Before exploring aviation’s contribution to the Russian battlefield in 1916, it is important to consider some of the differences between the Eastern and Western fronts. The Western Front was much shorter, only about 400 miles, yet its combat zone contained a significant concentration of British, French, and German soldiers, accompanied by a massive number of artillery and machine guns that put in harm’s way almost every square yard of the elaborate trench system that ran from the North Sea southeastward to neutral Switzerland. At the same time, this much smaller front was home to far more aircraft than were assigned to the Eastern Front. In 1916 the French and Germans each maintained an inventory of planes that approached 1,500. During the Battle of the Somme, the British employed not just 4 air detachments, as the Russians might have done, but more than 27 squadrons, equipped with 410 aircraft. In short, there was a big difference between the air activity on the Eastern and Western fronts. The Germans, for example, claimed 7,067 air combat victories in the West, but they reported only 358 triumphs in the East against Russian pilots. In the West, when weather permitted, hundreds of air missions and a dozen dogfights occurred every day, with bombers, scouting craft, and fighters on both sides. Meanwhile, in the much more expansive Eastern Front, which extended from Riga in the north to Czernowitz (near Romania) in the south, there were some minimally contested areas that never drew a single airplane from either side.

The amazing thing about the Eastern Front is that by March 1916 Chief of Staff Mikhail V. Alekseev succeeded in rejuvenating twelve Russian armies. Facilitating his rebuilding effort was the Russian industrial expansion, which led to the manufacture of military hardware that put the Russian armies on a more competitive footing with enemy forces. But three critical factors enhanced the larger picture for the Russians. First, German and Austrian troops killed or captured 2.5 million Russian soldiers, whom Petrograd had to replace by enlarging the draft. Such horrific losses deeply undermined the morale of Russian troops, especially those who faced German armies in the north. Unsurprisingly, offensives on the Russian Northwestern Front faltered in 1916. Second, industry’s massive effort to replenish war materiel caused disastrous problems for the economy. Russian cities could not barter machine guns for grain and other agricultural products. Collapse of the urban-rural exchange system, coupled with a diminished supply of fuel through industrial use, ignited the Russian Revolution in 1917. Third, Russia depended on foreign imports for the war—and not just airplanes and aircraft engines. Between 1914 and 1917, for example, Russia imported 836 million dollars’ worth of products from the United States—then a fortune—including airplanes, aircraft engines, armored cars, barbed wire, boots, copper, cotton, dyes, electric machinery, gunpowder, harnesses, horseshoes, howitzer shells, lead, leather, locomotives, machine tools, medicines, nickel, rails, railroad cars, rifles, rubber, saddles, shrapnel, surgical instruments, trucks, wool, and zinc. Together, these imports and Russian industrial output helped create an army in 1916 that was better equipped than at any other time during the war.

In goods directly related to aviation, Russian industry built over six times more aircraft in January 1916 than it had in August 1914. The original monthly production for each of the 5 major Russian firms was 25 planes for Russo-Baltic; 35 for Lebedev; 40 for Anatra; 50 for Shchetinin; and 60 for Dukh. Six smaller workshops constructed and added 6 to 8 airframes to the monthly base of 217. As might be expected, the number of aviation laborers, ranging from those assembling airframes to those building propellers, more than doubled in 1916 to 5,029 workers. Even so, the shortage of engines continued; the French motor subsidiaries in Russia did not come close to manufacturing enough aircraft engines to match the number of airframes being produced. By year’s end France, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States had exported to Russia via Arkhangel’sk or Vladivostok some 2,500 aviation engines, which greatly (but not completely) helped meet the empire’s requirements. By year’s end these countries also exported about 900 assembled aircraft to Russia. Despite these imports and Russia’s increased domestic production, the problem of supplying the Russian military with enough aircraft remained because monthly loss rates often approached 50 percent. Regardless, each of the 12 armies fielded several squadrons of planes, and heavy combat areas received additional special bombing and fighter aircraft detachments.

