Causes

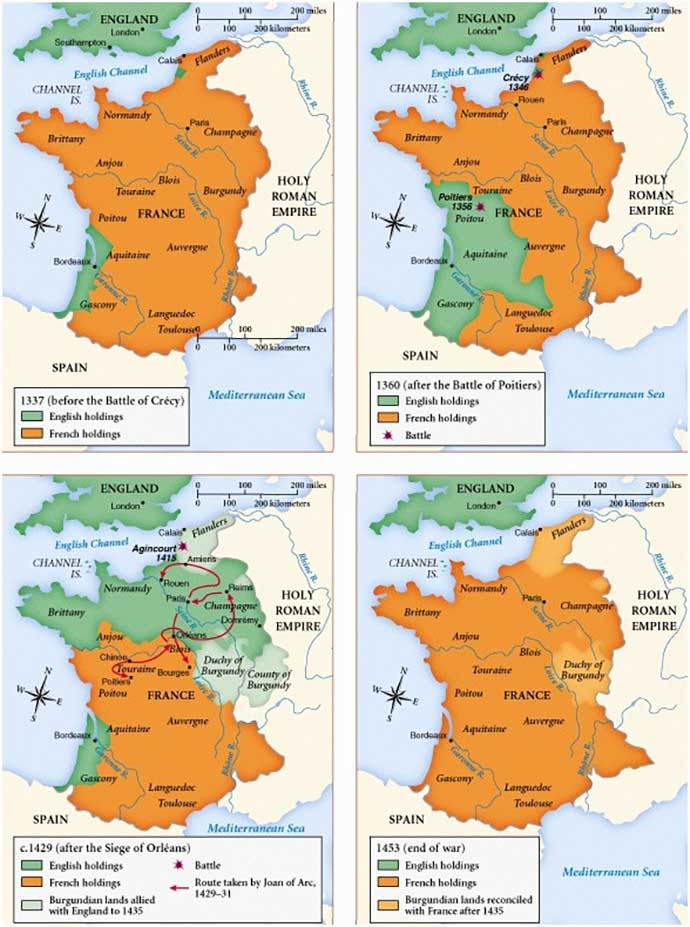

Actually a series of wars, the Hundred Years’ War began in 1337 and lasted until 1453. The chief cause of the war was the desire of the English kings to hold on to and expand their territorial holdings in France, while the French kings sought to “liberate” territory under English control. King Edward III of England (r. 1327- 1377) claimed to have better right to the French throne than did its occupant, King Philip VI (r. 1330-1350). Another factor was the struggle for control both of the seas and international trading markets. Finally, the English sought retribution for the assistance provided by the French to the Scots in their wars with the English.

In 1328, Philip VI marched in troops and established French administrative control over Flanders, where the weavers were highly dependent on English wool. Edward III responded to Philip’s move by embargoing English wool in 1336. This led to a revolt of the Flemings against the French and their conclusion of an alliance with England in 1338. Edward III then declared himself king of France, and the Flemings recognized him as their king. Philip VI declared Edward’s fiefs in France south of the Loire forfeit and in 1338 sent his troops into Guienne (Aquitaine). The war was on.

Course

The first phase of the war lasted from 1337 to 1396. It began with Edward dispatching raiding parties from England and Flanders to attack northern and northeastern France. In 1339 Edward invaded northern France but then withdrew before Philip’s much larger army. Philip planned to turn the tables and invade England, ending Edward’s claim to the French throne. Toward that end, French admiral Hughes Quiéret assembled some 200 ships, including 4 Genoese galleys, off the Flemish coast.

Already planning another invasion of France to secure the French throne, Edward III gathered some 200 ships at Harwich. Warned of the French invasion force assembly, Edward planned to strike first.

The English fleet sailed from Harwich on June 22, with Edward commanding in person, and arrived off the Flanders coast the next day. Fifty additional ships joined it, and Edward sent men and horses ashore to reconnoiter. The reconnaissance completed, he decided to attack the next day.

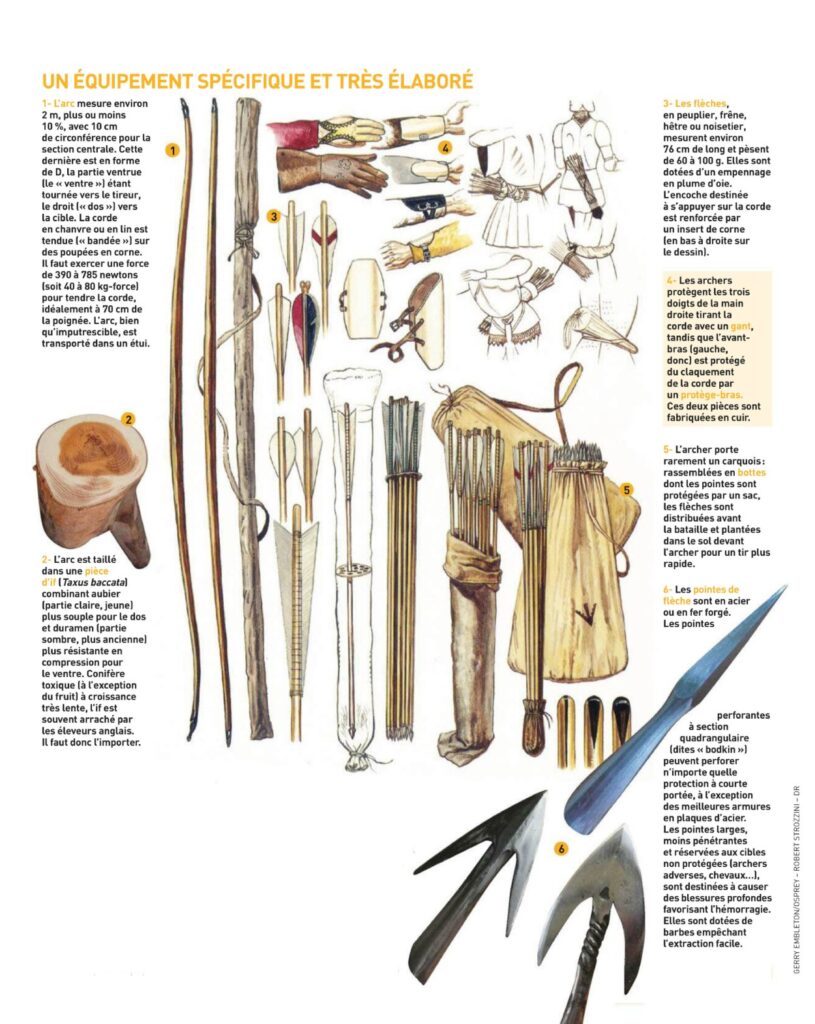

Sea battles of that day resembled fights on land and were decided at close range, often by boarding. Ships were virtually movable fortresses with temporary wooden structures known as castles added at bow (the origin of the term “forecastle”) and stern of converted merchant ships in order to give a height advantage for bow- men or allow the opportunity to hurl down missiles against an opposing ship’s crew. It has been claimed but not proven that some of the ships in the battle carried primitive cannon as well as catapults.

The battle occurred off Sluys (Sluis, Ecluse) on the Flemish coast. Quiéret had divided his 200 ships into three divisions. He ordered the ships of each division chained together side by side, with each ship having a small boat filled with stones triced up in the mast so that men in the tops could hurl missiles down on the English decks. The French were armed chiefly with swords and pikes but had little in the way of armor. Quiéret also had some crossbowmen. In effect, he planned to face the English with three large floating forts incapable of rapid movement. Estimates of the number of Frenchmen involved range from 25,000 to 40,000.

