Hitting Qaddafi

On the evening of 14 April the attention of the Qaddafi regime was still focused on the carriers of Task Force 60, not the F-111Fs approaching from the west, but that was about to change. As the F-111Fs and their support aircraft traveled the long way in getting to Libya, they were detected by early-warning radars in several countries. While the radar operators in France, Spain, and Portugal kept silent, their counterparts in Italy alerted Malta, a country sympathetic to Qaddafi. About thirty minutes before the strike the Maltese warned Tripoli of a formation of U.S. Air Force planes flying over the central Mediterranean. Nevertheless, this new information apparently had little impact on the level of readiness of Libyan air defenses. “The steady sequence of building pressure from 3 to 14 April did not produce increased Libyan vigilance but fatigue,” observed military historian Daniel Bolger, the author of Americans at War, 1975-1986: An Era of Violent Peace. “Tripoli evidently ignored the flurry of late afternoon and early evening conjectures as the American forces assembled.”

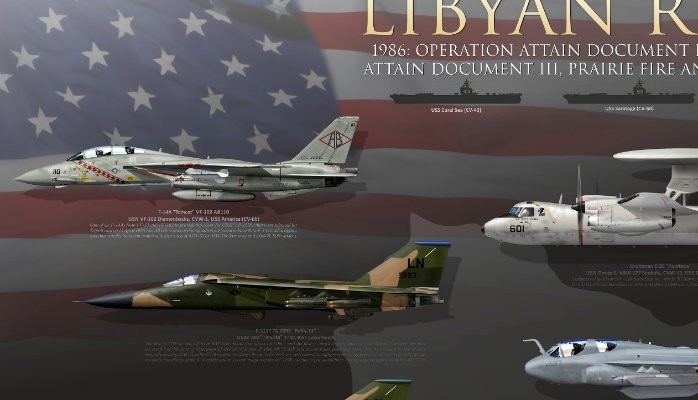

At 0150 Tripoli time, while the F-111Fs and A-6Es hugged the deck and bore down on their targets in Tripoli and Benghazi, the jammers and SAM busters went to work against what Secretary of the Navy Lehman described as “one of the most sophisticated and thickest” air defense systems in the world.30 EF-111As and EA-6Bs began smothering Libyan air search radars with powerful electronic noise, and a couple of minutes later the pilots of the A-7Es and F/A-18s, who knew the locations and operating frequencies of most of the Libyan SAM radar sets, began unleashing a devastating barrage of HARM and Shrike missiles. The missiles knocked out radars serving SA-2 Guideline, SA-3 Goa, SA-6 Gainful, SA-8 Gecko, and French-built Crotale SAM batteries, and opened paths for the attacking aircraft. Sixteen HARMs and eight Shrikes were fired at Tripoli air defenses; twenty HARMs and four Shrikes were launched at radar sites in Benghazi. The exploding warheads devastated active radar sites, shredding delicate antennas and raining hot, jagged fragments on support equipment and control facilities.

The operators of the SA-5 battery at Surt did not activate their radar until the strike aircraft had completed their attack runs and were outbound over the Mediterranean. Most likely the operators elected to stay out of the action, having learned their lesson the hard way on the night of 24–25 March.

Meanwhile, the mission commander of an America-based E-2C described the exhilaration he felt the moment he switched his AN / APS-125 radar from standby to radiate: “The excitement really started . . . when we actually started picking up the people on our systems, when we started seeing these guys coming in from the western Mediterranean. . . . One of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen is that large number of Air Force aircraft come in. Their timing was incredible—right on the money, within seconds of when they were supposed to be there.”

Comdr. Jay Johnson, commander of America-based CVW-1, observed firsthand the state of Libyan readiness from the cockpit of his F-14 at his MiG CAP station twenty-five miles from Tripoli: “I came in at a low altitude and popped up on the clock and said, ‘Holy Cow, this is a city that’s asleep!’ . . . They didn’t have a clue.” Streetlights were shining in both Tripoli and Benghazi, and in the capital floodlights bathed the largest buildings and the minarets of the central mosque. Stumpf discovered that the Libyans had not extinguished the runway lights of the Benina Airfield, “which provided a visual beacon for the bombing runs.” The shining street and runway lights could have led one to conclude that the Libyans did not think an attack was imminent, but the element of surprise did not last long.

