Toraplane

In 1939 Sir Dennistoun Burney and Nevil Shute worked together on an air-launched gliding torpedo, the “Toraplane”, and a gliding bomb, “Doravane”. Despite much work and many trials the Toraplane could not be launched with repeatable accuracy and it was abandoned in 1942.

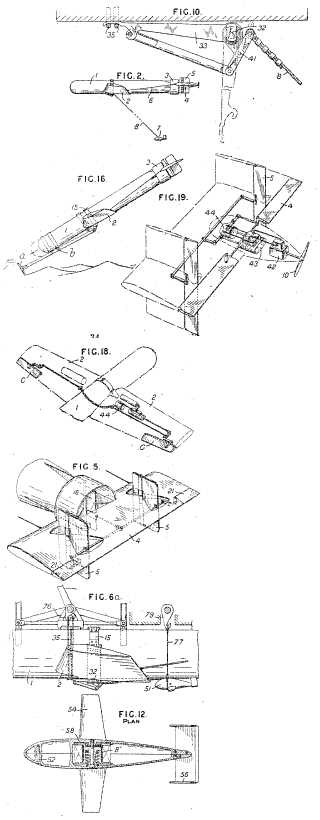

Toraplane was the first of two torpedo remote-attack schemes. The risks faced by torpedo-bombers when approaching a target close enough to drop their weapons successfully were well understood and a means of overcoming these was sought. The inventor, Sir Dennis Burney, believed that a torpedo could be dropped from beyond the range of AA fire by fitting it with detachable wings and tail permitting it to be released some miles from the target (depending on visibility) and then glide down to sea level in stabilised flight. Development of this device, known as Toraplane, or Tora for short, began in August 1939, initially using the Mk XIV torpedo as the payload. The metal or wooden wings of the Mk I version had 3 or 4 degrees dihedral and spanned 11ft 4in. Intended for use by Albacore, Beaufort, Botha and Swordfish aircraft, all of which dropped it on many trials conducted by the Torpedo Development Unit, Tora I was never satisfactory and was replaced by the Mk II.

Tora II was intended for the Albacore, Barracuda and Beaufort only, as Toraplane could not be carried by the Hampden or Wellington adapted for torpedo dropping. This had metal wings spanning 14 or 15ft set at 6 degrees dihedral. Weight with a Mk XII torpedo, the standard load for wartime trials, varied between 1,790 lbs and 1,840 lbs. Recommended launching speeds for Tora II were about 135 mph for the Albacore and some 170 mph for the two monoplanes.

For an attack the optimum release height was 2,500 ft from an aircraft flying at a steady speed and completely level in all planes, after which the Toraplane’s flight-in-air involved a 5,000-yard glide to sea level. A pendulum, suspended just below the wings, struck the water an instant before main impact, releasing the Toraplane from the torpedo. The latter would then run normally. The many trials failed to perfect this theoretical approach, as the slightest anomaly at release or the effect of any adverse wind would be magnified during the long glide. Also, it was difficult to estimate a distant target’s bearing, range and speed, and an alert target had plenty of time to manoeuvre onto an avoiding course.

Toraplane was never used in action and despite the huge cost and effort involved, was cancelled on 15 October 1942.

#

Some info on the Toraplane from a paper by Roger Hayward:

Toraplane was the first of two torpedo remote-attack schemes. The risks faced by torpedo-bombers when approaching a target close enough to drop their weapons successfully were well understood and a means of overcoming these was sought. The inventor, Sir Dennis Burney, believed that a torpedo could be dropped from beyond the range of AA fire by fitting it with detachable wings and tail permitting it to be released some miles from the target (depending on visibility) and then glide down to sea level in stabilised flight. Development of this device, known as Toraplane, or Tora for short, began in August 1939, initially using the Mk XIV torpedo as the payload. The metal or wooden wings of the Mk I version had 3 or 4 degrees dihedral and spanned 11ft 4in (3.454m). Intended for use by Albacore, Beaufort, Botha and Swordfish aircraft, all of which dropped it on many trials conducted by the Torpedo Development Unit, Tora I was never satisfactory and was replaced by the Mk II.