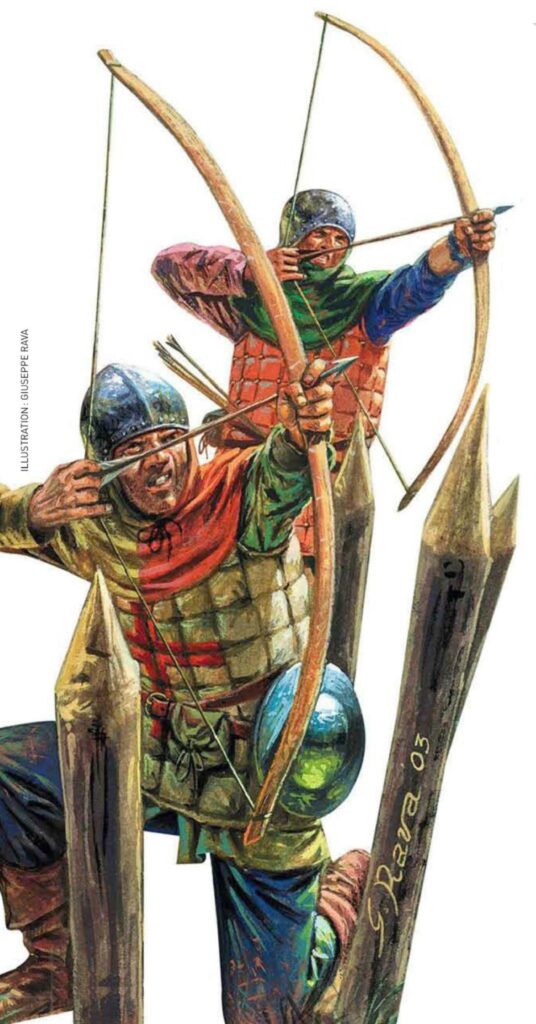

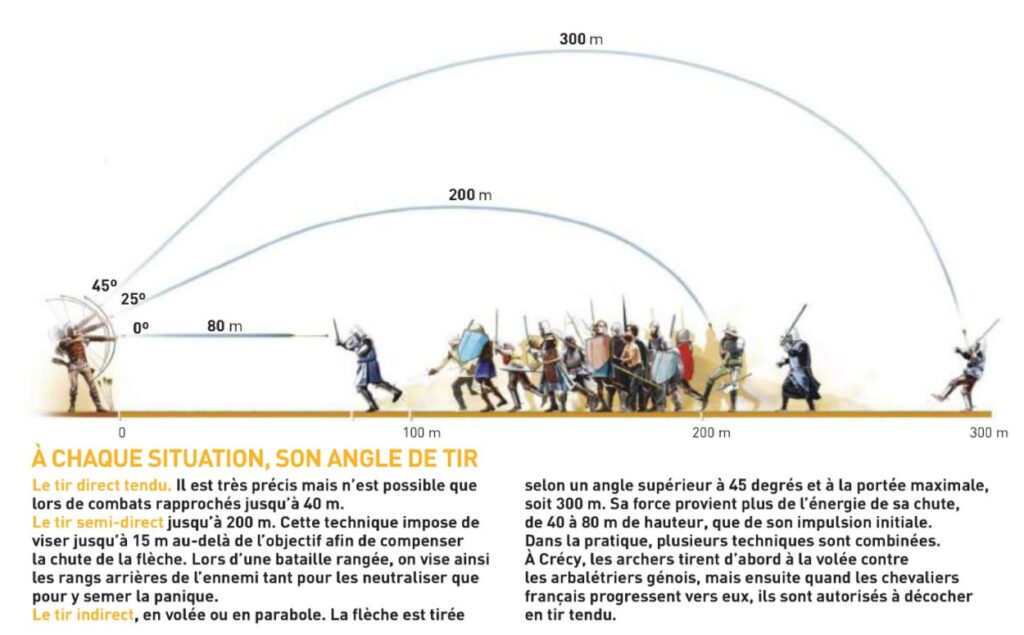

Edward had many archers and men-at- arms, the latter well armored. He placed the largest of his 250 ships in the van, and between every 2 ships filled with archers, he placed ships filled with men-at-arms. The smaller ships formed a second division with archers. The decisive weapon in this battle, as it would be on land, was the longbow, which outranged the crossbow.

Barbavera, the commander of the Genoese galleys in the French fleet, urged that they put to sea. He pointed out that failure to do so would yield to the English the advantages of wind, tide, and sun. Quiéret rejected this sound advice.

The Battle of Sluys opened at about noon on June 24, 1340. The English archers poured volley after volley of arrows into the French ships. Once they grappled a French vessel, the Englishmen boarded it and cleared its decks in hand-to-hand fighting. They then proceeded to the next ship, taking one after another under a protective hail of arrows.

Having secured the first division of French ships, the English moved on to the other two divisions. The action extended into the night. The French fleet was almost annihilated, with the English sinking or capturing 166 of their 200 ships. Estimates of casualties vary widely, but the French and their allies may have lost as many as 25,000 men killed, Quiéret among them. The English lost 4,000 men. Edward III now claimed the title “Sovereign of the Narrow Seas.” His letter to his son about the battle is the earliest extant English naval dispatch.

The Battle of Sluys was the most important naval engagement of the Hundred Years’ War, giving England command of the English Channel for a generation and making possible the invasion of France and the English victories on land that followed. Without the Battle of Sluys, it is unlikely that the war between England and France would have lasted long.

Edward then landed troops and besieged Tournai, but the French forced him to raise the siege and conclude a truce that same year. During 1341-1346 a dynastic struggle occurred in Brittany in which both Edward and Philip VI intervened. To raise money, Philip had introduced the gabelle (salt tax), which led to increased dissatisfaction with his rule. In 1345 Edward began to raise an expeditionary force to invade Normandy, intending to assist his allies in Flanders and Brittany.

Edward landed at La Hogue near Cherbourg in mid-June with perhaps 15,000 men, including a heavy cavalry force of 3,900 knights and men-at-arms and a large number of archers. Most were veterans of the Scottish wars. Edward’s army in France was experienced, well trained, and well organized; it was probably the most effective military force for its size in all Europe.

The fleet returned to England, and Edward marched inland. The English took Caen on July 27 following heavy resistance. Edward ordered the entire population killed and the town burned. Although he later rescinded the order, perhaps 3,000 townsmen died during a three-day sack of Caen. This act set the tone for much of the war.

Edward III then moved northeastward, pillaging as he went. For the next month, Philip chased Edward across northern France without bringing him to battle. Meanwhile, Philip’s son, Duke John of Normandy, moved north against the English from Gascony, while Philip assembled another force near Paris. Edward III thus achieved his aim of drawing pressure from Guyenne and Brittany.

Reaching the Seine at Rouen, Edward learned that the French had destroyed all accessible bridges over that river except one at Rouen, which was strongly de- fended. Increasingly worried that he might be cut off and forced to fight south of the Seine, Edward moved his army rapidly along the riverbank southeast and upriver toward Paris, seeking a crossing point that would allow a retreat into Flanders if need be. At Poissy only a few miles from Paris, the English found a repairable bridge and, on August 16, crossed over the Seine there. Although Philip VI had a sizable force at St. Denis, he made no effort to intercept him.

Only after the English had crossed the Seine and were headed north did Philip attempt to intercept. Edward reached the Somme River on August 22, about a day ahead of the pursuing Philip, only to learn that the French had destroyed all the bridges over that river except those at heavily fortified cities. After vainly attacking both Hangest and Pont-Remy, Edward moved north along the western bank trying to find a crossing. On August 23 at Ouisemont, the English killed all the French defenders and burned the town.

On the evening of August 24 the English camped at Acheux. Six miles distant, a large French force defended the bridge at Abbeville, but that night the English learned of a ford only 10 miles from the coast that could be crossed at low tide and was likely to be undefended. Breaking camp in the middle of the night, Edward moved to the ford, named Blanchetaque, only to discover that it was held by some 3,500 Frenchmen under experienced French commander Godemar du Foy.

A now desperate supply situation and the closeness of the French army led Edward III to attempt to cross here. Battle was joined at low tide on the morning of August 1. Edward sent some 100 knights and men across the ford under the cover of a hail of arrows from his longbowmen. The English gained the opposite bank and were able to establish a small beachhead. Edward then fed in more men, and under heavy English longbow fire, the French broke and fled toward Abbeville. Soon the entire English army was across. So confident was Philip VI that the English would not be able to cross the Somme that no effort had been made to clear the area on the east bank of resources, and the English were thus able to resupply, burning the towns of Noyelles-sur-Mer and Le Crotoy in the process.

Finally, having resupplied and reached a position where he could withdraw into Flanders if need be, Edward III decided to stand and fight. On August 25 he selected a defensive position near the village of Crécy-en-Ponthieu. High ground overlooked a gentle slope over which the French would have to advance. The English right was anchored by the Maye River. The left, just in front of the village of Wadicourt, was protected by a great wood 4 miles deep and 10 miles long.

Edward III commanded more than 11,000 men. He divided his forces into three divisions, known as “battles.” Each contained a solid mass of dismounted men- at-arms, perhaps six ranks deep and about 250 yards in length. Edward positioned two of the “battles” side by side as the front line of his defense. The 16-year-old Ed- ward, Prince of Wales (later known as the “Black Prince”), had nominal command of the English right, although Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick, held actual command. The Earls of Arundel and Northampton commanded the left “battle.” The third “battle,” under Edward’s personal command, formed a reserve several hundred yards to the rear. Archers occupied the spaces between the “battles” and were echeloned forward in V formations pointing toward the enemy so as to deliver enfilading fire.

Edward located a detachment of cavalry to the rear of each “battle” to counterattack if need be. He also had his men dig holes on the slope as traps for the French cavalry. The king used a windmill located between his own position and his son’s right “battle” as an observation post during the battle.