As the bombers approached their targets the Libyans threw up a dense volume of SA-2s, SA-3s, SA-6s, SA-8s, Crotales, and radar-guided ZSU-23/4 AAA. To the low flying F-111Fs and A-6Es the most deadly threats in Qaddafi’s arsenal were the Crotales and AAA, both of which were far more capable against low-altitude targets than any of the Soviet-built SAMs. Luckily, most of the SAMs were not guided, thanks to the effectiveness of the U.S. jammers and ARM-firing aircraft. Errant missiles and wild AAAs streaked through the black skies over Tripoli and Benghazi, having little effect except to paint a terrifyingly surreal nocturne for the Air Force and Navy bomber crews as they bore down on their targets. “Once we proceeded inbound to the target, there were a couple of SAMs launched,” an A-6E pilot heading for Benina observed. “We were lit up, so they were looking for us, and they were shooting at us, but as far as I could tell. . . [the missiles] weren’t guiding.”

As seven F-111Fs pressed their attack on Bab al-Aziziyah at an altitude of a couple hundred feet and 600 miles per hour, adrenaline was pumping and tension was palpable in each cockpit. Several concerns occupied the thoughts of the pilot of the lead plane, Remit-31. He worried about the performance of the terrain-following radar, so he constantly monitored its performance to make sure it did not fly his plane into the ground. He worried that he was not going fast enough and would arrive late over the target, so he kept his hand on the throttle to adjust air speed. He worried that the wind over the target might have shifted, thus obscuring aim points for the bombers following him. He worried that his WSO would not be able to locate the radar offset point—an operation crucial to the success of the mission. And he worried about the Navy SAM-busters taking up their positions on time. “I had no idea whether the Navy had launched,” he said. “The first time I ever saw or heard another airplane was forty seconds prior to my bomb release, when I looked up and saw a Navy A-7 firing a Shrike at a radar emitter. And boy that gave me a warm, fuzzy, good feeling inside.”

A few moments later the instruments on the pilot’s console in Remit-31 indicated that the plane was 71,000 feet from Qaddafi’s headquarters-residence building. As the plane roared over Tripoli harbor the pilot noticed several boats firing off flares. At just that moment a beeping sound went off in his headset, which indicated that he was being tracked by Libyan fire control radar. To evade the radar he descended to an even lower altitude which, although a good tactic, made it more difficult for his WSO to acquire his radar offset point—a set of piers in the harbor—on his radarscope. The WSO had loaded into the F-111F’s computer the precise bearing and range of the aim point from the piers. If the WSO could lock his radar on to the offset point the computer would steer the plane automatically to the target. Therefore, for their attack to have any chance of success, it was essential that he find the piers. The plane’s current speed and altitude made the task extremely difficult. He urged his pilot to pull up, but an instant later he located the offset aim point. “Yeah, we’re looking good,” he told his partner. He was confident that they were heading for Aziziyah.

While Remit-31 was closing in on Aziziyah a number of network TV correspondents in Tripoli spoke over open telephone lines with their anchors back in the United States. It was exactly 0200 in the Libyan capital and 1900 on the East Coast. NBC correspondent Steve Delaney reported hearing the roar of a jet outside the window of his hotel room. Seconds later, millions of viewers of NBC Nightly News heard explosions and the crackle of gunfire. “Tom, Tripoli is under attack!” Delaney told Tom Brokaw, the anchorman in New York.

At the command center in the Pentagon Admiral Crowe and Secretary of Defense Weinberger waited for reports from CINCEUR headquarters in Germany and from the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. In the meantime they listened to the CNN correspondent in Tripoli describe the city as calm and quiet but very tense. Suddenly the reporter shouted, “I’m hearing bombs and gunfire! . . . I can see rockets! I think there’s an attack going on!” Crowe and Weinberger broke out in wide smiles. The strike was right on time.