The Russian air forces and those of several other belligerents as well appeared to reach a degree of autonomy during that period. Before war’s end, Great Britain, for example, combined its Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service to form the Royal Air Force (RAF), under Major General Hugh Trenchard as chief of staff. Theoretically, the RAF held the same status as the British army and navy. By mid-1915, Grand Duke Aleksandr commanded the Directorate of the Military Aerial Fleet. On November 24, 1916, with Order No. 1632 from the chief of the General Staff, the grand duke also took complete charge of all Air Force inspectors. In the case of Russia, however, true autonomy for aviation existed more on paper than in reality. In effect, aircraft operations continued to be administered by army field generals and navy sea commanders. (As mentioned previously, pilots could not be promoted above the rank of army captain. The lone exception was in the EVK.) When the Great Retreat forced Stavka to evacuate Baranovichi for Mogilëv, the grand duke shifted his headquarters to Kiev. Naturally he kept in touch with Stavka, but his autobiography reveals that he increasingly spent time interacting with the Romanov family and expressing concern about the tsar and the tsar’s future.

The grand duke admitted that he was in Petrograd quite frequently; he could justify the visits there, since three large aircraft manufacturing firms operated in the empire’s capital city. He remembered: “Each time I came back to Kieff [Kiev] with my strength sapped and my mind poisoned.” From his vantage point the rumors that were spreading across the capital city about Tsar Nikolai II and his wife, Aleksandra Feodorovich, were downright ugly and wicked. The grand duke noted false rumors alleging that the tsar had become an alcoholic; that he took Mongolian drugs that clogged his brain; that his prime minister was in league with German agents in neutral Sweden; that his German-born wife favored Russia’s defeat; and that she had had sexual relations with the uncouth and self-proclaimed holy man, Grigorii E. Rasputin. Rasputin’s unsavory reputation, though, was very real and well-deserved. He argued that salvation followed sin, and he sinned incessantly. He exerted influence over the royal couple—including their appointment of some of his “favorites” to high ministerial positions—because his calming powers had saved the couple’s only son and heir to the throne from potentially fatal episodes of severe bleeding due to hemophilia. Later that year Grand Duke Aleksandr said he had “felt glad to be rid of Rasputin” when the “holy man” was murdered after dinner in the home of Aleksandr’s daughter, Irina, and son-in-law, Prince Feliks Iusupov. But Rasputin’s death had come way too late to help save the Romanov dynasty.