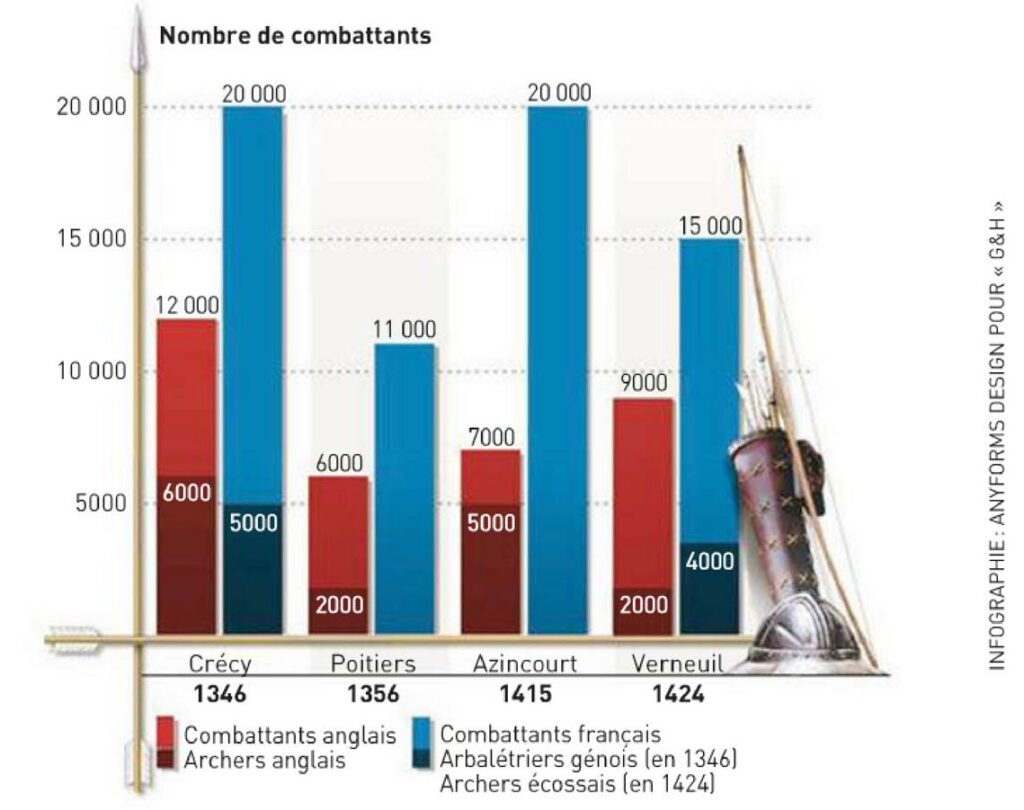

It has been suggested that Edward may have had some gunpowder artillery at Crécy, but that is by no means certain. The year before he had ordered 100 ribaulds, light guns mounted on carts. If these were employed in the battle, it was the first European land battle for gunpowder artillery. In any case, they did not influence the outcome. The French army at Crécy has been variously estimated at between 30,000 and 60,000 men, including 12,000 heavy cavalry of knights and men-at-arms, 6,000 Genoese mercenary crossbowmen, and a large number of poorly trained infantry. This French force, moving without a reconnaissance screen or any real order, arrived at Crécy at about 6:00 p. m. on August 26, 1346. Without bothering to explore the English position, Philip VI attempted to organize his men for battle. He positioned the Genoese, his only professional force, in a line in front. At this point a quick thunderstorm swept the field, rendering the ground slippery for the attackers.

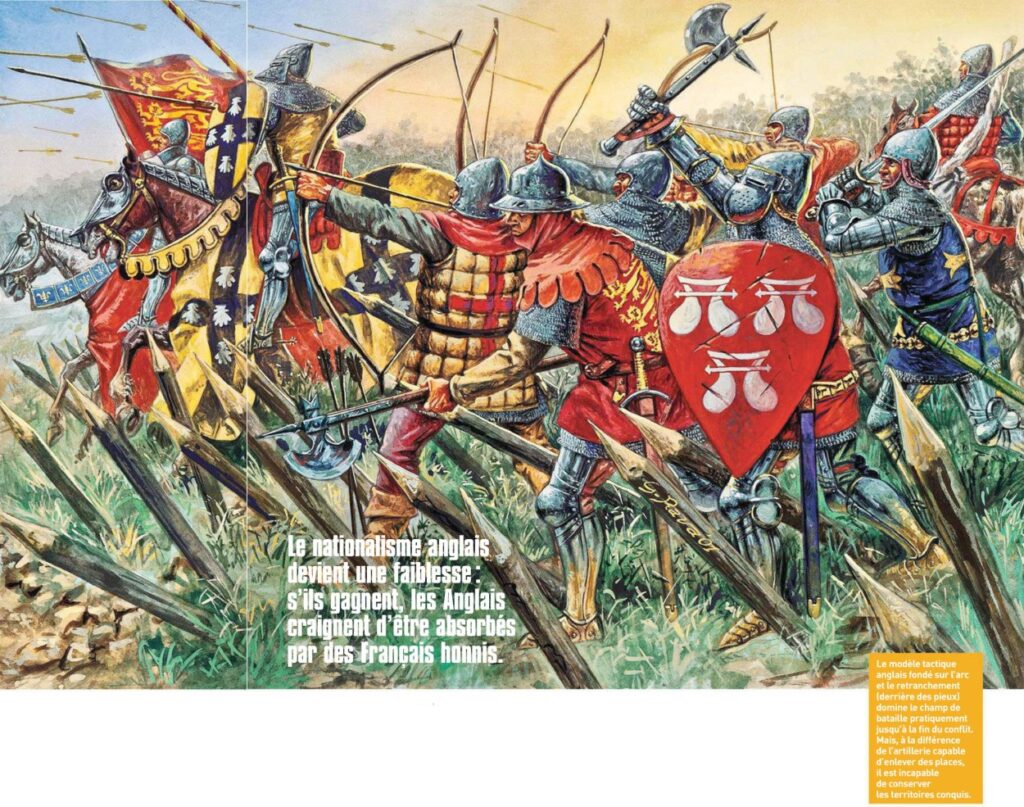

The well-disciplined Genoese moved across the valley toward the English position, with the disorganized French heavy cavalry in a great mass behind them. Halting about 150 yards from the English “battles,” the Genoese loosed their crossbow bolts, most of which fell short. They then reloaded and began to move forward again, only to encounter clouds of English arrows. The Genoese could fire their crossbows about one to two times a minute, while the English longbowmen could get off an arrow every five seconds. The English arrows completely shattered the Genoese, who were not able to close to a range where their crossbow bolts might have been effective.

The French knights behind the Genoese, impatient to join the fray, then rode forward up the slippery slope, over and around the crossbowmen, and encountered the same swarms of arrows. The shock of the French charge carried to the English line, however, where there was some hand-to-hand combat. The English cavalry then charged, and the remaining French knights were driven back. The French regrouped and repeatedly charged (the English claimed some 15-16 separate attacks throughout the night), each time encountering English arrows before finally breaking off contact. The battle was over. The French dead included some 1,500 knights and men-at-arms and between 10,000 and 20,000 crossbowmen and infantrymen in addition to thousands of horses. Philip VI was among the many Frenchmen wounded. English losses were only about 200 dead or wounded.

Crécy made the English a military nation. Europeans were unaware of the advances made by the English military system and were stunned at this infantry victory over a numerically superior force that included some of the finest cavalry in Europe. Crécy restored the infantry to first place. Since this battle, infantry have been the primary element of ground com- bat forces.

After several days of rest, Edward III marched to the English Channel port of Calais and, beginning on September 4, commenced what would be a long siege. Only in July 1347 did Philip VI make a halfhearted attempt to relieve Calais. The city fell on August 4. It turned out to be the sole English territorial gain of the campaign, actually of the entire Hundred Years’ War. On September 28, 1347, the two sides concluded a truce that, under the impact of the plague known as the Black Death, lasted until 1354.

With the failure of negotiations for a permanent settlement, fighting resumed in 1355. The English mounted a series of devastating raids. King Edward III struck across the English Channel into northern France, his son Edward the Black Prince moved from Bordeaux into Languedoc, and Edward’s second son John of Gaunt attacked from Brittany into Normandy.

The English did not seek battle with the far larger French army; their intent was simply to plunder and destroy. Edward III landed in France to strengthen the northern force but was forced to return to England on news that the Scots had taken Berwick. John was unable to cross the Loire and effect a juncture with his brother’s force.

Edward the Black Prince had set out from Bergerac on August 4. Most of his men were from Aquitaine, except for a number of English longbowmen. He reached Tours on September 3 and there learned that French king John II (the Good, r. 1350-1364) and as many as 35,000 men had crossed the Loire at Blois on September 8. As he had only about 8,000 men, the Black Prince ordered a rapid withdrawal down the road to Bordeaux, but the English were slowed by their loot. The French succeeded in cutting off the raiders and reached Poitiers first, making contact on September 17 at La Chabotrie. The prince did not want to fight, but he realized that his exhausted men could go no farther without having to abandon their plunder, and he cast about for a suitable defensive position, moving to the village of Maupertuis some seven miles southeast of Poitiers.

John II wanted to attack the English on the morning of September 18, but papal envoy Cardinal Hélie de Talleyrand-Périgord persuaded him to try negotiations. The Black Prince offered to return towns and castles captured during his raid along with all his prisoners, to promise not to do battle with the French king for seven years, and to pay a large sum of money, but John II demanded the unconditional surrender of the prince and 100 English knights.