As Remit-31 hurtled toward Aziziyah, the pilot asked his WSO for the range to the target. At first the WSO could not respond, because he had not yet located the target building using the FLIR camera mounted beneath the aircraft. “Range!” demanded the pilot. An instant later the WSO replied: “Target direct.” On his FLIR screen he could see Qaddafi’s headquarters-residence building with the air-conditioning unit centered on the roof. As the range to the building ticked down to twenty-three thousand feet, the WSO warned his pilot, “Ready.” When the range hit twenty-three thousand feet the WSO shouted, “Pull!” The pilot immediately initiated a Pave Tack Toss, pulling the nose of his plane up sharply and sending the four-ton payload straight to the heart of Qaddafi’s terror network. After the bombs were released the pilot wrenched his plane into a 4G left-hand turn. As he was the first plane over Aziziyah he had the luxury of making his attack before the Libyan defenders were fully alerted. Nevertheless, as he performed the evasive maneuver he watched as a stream of ZSU-23 tracers tried in vain to catch the bomber’s tail. To evade the AAA the pilot turned even tighter.

While the pilot performed the toss and escape maneuvers the WSO kept his head buried in his FLIR screen, struggling to keep the laser beam fixed on the target. He was able to hold the beam on the target until a second before impact. At that instant the plane’s sharp turn caused the laser to slip from the target. “You pulled too hard!” the WSO shouted. For the last second of their flight the bombs were in an unguided free fall. That single second made all the difference between a direct hit and an extremely near miss. At the stroke of 0200, four 2,000-pound bombs impacted a few yards from the building that served as Qaddafi’s headquarters and living quarters.

After the bombs hit the pilot immediately sought the safety of a lower altitude. “I’m going down,” he told his WSO, pushing the plane down to three hundred feet. “We hit ’em big time!” the WSO reported, his FLIR screen filling with billowing smoke and dust. Remit-31 was back over the Mediterranean in less than a minute. He reported “feet wet”—meaning he was flying safely away from the Libyan coast—to the Navy E-2C and the Air Force command KC-10A, then followed his statement with the code word “tranquil tiger,” which indicated a successful attack.

Realizing he was a few seconds behind schedule, the pilot of Remit-32 frequently used his afterburner to make up the time. He had almost reached the point twenty-three thousand feet from the aim point and was about to perform the Pave Tack Toss but was forced to abort when, at the last instant, his WSO realized he was targeting the wrong aim point—a problem caused by an equipment failure that had gone undetected. The pilot retained the four 2,000-pound bombs, took manual control of the aircraft, and performed a highspeed, low-level escape from downtown Tripoli. Remit-32 barely eluded the determined efforts of Libyan gunners, whose notice was attracted by his excessive use of afterburner. After reaching the Mediterranean he reported “feet wet” and “frosty freezer,” which meant that his attack had been aborted. He later jettisoned his bomb load at sea.

More than a minute after Remit-31 dropped its bombs, Remit-33 carried out its attack on Aziziyah. After the four 2,000-pound bombs were released, the WSO could not hold the target on his FLIR scope. The surface winds had shifted from their predicted direction and the smoke and debris thrown up by the bombs from Remit-31 obscured the target. Consequently, the bombs fell to earth unguided. Nevertheless, they still impacted a couple of hundred feet from the target: a large administration building within the Bab al-Aziziyah compound. Remit-33 also escaped just ahead of a heavy SAM and AAA barrage.

