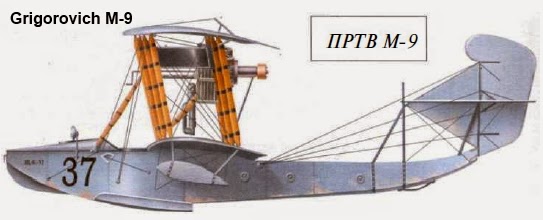

The German seaplane base on Lake Angern posed a threat not only to the aviation presence on Runo Island but also to the passage of Russian naval vessels in the gulf. The Russians responded quickly. Using the radio unit on Runo, the navy ordered the Second Bombing-Reconnaissance Squadron to send several bomb-loaded M-9s over the enemy seaplane station to see how much damage they could inflict. Joining Seversky for the perilous honor of attacking the Germans in August were lieutenants Diterikhs and Steklov, each of them accompanied on the right side of the M-9’s cockpit by a sergeant mechanic-observer who manned a single rotating machine gun. As in the case of the FBAs of the previous year, bombs were installed left and right of the hull and next to the pilot and sergeant. The flight from Runo to the gulf shoreline adjacent to Lake Angern went smoothly enough. As the three flying boats approached the enemy’s air base, however, their noisy, clattering Salmson engines warned the Germans of their arrival. Russian pilots and crews ignored the ground fire from small arms and at least one antiaircraft cannon as the three M-9 pilots focused on dropping ordnance on several station sheds.

The end of the successful pass over target resulted in gains and setbacks for the Russians. The good news was that although a number of German bullets and shell fragments had struck the M-9s, the aircrafts’ thick planked hulls had served as protective cocoons for pilots and sergeants; no metal fragments punctured the flesh of crew members. The bad news contained multiple parts. Lieutenant Steklov had to abandon the small detachment and flee to the northeast; an exploding shell had pocked-marked a radiator that then spewed out steam. Steklov would be saved. The M-9 carried two elongated radiators, one on each side of the liquid-cooled engine. The second intact radiator bought Steklov a few precious minutes of flight before the overheated engine froze and turned his flying boat into an unpowered glider. Fortunately for him, his motor enabled him to reach the gulf, where he was able to glide far enough from shore to be picked up safely by a Russian gunboat. Meanwhile, Diterikhs and Seversky circled back toward the enemy, intending to use their M-9 machine guns to damage the unmanned German seaplanes. But the pilots and sergeants soon discovered that their combat mission had actually just begun. Russian planes were entering a new and very dangerous phase of battle.

When the M-9s approached the German base, some seaplanes already had taken off to confront the Russians. Soon Diterikhs and Seversky faced a flight of seven Albatros planes with crews eager to seek revenge for the damage caused by Russian bombs. Thus began one of the great, epic air battles of the Eastern Front, which continued for at least an hour. It was prolonged in part because of the machine gun setups on the two opposing types of aircraft. With motor and propeller in front, the Albatros biplane was pulled through the air. The pilot sat behind the engine and behind the pilot sat the observer, who operated the machine gun from the second cockpit. But the only clear firing view for the German machine gun was in the arc between the two open sides of the seaplane. Firing straight ahead would kill the pilot, and even a slightly slanted forward aim would potentially destroy the struts and wire braces that supported the wings. By contrast, the M-9 crew sat in front of the engine and propeller, which pushed the craft through the air. As a result, the M-9 machine gun swiveled and the crew had a clear shot at anything in the 180-degree arc from side to side in front of it.

Besides being badly outnumbered by enemy planes, the Russians faced another problem. Due to the high drag produced by the hull, two radiators, and the Salmson engine, the M-9 had a top speed of only 110 kmh (about 68 mph). The Albatros C.Ia, with wheels for landing gear, flew 142 kmh (about 88 mph), but substituting pontoons for wheels, as the designer did, reduced the plane’s speed. Nevertheless, German seaplanes remained somewhat faster than Russian flying boats. Diterikhs and Seversky understood only too well that the odds were against them in guns and speed; a frontal attack against multiple German aircraft would be suicidal. Instead the Russian pilots initiated a flight of movement and maneuver that appeared to be an aerobatic dance in the sky. The pair wove their flying boats synchronously, in and out, with tight crossovers, creating an imaginary chain that proved difficult for the Germans to penetrate. Without the benefit of radio communications, German attacks lacked any type of logical coordination. Individual Albatros aircraft moved forward and back, exchanging gunfire with the M-9s. Seversky’s plane took more than thirty hits in the running gun battle, but the M-9 hull preserved its occupants, and all control surfaces remained functional.