Edward refused. He had selected an excellent defensive site, and his men used the time spent in negotiations to improve their positions. Edward’s left flank was protected by a creek and a marsh. Most of his archers were on the flanks, and his small cavalry reserve was on the exposed right flank.

John II’s army greatly outnumbered his opponent. It included 8,000 mounted men-at-arms, 8,000 light cavalry, 4,500 professional mercenary infantry (many of them Genoese crossbowmen), and perhaps 15,000 untrained citizen militia. Rejecting advice to use his superior numbers to surround the English and starve them out or turn the English position, the king decided on a frontal assault. He organized his men into four “battles” of up to 10,000 men each. The men-at-arms in the French “battles” were to march the mile to the English lines in full armor.

The resulting Battle of Poitiers on September 19, 1356, was a repeat of the August 1346 Battle of Crécy. The footmen in the first French “battle” who had not fallen prey to English arrows reached the English defensive line at a hedge. The next French division, under the Dauphin Charles, moved forward and there was desperate fighting, with the French al- most breaking through. Edward commit- ted everything except a final reserve of 400 men, and the line held. The remaining French reeled back. The English were now in desperate straits, and if the next French “battle” commanded by the Duc d’Orléans, the brother of the king, had advanced promptly to support their fellows or struck the exposed English right flank, the French would have won a great victory. Instead, on seeing the repulse of their fellows it withdrew from the field with them.

This produced a slight respite for the defenders to reorganize before the arrival of the last and largest French “battle” of some 6,000 men, led by John II in person. The French were exhausted by the long march in full armor, but the English were also at the end of their tether. Fearing that his men could not withstand another assault, the Black Prince ordered his cavalry and infantry, along with the archers who had used up their arrows, to charge the French. He also sent about 200 horsemen around to attack the French rear. Desperate fighting ensued in which John II wielded a great battle-ax.

The issue remained in doubt until the English cavalry struck the French rear. The French then fled; the English were too exhausted to pursue. “There were slain all the flower of France,” says Jean Froissart in his chronicles. The French suffered perhaps 2,500 dead and a like number of prisoners, including King John II, his 14-year-old son Philip, and two of his brothers, along with a multitude of the French nobility, including 17 counts. The English may have sustained 1,000 killed and at least as many wounded.

Following the battle, the Black Prince withdrew to Bordeaux with both his booty and prisoners. Vast fortunes were made over the ransoming of the nobles. Meanwhile, there was chaos in France with the collapse of the central government.

The next 10 years saw the English raiding the French countryside almost at will, as did bands of freebooters known as routiers. Those French who could do so sought refuge in castles and fortified cities. In 1358 the peasants, who had been unable to defend themselves against their many attackers, rose up against the nobles in what is known as the Jacquerie. It was prompted by the heavy taxes levied on the peasants to pay for the war against England and the ransom of nobles taken in the Battle of Poitiers but also by anger regarding the pillaging of the countryside by the routiers. The Jacquerie was crushed by the nobles, led by Charles the Bad of Navarre.

In 1360 the Dauphin Charles signed the Treaty of Brétigny, ransoming John II in return for 3 million gold crowns. While Edward III gave up any claim to the throne of France, he received Guyenne in full sovereignty as well as the Limousin, Poitou, the Angoumois, the Saintonge, Rouerque, Ponthieu, and other areas. King Edward now possessed an independent Guyenne but also Aquitaine, representing one-third of the area of France. Edward set up the Black Prince at Bordeaux as the duke of Aquitaine.

John II was allowed to return home from England, but his three sons remained behind as hostages until the ransom was paid. When one son escaped, the good king returned of his own free will to take his place, dying in England in 1364. Incredibly, the lessons of the Battle of Poitiers seem not to have taken, it being said that the French remembered everything but learned nothing. Poitiers would be virtually replicated in form and effect at Agincourt in 1415.

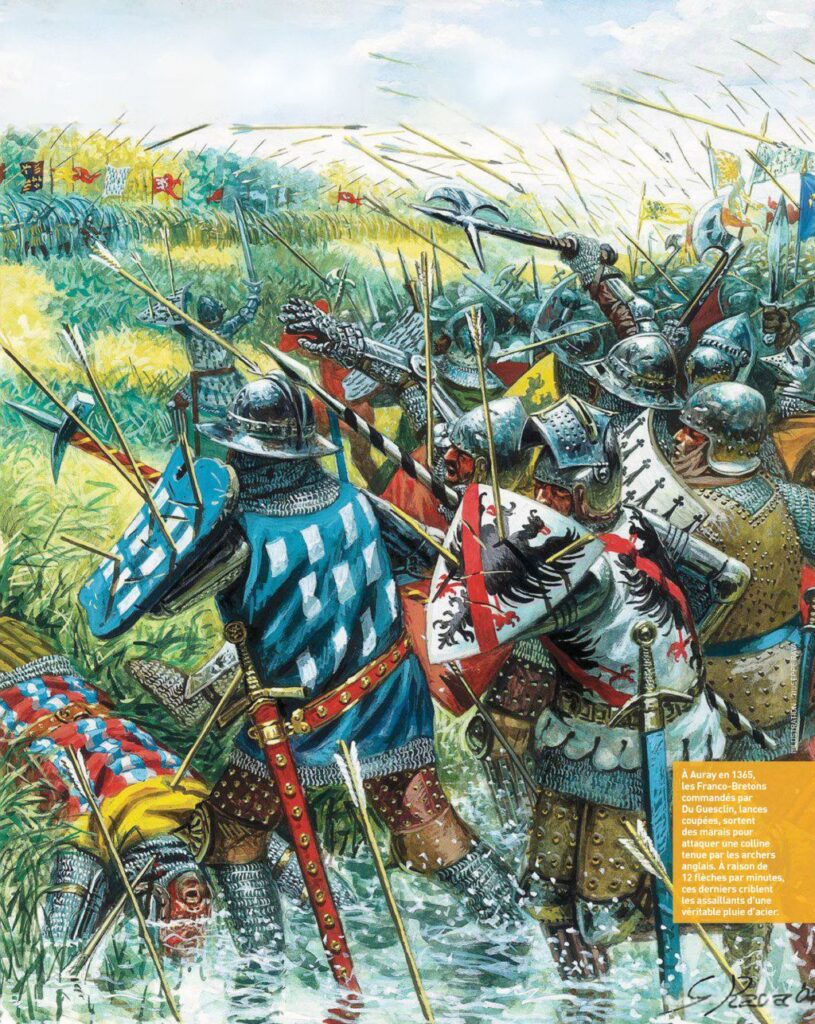

Nominal peace was maintained from 1360 to 1368, although fighting continued in the successionist struggle in Brittany. There in 1364 the English drove off a French army attempting to relieve their siege of Auray and went on to take the town. Charles the Bad, ruler of Navarre, took advantage of French weakness to seize territory in southwestern France.

In 1364 King Charles V came to the French throne. Known to French history as Charles the Wise, he was physically weak yet an able realist. He was probably responsible for saving France, rescuing it from the military defeats and chaos that occurred under his immediate predecessors Philip VI and John II. With the able assistance of the first great French military commander of the Hundred Years’ War, constable of France Bertrand du Guesclin, Charles reformed the French military.

The two men created new military units and established the French artillery, along with a permanent military staff. They also reorganized the navy and ordered the rebuilding of castles and city walls (most notably in Paris). In addition, Charles managed to control the new financial arrangements established by the States General. In 1364, he dispatched du Guesclin and French troops to intervene in the civil war in Castilla (Castile).

In 1368 a revolt by the nobles of Gascony against Edward the Black Prince, Duke of Aquitaine, provided Charles the opportunity to test his new military. The French military intervention in Gascony, however, led King Edward III of England to again lay claim to the French throne.

Adopting a commonsense approach to warfare, du Guesclin employed such techniques as night attacks (despite English charges that these were unknightly). He also excelled in siege warfare, and one by one he captured castles held by the English. In 1370, however, Edward the Black Prince took and sacked the French city of Limoges, massacring many of its inhabitants.

The reformed French Navy met success when, off the southwest coast of France on June 22-23, 1372, some 60 Castilian and French ships under Genoese admiral Ambrosio Bocanegra defeated an English fleet of 40 ships under John of Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, sent to relieve the French siege of English-held La Rochelle. The allies captured Pembroke, along with 400 English knights and 8,000 soldiers. This naval victory also gave the French control of the western French coast and of the English Channel for the first time since the Battle of Sluys in 1340.

In 1375 a formal truce went into effect between the two sides, lasting until 1383, although sporadic fighting continued. The principal figures in the war died during this period: Edward the Black Prince in 1376; his father, King Edward III of England, in 1377; Constable of France du Guesclin in 1380; and French king Charles V in 1380.

Richard II was only 10 years old when he became king of England in 1377. His uncle, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, exercised power as regent. The government was nearly overthrown in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 led by Jack Straw and Wat Tyler. Then rebels under Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, defeated the royalists in the Battle of Radcot Bridge in 1387 and forced Richard to agree to their demands. Another dispute with his nobles led Richard to assume absolute power in 1397, producing yet another revolt and his forced abdication.