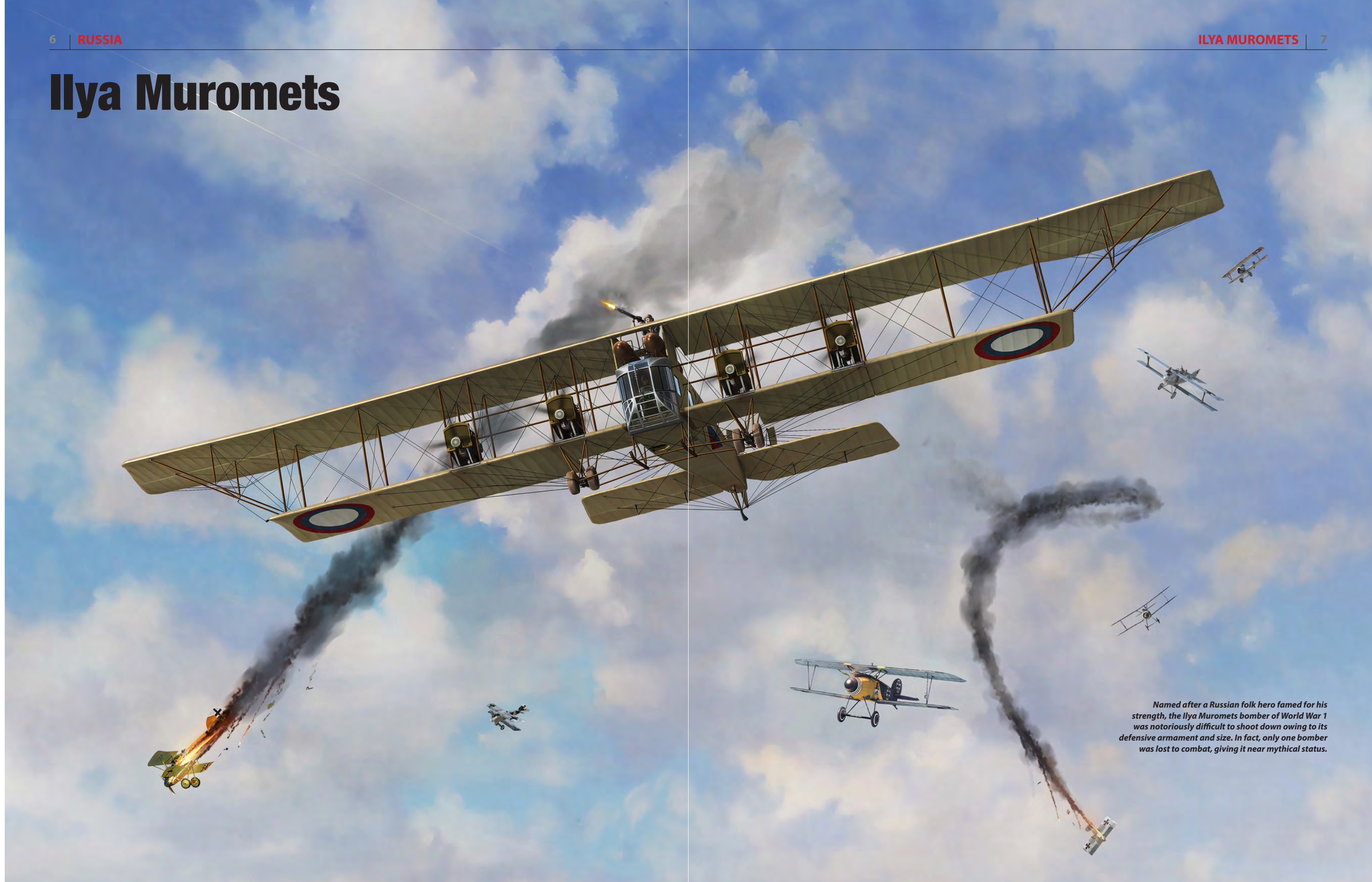

The grand duke’s effectiveness as head of the Directorate of the Military Aerial Fleet was limited by his focus on Rasputin and the problems of the tsar. At the beginning of 1916, the Russian air force had reached the serious level of 53 squadrons—42 army corps, 8 fighter corps, and 3 special detachments to protect Imperial residences. The grand duke’s distance from Stavka’s headquarters and his uneven attention to aviation issues prevented the directorate from moving toward greater autonomy for military aircraft. And even if the grand duke had wanted to create a semi-independent air force, Stavka continued to prevent him from elevating the rank of pilots above the level of captain. Fortunately, the grand duke had nothing to do with the EVK, which he disliked; it remained in the hands of Stavka. The Il’ia Muromets aircraft, formidable weapons for their time, conducted 442 combat missions during the war. The reconnaissance-bombers destroyed 40 enemy planes, took 7,000 high-quality photographs of enemy positions, and dropped more than 2,000 bombs. By the end of 1916, their varied engines could be rated as high as 225 hp; they carried some armor plating, were equipped with protected fuel tanks, and housed 7 or more machine guns and occasionally a small-bore, quick-firing cannon. The plane represented an early version of what Americans would later call the B-17 flying fortress.

Once the EVK headquarters had been established at Zegevol’d, close to Pskov but not far from Riga in the north, Russian authorities created two other detachments for the 1916 campaign that were close to the middle and south of the Eastern Front—Stan’kovo, near Minsk, and Kolodziievska, near Tarnopol in the region of Galicia. It is easy to argue that Zegevol’d was the most important aerodrome for an EVK detachment. If the Germans were to capture Riga, the enemy would inherit a direct rail line to the empire’s capital in Petrograd. Riga’s extremely important strategic position helps explain why the EVK headquarters was stationed near that city. Understandably, Stavka wanted to do everything necessary to keep the Germans from taking Riga, which seemingly was the objective most desired by General Ludendorff, who planned the German campaign along the Baltic shore. Nevertheless, by the end of the German offensive enemy troops ended up stalled and dug in about twenty-five miles from that key urban center. During the later winter of 1916 when weather permitted the EVK detachment at Zegevol’d began regular photographic reconnaissance in Courland and the southwestern shore of the Gulf of Riga detailing the German positions for the Russian Twelfth and Fifth armies.

In April 1916 the photographs reinforced the need for the EVK detachment at Zegevol’d to repeat its bombing of the railroad station in Courland at Friedrichstadt, which supplied the Niemen Army. The EVK sent the tenth version of the Il’ia Muromets Model V, piloted by Lieutenant Avenir M. Konstenchik. Born the son of a Russian Orthodox priest in the city of Grodno (now in Belarus), Konstenchik completed his basic education by attending a Russian Orthodox seminary. Yet the young man chose not to continue his seminary studies, which would have led to priesthood, but rather attended a special military academy. After graduation, he served in the Thirty-Third Infantry Regiment, then transferred to aviation and became a pilot. His first aviation assignment took him to the air squadron attached to the Brest-Litovsk Fortress. In September 1914 Konstenchik was selected to be one of the first pilots to learn how to fly one of the ten Il’ia Muromets aircraft ordered by the military.

