Departing for Tripoli

Colonel Westbrook launched and recovered planes at RAF Lakenheath for Exercise Salty Nation until 1500 U.K. time on Monday, 14 April. After that time all planes taking off from the British base would be bound for Tripoli.

The F-111F mission crews started gathering at 48 TFW in the early afternoon, and those slated to bring up the rear in the nine-plane raid on Bab al-Aziziyah immediately checked to see if the plan had changed. None of them displayed any emotion when they realized that the plan had not been revised. The airmen then assembled in the crew room of the 494th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) for the final briefing on the critical details of the mission: weather, latest intelligence on Libyan defenses, radio communications, refueling procedures, altitudes, speeds, turn points, radar offset points, aim points, escape and evasion plans, and hundreds of other vital pieces of information.

After the formal briefing Westbrook took the floor and addressed his pilots and WSOs. He reminded them that of the twenty-four F-111Fs that would take off from Lakenheath only the eighteen best planes would proceed to Libya. If a plane developed an equipment problem it would return to base, even if it was being flown by one of the squadron commanders or the hottest pilot in the wing. Westbrook reiterated that the ROE were extremely clear and would not be relaxed. The risks to both U.S. aircrews and Libyan civilians had to be kept to a minimum, and therefore a bomber’s electronic systems had to be in full operating order or it would not deliver its ordnance.

Westbrook concluded his presentation by telling his men that another person present wanted to speak to them. He was referring to the chief of staff of the Air Force, Gen. Charles Gabriel. Both events—Exercise Salty Nation and Gabriel’s visit to Lakenheath—had been scheduled well before 48 TFW began its Libya contingency planning. Gabriel had spent the day with Westbrook touring the base, observing the exercise, and gathering first-hand information on Operational El Dorado Canyon. The chief of staff strode from the back of the room to the front, catching many of the men by surprise. He told the F-111F crews that they were not being ordered to do anything they had not been trained to do. “If everybody followed the plan and no one tried to be a hero, the mission would succeed,” he said. “We don’t need any heroes. . . . They’re a liability.”

After the briefing the pilots and the WSOs attended to some very basic needs. They ate a high-protein lunch and packed a substantial “in-flight meal” of sandwiches, fruit, cookies, juice, and a bottle of water and then visited the latrine before climbing into their aircraft. During the long mission, if a flier had to relieve himself he could urinate into a plastic “piddle pack,” which contained absorbent material and could be tightly sealed.

At about 1600 Westbrook and General Forgan, the mission commander who had arrived from Ramstein earlier in the day, drove to Mildenhall where they boarded the KC-10A tanker that would serve as their airborne command post. Aboard the plane technicians were busy checking out the radio equipment that would enable the two officers to stay in contact with the other planes on the mission and with the command centers at Lakenheath, Ramstein, Stuttgart, and in the carrier America. Admirals Kelso and Mauz would operate from the tactical flag command center in the America.

The launch plan for Operation El Dorado Canyon was very complex. Its objective was to put nearly sixty bombers, electronic warfare planes, and tankers into the air from four different bases and do so without tipping off everyone in Great Britain that a large-scale military operation was underway. After the tankers began taking off the F-111Fs and EF-111As would commence launching in a “comm out,” or complete radio silence status. They would join their designated tankers, which would carry out all necessary communications with air controllers on the ground. The Aardvarks and Ravens would fly in close formation with their tankers, and keep their IFF—identification friend or foe—transponders turned off. The Air Force hoped that the strike force would appear to unsuspecting radar operators along the route simply as an unarmed flight of Air Force tankers.

The giant tankers were the first aircraft to depart for Libya. A fleet of twenty-nine KC-10A Extenders and KC-135R Stratotankers began taking off from their bases at RAF Mildenhall and RAF Fairford at 1713 U.K. time (1213 Washington time). The tankers attracted some attention, but with Exercise Salty Nation in progress the British press did not link the departing tankers with the crisis involving the United States and Libya.

At 1735, exactly four minutes after the command KC-10A took off from RAF Mildenhall, the first wave of eight F-111Fs began launching from their base at RAF Lakenheath. The Puffy element was the first to get airborne, since its target, the Tripoli Military Airfield, was the farthest away. Other F-111Fs followed at twenty-second intervals. If everything worked according to plan, in exactly six-and-a-half hours the crew of the lead Puffy aircraft would streak over the tarmac of the Tripoli airfield and drop twelve 500-pound bombs on a row of 1l-76 Candid transport planes. At 1805 the second wave of sixteen F-111Fs started taking off and, at 1831, the first of five EF-111As launched from RAF Upper Heyford. One of the Ravens was a mission spare.