In 1386 the French began preparations for an invasion of England, but the plan was abandoned following an English naval victory in the Battle of Margate (March 24, 1387), when the English captured or destroyed some 100 French and Castilian ships. Another period of truce ensued during 1389-1396, nonetheless occasionally interrupted by fighting.

In 1396 Kings Richard III of England and Charles VI of France signed the Truce of Paris. Supposed to last 30 years, under it England retained in France only the port of Calais and Gascony in southwestern France between Bordeaux and Bayonne. The truce lasted only until 1415, however, and was, in any case, marked by intermittent warfare. In 1402, moreover, French troops had assisted the Scots in an invasion of England. The English also had to contend with a revolt in Wales during 1402-1409, led by the Prince of Wales Owen Glendower, who waged a highly effective guerrilla campaign against English rule. In 1403 English king Henry IV also faced a revolt of northern nobles led by Henry “Hotspur” Percy, who led some 4,000 men deep into central England with the aim of joining forces under Glendower. Henry, however, interposed his own army between them and defeated Percy in the Battle of Shrewsbury (July 21, 1403) before Glendower could arrive. Percy was among the dead.

With Henry IV preoccupied with these internal revolts, that same year the French raided the southern English coast, including Plymouth. In 1405 the French also landed troops to assist Glendower, but these accomplished little and were soon withdrawn. In 1406 the French mounted operations against English possessions in France, around Vienne and in Calais. In 1408 Hotspur Percy’s father, Henry Percy, first Earl of Northumberland, rebelled against Henry IV but was slain in the Battle of Bramham Moor (February 19). The next year, 1409, Henry also defeated the revolt in Wales.

Louis, Duc d’Orléans, younger brother of French king Charles VI, and John I, Duke of Burgundy, had been at odds seeking to fill the power vacuum left by the increasingly mad Charles. Louis’s assassination on November 24, 1407, brought war between the Burgundians and Orléanists, with each side seeking to involve England on its behalf.

In May 1413 new king of England Henry V (r. 1413-1422), seeking to take advantage of the chaos in France, concluded an alliance with Burgundy. Duke John promised neutrality in return for in- creased territory as Henry’s vassal, at the expense of France. In April 1415 Henry V declared war on King Charles VI. Henry crossed the English Channel from Southampton with 12,000 men, landing at the mouth of the Seine on August 10.

On August 13, Henry laid siege to the channel port of Honfleur. Taking it on September 22, he expelled most of its French inhabitants, replacing them with Englishmen. Only the poorest Frenchmen were allowed to remain, and they had to take an oath of allegiance. The siege, disease, and garrison duties, however, reduced Henry V’s army to only about 6,000 men.

For whatever reasons, Henry V decided to march overland from Honfleur to Calais. Moving without baggage or artillery, his army departed on October 6, covering as much as 18 miles a day in difficult conditions caused by heavy rains. The English found one ford after another blocked by French troops, so Henry took the army eastward, up the Somme, to locate a crossing. High water and the French prevented this until he reached Athies, 10 miles west of Péronne, where he located an undefended crossing.

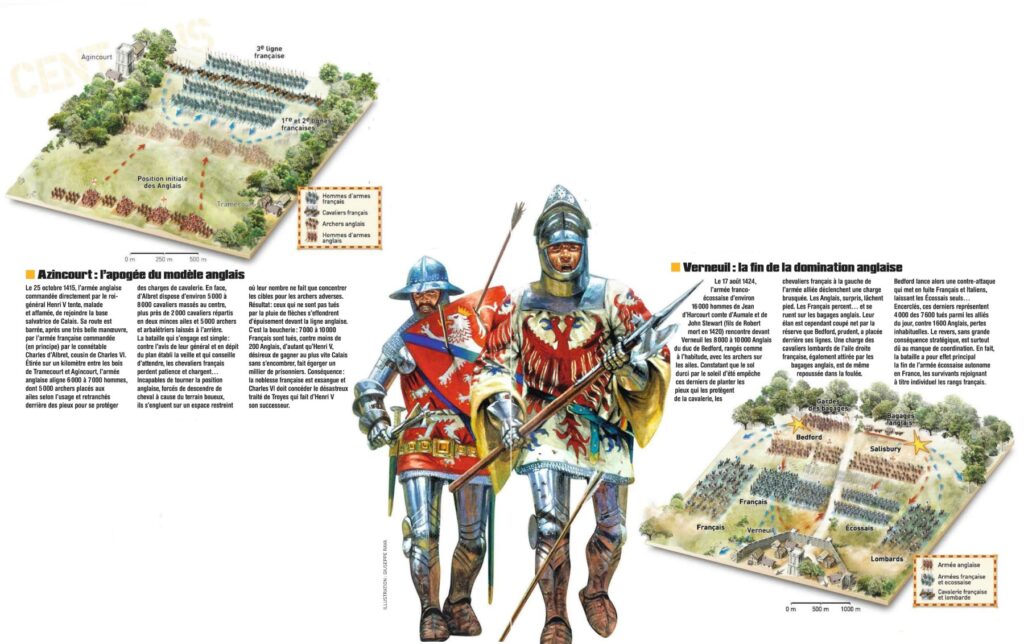

At Rouen the French raised some 30,000 men under Charles d’Albert, constable of France. This force almost intercepted the English before they could get across the Somme. The trail was not hard to find, marked as it was by burning French farmhouses. (Henry once remarked that war without fire was like “sausages without mustard.”)

D’Albert managed to get in front of the English and set up a blocking position on the main road to Calais, near the Chateau of Agincourt, where Henry’s troops met them on October 24. Henry faced an army many times his own in size. His men were short of supplies, and enraged local inhabitants slew English foragers and stragglers. Shaken by his prospects, Henry V ordered his prisoners released and offered to return Honfleur and pay for any damages he had inflicted in return for safe passage to Calais. The French, with a numerical advantage of up to five to one, were in no mood to make concessions. They demanded that Henry V renounce his claims in France to everything except Guyenne, conditions he rejected.

The French nobles were eager to join battle and pressed d’Albert for an attack, but he resisted their demands that day. That night Henry V ordered absolute silence, which the French took as a sign of demoralization. Daybreak on October 25 found the English at one end of a defile about 1,000 yards wide and flanked by heavy woods. The road to Calais ran down its middle. Open fields on either side had been recently plowed and were sodden from the heavy rains.

Drawing on English success in the battles at Crécy and Poitiers, Henry V drew up his 800-1,000 men-at-arms and 5,000 archers in three “battles” of men-at-arms and pikemen in one line. The archers were located between the three and on the flanks, where they enfiladed forward about 100 yards or so to the woods on either side.

About a mile away, d’Albert also deployed in three groups, but because of French numbers and the narrowness of the defile these were one behind the other. The first rank consisted of dismounted men and some crossbowmen, along with perhaps 500 horsemen on the flanks; the second was the same without the horsemen; and the third consisted almost entirely of horsemen.

In the late morning of October 25, with the French having failed to move, Henry staged a cautious advance of about a half mile and then halted, his men taking up the same formation as before, with the leading archers on the flanks only about 300 yards from the first French ranks. The bowmen then pounded sharpened stakes into the ground facing toward the enemy, their tips at breast height of a horse to help protect against mounted attack.

Henry’s movement had the desired effect, for d’Albert was no longer able to resist the demands of his fellow nobles to attack. The mounted knights on either flank moved forward well ahead of the slow-moving and heavily armored men- at-arms. It was Crécy and Poitiers all over again, with the longbow decisive. A large number of horsemen, slowed by the soggy ground, were cut down by English arrows that caught them en enfilade. The remain- der were halted at the English line.

The cavalry attack was defeated long before the first French men-at-arms, led in person by d’Albert, arrived. Their heavy body armor and the mud exhausted the French, but most reached the thin English line and, by sheer weight of numbers, drove it back. The English archers then fell on the closely packed French from the flanks, using swords, axes, and hatchets to cut them down. The unencumbered Englishmen had the advantage, as they could more easily move in the mud around their French opponents. Within minutes, almost all in the first French rank had been killed or captured.

The second French rank then moved forward, but it lacked the confidence and cohesion of the first. Although losses were heavy, many of its number were able to re- tire to re-form for a new attack with the third “battle” of mounted knights. At this point Henry V learned that the French had attacked his baggage train, and he ordered the wholesale slaughter of the French prisoners, fearing that he would not be strong enough to meet attacks from both front and rear. The rear attack, however, turned out to be only a sally from the Chateau of Agincourt by a few men-at-arms and perhaps 600 French peasants.

The English easily repulsed the final French attack, which was not pressed home. Henry then led several hundred mounted men in a charge that dispersed what remained of the French army. The archers than ran forward, killing thousands of the Frenchmen lying on the field by stabbing them through gaps in their armor or bludgeoning them to death.