Tora II was intended for the Albacore, Barracuda and Beaufort only, as Toraplane could not be carried by the Hampden or Wellington adapted for torpedo dropping. This had metal wings spanning 14 (4.267m) or 15ft (4.572m) set at 6 degrees dihedral. Weight with a Mk XII torpedo, the standard load for wartime trials, varied between 1,790 lbs (812 kg) and 1,840 lbs (835 kg). Recommended launching speeds for Tora II were about 135 mph (217 kmh) for the Albacore and some 170 mph (274 kmh) for the two monoplanes. For an attack the optimum release height was 2,500 ft (762m) from an aircraft flying at a steady speed and completely level in all planes, after which the Toraplane’s flight-in-air involved a 5,000-yard (4572m) glide to sea level. A pendulum, suspended just below the wings, struck the water an instant before main impact, releasing the Toraplane from the torpedo. The latter would then run normally. The many trials failed to perfect this theoretical approach, as the slightest anomaly at release or the effect of any adverse wind would be magnified during the long glide. Also, it was difficult to estimate a distant target’s bearing, range and speed, and an alert target had plenty of time to manoeuvre onto an avoiding course.

By the end of 1941 doubts about the usefulness of this device became more appearing. Trials against vessels under way showed that the Toraplane ws no more successful than the ordinary torpedo. Toraplane was never used in action and despite the huge cost and effort involved, was cancelled on 15 October 1942.

#

In 1939 Sir Dennistoun Burney and Nevil Shute worked together on an air-launched gliding torpedo, the “Toraplane”, and a gliding bomb, “Doravane”. Despite much work and many trials the Toraplane could not be launched with repeatable accuracy and it was abandoned in 1942.

Shute attended some of the 40+ trials of the Toraplane gliding torpedo off the coast of the Isle of Wight. These trials had the co-operation and support of the Admiralty and had the active support of Winston Churchill who was then the First Lord of the Admiralty. Shute attended several meetings of The Toraplane Development Committee and was referred to as “Mr.Norway – Sir Dennis Burney’s assistant”. Landfall, which was almost certainly begun immediately after this time, mirrors these events.

This paravane deployed below the Toraplane and was used to detach the wings just before entry into the water. (JA)

#

Sir Dennistoun Burney (the inventor in the Great War of the mine-sweeping paravane) got support for many of his ideas. The Toraplane was a set of detachable wings and tail fitted to a torpedo which could then be released at a very great distance from its target, gliding most of the way; two versions were tested, and though both failed the project nevertheless ran for three years. The wings and tail were detached when a small paravane hit the water in advance of the torpedo. The essential problem appeared to be a profound lack of accuracy.

The Beaufort was of immensely strong construction, and at the time of its introduction was claimed to be the fastest medium bomber in the world. Its two Taurus engines gave a top speed of 290 miles per hour and a cruising speed of some 145 knots. The crew of four were well accommodated in the fuselage. The navigator had a fine view from the perspex nose, and could pass readily to and from his take-off position on the right of the pilot. The wireless operator was comfortably seated in the fuselage directly behind the pilot, separated from him by armour plating and by the radio equipment; he, too, could move easily about the aircraft, and when going into action or under attack by fighters he left his seat at the radio and manned two free Vickers machine-guns which were mounted in the waist hatches, one on either side of the fuselage. The power-operated turret sat on the back of the aircraft about half way along the fuselage, and the two gunners could readily swap places to give them a change and to reduce fatigue. Sitting alone in a turret in daylight, scanning the sky hour after hour for other aircraft, was a taut and wearying occupation.

