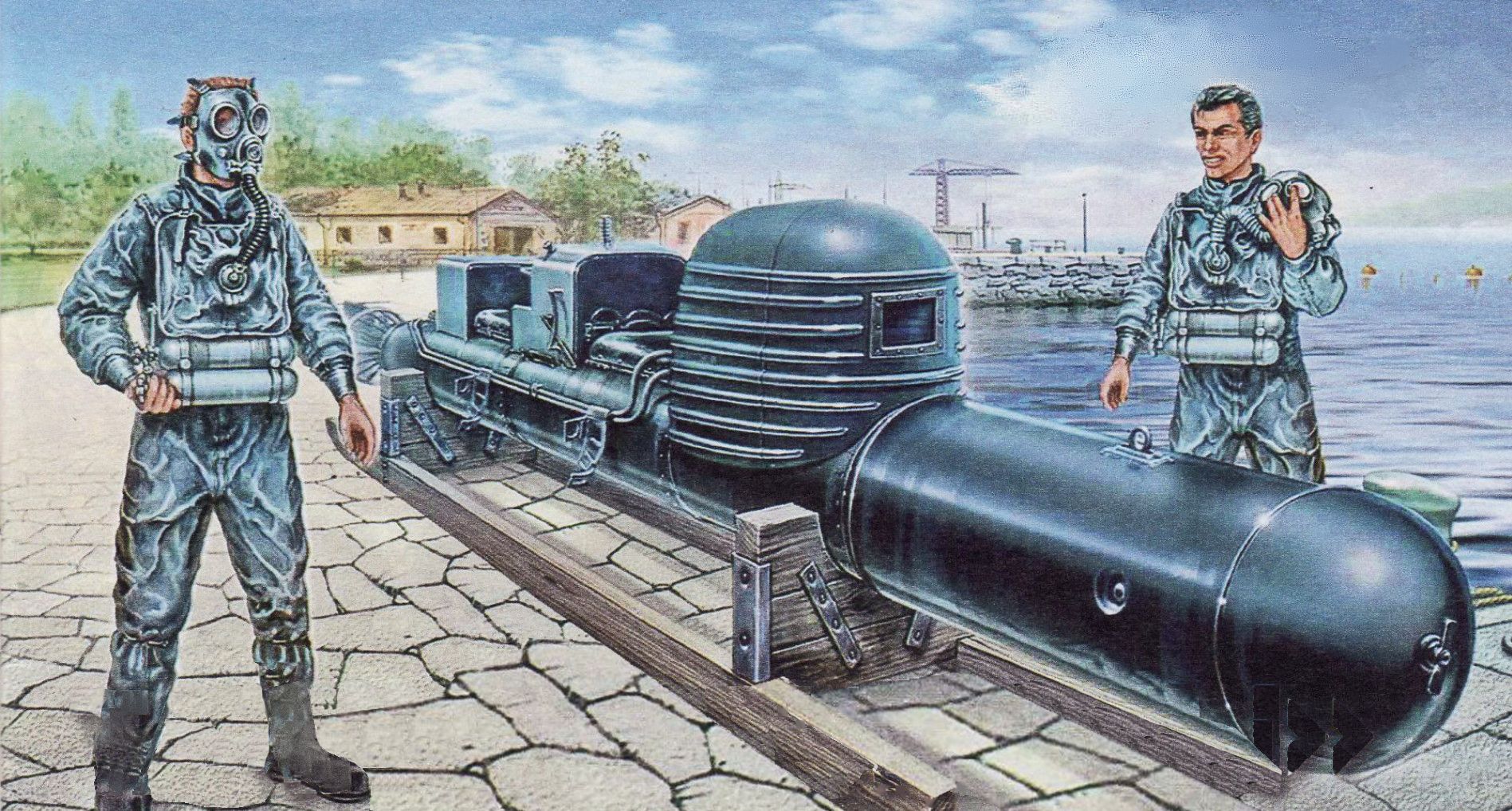

4.25kmh) to a range of c.15nm (17 miles, 28km ). Its crew were clad in

protective rubber suits and equipped with self‑contained breathing‑apparatus

fed by a six‑hour supply of bottled oxygen, and the Pig was capable of full

submergence, to a safe depth of c.l00ft (30m), over a fairly short distance.