The Germans were not so fortunate. Their designers had used wooden veneer as the covering for the Albatros fuselage. Bullets penetrated the covering and exposed the crew to deadly fire. As the aerobatic chain moved the air duel away from the enemy base and into the gulf toward Runo Island, Seversky’s M-9 shot down two of the German planes. All seemed to go well for the Russians until Diterikhs’ machine gun jammed, leaving the Grigorovich defenseless. When an Albatros moved forward to finish off the M-9, Seversky abruptly and fearlessly changed the heading of his plane to a collision course with the Albatros, but his object was not to initiate the taran. Instead, his machine gun opened fire, smashing bullets into the fore and aft cockpits, killing the crew and sending the Albatros into the Gulf of Riga. Seversky’s brazen action and the appearance of several more M-9s from Runo helped remind German pilots that their planes were low on fuel and they needed to return to their base at Lake Angern.

As might be expected, the one-legged aviator gained promotion to senior lieutenant (starshii leitenant). Tsar Nikolai II, in his role as commander in chief (glavnokomanduiushchii) of the Imperial Russian Military, awarded Seversky the Gold Sword as Knight of the Order of Saint George. It was Imperial Russia’s highest decoration and is sometimes equated with the top U.S. military decoration, the Medal of Honor. Seversky certainly demonstrated courage worthy of the decoration. Subsequent scouting reports, however, revealed that the Germans on Lake Angern quickly recovered from the M-9 bombs and the loss of the three Albatros aircraft. The enemy seaplane base posed a threat to Russian naval vessels, especially in providing air intelligence reports about Russian ships to German submarines in the Gulf of Riga. Regardless, the Baltic Fleet recommended that Stavka ask the EVK to conduct a significant bombing operation against the German seaplane station. The first thing the EVK did was to send a single Il’ia Muromets on a reconnaissance flight to the enemy base.

The plane’s commander, Lieutenant Vladimir Lobov, and his crew enjoyed a very successful intelligence run over the German air base. Sharp photographs clearly outlined sheds, hangars, barracks, and other facilities. A half-dozen Albatros aircraft took off and tried to intercept the Russian four-engine plane, but the bomber’s crew fired so many Lewis machine guns that the German aerial attack failed completely. On September 4, 1916 (N.S.), four Il’ia Muromets aircraft left the Zegevol’d Aerodrome near Pskov under the command of Lieutenant Georgii I. Lavrov. The detachment flew to Lake Angern and dropped seventy-three bombs on the German station, which housed seventeen seaplanes. Observers on the Russian aircraft confirmed the destruction and fires that consumed aircraft, hangars, and various structures. Multiple machine guns on the four reconnaissance-bombers suppressed enemy antiaircraft fire from the ground. As the Russians headed back to their aerodrome, they noted that columns of smoke were rising where the German seaplane station had been. The four large planes suffered no damage and returned safely from their mission to Zegevol’d.

The Il’ia Muromets aircraft assigned to the Stan’kovo Aerodrome near Minsk were equipped with less powerful, British-made Sunbeam engines that had a tendency to reduce the performance of the large reconnaissance-bombers. There was one IM Kievskii model that carried better Argus motors. In the summer and fall of 1916, the detachment carried out numerous bombing and photographing missions on behalf of the Russian Second, Tenth, and Fourth armies. With EVK aid these armies close to the center of the Eastern Front maintained a fairly stable combat line against the enemy. In order to distract the Germans in the north from a planned Russian offensive, the EVK decided to put on a show of force by sponsoring a major air attack against the headquarters of a German reserve division near the town of Boruna, just below the Russian offensive. The attacking force comprised four Il’ia Muromets planes and sixteen Morane-Saulnier French fighters, built by the Russian Dukh Company. The planes took off separately on September 25, 1916 (N.S.). Unfortunately, both the plans and their execution failed. The fighters missed linking up with the bombers and three of the larger aircraft never reached the target. One of the three Il’ia Muromets planes encountered German fighters supplied with explosive ordnance. An intercepted radio message later revealed that the Germans had lost three of their planes in the air battle; however, enemy bullets exploded one of the Russian bombers’ fuel tanks. The plane crashed, killing the entire crew, including its commander, Lieutenant Dimitrii K. Makhsheiev. Only the IM Kievskii completed the mission in triumph; overall, the show of airpower miscarried miserably.