All previous torpedo training had been carried out on the Swordfish and the Wildebeest, whose cruising speed was well under a hundred knots, and the method of attack for these aircraft had been to dive down towards the target from a comparatively safe height, flatten out, and launch the torpedo. But the Beaufort built up speed very rapidly in a dive-far too much speed for the successful launching of a torpedo. It was not possible to lose this speed quickly by flattening out. So the Beaufort attack had to be made at low level, both the approach and the drop. Various attempts were made to remove this tactical limitation, by the fitting of dive-brakes, and by the introduction of a flying torpedo known as a ‘toraplane’, which could be dropped from a height of 1500 feet and which flew into the water at the correct angle. But neither method proved itself in trials, and neither was used operationally. The low-level approach, with the Beaufort exposed to the full weight of defensive fire for a long period and unable to take more than very limited evasive action, had come to stay.

Helmover

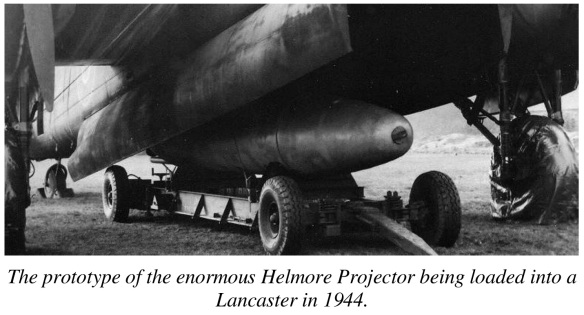

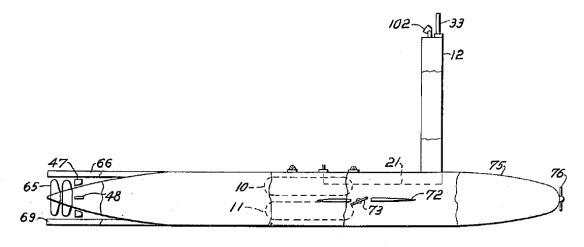

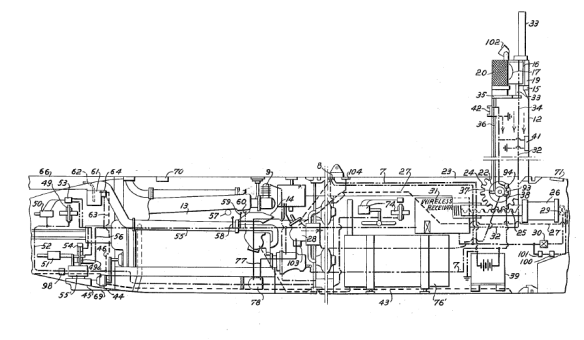

The other torpedo remote-attack scheme was a radio controlled project initiated by the inventive Gp Capt W Helmore. By 1944 it had become an airborne weapon of gigantic proportions called the Helmore Projector, and scale models of the operational device were constructed by Messrs Stone. By about mid-1944 the weapon became Helmover.

This was a giant torpedo with a diameter of 38½ inches and a length of 29 feet. Weighing 11,500 lbs overall, its warhead contained a ton of RDX explosive. Powered by a 700 hp water-cooled Rolls- Royce Meteor engine, based on the Merlin, Helmover had a speed of 40 knots both surface-running and submerged, but its surface range of 50 miles dropped to only three miles submerged. A retractable mast carried an air intake and the receiving aerial for radio control from a Mosquito, which had to fly a pattern of figures of eight to keep the missile’s wake or smoke plume in sight. In the final stage of an attack the mast would be lowered and Helmover would submerge.

Stone’s first prototype featured a tapered nose when used for loading trials, but before the first drop it was modified to typical torpedo shape. This complete, but non-running, prototype was dropped off the Isle of Wight on 21 May 1944 from Lancaster ME570/G of the Torpedo Development Unit. By September control of the project had passed from Messrs Stone to Rolls-Royce at Hucknall. There, production and testing of true prototypes began, with the first running prototype becoming available on 4 February 1945. A successful demonstration to VIPs on 4 April led to a production order for 100 Helmovers, which it was hoped would be used against the Japanese fleet.