Although the 2,000-pound bombs dropped by Remit-31 and Remit-33 did not achieve direct hits, they did cause considerable damage to Qaddafi’s compound. The Paveways had collapsed walls and caved in the roofs of several buildings within Aziziyah. New York Times reporter Edward Schumacher toured the facility two days after the raid and counted eight large bomb craters extending in a line from the front of Qaddafi’s house to an administration building located atop the colonel’s reinforced bunker. He noticed that the line of bombs passed within fifty yards of Qaddafi’s ceremonial tent, knocking out a number of supports within and collapsing part of its cover. Schumacher reported that two bombs had hit within thirty yards of Qaddafi’s residence, devastating the building. The 2,000-pound bombs shattered windows, blew out doors, collapsed ceilings, and demolished the contents of several rooms. Washington Post correspondent Christopher Dickey also toured the compound. He guessed that one of the 2,000-pound bombs had exploded within sixteen yards of the front entrance of the residence, producing a crater four feet deep and fifteen feet in diameter.

Elton-43, the fourth plane in line to attack Aziziyah, developed a bleed air casualty to one of its engines when it was just short of the target. The problem disrupted the crew’s concentration at the critical moment of their attack run and forced them to abort.

Immediately after releasing their bombs, the pilot and the WSO in Karma-51—the fifth plane over Aziziyah—realized that the attack had not gone well. The WSO had been unable to update his plane’s inertial navigation system after the strike force took the shortcut to get back on schedule. After dropping away from the tanker he fixed his plane’s position using a small island in the central Mediterranean as a reference point, but unbeknownst to him the location of the island, according to the plane’s computer software, was off by several hundred feet. This inaccuracy, along with the pressures of high-speed, low-altitude flight, made it extremely difficult for the WSO to locate his offset aim point. Consequently, as the plane raced toward the Libyan coast he had inadvertently selected the wrong aim point. The computer placed the target in another location-one-and-a-half miles away—and it dutifully guided the plane to that position. As a result, Karma-51 dropped its bombs late and long. The pilot noticed that the bombs took a few more seconds to release than they should have, and the WSO searched his FLIR screen for the aim point in the Aziziyah compound but could not find it. In fact, nothing on the screen resembled Bab al-Aziziyah. Since he was unable to find the target, the WSO could not use the laser designator. Therefore, he had no choice but let the bombs fall ballistically. The four 2,000-pound LGBs smashed into a civilian neighborhood near the compound. The bombs demolished a number of houses and apartment buildings and damaged—ironically—the French Embassy. Unfortunately, several innocent Libyans were killed and injured in the regrettable attack. The Austrian, Finnish, Iranian, and Swiss Embassies also reported sustaining minor damage. During the attack the crew of Karma-51 had been in great danger. After their return to Lakenheath an analysis of their mission tape revealed that a Libyan SAM had locked on to their plane.

Several F-111Fs used their afterburners to get through the volleys of SAMs and AAA as quickly as possible. The airmen who had flown combat missions in Vietnam acknowledged that the Libyan AAA was not as dense as they had experienced over Hanoi, but the Tripoli SAMs were more formidable. Fortunately, due to the effectiveness of the jammers and ARM-firing aircraft, most Libyan air defense crews were forced to launch their weapons optically. Although the afterburners provided a tremendous burst of energy, the long sheets of flame spewing from the exhaust pipes provided a brilliant target for Libyan gunners. As the raid progressed the density of SAMs and AAA steadily increased, but none of the weapons hit the first five planes over Aziziyah. Each crew breathed a huge sigh of relief as their plane reached the coast. The sixth plane in the stream over Aziziyah, Karma-52, was not so fortunate. It was hit by either a SAM or AAA prior to reaching the target. Making a beeline for the coast, the plane caught fire and went out of control. The pilot, Capt. Fernando Ribas-Dominicci, and the WSO, Capt. Paul Lorence, ejected seconds before their F-111F exploded and the huge fireball slammed into the sea. Unfortunately, their ejection capsule hit the water before the chutes could fully deploy. The fliers were knocked unconscious and subsequently drowned. Karma-52 would not be declared missing until all surviving F-111Fs had marshaled with their tankers for the first post-strike refueling. Libya soon recovered the body of Captain Ribas-Dominicci but did not return it to the United States until 1989. An autopsy determined the cause of death to be drowning, not massive physical trauma. Although there is not enough information to determine exactly what caused the loss of Karma-52, the autopsy finding and the eyewitness accounts of several aviators who saw the explosion and the descent of the fireball to the sea support the conclusion that Karma-52 was shot down by a SAM or AAA. The fact that Ribas-Dominicci’s body did not contain evidence of fractures or internal injuries challenges the theory that Ribas-Dominicci simply flew his plane into the water due to pilot error.