Meanwhile, the offensive against the German forces on the Russian Northwestern Front simply failed. Occasionally, the Russian armies, under the leadership of General Aleksei N. Kuropatkin, nudged enemy troops back a short distance. Kuropatkin, the officer corps, and conscripted soldiers lost heart over Russia’s ability to defeat Germany. The Kuropatkin debacle was in sharp contrast to the performance of the four armies on the Southwestern Front commanded by General Aleksei A. Brusilov. After a crushing artillery barrage on June 4, 1916 (N.S.), Brusilov’s forces successfully attacked soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A major ingredient in the spectacular advance of the Brusilov offensive involved the EVK squadron that operated close to the Russian Seventh Army, which had spearheaded the attack against enemy troops. Led by Staff-Captain Aleksei V. Pankrat’ev, the EVK detachment photographed and secured important intelligence on the disposition of Austrian units and artillery. Performing two missions a day, the large planes also bombed railway stations, railroad beds, warehouses, and towns occupied by enemy soldiers. When the Russians occupied new territory, ground troops saw first-hand evidence of the destruction caused by Il’ia Muromets aircraft and heard tales of how Austrian troops abandoned in panic their positions after a Russian bombing run.

In action by single-engine planes, it should come as no surprise that Russia’s top two ace pilots flew in the very active Southwestern Front, where aviation and aviators were held in high esteem by Brusilov, the front’s offensive-minded commander. As noted earlier, in 1915 a type of Russian fighter aircraft emerged that employed a machine gun in the front of a pusher-type aircraft. A Grigorovich M-5 flying boat of 1915 also could carry that weapon, and in 1915–1916 a machine gun could be placed on the top wing of a Nieuport biplane that was pulled through the air by its propeller. The formal creation of fighter detachments with six aircraft each took place in March 1916 under Order No. 30, signed by Tsar Nikolai II. By August of that year, there were a dozen fighter squadrons, one for each of the twelve Russian armies. The use of such detachments could not begin to protect all aircraft that performed reconnaissance missions over enemy forces; nevertheless, on the Russian Southwestern Front, the country’s second-highest ace pilot, Vasili I. Ianchenko, was credited over time with sixteen enemy kills.

As a youth, Ianchenko studied mathematics and mechanical engineering at the Saratov Technical School, graduating in 1913 at age nineteen. His enthusiasm for airplanes prompted him to take flying lessons, and when war broke out, in 1914, he volunteered for military aviation service. Interestingly, because he had entered the army from the lower-middle class, failed to attend a military school, and had begun army life as a private (riadovoi), he never attained a rank higher than ensign (praporshchik). Over the winter of 1914–1915 he attended ground school at the Saint Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. Once he completed the aeronautics course he received orders to travel by train south to the Sevastopol’ Aviation School. In the spring and summer of 1915, he finished military flight training there on the French-designed, Russian-built Morane-Saulnier monoplane. That fall he transferred to the Twelfth Air Corps Squadron, where he demonstrated such outstanding skills as a pilot that he received orders to attend an air school in Moscow where he learned to fly an advanced Morane-Saulnier fighter. After finishing that course early in 1916, he went to a squadron in the central regions of the Eastern Front. Ianchenko flew ten combat missions, but after hearing about the tsar’s order he requested transfer to Russia’s first formal fighter detachment—the Seventh Fighter Squadron, attached to the Russian Seventh Army. He joined what proved to be a busy squadron, preparing for the Brusilov offensive. Between April and October 1916, he flew eighty combat missions and became one of Russia’s most decorated pilots.

