The invasion of Java in 1811 was a successful British amphibious operation against the Dutch East Indian island of Java that took place between August and September 1811 during the Napoleonic Wars. Originally established as a colony of the Dutch Republic, Java remained in Dutch hands throughout the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, during which time the French invaded the Republic and established the Batavian Republic in 1795, and the Kingdom of Holland in 1806. The Kingdom of Holland was annexed to the First French Empire in 1810, and Java became a titular French colony, though it continued to be administered and defended primarily by Dutch personnel.

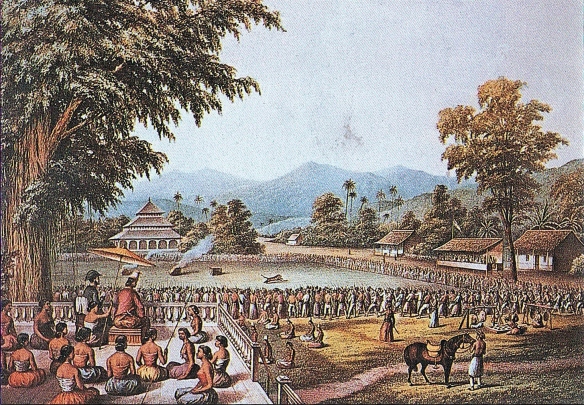

After the fall of French colonies in the West Indies in 1809 and 1810, and a successful campaign against French possessions in Mauritius in 1810 and 1811, attention turned to the Dutch East Indies. A expedition was dispatched from India in April 1811, while a small squadron of frigates was ordered to patrol off the island, raiding shipping and launching amphibious assaults against targets of opportunity. Troops were landed on 4 August, and by 8 August the undefended city of Batavia capitulated. The defenders withdrew to a previously prepared fortified position, Fort Cornelis, which the British laid siege to, capturing it early in the morning of 26 August. The remaining defenders, a mixture of Dutch and French regulars and native militiamen, withdrew, pursued by the British. A series of amphibious and land assaults captured most of the remaining strongholds, and the city of Salatiga surrendered on 16 September, followed by the official capitulation of the island to the British on 18 September. The island remained in British hands for the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars, and was restored to the Dutch in the Treaty of Paris in 1814.

The invasion

The column of soldiers moved silently through the forest, picking their way along muddy trails between dense stands of betel-nut trees. Already the thick tropical heat was rising, and their red jackets were sodden with sweat.

It was an hour before dawn on 26 August 1811, and the men – British redcoats and Indian sepoys – were heading for the formidable fastness of Meester Cornelis, the great redoubt of Batavia, grand old capital of the Dutch East Indies. Inside the fortifications was a massed force of Dutch, French, and Javanese troops. In the words of one British participant, the ‘day that was to fix the destiny of Java’ had arrived.

The prize

British Invasion Of Java- Todaís Indonesia – the former Dutch East Indies – lies largely beyond the horizon of the English-speaking imagination. But in the second decade of the 19th century it was the scene of a dramatic episode of British colonial history.

The five-year British interregnum in Java, which began with the battle for Batavia in August 1811, was a period of furious controversy that would have a lasting impact on Indonesian history. It also marked a significant chapter in the life of the man best known today for the founding of Singapore: Thomas Stamford Raffles.

Holland, in the form of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India Company, had been involved in Indonesia for more than two centuries. The company had established Java, the 600-mile long lodestone of the Indonesian archipelago, as the hub of its nascent empire, naming Batavia on the north coast of the island as capital, and setting up a network of outposts across the region.

Britain, meanwhile, was increasingly entrenched in the Indian Subcontinent, and had little interest in South-East Asia. But war in Europe changed all that.

In the winter of 1794, Napoleon invaded Holland and installed a puppet republican regime. For the British authorities, all Dutch overseas territories became de facto enemy territory – though pressing concerns closer to home meant that it was not until 1810 that the British East India Companís governor-general in Calcutta, Gilbert Elliot, Lord Minto, received instructions to ‘proceed to the conquest of Java at the earliest possible opportunití. The following year a fleet of 81 troop-ships departed India on course for Batavia.

Minto and Raffles

Lord Minto

The advance on Java had the air of a Sunday outing. Lord Minto -a dandyish 60-year-old civilian -had taken a personal interest in the project, and together with his collaborator, the 30-year-old Thomas Stamford Raffles, a former clerk in the administration of Penang, he had developed a wildly Romantic view of java as ‘the land of promise’.

Regimental wives and civilian hangers-on had tagged along for the adventure, and as the fleet lumbered across the Java Sea, they were entertained by the antics of strapping young sailors dressed as ‘young, accomplished, and generally sentimental ladies of quality.

On 4 August the fleet dropped anchor in the murky waters of Batavia Bay, and the 12,000-strong invasion force was landed at the undefended fishing village of Cilincing, eight miles east of Batavia. The forces were evenly split between British regiments and units from the Bengal Presidency Army.

Batavia’s climate was notoriously unhealthy, and it was hoped the Indians would fare better than Englishmen; in the event, they began to succumb to fever before the first shot was fired.