Karma-53, the last plane in line to attack Aziziyah and the one slated to drop a second set of 2,000-pound bombs on Qaddafi’s headquarters-residence building, experienced a last-second combat systems malfunction and was forced to abort in the vicinity of the target.

As Karma-53 passed over Aziziyah the Jewell attack group commenced its strike on the terrorist training facility at Murat Sidi Bilal. The Libyan defenses were lighter there, because the target was located a few miles west of downtown, but the winds at the target, like those at Aziziyah, were significantly different from what had been forecasted. The first two planes to attack Murat Sidi Bilal—Jewell-61 and Jewell-62—delivered their 2,000-pound bombs using the Pave Tack Toss, churning up a tremendous amount of smoke, dust, and debris. Meanwhile, the third plane—Jewell-63—closed in on its target: the building that contained the swimming pool used to train commando frogmen. At a point exactly twenty-three thousand feet from the aim point, the pilot executed a Pave Tack Toss and released his four 2,000-pound bombs. As the bombs arced toward the laser energy reflecting from the building, the WSO coaxed his bombs on to the target: “This one’s for you, Colonel!” Then, an instant later he yelled out in disgust: “Ah, clouds, clouds, clouds!” The dust and smoke from the other bombs had interrupted the laser guidance system and had caused the bombs to fall ballistically. The bombs slammed into the base mess hall, missing the building containing the swimming pool by about a dozen yards. Post-mission damage analysis determined that none of the bombers of the Jewell group scored a direct hit. They did, however, severely damage the mess hall, a classroom building, and an administration-support building and destroyed several small training vessels.

After crossing the beach the six planes in the Puffy and Lujac attack groups flew a long overland route to the Tripoli Military Airfield, a trip that required full use of their terrain-following radars. As the TFRs guided the F-111Fs over the irregular Libyan terrain, the crews constantly monitored the performance of their “Auto-TF” systems. Each pilot kept his hand behind the stick and was ready to raise the nose of the aircraft in an instant, if it looked as though the TFR was about to fly the plane into the desert floor or at an unexpected outcropping. During the transit to the target the strike force was reduced to five aircraft when Puffy-12 developed a problem with its TFR and had to abort.

Flying with TFR over unfamiliar territory was very stressful, but the crews received one important break. As they approached the airfield they realized that they had caught the Libyans completely off guard and would not have to contend with a determined and effective defense. The crews were tempted to catch more than a fleeting glance at the huge fireworks display that was taking place in Tripoli to the north—streaking SAMs, AAA tracers, and exploding 2,000-pound bombs—but they had plenty of work to do studying their own consoles. The pilots kept an eye on the TFR, and the WSOs searched their FLIR screens for the parking ramp with the Il-76 transports.

At 0206 the airmen of Puffy-11 commenced their attack on the airfield. As the plane roared in at less than five hundred feet, the pilot observed the terminal lights ablaze and asked the WSO if he had the parking ramp on his scope. The WSO, his face pressed into the rubber hood covering his scope, responded affirmatively and aimed his laser beam on the middle plane of five transports parked on the flight line. Although the laser-designator system would not guide the 500-pound bombs, it provided crucial data to the pilot. It recommended the correct heading to steer and informed him when to drop his ordnance. Just a few seconds before bomb release the pilot came to the right to center his plane on the target. When the WSO saw the middle Il-76 filling up his FLIR scope, he exclaimed: “Oh baby!” “I’m on the pickle button,” the pilot stated an instant later, as he depressed the bomb-release button. “Here come the bombs.” A string of a dozen 500-pound bombs—each slowed by the ballute drag device—quickly fell behind Puffy-11 and immediately hit the transports parked on the tarmac.