Those joining Konstenchik on the April 13 (O.S.) mission included the deputy commander, Lieutenant Viktor F. Iankovius; artillery officer and reconnaissance photographer, Lieutenant Georgii N. Shmeur; machine gunner, Sergeant Major Vladimir Kasatkin; and engine mechanic, Sergeant Major Marcel Pliat. Pliat had been assigned under an exchange program with France designed to help cement the military alliance between the two countries and enable them to share air combat techniques. Besides maintaining and repairing engines, Pliat manned the tail machine gun. He also was a special EVK member because of his Franco-African background. He proved to be the savior of the plane and crew in keeping a couple of Sunbeam motors in operation during flight. Imported from Great Britain, each Sunbeam liquid-cooled engine produced a rating of only 150 hp. Fortuitously, Sikorsky’s redesign of the big plane resulted in a craft that was so aerodynamically improved that it could carry crew and bombs to an altitude above 7,800 feet.

Being able to fly at higher altitudes kept the reconnaissance-bomber well above small-arms ground fire from the enemy. The first pass over the large Daudzevas railroad station near Friedrichstadt went smoothly enough as the Il’ia Muromets dropped a half dozen of its thirteen bombs. During the return pass to finish the bombing run and take photographs, the Russians discovered how much the Germans valued the huge station and its warehouses. The enemy protected the rail facilities with guns that fired exploding ordnance that could reach high-altitude aircraft flying at 15,000 feet. A shell exploded near the cockpit; metal fragments from the shell-shattered glass wounded Konstenchik and damaged three of the four engines. Shrapnel also struck the hands of the artillery officer and shattered the camera that he was holding. When the pilot was hit with pieces of metal, he fell from his seat and pulled the steering column backward. The result was an abrupt climb, which caused a stall. As the plane dropped toward the ground, Iankovius slid into the pilot’s seat. He was able to get the plane out of the stall and stabilize flight at about 3,000 feet as Kasatkin applied emergency first aid to Konstenchik. Fortunately, Pliat, in the plane’s tail, held on tightly to save himself from falling away from the plane as it dropped during the stall; when the aircraft recovered from its near-fatal descent, he worked his way forward through the fuselage to join the other crew members.

Pliat then climbed out on the wing and, ignoring grave danger to himself, managed to keep 2 of the plane’s 4 engines running. Limited power forced the Il’ia Muromets to continue flying only at a low altitude of 1,000 meters [about 3,075 feet]. For 26 kilometers (a little more than 16 miles) the plane flew over German troops, who took pleasure in firing rifles at the Russian plane, wounding crew members. When the bullet-riddled aircraft landed at a Russian aerodrome and came to a stop, its right wing dropped completely to the ground. Despite such obvious combat damage, the plane’s safe landing only added to the legend of the miracle survivability of the Il’ia Muromets. This mission resulted in a series of awards: Lieutenant Konstenchik received the Order of Saint George, Fourth Degree; Lieutenant Iankovius, the Sword of Saint George; and Sergeant Major Pliat, the Cross of Saint George. Sergeant Major Kasatkin received a commission as an officer.

Meanwhile, several of large EVK planes continued to aid the Russian Twelfth and Fifth armies in their defense of Riga by photographing and bombing German targets of opportunity. Then, in July 1916, came several extraordinary events that would have a major impact on the EVK. First, future ace pilot Alexander Seversky returned to combat duty—minus a major portion of his right leg—as part of Second Bombing-Reconnaissance Squadron. Although the squadron was headquartered at the naval air station at Zerel on the southern point of Ösel Island’s Sworbe Peninsula, it established an auxiliary base on tiny Runo Island, about forty-five miles east-southeast of Zerel, near the center of the Gulf of Riga. With Runo Island as a base, Russian pilots searched intensely for German submarines. In one of Seversky’s first scouting flights from Runo, in a Grigorovich M-9 flying boat, he shot down a German Albatros C.Ia. The German land plane had been converted to a seaplane by replacing its wheels with floats. The victory was a jolt to Seversky, his squadron, and the Baltic Fleet. It meant that the Germans had some type of seaplane base near the Gulf of Riga. Subsequently, another squadron member in an M-9 spotted an Albatros C.Ia seaplane taking off from Lake Angern. Less than a mile into the interior, the lake parallels the western shore of the gulf for ten miles. The Germans loved it because their seaplane base was completely invisible to vessels of the gulf’s Imperial Russian Navy.