The commander-in-chief was the New York-born veteran Lieutenant-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty, and the commander of the forces in the field was the feisty 45-year-old Irishman Colonel Rollo Gillespie.

The Dutch settlement of Batavia formed a linear development, running inland from the mouth of the Ciliwung River, eight miles west of the British landing spot. First came the walled city of Old Batavia, built in the early 17th century; three miles inland was the modern garrison of Weltevreeden; and a further three miles towards the mountains stood the fortress of Meester Cornelis.

Auchmuty and Gillespie had expected first to engage enemy forces in Old Batavia, but when they reached the city -the eight-mile advance took several days, so intersected with canals and fishponds was the country – they found that the Dutch had already abandoned it.

Dutch ploys

Jan Willem Janssens

The Dutch-Napoleonic army in Batavia amounted to a mixed force of some 18,000 men. At their head was the governor-general Jan Willem Janssens, a committed Dutch republican who wrote his letters in florid French. He had already presided over one notable defeat at the hands of the British at the Battle of Blaauwberg in South Africa in 1806, and it was said that Napoleon had despatched him to Java with an ominous warning: ‘Know, sir, that a French General is not offered a second chance.’

Janssens had abandoned Old Batavia as a deliberate ploy, hoping that the British would rapidly succumb to the malaria endemic there, and could then be pinned down in the pestilential alleyways. As an imaginative additional measure, he had ordered that copious quantities of alcohol should be left in the abandoned houses, in the hope that the British would drink themselves into a stupor.

Gillespie issued strict orders for sobriety. A tentative Dutch assault on the southern gates of the walled town was seen off. And the best efforts of a requisitioned French servant to fell the top brass with a batch of poisoned coffee had only limited results. Then, before dawn on 10 August, a 1,500-strong British force moved south along the road to Weltevreeden. But once more, the British found that Janssens had already pulled back his forces.

An elusive foe

Some of the British began to wonder if they would ever get the chance to fight in Java. But as they pressed on, now heading northwards through a dense stand of pepper trees, they finally came under sustained fire for the first time. The Dutch had set up field guns on either side of the road, and had felled trees to block the way.

Gillespie, who was still vomiting from time to time as a result of the poisoned coffee, ordered two parties to loop out left and right to attack the enemy positions from the flank, while a third party scrambled forward under covering fire to haul the trees out of the way.

It was all over in minutes, and the Dutch forces were soon fleeing through the forest towards Meester Cornelis, despite the best efforts of their officers to rally them.

At one point, Janssens’ chief of staff, General Alberti, who had become separated from his own men, ran into a small party of the green-coated British 89th. Mistaking them for his own troops, Alberti began upbraiding them angrily for retreating without orders – at which point a private of the 89th shot him in the chest (though he ultimately survived).

The problem that Janssens faced was not one of numbers; it was a question of loyalty and quality. Many of the Dutchmen were aging veterans of the former VOC army -the VOC itself having been disbanded shortly after the French invasion of Holland – and they had little, if any, commitment to the Napoleonic cause. The Javanese conscripts had still less interest in fighting.

A number of French soldiers had been shipped out in recent years, but they were reportedly the dregs of the Republican army, deemed of little use on European fronts. Now they bolted for the final fastness of Meester Cornelis, where Gillespie and Auchmuty set up a siege.

Cannonade

Marshal Daendels

Meester Cornelis was a formidable fortress. Built by Janssens’ predecessor, Marshal Daendels, it comprised five miles of fortifications studded with 280 pieces of heavy cannon, and was flanked to the west by the meandering Ciliwung River, and to the east by a deep canal called the Slokan. The surrounding countryside, meanwhile, was ‘intersected with ravines, enclosures, and betel plantations, resembling hop-grounds, many parts of which could only be passed in single file’

Over the coming days the British kept up a heavy cannonade against the northern walls of Cornelis. Gillespie and Auchmuty were sensitive to the dangers of a stalemate in the morbid Javanese climate. They had arrived with the advantage of energy and health, but by mid-August heat and fever were taking their toll, and they knew they must act. And so, in the early hours of the morning of 26 August, the final stealthy assault began.

Small parties were sent out to attack the fortress from all angles, while the bulk of the British forces under Gillespie headed off through the forest to launch a surprise assault across the Slokan from the east, the point they had judged the weakest. The plan was to launch simultaneous operations at first light.

In the event Gillespie almost met with disaster. As the first section of the advance huddled in the trees just a few hundred yards from the first Dutch pickets, they realised to their horror that the thousands-strong column that should have been snaking up behind them was nowhere to be seen: they had got lost in the betel plantations.

It was, in the words of Captain William Thorn, a close confidant of Gillespie, ‘One of those pauses of distressful anxiety, which can be better conceived than described.’

Unable to communicate with the other parties, Gillespie decided on a typically brazen course of action: he attacked anyway, sneaking unspotted past the first Dutch sentries, and then launching an unsupported rush on the first redoubts.