In less than four hours the English had defeated a force significantly larger than their own. The French lost at least 5,000 dead and another 1,500 taken prisoner. D’Albert was among those who perished. Henry V reported English dead as 13 men- at-arms and 100 footmen, but this is undoubtedly too low. English losses were probably on the order of 300 killed.

Henry V then marched to Calais, taking the prisoners who would be ransomed, and in mid-November he returned to England. The loss of so many prominent French nobles in the Battle of Agincourt greatly increased Duke John of Burgundy’s influence, to the point that he was able to dictate French royal policy.

Henry V spent 1416 preparing his forces and putting together a powerful fleet, which turned back a Genoese effort to control the English Channel. He also secured the neutrality of Holy Roman emperor Sigismund, who had been allied with France. Returning to France in 1417, Henry conducted three campaigns in Normandy during 1417-1419. He success- fully besieged Rouen during September 1418-January 1419 and secured all Normandy, except for the coastal enclave of Mont Saint-Michel.

Duke John of Burgundy was also actively campaigning. On May 29, 1418, his forces captured Paris. Installing him- self there as protector of the insane French king Charles VI, John ordered the massacre of virtually all opposition leaders at court, although the Dauphin Charles managed to escape to the south.

With Duke John controlling Paris and the English having occupied northern France, the Dauphin sought a reconciliation with John. In July 1419 they met on the bridge of Pouilly near Melun. On the grounds that further discussions were re- quired to secure the peace, Charles pro- posed another meeting, on the bridge at Montereay. There on September 10, John appeared with his escort for what he assumed to be negotiations, only to be killed by companions of the Dauphin. In con- sequence, Philip the Good, the new duke of Burgundy, and Isabeau de Baviere (Isabeau of Bavaria), queen consort of France, allied with the English against the Dauphin and his allies, the Orléanists and Armagnacs.

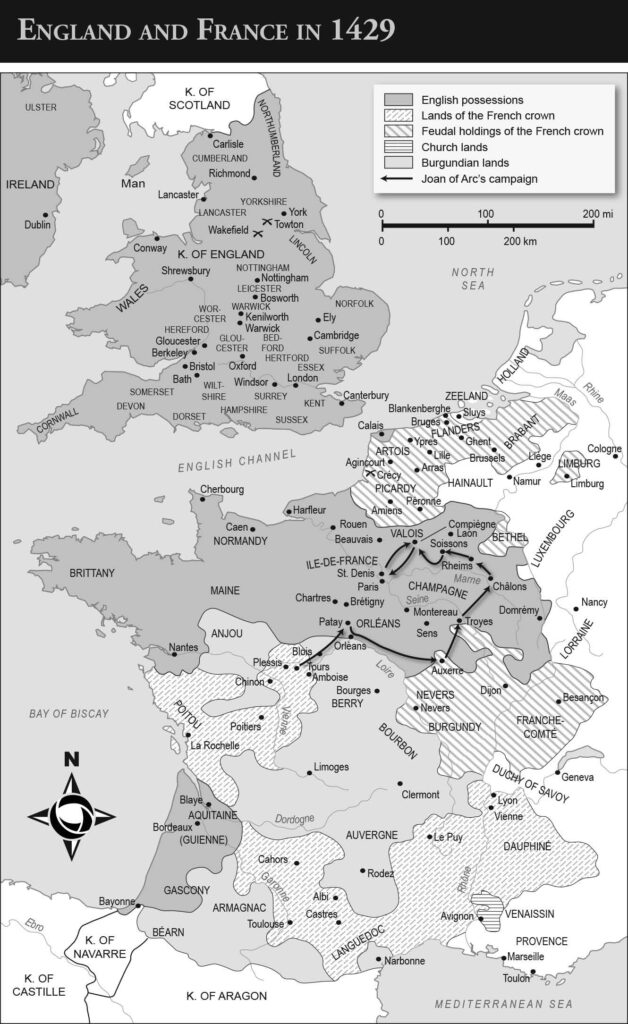

Henry V marched on Paris, forcing French king Charles VI to conclude the Treaty of Troyes on May 21, 1420. Charles agreed to the marriage of Henry to his daughter Catherine. The French king also disowned his son Charles as illegitimate and acknowledged Henry as his legitimate heir. Henry married Catherine of Valois on June 2, 1420, and was now ruler of France in all but name.

With the intention of invading southern France and defeating the Dauphin, Henry first consolidated his hold over French territory north of the Loire. In this connection he successfully besieged Meaux (October 1421-May 1422) but then became ill. On August 31, 1422, Henry V died of dysentery at Blois. The only child of Henry and Catherine, the nine-month-old Henry of Windsor, was crowned king as Henry VI, with Henry V’s brother, John, Duke of Bedford, as regent.

French king Charles VI died in Paris on October 21, 1422. His supporters then crowned at Bruges the Dauphin as King Charles VII. Duke John of Bedford, regent for the boy-king Henry VI, meanwhile continued the English consolidation of northern France, completing it by 1428. Burgundy was increasingly restive in its alliance with England as John prepared to take the offensive against the Dauphin Charles south of the Loire.

In July 1423 a Burgundian-English force of some 4,000 men under Thomas Montacute, fourth Earl of Salisbury, met at Auxerre to intercept a Dauphinist French- Scottish army of 8,000 men under the Comte de Vendome marching into Burgundy for Bourges. The two armies came together on July 31 at Cravant on the banks of the Yonne River, a tributary of the Seine. The Dauphinists were drawn up on the east bank, the Anglo-Burgundians on the west bank. Both were reluctant to attempt a crossing of the shallow Yonne, but after three hours Salisbury ordered his men to ford the waist-deep river, about 50 yards wide. English archers provided covering fire.

A second English force under Lord Willoughby de Eresby forced its way across a narrow bridge and through the Scots, cutting the Dauphinist army in two. The French then collapsed, although the Scots refused to flee and were cut down in large numbers. Reportedly, the French-Scottish army lost 6,000 dead and many prisoners, including Vendome. This battle marked the zenith of English arms in the Hundred Years’ War. The English and Burgundians now anticipated conquering the remainder of France.

In April 1424 John Stewart, second Earl of Buchan, arrived at the Dauphin Charles’s headquarters at Bourges with an additional 6,500 troops from Scotland. In early August the Dauphinist forces departed Tours to join French troops under the Duke of Alençon and the viscounts of Narbonne and Aumale to relieve the castle of Ivry near Le Mans, under siege by the Duke of Bedford. Before the army could arrive, however, Ivry surrendered.

Following a council of war, the Dauphinists decided to attack English strong- holds in southern Normandy beginning with Verneuil, which was secured by a ruse as Scots, pretending to be Englishmen escorting Scottish prisoners, were admitted to the fortified town. Learning what had transpired, John, Duke of Bedford, rushed with English troops to Verneuil.

The Scots persuaded the French to stand and fight, and battle was joined on August 17 about a mile north of Verneuil between 8,000-10,000 Englishmen and 12,000-18,000 French and Scottish troops. The battle was fought along the lines of Crécy and Agincourt, although this time French cavalry broke through. Instead of wheeling about and exploiting this situation, however, they continued on to the north to attack the English baggage train, and the French infantry were then defeated. Bedford had taken the precaution of protecting the baggage train with a strong force of 2,000 longbowmen, and they turned back the cavalry.

The battle was one of the bloodiest of the Hundred Years’ War, but the English emerged victorious, with some 6,000 French and Scottish troops slain. Alençon was captured. The English paid a heavy price, however, with 1,600 of their own dead, far more than at Agincourt. On March 6, 1426, Duke John of Bedford and an English army defeated a French army led by constable of France Arthur de Richemont at St. Jacques near Avranches. The battle forced Jean V, Duc de Brittany, the brother of de Richemont, to submit to the English.

Having consolidated his hold on northern France, Bedford launched a southern offensive. In September 1428 the Earl of Salisbury advanced from Paris with 5,000 men to secure the Loire River crossing at Orléans as the first step to taking the Dauphin’s strong- hold of Armagnac. Orléans was a large city and one of the strongest fortresses in France. Three of its four sides were strongly walled and moated, and its southern side rested on the Loire. The city walls were well defended by numerous catapults and 71 large cannon, and stocks of food had been gathered. Jean Dunois, Comte de Longueville, commanded its garrison of about 2,400 soldiers and 3,000 armed citizens.

Salisbury and his men arrived at Orléans on October 12, 1428, and commenced a siege. Because he had only about 5,000 men, Salisbury was unable to invest Orléans completely. Nonetheless, on October 24 the English seized the fortified bridge across the Loire, although Salisbury was mortally wounded. In December William Pole, Earl of Suffolk, assumed command of siege operations, with the English constructing a number of small forts to protect the bridge and their encampments.

On February 12, 1429, in the Battle of Rouvray, also known as the Battle of the Herrings, an English supply convoy led by Sir John Falstaff transporting a large quantity of salted herrings to the besiegers was attacked by the Comte de Clermont and a considerably larger French force with a small Scottish contingent. Falstaff, who had about 1,000 mounted archers and a small number of men-at-arms, circled his supply wagons. Although greatly outnumbered, the English managed to beat back repeated attacks and then drove off the French.