The bow‑mounted detachable warhead was at first of 4851b (220kg) explosive

weight, later rising to 5501b (250kg) and at last to 6601b (300kg). A time‑fu

allowed up to five hours’ delay in detonation.

The Pig’s operators sat astride their craft with their feet

held place by metal stirrups. The officer‑pilot, forward, was protected b3

chest‑high curved metal screen on which was mounted a luminous magnetic

compass, a depth‑gauge, a spirit‑level, and instruments f monitoring the

electric motor. He controlled the rudders with steering‑column of aircraft

type; trim‑levers admitted water to “blew” the tanks. Separated from

the pilot by the protuberance of t crash immersion tank, the co‑pilot (usually

a petty‑officer/diver) s with his back against a metal storage locker

containing spare breathing gear and tools.

In the last few of the 80‑plus Pigs built in 1940‑43, the

operators were provided with greater security by the provision of an over;

metal casing, which gave the craft an appearance something like that of a dual‑cockpit

aircraft fuselage. These later examples, called the SSB (Siluro San Bartolomeo, “San Bartolomeo Torpedo”), a

believed to have been of improved performance; their operation deployment was,

however, forestalled by Italy’s collapse.

Transport to the Attack Zone

The first operation planned for the Pigs was an attack on

British warships at Alexandria, Egypt, scheduled for the night of 25August

1940. The submarine Iride (Lt

Francesco Brunetti) was carry four Pigs clamped to her casing, releasing them

some 4nm ( 9 miles, 7.4km) from the harbour. With the unprotected Pigs aboard,

the submarine could not dive deeper than the Pigs’ maximum tolerance c.l00ft

(30m ), which would certainly have put her at risk from aircraft patrolling the

clear coastal waters. In the event, Iride

was caught the surface while training for the mission in the Gulf of Bornba,

off Libya, and sunk by torpedo‑planes from HMS Eagle. Among the survivors were Tesei and Toschi, who had both

volunteered for the first combat mission of their weapon.

Meanwhile, thought had been given to the safety of the

mother boats on Pig missions. Beginning in August‑September 1940, five fleet

submarines were fitted with watertight steel cylinders to house Pigs in

transit. The “Perla” class boat Ambra

and the “Adua” class Gondar

and Scire, with the forward 3.9in

(99mm ) gun removed, mounted one cylinder forward and two aft; the “Flutto”

class Grongo and Murena, completed in 1943, were both designed to mount four

cylinders on the side casing, one pair just fore and aft the conning tower on

either side. The Pigs could be taken from their cylinders by crewmen in “frogman”

outfits (I employ the term for convenience; it was not in use in 1940‑41) and

mounted by their operators while the mother boat lay submerged.

One of the mother boats was soon lost. Late in September

1940, Gondar and Scire ( the former commanded by Lt Brunetti, who had survived hide’s sinking) sailed to launch

simultaneous Pig strikes against Alexandria and Gibraltar respectively. The

missions were aborted when intelligence reported the absence of major warships

at both anchorages, but on the homeward run Gondar

was intercepted by the destroyers HMS Diamond

and HMAS Stuart, supported by

Short Sunderland flying‑boats. Badly damaged by depth charges after a 12‑hour

hunt, Gondar surfaced and was

scuttled by her crew. Among those taken prisoner were Capt Toschi, co‑inventor

of the Pig, and Cdr Mario Giorgini, commanding 1st Light Flotilla. Giorgini’s

place was taken by Cdr Vittorio Moccagatta, under whom the “special

weapons” section took the name by which it is best known: Decima Flottiglia MAS, 10th Light

Flotilla.)

The nearest approach to operational success during the first

year of manned‑torpedo operations was made by Pigs launched from Scire (Cdr Borghese ) in Algeciras Bay,

Gibraltar, on the night of 29‑30 October 1940. One of the three Pigs launched

sank within 30 minutes. A second, piloted by the now Major Tesei, with Sgt‑Diver

Alcide Pedretti, reached the mouth of the inner harbour before failure of both

men’s breathing‑apparatus, and of the reserve set, caused Tesei to abort the

mission. Scuttling their craft (the eventual fate of which is described on page

220) Tesei and Pedretti swam to the Spanish shore where, like the crew of the

other sunken Pig, they were able to contact Italian agents and return safely to

Italy.