Unfortunately, further trials revealed that the visual range of Helmover from the controlling aircraft was rather less than the desired 10 miles. Also, the Mosquito was not ideal for tracking, as Helmover was lost to view for some 50% of the time, owing to the speed and wide turning circle of the aircraft: but there was nothing better. The vulnerability of the controlling Mosquito resulted in the need for a fighter escort, but even then probable operational losses were expected to be unacceptably high, and other means of control were being examined when peace brought the cancellation of the project.

There was a proposed ship-launched version which was much longer to provide more volume for fuel and oxygen cylinders. This measured 49’9″ long and weighed 20,900 lb. Ranges were 150 miles surfaced, 8 miles submerged. I’ve no idea how they would have controlled that (perhaps a spotter plane) but it makes the 24″ Long Lance look like a little toy…

There’s a ten-page chapter on it in ‘Rolls-Royce Armaments’ by David Birch, published by the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. An excellent book, with much information about lots of obscure projects.

Johnny Walker

“Bomb, H.E., Aircraft, J.W., 400lb. Mk.I” or short “J.W. Bomb”

#

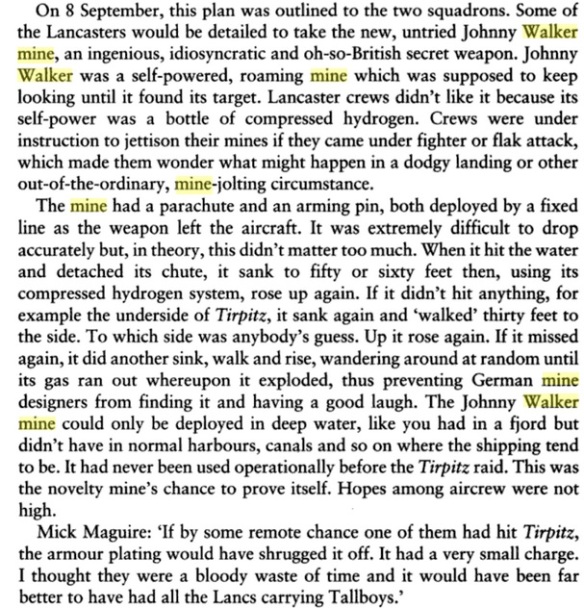

The German battleship Tirpitz lying in Alten Fjord in Norway, tied down British naval units which would have been better deployed elsewhere. Even from the most northerly of British airfields Alten Fjord was outside Lancaster range. A deal was struck with the Russians, who made Yagodnik, near Arkhangelsk, available as a refuelling stop. For this and subsequent anti-Tirpitz operations, No.617 was joined by No.9 Squadron, which, although fitted with the Mk XIV vector bombsight, was also something of an elite outfit. Of the 36 Lancasters detailed, 24 carried Tallboys; the others were loaded with 12 Johnny Walker Diving Mines each, an original but ineffective weapon.

#

Twenty aircraft are loaded with the 12,000 pound (5 443 kilogram) Tallboy bomb and six (or seven, the records are not clear) carried several ‘Johnny Walker’ mines, of 400-500 pound (181-227 kilogram) weight developed for attacking capital ships moored in shallow water.

#

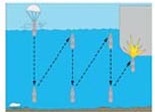

The weapon to be used was 617’s Tallboy s, the only bomb which could penetrate the ship’s armour. The other weapon to be used was the JW bomb which had a weight of 4,000 lbs and 90 lbs of Torpex. It was designed on the principle of the oscillating mine for attacks on enemy shipping. The trim of the bomb was so adjusted that it moved vertically but sideway s in water as well. If it hit the bottom of a ship on its upward path it would fire. On release from the aircraft the parachute opened by a static cord, and the safety pin was withdrawn from the fuse on impact with the water. The parachute released and fell away and in so doing pulled a flexible wire starting the gas to the fuse and cocked the self-destruction device. These would be dropped in a lake on the north side of the fjord which would be unaffected by the smoke screen around the ship.

#

Although the battleship was still afloat she was barely seaworthy and in no condition to fight, the Tallboys had been a success whereas the JW mines had failed to detonate within the proximity of Tirpitz and drifted around the fjord before exploding well away from their intended target.

Bombers, First and Last By: Gordon Thorburn