Although the French in Orléans mounted several forays and were able to secure limited supplies, by early 1429 the situation in the city was becoming desperate, with the defenders close to starvation. Orléans was now the symbol of French resistance and nationalism.

Although the Dauphin Charles was considering flight abroad, the situation was not as bleak as it appeared. French peasants were rising against the English in increasing numbers, and only a leader was lacking. That person appeared in a young illiterate peasant girl named Jeanne d’Arc. Traveling to the French court at Chinon, she informed Charles that she had been sent by God to raise the Siege of Orléans and lead him to Rheims to be crowned king of France.

Following an examination of Jeanne by court and church officials, Charles allowed her, dressed in full armor and with the empty title chef de guerre, to lead a relief army of up to 4,000 men and a convoy of supplies to Orléans. The Duc d’Alençon had actual command. Word of Jeanne and her faith in her divine mission spread far and wide and inspired many Frenchmen.

As the French relief force approached Orléans, Jeanne sent a letter to the Earl of Suffolk demanding surrender. Not surprisingly, he refused. Jeanne then insisted that the relief force circle around and approach the city from the north. The other French leaders finally agreed, and the army was ferried to the north bank of the Loire and entered the city through a north gate on April 29.

Jeanne urged an attack on the English from Orléans, assuring the men of God’s protection. On the morning of May 1 she awoke to learn of a French attack against the English at Fort St. Loup that had begun without her and was not going well. Riding out in full armor, she rallied the attackers to victory. All the English defenders were killed, while the French sustained only two dead. Jeanne then insisted that the soldiers confess their sins and that prostitutes be banned, promising the men that they would be victorious in five days. A new appeal to the English to surrender was met with derisive shouts.

On May 5 Jeanne led in person an attack out the south gate of the city. The French avoided the bridge over the Loire, the southern end of which the English had captured at the beginning of the siege, but crossed through shallow water to an island in the middle of the Loire and from there employed a boat bridge to gain the south bank. They then captured the English fort at St. Jean le Blanc and moved against a large fort at Les Augustins, close to the bridge. The battle was costly to both sides, but Jeanne led a charge that left the French in possession of the fort. The next day, May 6, Jeanne’s troops assaulted Les Tournelles, the towers at the southern end of the bridge. In the fighting Jeanne was hit by an arrow and carried from the field. The wound was not major, and by late afternoon she had insisted on rejoining the battle.

On May 7 a French knight took Jeanne’s banner to lead an attack on the towers. She tried to stop him, but the mere sight of the banner caused the French soldiers to follow it. Jeanne then joined the fray herself. Using scaling ladders, the French assaulted the walls, with Jeanne in the thick of the fight. The 400-500 English defenders attempted to flee by the bridge, but it was soon on fire and collapsed. On May 8 the remaining English forces abandoned the siege and departed.

In his official pronouncements Charles took full credit for the victory, but the French people attributed it to Jeanne and flocked to join her. Although the Hundred Years’ War continued for another two decades, the relief of the Siege of Orléans was the turning point in the long war.

Following their defeat in the Siege of Orléans, the English dispatched an army from Paris under Sir John Falstaff. He joined his men with the remaining English defenders of the Loire battles, and they moved to join battle with the French in the vicinity of the small village of Patay. Falstaff and John Talbot, first Earl of Shrewsbury, had per- haps 5,000 men. French scouts discovered the English at Patay before the latter could complete their defensive preparations. Not waiting for the main body of the army under Jeanne d’Arc to arrive, the French vanguard of some 1,500 cavalry under Étienne de Vignolles, known as La Hire, and Jean Poton de Xaintrailles mounted an immediate charge. Many of the Englishmen with horses were able to escape, but the longbowmen were cut down. Unlike Crécy and Agincourt, for once a French cavalry frontal assault succeeded.

For perhaps 100 French casualties, the English suffered some 2,500 dead, wounded, or taken prisoner. Talbot was among those captured. Falstaff escaped but was blamed for the disaster and disgraced. The battle decimated the corps of seemingly invincible English longbowmen and did much to restore French confidence that they could defeat the English in open battle. The French peasants also took heart and began to engage the English in guerrilla warfare. Jeanne then led the army in the capture of territory controlled by the English, including the cities of Troyes, Chalons, and Reims. On June 26, 1429, Jeanne realized her goal of seeing Charles VII crowned king in the traditional manner at Rheims Cathedral. The ungrateful and lethargic Charles then denied Jeanne the resources to continue the struggle and, indeed, sought to discredit her.

Despite Charles VII’s lack of support, Jeanne d’Arc was determined to liberate Paris. But English reinforcements arrived in the city in August, and Jeanne’s attack on September 8, 1429, failed, and she was wounded. Still unsupported by King Charles VII, she led a small French force to Compiegne, which the English and Burgundians were besieging as part of the effort of English regent John, Duke of Bedford, to reestablish English control over the central Seine Valley, but on May 23, 1430, Jeanne was captured by the Burgundians, who turned her over to the English. Brought to trial by the English on charges of heresy, Jeanne was convicted and executed at Rouen on May 30, 1431. To his lasting shame, King Charles VII made no effort to save her. The English, however, created in Jeanne a martyr and ultimately a saint.

French resistance to the English grew, although Duke John waged a skillful defense of the English holdings in France until his death on September 14, 1435. In 1435 the English and French opened diplomatic talks. The English refused, however, to relinquish claims to the French throne and insisted on a marriage between the adolescent King Henry VI of England (crowned King Henry II of France in Paris at age nine in 1431) and a daughter of French king Charles VII. The English then broke off negotiations to deal with a French raid.

Meanwhile, Philip, Duke of Burgundy, agreed to join the negotiations. By the time the English returned to the talks, they discovered that Burgundy had in effect switched sides. Under the terms of the Treaty of the Peace of Arras of September 21, 1435, Philip agreed to recognize Charles VII as king of France. In return, Philip was exempted from homage to the French throne, and Charles agreed to punish the murderers of Philip’s father, Duke John of Burgundy. The Treaty of Arras thus brought to an end the long Burgundian- Armagnac strife and allowed Charles VII to consolidate his position as king of France against the claim of Henry VI. With France already allied with Scotland, England was now largely isolated and vastly outnumbered in terms of population. Thereafter its position in France steadily eroded.

In 1436 French forces besieged Paris. With food in short supply, Parisians loyal to Charles VII allowed the besiegers entry to the city on April 13. The English then withdrew to the Bastille, where they were starved into submission and subsequently allowed to withdraw. This ended 16 years of English control of the city. A general amnesty followed.

On April 16, 1444, the English signed at the city of Tours a five-year truce, hoping that the demobilization of large numbers of French soldiers, many of whom would be roaming the countryside, would bring anarchy and strengthen their hand. The inept French king Charles VII, however, followed the advice of his principal ministers to the extent of authorizing the creation of a standing professional army (the first in Europe since Roman times) to enforce the peace. This produced a well-trained force capable of contesting the English on an equal footing. With French resources so much greater than those of England, France’s victory was now largely a matter of time.

With the expiration of the Truce of Tours in 1449, Charles VII had the forces ready to begin a campaign to retake Normandy. The French were led by Jean d’Orléans, Comte de Dunois, and had the benefit of a highly effective siege artillery train established by Jean Bureau, master of artillery, and his brother Gaspard Bureau. Facing the inept English commander Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, the French forced the surrender of Rouen on October 19, 1449. The French then besieged and quickly took Harfleur in December 1449 and Honfleur and Fresnoy in January 1450. They laid siege to Caen in March 1450.