The bombing run performed by Puffy-11 was immortalized by a few feet of videotape shot by the camera mounted in the belly of the F-111F. The exceptionally clear video, which was shown repeatedly on news broadcasts all over the world, displayed hard maneuvering (as the crew struggled to line up on the target), a line of bombs stretching downward toward one of the parked Il-76s, an explosion, and a huge cloud of dust and debris. After delivering his ordnance the pilot of Puffy-11 increased the throttle, turned west to avoid the SAMs and AAA coming out of Tripoli, then streaked north toward the safety of the Mediterranean and the orbiting tankers.

The Snakeyes dropped by Pufíy-11 scored several hits and touched off a number of fires and explosions. Two transports were destroyed and three others suffered considerable damage. As it turned out, Pufíy-11 performed the only completely successful attack on the Tripoli airfield. Minor equipment malfunctions and mistakes had hindered the performance of the other four crews, all of which had failed to score a direct hit on the transports. Instead they caused minimal damage to a number of helicopters parked near the transports and to an operations building.

On the other side of the Gulf of Sidra six Coral Sea-based VA-55 Warhorses bore down on the Benina Airfield. “A-6 crews . . . saw the incoming HARMs’ orange cones of destruction, smothering SAM sites in their paths,” Stumpf recalled. “SAMs that were launched created a sensational effect in the night sky but none guided effectively.” At exactly 0200 local time the Warhorses—one armed with Snakeye high-drag bombs, and five carrying CBU-59 APAMs—devastated the Benina Airfield. The Snakeyes cratered the runway and torched the alert MiG-23s, while the APAM submunitions blanketed the parking apron and battered several aircraft. “The last of the six A-6s across the airfield noted several airplanes on the ramp below burning furiously,” Stumpf said, and “as the Intruders raced for the ocean and safety, they could see the giant bomb explosions of the America’s A-6s on target near the city.”

The attack on Benina demolished three, possibly four, MiG-23 Floggers; two Mi-8 Hip helicopters; one F-27 Friendship propeller-driven transport; and one small fixed-wing aircraft. Damaged planes included one Mi-8, two Boeing 727 transports, one propeller-driven transport, two fixed-wing aircraft, and an undetermined number of MiG-23s, which were probably moved out of sight before the United States could perform a post-strike battle damage assessment (BDA). The Benina hangars received moderate damage, while four other buildings and several vehicles and pieces of ground equipment were destroyed. After the raid the airmen of VA-55 proudly called themselves “the East Coast’s largest distributor of MiG parts.”

An F/A-18 pilot flying support off Benghazi was profoundly relieved when he detected the lights of the city. “If the lights were out, we were in trouble,” he recalled. “It was all lit up like Norfolk or Jacksonville or any other major city.” At the exact moment the Warhorses hit Benina, six VA-34 Blue Blasters off the America struck the Benghazi Military and Jamahiriyya Guard Barracks. They had great difficulty identifying the barracks on radar, since the target was located in a crowded downtown area. Encountering a barrage of SAMs, each Blaster released a “stick” of sixteen 500-pound Snakeye high-drag bombs, which hit the barracks and an adjacent warehouse that served as a MiG-23 assembly facility. Four aircraft shipping crates were destroyed while a fifth was damaged. Unfortunately, two bombs fell a few hundred yards wide of the target and struck a civilian neighborhood, damaging two houses.

From an unparalleled vantage point off the coast the last U.S. aircraft to leave the target area—a pair of F/A-18s assigned to support SAR operations—saw the Benghazi “skyline ablaze with secondary fires from the downtown areas, backdropped by a softer glow from fires burning at the airfield which was several miles inland.” In Tripoli and Benghazi the Libyans kept up a vigorous fusillade in a desperate attempt to knock down what they thought were more attacking aircraft. Several nights would pass before the sporadic firings at phantom bombers would cease, a clear indication of the frayed state of Libyan nerves.