Russia’s top ace pilot was Aleksandr A. Kozakov, who had amassed twenty confirmed kills. Somewhat older than other pilots, he was born in 1889, the son of a nobleman. He attended military schools in his youth and graduated from the Elizavetgrad Cavalry School. The junior lieutenant (kornet—cavalry rank) spent his first years in a horse regiment, but transferred to aviation as a senior lieutenant (poruchik—cavalry rank) in 1914. After completing ground school and flight training in October, he was assigned to the Fourth Corps Air Squadron, north of Warsaw, where he flew the two-seat Morane-Saulnier monowing reconnaissance plane. Near the end of the 1915 Great Retreat he was promoted to staff-captain (shtabs-rotmistr—cavalry rank) and appointed to head the Russian Eighth Army’s Nineteenth Corps Air Squadron on the Southwestern Front. Early in 1916, on his own initiative, Kozakov had a Maxim machine gun installed on the top wing of his Nieuport 10 biplane. After multiple kills, he became the leader of the three Russian Eighth Army Corps aviation detachments that formed the First Combat Air Group. To protect the Eighth Army’s recent victory in the skies over the Austrian city of Lutsk, a major railway hub, the combat group received special Nieuport 11 and SPAD SA.2 fighters imported from France.

Austria hoped to regain Lutsk and destroy or damage railway facilities, so Kozakov and the First Combat Air Group engaged numerous Austrian fighter and scouting aircraft. The Austrian Brandenburg plane actually had been designed by a German, Ernst Heinkel, and originally was built in Germany by the Hansa und Brandenburgische Flugzeug-Werke. Moreover, Germans often piloted the “Austrian” airplanes. The Russians’ effort succeeded. In 4 months, they captured 417,000 Austrian prisoners, 1,795 machine guns, 581 artillery pieces, and 25,000 square kilometers (15,500 square miles) of territory, according to an enthusiastic account of the Brusilov offensive written 15 years later by Russian general Nicholas N. Golovine (an anglicized version of Nikolai N. Golovin) in The Russian Army in the World War. None of the Allied powers could match the success of the Russian attack. The Austrian military nearly collapsed; it had to end its own offensive against Italy by transferring 15 divisions to the Eastern Front. Germany, fearful that the Austro-Hungarian Empire might sue for peace, sent 18 divisions from the Western Front and 4 reserve divisions that had been housed in Germany in order to bolster Austrian forces and keep them in the war.

Airpower made an observable contribution to the success of the Brusilov offensive. The EVK used extensive photography to reveal fully the enemy’s defensive order of battle. The Russian Southwestern Front employed 17 squadrons, comprising 90 pilots and 88 single-engine aircraft. (The last two numbers clearly illustrate the Russians’ chronic problem of not having enough pilots and planes to operate the expected standard of 6 airplanes per squadron.) Nonetheless, Russian fighters hampered the ability of Austrian air reconnaissance to identify the point of Russian attacks; the fighters also tried to protect Russian aircraft that carried out intelligence-gathering missions. This combination of scouting and EVK photography enabled Russian artillery to suppress and destroy the opponent’s defenses and to cause more damage with fewer cannon. During the breakthrough period of the Russian advance, the 17 air squadrons carried out 1,805 combat missions. Peak activity occurred in August 1916, when pilots completed 749 flights under battle conditions. By October the Brusilov offensive stalled, partly because of Russian casualties, autumn rains, and the fact that the Austrian line of defense had been greatly strengthened by the large number of new Austrian and German military divisions. Finally, the static nature of the Southwestern Front in the fall of 1916, coupled with the long-term stability of the Northwestern Front, explains the rapid expansion in the number of balloon detachments that year. By December there were some 73 balloon observer stations in 13 balloon divisions operating from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. Although balloons often were subjected to enemy gunfire, they played an important role in observing activity in the forward lines of German and Austrian troops.

The achievement of Russian armies in advancing into Austrian Galicia was more than matched by the power and work of the Black Sea Fleet in checking the Central Powers and turning the sea into a Russian lake. First, the fleet continued to send hydrocruiser task forces and their shipborne flying boats to intervene and disrupt the transit of coal by attacking Turkish steamers and sailing ships. The effort proved so thorough that at times Turko-German ships, including the Goeben and Breslau, lacked the fuel necessary to steam into the Black Sea. By December 1916 the Russians had sunk or captured more than a thousand Turkish coastal craft. On one of the hydrocruiser visits to Zonguldak the following February 6 (N.S.) fourteen Grigorovich aircraft dropped thirty-eight bombs on the ex-German collier Irmingard—the largest vessel to be lost to an air attack in any theater of battle during the Great War. Second, task groups repeatedly bombarded the Bulgarian port of Varna. On August 25 (N.S.) the aircraft carriers Almaz, Aleksandr, and Nikolai sent nineteen planes into the harbor to bomb German submarines.