The Aardvarks, Ravens, and tankers passed north of London, rendezvoused over southern England, and formed into their flight cells. The task force then proceeded southwestward toward the Atlantic. For ninety minutes the twenty-four F-111F crews checked and rechecked their aircraft systems and reported the results to their squadron commanders to ensure that the eighteen best planes continued the mission to Tripoli. The other six planes with their bitterly disappointed crews would return to Lakenheath. The departure of the unneeded aircraft would reduce the number of F-111Fs and EF-111As per tanker from four to three—one on each of the tanker’s wings and one under the tanker’s belly.

Near Land’s End the six F-111Fs (Remit-34, Elton-42, Karma-54, Jewell-64, Puffy-14, and Lujac-21), and one EF-111A (Harpo-75) were ordered to return to their bases. The strike force had seven fewer planes but it was nevertheless a sizeable armada, consisting of eighteen bombers, four electronic warfare planes, and twenty-nine tankers. Fliers called a force this size a “gorilla package.” Following the departure of the spare planes the force turned south across the Bay of Biscay. Flying over three hundred knots at an altitude of twenty-six thousand feet, the planes commenced their first in-flight refueling operation.

The dangerous operation was choreographed in advance to eliminate the need for radio communications. As the lead plane in each cell approached the KC-10A’s fueling boom, the other aircraft waited their turn in close formation. At night in radio silence the boom operator, who was lying face down inside the tanker, coached the pilot of the lead plane into position by flashing small signal lights located on the underbelly of the tanker. Once the plane was in position the boom operator guided the fuel probe into the receptacle located behind the cockpit of the fighter. After topping off his fuel tanks the pilot disengaged and slipped to the side, making way for the next customer. In the words of one 48 TFW pilot, in-flight refueling conducted at night with no radio communications was simple. It’s “just like day refueling,” he said, “except you can’t see a fucking thing!” Subsequent refuelings en route to Libya would take place off the coasts of Portugal, Algeria, and Tunisia.

During the long flight to Tripoli each pilot and WSO continuously evaluated his plane’s combat systems and electronics suite. They performed a comprehensive “fence check,” which automatically inspected the inertial navigation system, the terrain-following radar, the attack radar, the self-defense electronic warfare equipment, the Pave Tack FLIR and laser designator, and the switches on the weapons release panel. The crewmen held their breath each time they performed one of the checks. If a problem was detected they would have to abort the mission, considering the stringent rules of engagement. “The hope in every cockpit was that no last-second, hair-on-fire major malfunction would occur,” noted Colonel Venkus. If a problem cropped up it could mean a fourteen-hour, butt-numbing ride for nothing.

The arduous flight put extraordinary demands on the skill and endurance of every cockpit crew. “That’s a long way to fly formation,” the pilot of Remit-31 said. “My arm got tired. My neck got tired. . . . From time to time I would turn on the autopilot just to give myself a rest, but it couldn’t hold formation for very long.”

Earlier in the day, at approximately 1030 local time, the America and the Coral Sea battle groups had commenced high-speed transits from the Tyrrhenian Sea to their scheduled operating areas north of the Tripoli FIR. The Coral Sea and her escorts sprinted through the Straits of Messina, while the America battle group swept around the west coast of Sicily and passed south of Malta. Battle Force Zulu was operating under EMCON Alpha, the complete shutdown of all radios and radars. Mauz hoped that the combination of speed and strict radio silence combined with the onset of darkness would foil the Soviet surveillance vessels that were prowling the central Mediterranean in search of the American fleet. Both battle groups successfully eluded an intelligence-gathering trawler, a Sovremennyy-class destroyer, and a modified Kashin-class DDG that were operating near Sicily and a pair of Soviet IL-38 May patrol aircraft that were flying out of their temporary base in Libya.

While the carriers steamed to their launch areas—the America to the west and the Coral Sea to the east, in a line approximately 180 miles off the coast of Libya—flight deck crews spotted, fueled, and armed the “go birds,” and maintenance crews and electronics technicians performed preflight checks on each aircraft. For the attack planes “go” criteria meant a fully operational bombing and navigation system, mode IV IFF system, chaff dispenser, and radar homing and warning (RHAW) system. The chaff and RHAW systems were used for defense against enemy SAMs. Ordnancemen stenciled bombs with personal messages on behalf of friends or loved ones back home or slogans such as “To Muammar: For all you do, this bomb’s for you” or “I’d fly 10,000 miles to smoke a camel.” Meanwhile, the nuclear attack submarines Dallas (SSN 700) and Dace (SSN 607) established an invisible barrier to block Libya’s fleet of six Soviet-built Foxtrot-class diesel-electric submarines from reaching the battle force.