The third Pig, crewed by Lt Gino Birindelli and PO‑Diver

Damos Paccagnini, although handling sluggishly because of a faulty trimming

tank, penetrated the military harbour while running just awash, surfaced fully

to clear the boom defences, and at last crept along the harbour bottom at

c.50ft (15m) towards the battleship HMS Barham.

Within about 75yds ( 70m ) of this rich prize, the Pig’s motor failed:

Birindelli, single‑handed because Paccagnini’s breathing‑gear had failed,

attempted to drag the warhead along the harbour bottom towards the battleship.

After some 30 minutes, increasing symptoms of carbon‑dioxide poisoning forced

him to abandon the Herculean task. Setting the time‑fuze (the charge later

exploded harmlessly), Birindelli swam

ashore and, like Paccagnini, was taken prisoner.

Scire returned to

Gibraltar on the night of 26‑27 May 1941, launching three Pigs. One sank;

the others reached merchant shipping anchored in deep water outside the

military harbour but failed to carry through their attacks because of mechanical

failures. Within a few weeks, Tesei was to meet his suicidal end on a Pig at

Malta and, with Toschi a PoW, neither of the Pig’s inventors would take part in

its long‑delayed operational success. Indeed, I would suggest that the suicidal

determination displayed by Tesei at Malta was largely provoked by the Pigs’

poor operational record to date.

Date: 19‑20 September

1941

Place: Algeciras Bay,

Gibraltar

Attack by: Italian

“Maiali” manned‑torpedoes

Target: Allied

shipping at anchor

That record was now to improve dramatically. On the night of

19 September 1941, Borghese took Scire yet

again into Algeciras Bay, releasing three Pigs at its northern end for the run‑down

of some 3nm 3.5 miles, 5.5km ) with the current to the military harbour on the

southeast of the Bay. The Pigs left Scire

at 0100 on 20 September. Italian intelligence reported the presence of a

battleship, an aircraft carrier and two cruisers in the military harbour and

these were, of course, the assigned targets. But the British were by now well

apprised of the Italian threat: the Algeciras roadstead and the entrance to the

military harbour were intensively patrolled by launches which dropped depth

charges at regular intervals.

As it approached the entrance to the military anchorage,

well protected by booms and netting, the Pig crewed by Lt Decio Catalano with

PO‑Diver Giuseppe Giannoni was tracked by a launch. Alternately surfacing and

submerging while dodging between merchantmen anchored in the roadstead,

Catalano at last evaded the hunter but by 0350 he had been driven far from the

harbour entrance. With dawn approaching, he decided on a merchantman as his

target, and he and Giannoni had already fixed their warhead to a sizeable ship

when they discovered that she was a captured vessel of Italian registration.

Quixotically, they unshipped their charge and transferred it to the nearby

armed motorship Durham (10,900 tons,

11075 tonnes, fixing magnetic clamps to the target’s bilge keel and slinging

the warhead beneath it by means of a rope passed through the suspension‑ring on

its upper side, with the fuze on a four‑hour delay. At c.0600, after setting the self‑destruction charge that was now part

of the Pig’s design, Catalano and

Giannoni scuttled their craft and swam to safety on the Spanish shore,

whence they were able to observe the detonation of their warhead at 0916. Badly damaged, Durham was beached by harbour tugs.

Allied patrols had also driven the Pig of Lt Amadeo Vesco

and PO‑Diver Antonio Zozzoli away from the entrance to the military harbour‑and

they, too, had chosen a target in the roadstead. At c.0800, as Vesco and

Zozzoli watched from a Spanish coastguard station, the warhead they had fixed

in place broke in half the small tanker Fiona

Shell ( 2,444 tons, 2483 tonnes).