Finally, in 1916 the army-dominated Stavka finally decided to take a step that it had refused two years before. Vice Admiral Andrei A. Eberhardt, an aggressive commander, had wanted from the beginning of the war to prepare the Black Sea Fleet for amphibious operations should the Ottoman Empire become a member of the Central Powers. Even though Stavka had mistakenly predicted that the Turks would remain neutral, the army did not want to commit a substantial number of soldiers for waterborne military action. What we now call “if history” is fiction, of course, but if the Russian army had approved the preparation of amphibious troops with the Black Sea Fleet, such a force might have collaborated with the Allied attack at Gallipoli. British and French warships bombarded the peninsula in February 1915 and later landed troops there. A major amphibious assault by Russian soldiers disembarked from the Black Sea near Constantinople might have led to the occupation of the Turkish capital, knocked the Ottoman Empire out of the war, and brought Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania into the conflict on the side of the Allies. Black Sea ports would then have been opened to safe and copious trade and the entire chemistry of the war would have been altered.

The Black Sea Fleet and its hydrocruiser task forces housing flying boats also assisted the Imperial Russian Army in its Caucasus campaign against the Turks. The navy and its Grigorovich aircraft interrupted, captured, or sank Turkish ships that carried troops and supplies eastward to the front against Russia. When an army-sized Turkish relief force under Vehip Pasha marched along the northern coast of Anatolia, Russian war vessels and aircraft harassed the troops and damaged supply columns, leaving the relief force no option but to retreat. Then, in March 1916, Stavka finally agreed to an amphibious operation against the Ottoman Empire. The dreadnought Rostislav, gunboat Kubanets, 4 torpedo boats, 2,100 soldiers (shipped on 2 transports), and 3 flat-bottomed minesweepers entered the small Atina harbor. Just behind Turkish lines, the amphibious exercise caught Russia’s enemy in a surprising pincer that enabled the Russian Army to advance westward into the Turkish port of Rize on March 6 (N.S.).

The Black Sea Fleet became heavily involved in augmenting Russian troops and supplies for the Caucasian Front. On April 7 (N.S.) approximately 16,000 Cossack soldiers were shipped to Rize on 36 smaller transports, with 8 flat-bottomed Elpidifor craft for the amphibious coastal landing stage. The substantial number of infantrymen had the protection of a dreadnought, 3 cruisers, and 15 torpedo boats. Three hydrocruisers holding 19 flying boats accompanied the naval task force. Aircraft provided a reconnaissance screen against German submarines and Turko-German warships. The additional troops enabled the Russians to stall and then defeat a serious Turkish counterattack. By April 19 (N.S.) the Russians had pushed the enemy westward and occupied the major Turkish port of Trabzon (anglicized as Trebizond). In the second half of May and early June, the Black Sea Fleet then used two convoys to transfer to Trabzon the 123rd and 127th infantry divisions, which included more than 34,000 men. Once again hydrocruisers used cranes to unload M-9s to the sea—planes that then flew scouting missions to help protect the convoys from enemy ships and U-boats.

In July 1916 Vice Admiral Aleksandr V. Kolchak replaced Eberhardt as commander of the Black Sea Fleet. It would be nice to say that Eberhardt deservedly retired with honor, but the reality is that in both government and military, administrators and officers often engaged in politics and infighting to gain preferred appointments. Nevertheless, as a rear admiral Kolchak had been an excellent chief over the Baltic Sea’s destroyer force, and he clearly valued aircraft now. While Eberhardt had established naval air stations at Batum, Rize, and Trabzon, Kolchak tripled the number of airplanes in some cases. On September 11 (N.S.) he dispatched flying boats to bomb the Bulgarian port of Varna as well as the Eukhinograd German submarine base. In August he also began secretly laying hundreds of mines around the Bosporus and later Varna; the minefields were constantly augmented, so that in essence the Central Powers were denied access to the Black Sea. It would be eleven months before the Breslau dared to steam through the Bosporus. Finally, Romania’s entry into the war as a member of the Allies in 1916 led to that country’s defeat by a German-Bulgarian-Turkish army under Mackensen. On December 16, 1916 (N.S.), Romania’s main port of Constanta also was mined. The only Turkish vessels remaining in the Black Sea were smaller sailing ships berthed in lesser ports along the coast of Anatolia.