Consulting Congress, Notifying the Soviets, and Coping with the Media

At 1600 Washington time, President Reagan and his senior national security advisers met with House and Senate leaders to brief them on Operation El Dorado Canyon. “At the conclusion of this meeting, I could call off the operation,” Reagan emphasized. “I am not presenting you with a fait accompli. We will decide in this meeting whether to proceed.” After Reagan and his advisers spoke and after each congressional leader had an opportunity to ask questions and express his concerns about the operation, the president asked if any of the senators or representatives believed that the operation should be canceled. None did. Reagan thanked them for their support and cautioned them about the sensitivity of the information contained in the briefing. After the meeting the lawmakers avoided making comments to reporters that might jeopardize the operational security of the mission.

The Reagan administration waited until the mission was well underway to notify the Soviet government. The Soviet chargé d’affaires in Washington was called to the State Department where Secretary of State Shultz apprised him of the evidence of Libyan involvement in the West Berlin terrorist bombing, informed him of the operation, and assured him that the impending raid was in no way directed against his country.

Inevitably, several journalists examined the circumstantial evidence—Task Force 60 was at sea, Ambassador Walters had completed a tour of allied capitals, and Reagan had just conducted a high-level meeting with congressional leaders—and concluded that an attack was imminent. The flood of news reports coming out of Washington had a very unsettling effect on the aviators of Task Force 60. Commander Stumpf described their reactions thus: “These broadcasts listed target areas and proposed target times, which coincided almost exactly with the actual missions. Many believed chances for success without significant losses had been seriously jeopardized, since a major tactical feature of the strikes was the element of surprise. There was talk of postponing everything until whoever was compromising this vital information could be throttled. Aircrews whose missions would involve flying within enemy SAM envelopes were particularly alarmed by this breach of security.” Fortunately, the press was discussing U.S. military options and probable Libyan targets in very general terms. Crowe was confident that the element of surprise had been preserved. He remarked that “while there was a great deal of talk in the newspapers about the raid and so forth, we went to some effort, and I think we were successful in concealing the time of the raids and the actual targets.” Also reassuring was the fact that the press was focusing its attention on Kelso’s Sixth Fleet, not on the gorilla package plodding southward over the Atlantic.

Closing in on Libya

Shortly after midnight Tripoli time, on 15 April (1700 Washington time on 14 April), the carriers went to flight quarters. The America and the Coral Sea began catapulting their planes into the dark, moonless night at 0045 and 0050, respectively. The America launched six A-6Es and eight SAM-suppression A-7Es. A seventh A-6E developed a problem with its TRAM system and aborted on the flight deck. The Coral Sea launched eight Intruders and a half-dozen anti-SAM F/A-18s, but two A-6Es aborted due to malfunctions with their RHAW and TRAM systems. The carriers also launched other crucial support aircraft: four EA-6Bs and two EA-3Bs for the suppression of the Libyan air defense network; F-14s and F/A-18s for protection of the Tripoli and Benghazi strike groups, defense of the battle force, and support of SAR operations; E-2Cs—a pair for each target sector—for strike coordination, long-range surveillance, CAP control, and SAR coordination; KA-6D and KA-7 tankers for in-flight refueling; and SH-3 helicopters for “lifeguard” duty during launch and recovery cycles and potential SAR missions. In all more than seventy aircraft were launched from the two carriers. Although America-based aircraft flew primarily in support of the Air Force attack on Tripoli, three EA-6Bs and two A-7Es from CVW-1 supported the Navy strike on targets in the Benghazi area.

Flight deck personnel, air controllers, and aircrews carried out the launch in radio silence and with radars in standby or “non-radiate” status. Both launch cycles were completed by 0124. All aircraft planned to operate “zip-lip” until they reached the radar horizon of the Libyan air defense network.

Meanwhile, as the Air Force planes arrived over the western Mediterranean, the pilot of Remit-31 realized that the strike force had fallen more than ten minutes behind schedule and, during a routine radio check, called out the word “time” to draw attention to the fact that the mission was running late. The situation had to be corrected immediately or the entire operation would be placed in extreme jeopardy. In a strike mission employing two separate forces timing is critical, because all surprise vanishes as soon as the first piece of ordnance explodes. If the Navy attacked the Benghazi targets on time but the Air Force planes were late, the Libyan defenders would be fully alerted by the time the F-111Fs arrived over Tripoli. Furthermore, if the bombers were late getting to Tripoli the effects of the Navy SAM suppression efforts would be nullified.

