Tyre, in what is now Lebanon, was the holdout. It had a unique place as the largest and most important Phoenician port in the eastern Mediterranean, and as an important Persian naval base. Tyre had been a prominent city for centuries by the time that Alexander arrived. The Phoenician merchants from Tyre had been among the first people to send their trading ships throughout the Mediterranean. The city grew rich and powerful and was coveted by its neighbors. King Nebuchadnezzar II, known as “the Great,” who built the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, had unsuccessfully besieged the city for 13 years in the sixth century BC. Eventually, the Tyrians threw in their lot with the Persians.

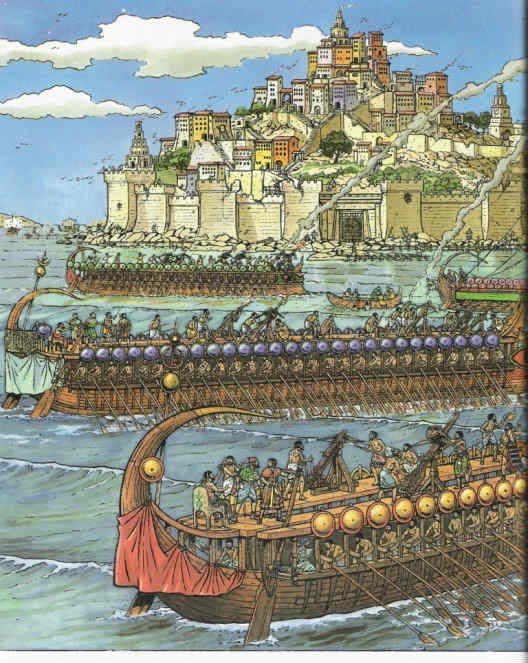

To secure their metropolis, the Tyrians built a new city on an island a half mile offshore from the old city on the mainland. This new Tyre was now an impregnable fortress surrounded by two miles of stone walls that were reportedly as high as 150 feet. The island had two ship harbors, the northern one named for Sidon, the southern one named for Egypt. Through these harbors, Tyre could be supplied from the sea, regardless of who controlled the adjacent mainland.

Alexander had hoped to avoid the necessity of a siege entirely. He was optimistic when his army was met on the coast road by ambassadors from Tyre, who told him, according to Arrian, that the city “had decided to do whatever he might command.”

Alexander said he would like to enter their city and offer a sacrifice to Heracles—known to the Tyrians as Melqart—at the temple that had been erected to him in the southern part of their island citystate. He explained that he was descended from Heracles, as were all of the kings of Macedonia. Their response was not what he expected. The Tyrians, then ruled by King Azemilcus, told him he was welcome at another temple of Heracles located on the mainland, but he could not enter the island.

With this, the die was cast. Tyre must be taken. Thus began an epic siege that took place over the spring and summer of 332.

In a speech possibly transcribed by Aristobulus or Callisthenes, and passed down by Arrian, Alexander told his officers of his strategic view of the eastern Mediterranean, explaining why Tyre was so important:

“I see that an expedition to Egypt will not be safe for us, so long as the Persians retain the sovereignty of the sea; nor is it a safe course, both for other reasons, and especially looking at the state of matters in Greece, for us to pursue Darius, leaving in our rear the city of Tyre itself in doubtful allegiance. . . . I am apprehensive lest while we advance with our forces toward Babylon and in pursuit of Darius, the Persians should again conquer the maritime districts, and transfer the war into Greece with a larger army.”

The conventional wisdom held that Tyre could be assaulted only from the sea, and its huge, solid walls would protect it from that. Besieging Tyre presented a dilemma, given that the Tyrian fleet and the allied Persian fleet under Autophradates had naval superiority in the eastern Mediterranean, while Alexander had deliberately undercut his own navy.

According to folklore, readily retold by Arrian as fact, the solution came to Alexander in a dream. He dreamed that Heracles took him by the right hand and led him up into the city, walking on dry land. Though the dream needed little in the way of interpretation, it was declared to be a good sign by Aristander, the seer who had once told Philip II that his son within the womb of Olympias would be as bold as a lion. Alexander had relied on his prognostications more than ever after he correctly predicted the victory at Granicus.

If Tyre was separated from dry land by a half mile of water, he would just take the dry land to the city. Alexander decided to solve the problem at hand by turning Tyre from an island into the tip of a peninsula by building a causeway to it from the mainland.

The portion of the channel closest to the shore was a gently sloping tidal plain. There was an abundance of rock and other construction material nearby, so getting started on this project would be relatively easy. Closer to the island fortress city, however, the channel was 18 feet deep, so it would be more challenging. A difficult task under any circumstances, building a causeway here beneath hostile walls was a serious problem for work crews with Tyrian archers raining projectiles down upon them.

However, morale inside the walls was shaky as well. The Tyrians too, had a dream. They dreamed that Apollo told them he was, as Plutarch paraphrases it, “going away to Alexander, since he was displeased at what was going on in the city.”

The project began with wooden pilings being driven into the mud with a roadway constructed on top. The work proceeded rapidly at first, but as the Macedonians got into the channel, the crews came under fire from Tyrian warships. To stave off this harassment, Alexander had two tall siege towers constructed at the end of the causeway from which his troops could return fire against the ships. Their elevated position meant that the men in the towers could see farther, and their projectiles had greater range, than they would from near sea level.

The Tyrians struck back using a transport barge as an incendiary device. They piled it high with wood scraps and other flammable material, including pitch and brimstone. To its masts they fitted long double yardarms, attaching caldrons containing additional flammable material. They towed the barge near the causeway towers using triremes, setting it on fire as it neared the towers at the end of the causeway. The yardarms were long enough to cantilever over the causeway and strike the towers, which were soon engulfed in flames.

Attempts by Alexander’s personnel to fight the fires were met by archers aboard the triremes. The Tyrians also landed troops on the causeway who burned catapults and other equipment before withdrawing. After a stroke of engineering brilliance in his causeway idea, Alexander had been halted rather ignominiously.

However, it was merely round one. Alexander promptly ordered the causeway to be widened and new towers to be built. Meanwhile, he decided to acquire additional warships of his own, having realized that defeating Tyre would require sea power after all.