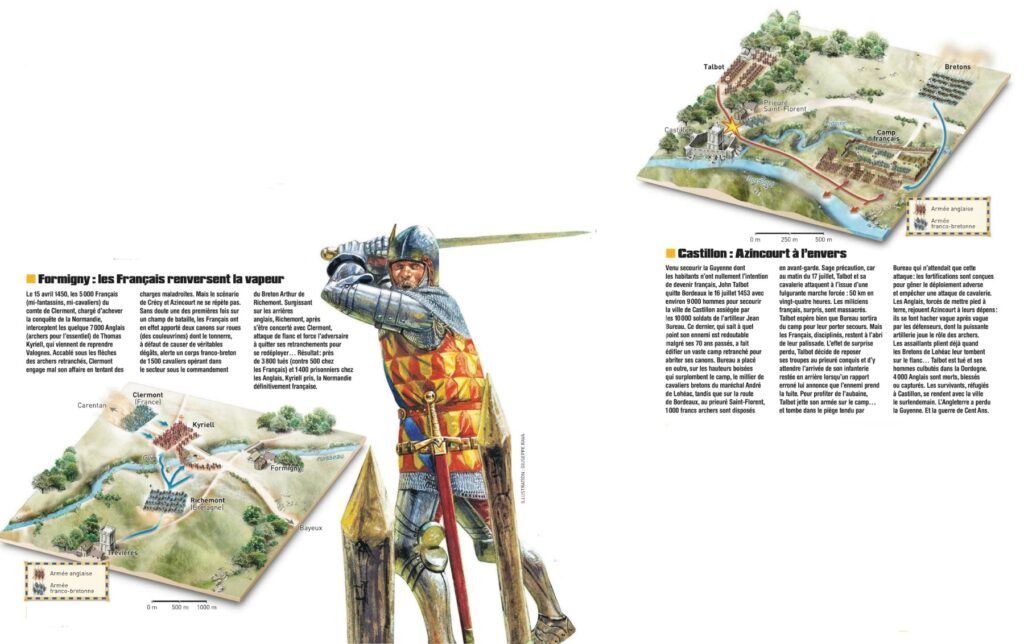

The English assembled a small army of about 3,000 men under Sir Thomas Kyriell. It landed at Cherbourg on March 15, 1450. Instead of going to the aid of Caen, though, Kyriell diverted his force to capture Valognes. Although successful in this, the battle was costly in terms of casualties. At the end of March an additional 2,500 men arrived under Sir Matthew Gough, but Kyriell still had only about 4,000 men as he proceeded southward. Two French armies were just south of the Cotentin (Cherbourg) Peninsula in position to engage the English. The Comte de Clermont commanded 3,000 men at Carentan, 30 miles south of Cherbourg, while the Constable de Richemont had 2,000 more 20 miles farther south at Coutances and now hurried north to join Clermont.

On April 14 Kyriell was camped near the village of Formigny on the road to Bayeux about 10 miles west of that city. Clermont was at Carentan, 15 miles west of Bayeux, while Richemont was moving through Saint-Lo, 19 miles southwest of Bayeux, hoping to link up with Clermont and prevent the English from reaching Bayeux. In midafternoon on April 15, Clermont approached the English camp. Alerted, Kyriell drew up his forces in the traditional English formation that had worked so many times in the past: some 600 men-at-arms in the center and close to 2,900 longbowmen en echelon on the flanks behind planted stakes and narrow trenches. The English formation was backed against a small tributary of the Aure River.

Clermont opened the Battle of Formigny with infantry attacks followed by cavalry. The English easily beat them back. Clermont then brought forward two cannon, which effectively harassed the English archers out of longbow range, leading the longbowmen to charge and capture the guns.

This inconclusive fighting lasted about three hours, sufficient time for the Constable de Richemont to arrive with his largely mounted force. He fell on the English left flank, forcing Kyriell to abandon part of his prepared position. In a series of charges, the French crushed the English for an over- whelming victory. The English sustained some 2,500 killed or seriously wounded, with another 900 taken prisoner, including Kyriell. The French suffered only about 500 casualties. The battle was one of the first in Western Europe in which cannon played a notable role. During the next several months, the French secured the remainder of Normandy. Caen fell on July 6, and Cherbourg surrendered on August 12.

In 1451, the French began the final chapter of the long Hundred Years’ War when Jean d’Orléans led some 6,000 men in an invasion of Guyenne in southwestern France. Benefiting greatly from their siege artillery train under Jean Bureau, the French captured the regional capital of Bordeaux on June 30 and Bayonne on August 20. Nonetheless, many Aquitaine nobles who-thanks to generations of English rule-identified with the English rather than the French continued to resist.

Although the French army in short order conquered Guyenne, resistance continued. Indeed, a number of the nobles and Bordeaux merchants sent a delegation to London that convinced King Henry VI to dispatch an army. It numbered some 3,000 men led by John Talbot, Earl of Shrews- bury. A veteran of much of the fighting in the war, he was now in his 70s. The English landed near the mouth of the Garonne on October 17, 1452, and the leaders of Bordeaux turned over the city to them. Other cities and towns of Guyenne quickly followed suit, effectively undoing the French conquest of 1451.

The French were caught by surprise, having expected the English expeditionary force to land in Normandy. Thus, it was not until the summer of 1453 that Charles VII had put together an invasion force. Three French armies sliced into Guyenne from different directions, and Charles VII followed with a reserve army. English reinforcements under Talbot’s son, Lord de Lisle, arrived at Bordeaux, bringing total English strength up to about 6,000 men. Loyal Gascon forces supplemented this number.

In mid-July, the French eastern army laid siege to Castillon, west of Bordeaux on the Dordogne. Jean de Blois, Comte de Perigord and Vicomte de Limoges, was nominal head of the army, but actual command was held by master of artillery Jean Bureau, assisted by his brother Gaspard Bureau. In operations against Castillon, the French employed some 300 guns, most undoubtedly small. Up to 6,000 men were in the French camp, largely an artillery park beyond artillery range of Castillon and designed by Jean Bureau for defensive purposes. Another 1,000 French men-at-arms were in another camp about a mile to the north. Bureau placed some 1,000 French archers in the Priory of St. Laurent north of Castillon, where a relief force from Bordeaux might most logically be expected.

Talbot departed Bordeaux on the morning of July 16 with mounted troops followed by infantry and artillery. He had at least 6,000 English and Gascons. His men passed through St. Émillon on the night of July 16-17 and in the morning surprised the French archers in the priory, killing a number and scattering the remainder. Talbot allowed his men the opportunity to rest following their 30-mile march but then received a report that the French at Castillon appeared to be withdrawing. Wishing to strike his enemy at the most vulnerable, Talbot ordered an immediate attack without waiting for the arrival of his English-Gascon infantry.

Crossing the Lidoire River that joins the Dordogne from the north, Talbot paralleled the Dordogne to come in on the French artillery camp from the south. The French were prepared, and the English encountered a hail of gunfire from behind the earthen defenses. Talbot ordered his men to dismount and attack the French parapet on foot. Few reached it. With the English-Gascon infantry committed to the battle as they arrived, the French were able to defeat their enemy piecemeal. Breton cavalry then hit the English in the flank to cut off any retreat.

The attackers sustained some 4,000 casualties, including those captured. It was in effect Crécy and Agincourt in reverse, with the decisive element being cannon fire rather than archers. The French sustained perhaps only 100 casualties. The Battle of Castillon was decisive. With no field army left to support them, the remaining towns and cities of Guyenne quickly fell.

Bordeaux surrendered to Charles VII on October 10, 1453, following a three-month siege. Held by the English for three centuries, it was now definitively French. Bordeaux’s capture effectively ended the Hundred Years’ War, although coastal raids continued for the next four years.

Significance

Beginning as a feudal struggle between France and England, the Hundred Years’ War came to assume a nationalist character. The war saw rapid military change, with the creation of a standing army and new weapons, technology, and tactics. The long struggle presaged the demise of the armored knight and the rise of the infantry as the dominant military arm. The fighting, coupled with the Black Death, devastated much of France. During the course of the war the total French population may have declined by as much as half, to 17 million. Normandy was particularly hard hit, losing perhaps three-quarters of its population.

Although the war created considerable wealth for many Englishmen through their ransom of captive French nobility, it also nearly bankrupted the English government and ultimately brought on a series of civil wars in England known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487). And although English monarchs continued to refer to themselves as king or queen of France until 1802, the English were obliged to give up all of their territory in France except for Calais, which itself was relinquished in 1558.

The establishment of professional armies late in the war also marked the end of feudalism. France was transformed from a feudal state to a more centralized state, with increasing power vested in the monarchy and where the people came to think of themselves as Frenchmen rather than, say, Normans or Bretons. The Hundred Years’ War also created a strong enmity between England and France, leading to a rivalry that lasted until the Entente Cordiale of 1904.

Further Reading Barber, Richard. Edward Prince of Wales and Aquitaine. London: Allen Lane, 1978. Bourne, Alfred H. The Crécy War. Reprint ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1976. Clowes, William Laird. The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present, Vol. 1. London: Sampson Low, Martson, 1897. Froissart, Jean. Froissart’s Chronicals. Edited by John Jolliffe. London: Harvill, 1967. Gies, Frances. Jean of Arc: The Legend and the Reality. New York: Harper and Row, 1981. Hewitt, H. J. The Black Prince’s Expedition of 1355-1357. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester Press, 1958. Hibbert, Christopher. Agincourt. New York: Dorset, 1978. Keegan, John. The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo & the Somme. New York: Vintage Books, 1977. Rodgers, William Ledyard. Naval Warfare under Oars, 4th to 16th Centuries: A Study of Strategy, Tactics and Ship Design. 1940; reprint, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1967. Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years’ War: The English in France, 1337-1453. New York: Atheneum, 1978. Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years’ War: Trial by Battle. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988. Warner, Marina. Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism. New York: Knopf, 1981.

Frequently Asked Questions about the 100 years war

Who won the hundred years war?

The French won the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), with the final engagement being the Battle of Castillon in 1453.

What was the hundred years war?

The Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) was a series of conflicts between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France. The conflict was on and off over roughly a 116 year period.

How long was the hundred years war?

The Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) lasted 116 years, 4 months, 3 weeks and 4 days.

When was the hundred years war?

The Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) started on May 24th, 1337 and ended on October 19th, 1453. Lasting 116 years, 4 months, 3 weeks and 4 days.