An almighty explosion

As the sun slipped up over the lush green Javanese countryside, the battle for Meester Cornelis got under way. Gillespie and his men forced their way across the Slokan and overwhelmed Redoubt Number Four in a welter of close combat.

Eventually the missing columns appeared from the forest and joined an attack on the next redoubt. But on the brink of storming it, the British were subjected to an almighty explosion. A pair of French captains, in an early instance of a suicide bombing, had immolated themselves in the powder store – with dramatic consequences, as Captain Thorn recorded: ‘The ground was strewn with the mangled bodies and scattered limbs of friends and foes, blended together in a horrible state of fraternity.’

Despite this shocking incident, Gillespie’s men pushed on, deeper into the Cornelis fortifications. More redoubts fell. Guns were seized. An attempted Dutch cavalry charge from the bowels of the fort faltered fast under fire.

Very soon the assault had triggered a rout, and the defenders were fleeing south through the forest, heading for the Dutch hill-station of Buitenzorg, with the British in furious pursuit. By the time they had gone ten miles, the British had taken 5,000 prisoners.

Once more, it was shaky loyalties that had caused Janssens’ defence to collapse. One appalled Napoleonic officer recorded the scene as he was dragged back towards British lines: ‘With a feeling of shame and indignation I saw more than one [Dutch] officer amongst them trample on his French cockade, to which he had sworn allegiance, uttering scandalous imprecations and swearing and assuring the English: “I am no Frenchman, but a Dutchman.” ‘

Lord Minto, who had been safely ensconced offshore during the worst of the fighting, visited the battlefield the following day, and was horrified: ‘The number of dead and the shocking variety of deaths had better not be imagined.’ But in truth the outgunned British had achieved victory at minimal cost. Just 62 British soldiers and 17 Indian sepoys had died in the attack on Meester Cornelis.

Janssens and a small body of Napoleonic officers had escaped and fled east to Semarang, where they attempted to organize a second line of defence. Auchmuty set out in pursuit.

Eventually, on 18 September, at the little upland garrison of Salatiga, Janssens – who was almost alone by the end – ceded control of the Dutch East Indies to the British. He stressed, however, that ‘as long as I had any [men] left me, I would never have submitted’.

The British interregnum

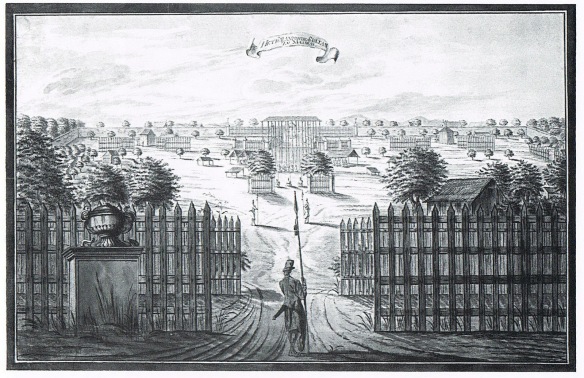

The five-year interregnum that followed the fall of Batavia was, in truth, a rogue operation. Lord Minto’s instructions from the Supreme Government had ordered him to organize only ‘the expulsion of the Dutch power, the destruction of their fortifications, the distribution of their arms and stores to the natives, and the evacuation of the Island by our own troops’.

But with his Romantic notions of ‘the land of promise’, as well as supposed concern for the fate of Dutch civilians, he unilaterally decided to retain the territory. He and Auchmuty returned to India in October 1811, leaving the inexperienced Raffles as lieutenant-governor, with Gillespie as his military counterpart.

Today Raffles is best remembered for the subsequent founding of Singapore, and is usually portrayed as a liberal reformer, a gentleman scholar, and an acceptable counterpoint to the more aggressive aspects of British colonial history. His actions in Java, however, reveal him to have been a personification of the shift from the earlier 18th-century style of ‘company colonialism’ towards the grand imperialism of the coming Victorian Age.

During the previous century, in both British India and the Dutch East Indies, there had been room for compromise. The agents of the Dutch and British East India Companies had often tried to further European commercial interests without seeking to overturn the sovereignty of native courts. Some of their number had engaged with Asian cultures in a manner that would be anathema in a later epoch, participating in local society, legitimately marrying Asian women, and even converting to Islam.