It was left to Lt Licio Visintini and PO‑Diver Giovanni

Magro to show that the Pig was truly capable of the task for which it was

intended‑the penetration of a heavily‑defended anchorage and the destruction of

shipping therein. After dodging patrolling launches, Visintini submerged to

c.35ft (l lm) to thread his Pig between the steel cables supporting netting

across the mouth of the military harbour. Inside, he surfaced near a British

cruiser. Deciding that he had insufficient time‑it was now 0405‑to penetrate

the harbour more deeply in search of HMS Ark

Royal, his assigned target, Visintini decided against the cruiser in favour

of a large tanker riding low in the water nearby, hoping to start an oil fire

that would engulf the harbour. Submerged to 23ft (7m) below the tanker, and more

than once shocked by depth charge detonations that flung them against its hull,

Visintini and Magro fixed their charge by 0440, remounted their Pig, and again

evaded the patrols to make a clean getaway. By 0630 they were in the hands of Italian

agents in Spain, disappointed only in that when a violent explosion broke the

back of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary oiler Denbydale

(8,145 tons, 8275 tonnes) at 0843, the holocaust they had hoped for did not

follow.

The genesis and development of the Pig, its early failures and its first successful mission have been described in sufficient detail to enable the reader to compare the Italian manned‑torpedo with the Japanese and German weapons, suicidal and semi‑suicidal, of the same “family” which are treated of later.

Triumph at Alexandria

Had the Italian naval general staff proved more resolute,

and their German opposite numbers more supportive of an ally, the Pigs’

greatest success might significantly have affected the course of the war. On

the night of 18‑19 December 1941, three Pigs launched from Scire penetrated Alexandria harbour, slipping awash through the

gate in the net‑and‑boom barrier in the wake of British destroyers. Although

special precautionary measures had been ordered only two days before by Admiral

A. B. Cunningham, CinC Mediterranean, the Pigs avoided patrolling launches and

negotiated their targets’ antitorpedo netting while surfaced.

Lt Luigi Durand de La Penne and PO‑Diver Emilio Bianchi were

assigned the battleship HMS Valiant

(30,600 tons, 31090 tonnes). Although Bianchi’s breathing‑gear failed,

forcing him to the surface, and the Pig was immobilized by a fouled propeller,

de La Penne succeeded in manhandling his craft along the bottom for the last

few yards and setting the fuze on its warhead. The two Italians then surfaced

alongside the battleship and were captured. Refusing to respond to questioning,

they were imprisoned in Valiant’s hold,

very near the site of the charge, and were still aboard when detonation

occurred at 0620. A few minutes earlier, the charge placed beneath Valiant’s sister‑ship HMS Queen Elizabeth by Engineer‑Capt Antonio

Marceglia and PO‑Diver Spartaco Schergat had detonated: Admiral Cunningham

himself, then standing right aft on the battleship’s deck, reported being

“tossed about five feet into the air” by the whiplash of the massive

warship. Marceglia and Schergat were captured ashore three days later.

The third Pig, crewed by Gunner‑Capt Vincenzo Martellotta

and PO‑Diver Mario Marino, had been assigned a laden tanker as target and, in

addition to the Pig’s warhead, the men were equipped with six small calcium‑carbide

incendiary charges. Setting their main charge beneath the tanker Sagona (7,554 tons, 7675 tonnes), the

Italians fuzed their incendiaries to detonate later than the warhead and

released them to float nearby, hoping that an oil fire would be started.

Although this stratagem failed, Sagona and

the destroyer HMS Jervis, moored

alongside, were both severely damaged. Martellotta and Marino were captured

ashore.

Admiral Cunningham ordered the Italian prisoners to be held

incommunicado for six months but this and other disinformation measures almost

certainly failed to prevent the Axis commanders from learning the full extent

of the damage. Valiant, with a 1,800

sq ft (167 sq m) rent in her lower bulge forward and much internal damage, was

out of action until July 1942. Queen

Elizabeth was worse hit: with her double bottom stove in over an area of

5,400 sq ft (502 sq m) and serious damage to her machinery, she settled on the

harbour bottom. An attempt to finish her off by Pigs launched from Ambra on 14 May 1942 failed; she was

patched up and dispatched to the United States for permanent repairs, which

were not completed until June 1943.

Cunningham praised “the cold‑blooded bravery and

enterprise of these Italians” and rated the damage to the battleships

“a disaster”. Ordering the construction of far heavier barriers at

the harbour entrance, he commented that after the attack “everyone has had

the jitters, seeing objects swimming about at night . . . That must stop”.

One immediate counter‑measure was to order warships at anchor to keep their

engines running slow astern: the wash thus created beneath the hull would, it

was thought, “flush out” enemy swimmers or at least hinder their

nocturnal activities.

