A total of 89 heavy artillery guns and Katyusha rocket launchers were trained on the Reichstag for a thunderous barrage before the infantry stormed it, turning the structure into a ruin.

When the Reichstag was finally taken on 30 April 1945, Soviet soldiers swarmed through its elegant hallways to scrawl graffiti recording their presence, and their feelings about the Germans.

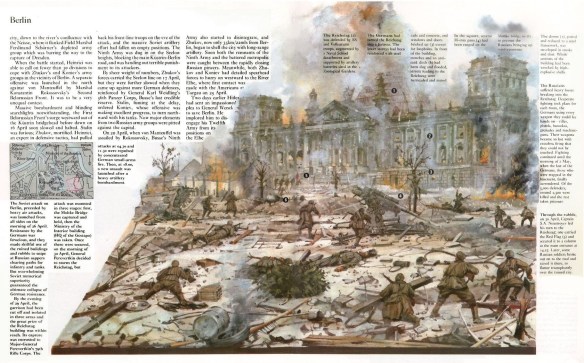

By the evening of the 28th April 1945, Marshal Zhukov’s lead forces were preparing the final assault on the Reichstag. Chuikov’s Eighth Guards advanced from the south, Berzarin’s Fifth Shock Army with 11th Tank Corps from the east, and Kuznetsov’s Third Shock Army the unit designated to make the actual seizure – from the north-west. The spearhead unit from Third Shock was General S. N. Perevertkin’s 79th Rifle Corps. They had two major obstacles to overcome before they reached the Reichstag building. First, the Moltke Bridge would have to be seized and a crossing of the Spree forced. To this task was assigned 171st Rifle Division. Then, after the corner building on the opposite Kronprinzenufer had been cleared, the 171st would have to join the 150th Division in neutralising the huge complex of the Ministry of the Interior – ‘Himmler’s House’ – which was expected to mount a terrific resistance. Late on the 28th, the Germans attempted to blow the Moltke Bridge, but the explosion left the centre section hanging precariously in place. The Soviet soldiers tried to force a crossing but were driven back by murderous fire from German pillboxes. Shortly after midnight, however, two Soviet battalions succeeded in blasting their way through the barricades and across the bridge, where they proceeded to clear the surrounding buildings to allow a crossing in force.

At 0700 hours the next morning, Soviet artillery began a 10-minute pounding of ‘Himmler’s House’. Mortars were also hauled up to the second floor of a next-door building and fired point-blank through the windows. The infantry began the assault, but it was another five hours before they managed to storm into the complex’s central courtyard. The fighting was intense and vicious. Close-range combat was pushed from room to room and up and down the stairways. Finally, at 0430 hours on 30 April, the Ministry of the Interior building was secured, and the Red Army troops began taking up their positions for the storming of the Reichstag.

While this battle raged, just a few hundred yards away, the last Fuhrer-conference was getting underway in the bunker. General Weidling reported on the situation, sparing nothing in his description of the city’s, and the Third Reich’s, plight. There was virtually no ammunition left, all of the dumps being now located in Soviet-occupied sectors of the city; there were few tanks available and no means for repairing those damaged; there were almost no Panzerfausts left; there would be no airdrops; an appalling number of the ‘troops’ left defending the city were red-eyed youngsters in ill-fitting Volkssturm uniforms, or feeble and frightened older men or those who had been earlier deemed unfit for military service. It was inevitable, Weidling told Hitler, that the fighting in Berlin would end soon, probably within a day, with a Soviet victory. Those present reported later that Hitler gave no reaction, appearing resigned to his fate and the fate he had inflicted on the country. Still, when Weidling requested permission for small groups to attempt break-outs, Hitler categorically refused. Instead he glared dully at the situation maps, on which the locations of the various units had been determined by listening in to enemy radio broadcasts. Finally, around 0100 hours, Keitel reported to the Fuhrer that Wenck was pinned down, unable to come to the Chancellery’s aid, and that the Ninth was completely bottled up outside the city. It was over. Hitler made his decision to kill himself within the next few hours.

Around noon on the 30th, the regiments of the l50th and l7lst Rifle Divisions were in their start positions for the attack on the Reichstag. In a solemn though brief ceremony, several specially prepared Red Victory Banners were distributed to the units of Third Shock Army which, it was thought, stood the best chance of being the first to hoist it over the Reichstag. In l50th Division, one banner was presented to 756th Rifle Regiment’s. First Battalion, commanded by Captain Neustroyev; another went to Captain Davydov’s First Battalion of the 674th Regiment; a third to the 380th’s First Battalion, led by Senior Lieutenant Samsonov. Banners were also given to two special assault squads from 79th Rifle Corps, both of them manned by elite volunteer Communist Party and Komsomol (Young Communist League) members.

At 1300 hours, a thundering barrage from 152mm and 203mm howitzers, tank guns, SPGs, and Katyusha rocket launchers – in all, 89 guns – was loosed against the Reichstag. A number of infantrymen joined in with captured Panzerfausts. Smoke and debris almost completely obscured the bright, sunny day. Captain Neustroyev’s battalion was the first to move. Crouching next to the captain, Sergeant Ishchanov requested and was granted permission to be the first to break into the building with his section. Slipping out of a window on the first floor of the Interior Ministry building, Ishchanov’s men began crawling across the open, broken ground towards the Reichstag, and rapidly secured entrances at several doorways and holes in the outer wall. Captain Neustroyev took the rest of the forward company, with their Red Banner, and raced across the space, bounding up the central staircase and through the doors and breaches in the wall. The company cleared the first floor easily, but quickly discovered that the massive building’s upper floors and extensive underground labyrinth were occupied by a substantial garrison of German soldiers. One floor at a time, they began attempting to reduce the German force. The task uppermost in everyone’s mind was to make their way to the top and raise the banner; the soldiers who succeeded in this symbolic act, it had been promised, would be made Heroes of the Soviet Union. Fighting their way up the staircase to the second floor with grenades, Sergeants Yegorov and Kantariya managed to hang their battalion’s banner from a second-floor window, but their efforts to take the third floor were repeatedly thrown back. It was 1425 hours.

Immediately after the beginning of the attack on the Reichstag, German tanks counter-attacked against the Soviet troops dug in around the Interior Ministry building. The 380th Regiment, which had been attempting to storm the north-western side of the Reichstag, came under withering fire and was forced to back off and call for help from an anti-tank battalion. Meanwhile, on the second floor, Captain Neustroyev radioed a request for a combat group to support his men and ordered them to clean out the German machine-guns still on the second floor. Sergeants Yegorov and Kantariya were entrusted with the banner once again, and the battalion readied for the battle to take the third floor.

Towards 1800 hours, another strong assault was launched up into the third floor of the Reichstag. This time the Red Army infantrymen succeeded in blasting their way through the German machine-gun positions. Three hundred Soviet soldiers now occupied the German parliament building but a much larger number of heavily armed German soldiers remained in the basement levels. However, the Soviets enjoyed the better position and after a number of tense hours, in the early morning hours of 1 May – the Soviet workers’ holiday, and the target date for their conquest of Berlin – they finally cleared the remaining Germans from the building. Even before all German opposition had been wiped out, at 2250 hours, two Red Army infantrymen climbed out onto the Reichstag’s decimated roof and hoisted the Red Victory Banner. Berlin was under the control of the armies of the Soviet Union.