The Tripoli strike force could have fallen behind schedule for a number of possible reasons. It took the EF-111As more time than planned to join the formation. The KC-135Rs experienced difficulties refueling the KC-10As, which caused the formation to slow down. The formation encountered headwinds stronger than forecasted. Perhaps the best explanation was that tanker crews routinely use air speed when planning their missions, while fighter crews rely on ground speed. The latter more accurately tracks a plane’s progress along a planned route, because it takes into account prevailing winds. Air speed equals ground speed only when no wind is present. Furthermore, during the final planning efforts no one from 48 TFW made it absolutely clear to the tankers that the bomber drop-off points in the central Mediterranean had to be reached on time. With drop-off points less than two hours away, urgent action needed to be taken to get the formation back on schedule. Agreeing with a recommendation from one of Westbrook’s staff officers, Forgan ordered the task force to increase speed and shave some distance off the planned route by cutting the next turn. These actions eventually made up the lost ten minutes, but the increased speed made the next refueling extremely difficult, since F-111F controls become very sensitive—or “goosey,” in fighter pilot jargon—at higher speeds. Venkus described the mood in the cockpits of the F-111Fs during this nerve-wracking phase of the transit to Libya: “As the delicate refueling maneuvers continued at airspeeds approaching four hundred knots, some F-111 crews silently cursed the tanker crews whom they mistakenly blamed for the entire problem. But they also breathed a sigh of relief as it became clear that they would make, though barely, their planned drop-off times. Because of the error, they would be operating at airspeeds much higher than normal for up to two hours. Flying night formation and refueling at these speeds was anything but fun.”

Off the coast of Tunisia the F-111Fs and EF-111As took their fourth and final pre-attack drinks from the tankers, still flying at twenty-six thousand feet. It was necessary to top off to ensure that the bombers had enough fuel to find their tankers in the dark or, if they were damaged during the raid, to fly clear of enemy territory. As each plane finished it dropped away from its tanker and started a gradual descent to its attack altitude of a few hundred feet.

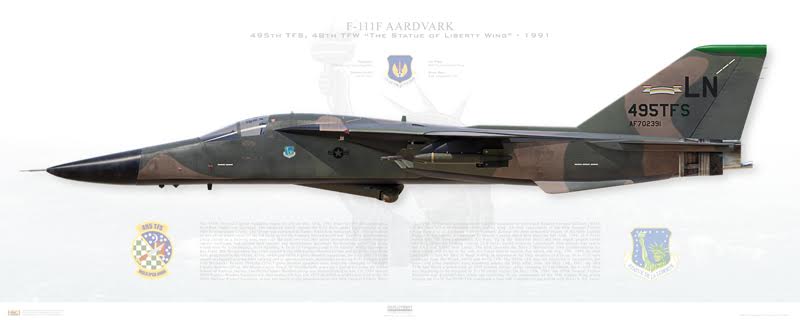

Meanwhile, back at Lakenheath at less than an hour before TOT, General Gabriel, Lt. Gen. John Shaud (an officer on Gabriel’s staff), and General McInerney entered the wing’s command post to monitor the attack. Until about 1500 U.K. time the command post had operated in a normal exercise mode. At two hours before takeoff British personnel were asked to leave and status boards containing operational information about the mission were uncovered. The Statue of Liberty Wing was now operating on a combat footing.

Puffy-11, the plane slated to be the first to cross into Libyan territory, left its tanker at 0114, Tripoli time. With five F-111Fs trailing behind it Puffy-11 rushed toward the Tripoli Military Airfield, more than 350 miles away. The other F-111Fs formed into their attack groups after topping off their tanks: nine planes for Aziziyah and three for Murat Sidi Bilal. As the bombers neared Tripoli some Air Force crews detected the silhouettes of SAM-busting A-7Es from the America moving into their firing positions. When he reached fifty miles from the beach the pilot of Puffy-11 turned off his navigation lights, armed his 500-pound bombs, and performed a final test of his plane’s systems. Once over land he would depend on the TFR to carry him safely over the desert landscape that was speeding below. At 0152 Puffy-11 crossed the beach. The plane was southeast of Tripoli, sneaking up on the airfield through the back door. Just moments before that the WSO in Puffy-11 had updated the plane’s inertial navigation system (INS) by locking on to an offset aim point (OAP), a natural or manmade geographical feature discernible on his radar. Updating the INS before the plane entered Libyan territory was crucial, because the F-111F’s navigational system has an error rate of a quarter mile every hour.

Meanwhile, equipment failure and pilot error had reduced the Aziziyah strike force to seven planes before the force reached the Tripoli target area. In Elton-44 the pilot completed the fourth refueling but did not break off until his tanker had turned toward its holding station located near Sicily. The pilot should have directed the tanker southward to facilitate his reaching the drop-off point on time. He realized that he could not reach the target on time without depleting his safety margin of excess fuel. He had no choice but to abort the mission, thus depriving the Aziziyah raiding force of one fully operational jet. Just before reaching Tripoli Elton-41 suffered a major equipment malfunction and it, too, had to abort. Additionally, one of the EF-111As, Harpo-72, experienced an equipment failure and was unable to carry out its mission.