For the expenditure of three Pigs and six men captured, the

10th Light Flotilla had reversed the balance of naval power in the

Mediterranean, but the Italian high command (subsequently blaming the Germans

for failing to provide an adequate fuel supply for increased naval operations)

did not take full advantage of this sudden superiority in capital ships.

Pigs and “Gamma Groups”

In mid‑1942, Borghese became commander of the 10th Light

Flotilla, handing over Scire to Cdr Bruno Zelik (who was lost with all his crew

on 10 August 1942 when the submarine was sunk by the AS‑trawler HMS Islay while

attempting to launch Pigs off Haifa harbour, Palestine). Under Borghese’s

driving leadership, “special attack” operations flourished.

In late 1941, Borghese had been instrumental in forming the

“Gamma Groups” to operate in conjunction with the Pigs. Originally

intended as “underwater infantry” who would walk the seabed in much

the same way as the Japanese Fukuryu,

the Gamma men soon evolved into assault swimmers. These “frogmen”,

clad in protective rubber suits with swim‑fins on their feet, had self‑contained

breathing‑gear which gave them an underwater endurance of c.30‑40 minutes. Each

man carried on a waist‑belt four or five “bugs”, 4.4‑6.61b (2‑3kg)

time‑fuzed explosive charges, with suction cups by which they were affixed to

enemy hulls. The “bugs” were later replaced by magnetic

“limpets” of 9.91b (4.5kg ), which incorporated both time‑ and

distance‑fuzes; when it was learned that the British had formed an anti‑limpeteer

team of frogmen at Gibraltar under Lt. L.K.P “Buster” Crabb, RN, a

booby‑trap device was added to the Italian swimmers’ charges. A fully‑equipped

Gamma man was expected to operate to a range of up to c.4nm (4.6 miles, 7.4km)

at an average speed of 0.8kt (0.9mph, 1.5kmh ), leaving a mother boat along

with the Pigs, making his approach to the target on the surface, and diving

only for the final run‑in.

The major successes of the combined Pig‑Gamma teams were

scored against Allied shipping at Gibraltar, where an Italian base was established

in Algeciras Bay itself. The Italian freighter Olterra had been sabotaged at the beginning of the war and lay half‑sunken

in Spanish territorial waters. On the pretext of being repaired and handed over

to Spain, she was raised and towed into Algeciras harbour, across the Bay from

the Allied military anchorage. With what must have been the connivance of the

Spanish authorities (although Borghese was to deny this), her hold became the

base for Pigs and Gamma men, who slipped out through an underwater door for a series

of raids on the Algeciras roadstead. Between September 1942 and August 1943,

manned‑torpedoes and swimmers from Olterra

sank or badly damaged 11 Allied merchant ships totalling some 54,200 tons

(55 070 tonnes). In addition, on 12 December 1942, three Pigs and ten Gamma

swimmers were launched from the submarine Ambra (Cdr Mario Arillo) as she lay

submerged in the Algiers roadstead, sinking or damaging four merchantmen

totalling c.22,300 tons (22660 tonnes). At the time of Italy’s collapse, preparations

were being made aboard Olterra to

launch the newly‑received SSB‑type Pig against Gibraltar.

Italo-British Chariot Teams

Late in 1943 the British Chariot teams were reinforced by

those members of the Italian 10th Light Flotilla (MAS), led by Cdr

Ernesto Forza, who had chosen not to follow Borghese in continued adherence to

the Axis cause. A number of operations by Italo-British manned-torpedo teams

and ‘frogmen’ were carried out against units of the Italian fleet that had

fallen into German hands.

On the night of 21-22 June 1944, Pigs and Chariots launched

from the Italian destroyer Grecale and the British MTB 74 penetrated

La Spezia to sink the heavy cruiser Bolzano (11,065 tons, 11242 tonnes);

a few nights later, in a similar attack, the heavy cruiser Gorizia was

badly damaged. In the last manned-torpedo operation in European waters, on the

night of 19-20 April 1945, the uncompleted aircraft carrier Aquila (27,000

tons, 27432 tonnes), which the Germans planned to use as a blockship at Genoa,

was sunk in her dock by Italo-British manned-torpedoes and swimmers.