Raffles’ arrival in Java marked an abrupt end to such acculturation, and his five-year reign on the island was a microcosm of the wider transition from the era of the ‘White Mughals’ to that of the ‘Queen Empress’.

Raffles rampant

The European enemy had been roundly trounced, but there were other powers in Java – the great native courts of the hinterland, Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Raffles decided that they constituted an unconscionable challenge to his authority.

By early 1812 he had decided that he needed to organise a crushing military defeat of one or other of these courts as ‘decisive proof to the Native Inhabitants of Java of the strength and determination of the British Government’.

In June that year he made his move, ordering an attack on Yogyakarta on the flimsy pretext of an uncovered correspondence discussing an uprising against the Europeans which had, in fact, been instigated by the Surakarta court.

Yogyakarta was the more significant of the two realms and, wrote Raffles, ‘the Sultan [of Yogyakarta] decidedly looks upon us as a less powerful people than the [Napoleonic] Government which proceeded us, and it becomes absolutely necessary for the tranquillity of the Country that he should be taught to think otherwise.’

If the conquest of Batavia had been a remarkable success for an outnumbered British force, the subsequent sacking of Yogyakarta was, on paper at least, a feat of almost superhuman status. On 20 June 1812, most of Britain’s military manpower was tied up in Sumatra, where Raffles had ordered a punitive expedition against the Palembang Sultanate. With just 1,200 men at his disposal, therefore, he now instructed Gillespie to launch an attack on the walled city of Yogyakarta, a place defended by some 10,000Javanese troops.

The storming of Yogyakarta

In truth, however, the turn of events was such an earth-shattering shock to the Javanese that their defence collapsed almost at once. Yogyakarta had inherited the mantle of past javanese kingdoms such as Mataram and Majapahit. It was a place of high protocol and of a complex Muslim-Javanese courtly culture that drew on an older Hindu and Buddhist heritage.

During the previous two centuries, conflicts between the Dutch and the Javanese courts had been typified by formalized posturing and brinkmanship, and had then usually been resolved through face-saving diplomacy. The Sultan of Yogyakarta, Hamengkubuwono II, had never believed that the British would really attack, and once the sepoys began to surge over the walls his court descended into panic. As one Javanese prince, Arya Panular, noted, ‘In battle [the British] were irresistible… they were as though protected by the very angels and they struck terror into men’s hearts.’

The assault began at dawn, and by 9am it was all over. Though they had been outnumbered by almost ten to one, the British lost just 23 men. The Sultan was arrested and exiled, and the victors fell to enthusiastic looting of the city. Gillespie took away personal booty valued at GBP 15,000 (half a million, in modern terms) while Raffles and the British resident at Yogyakarta, John Crawfurd, stole the entire contents of the court archives. The following afternoon the Crown Prince was placed on the throne as a British puppet, and during the coronation the courtiers were forced to kiss Raffles’ knees in the ultimate Javanese act of subjugation.

Writing to Lord Minto to inform him of the victory, Raffles declared that it had ‘afforded so decisive a proof to the Native Inhabitants of java of the strength and determination of the British Government, that they now for the first time know their relative situation and importance… The European power is now for the first time paramount in Java.’

The return of the Dutch

After the fall of Yogyakarta, peace returned to Java. But the new British administration rapidly descended into disorder. A vicious clash of personalities emerged between Raffles and Gillespie.

They had been ill-suited to being left in charge of a complex colony – one man a bruising aristocratic war-hero, the other an ambitious if insecure middle-class civilian; and neither with any real experience of government. They were, according to one visitor, ‘at constant variance and daggers drawn’, and Gillespie eventually lodged formal accusations of corruption against his civilian counterpart. Meanwhile, a series of budgetary blunders and ill-planned and overreaching reforms pushed the colony to the brink of an economic meltdown.

Raffles and Minto had dreamed of making Java a permanent British possession, controlling traffic between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. But in the circumstances the higher authorities were all too eager to hand it back to the Dutch once the wars were over in Europe, and Holland had regained its sovereignty.

When they returned in 1816, the Dutch found administrative and financial chaos; but there was also another, more useful inheritance. The great native courts had finally been hobbled. There would be no return to old modes of compromise: the European power was indeed finally paramount in Java, and the scene had been set for the coming colonial century, both in the Dutch East Indies, and in the wider Asian continent beyond.