August Euler & His Airplanes 1908 – 1920 Volume 1: A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes (Great War Aviation Centennial Series) Paperback – October 23, 2018

by Michael Düsing (Author), Dr. Hannes Täger (Translator)

The first German manufacturer of aircraft appeared in 1908 in a field near Darmstadt. The Euler Works, as it was originally known, had been founded by August Euler, who made bicycles and automobiles. It was the manufacture of these forms of transport that brought him into contact with other German and French metal firms, among whom were Delagrange, Blériot and Farman, all of which were aircraft manufacturers. August Euler had learned to fly some years earlier and held licence No.1 in Germany. He approached the French company Voisin with an offer to build the Voisin aircraft in Germany under licence, but the French Government stepped in and prevented it. It is possible they had already seen signs of an impending conflict between the two countries.

August Euler had built and flown one of the first powered aircraft in Germany. He had also devised a method of aiming a machine gun without special sights, which was effected by the aircraft’s controls. He applied to the Imperial Patent Office for a patent, which was accepted and was awarded the patent No. 248601. Euler offered his patent to the German War Ministry, who turned it down almost out of hand. In a memorandum, after seeing the patent, Major Siegert of the General Staff wrote:

One of the major disadvantages of the biplane with the engine at the nose is using an automatic weapon. The guns are prevented from firing forward by the propeller, to the sides by the rigging wires, to the rear by the pilot, above and below by the wings.

Undaunted, August Euler went ahead with his plans to build an aircraft, and it was discovered later that, encouraged by the German Army, he built a factory on the field. It has to be remembered that aircraft manufacture was at the time in its infancy, and the factory consisted of a design office fitted with two drawing boards, a workshop fitted out with lathes, sanders and benches and an assembly shop measuring 50 metres long, 20 metres wide and 9 metres high. Euler had obtained the field after writing to General von Eichhorn, commander of the 18th Army Corps in Darmstadt, offering to train some of his officers as pilots in exchange for a field and hangar. The German War Ministry agreed, on the condition that he pay for the construction of the hangar and that he allow the Army unlimited access to the field. In return, he could have the field rent-free for five years and a promise that other aircraft manufacturers would not be allowed to build aircraft on the field during this period.

August Euler drew up plans for the hangar, and realised that he was unable to obtain enough labour to construct it without importing labour from nearby towns. He wrote to General von Eichhorn explaining the problem and suggested using the Army, for payment of course, to build the hangar and its workshops. Von Eichhorn agreed and arranged for the 21st Nassau Pioneer Battalion to be sent to the field. In return, Euler had to provide all the material, transportation and housing for the battalion and pay the battalion 2,400 marks. In less than four months the building was completed, and the manufacture of the first aircraft begun.

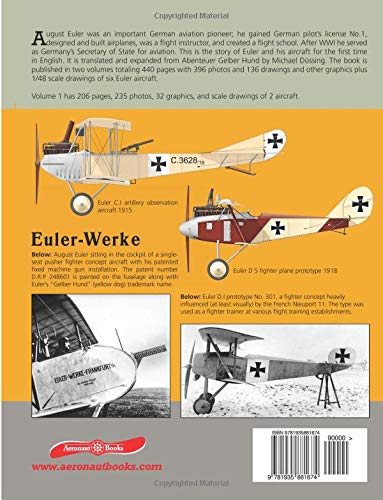

On 15 December 1911, August Euler opened up a new factory in Frankfurt-am-Main, which had five large hangars and accompanying workshops capable of producing thirty aircraft at one time. This was a welcome announcement to the German military machine because of the Moroccan crisis the previous summer that had sent warning bells of unrest throughout the Middle East. The first aircraft produced by the company was a two-seat pusher known as the Gelber Hund (‘Yellow Dog’), which was fitted with a revolutionary machine gun installation in the nose. At the same time, a proposal had been put forward regarding mounting a machine gun that would fire through the propeller hub. It was not the success Euler hoped for and it failed to impress the German War Department and gain any contracts. Again it was Major Siegert who, in another of his memorandums, wrote:

The idea of mounting a machine gun within the propeller hub is an affectation, as is the alternative of coupling the firing mechanism to the propeller’s rotation, which would make it possible to fire bullets between the propeller blades when they are in the correct position. The objection to mounting the gun barrel within the hub of the propeller is the same as to any gun position which is fixed along the longitudinal axis of the aircraft: the pilot is forced to fly directly at the enemy in order to fire. Under the circumstances this is highly undesirable. With this form of gun installation any superiority in speed will be nullified when weapons are activated.

Once again this kind of comment only highlighted the resistance to change by the military hierarchy which was placing a stranglehold on German military aviation. It was to take a war to release it and, ‘necessity being the mother of invention,’ enormous strides were made within a very short time.

The German aircraft manufacturers found it easier in the early stages to copy existing designs of aircraft and August Euler was no exception. He copied the successful Voisin model. He did this by buying one of the models, and infuriated the French company because he had no licence to do so. Problems arose because the German engineers lacked the detailed knowledge required for the construction and the use of the materials. The copy produced was substantially inferior to the original.

In April 1912, August Euler suggested to one of his former pupils, Prince Heinrich of Prussia, that the creation of a National Aviation Fund would help the development of the German aircraft industry, which in turn would help develop German military aviation. Prince Heinrich, who was the patron of German aviation, welcomed the suggestion and under his patronage a committee was formed with high-ranking members of the banking and political fields. Despite the influential support of Prince Heinrich, over the next two years the development of the German aircraft industry was notably slower than that of the Army manufacturers.

Euler, unlike many of his counterparts and because of the various positions he had held in the National Aviation Fund and the Aviators Association, was in a strong financial position. He also had an overestimation of his own importance and it was this that brought him into conflict with the Army, the very people to whom he was trying to sell his aircraft.

In a letter to Major-General Messing of the General Inspectorate, Euler accused them of refusing to buy the Gnome engines he was building under licence from the French company, while encouraging another German manufacturer, Oberursel, to obtain a production licence from the Gnome Company to build the engine. This acrimony had started some time earlier, when one of Euler’s aircraft had crashed, killing the two Army officers on board. The Army tried to get Euler to admit that there were problems with the aircraft, which he refused to do, resulting in Captain Job von Dewall, the commanding officer of the air station at Darmstadt, carrying out exhaustive examinations of all the aircraft that came out of the Euler factory there.

Accusing von Dewall of carrying out a vendetta against him, Euler was prompted to write a letter to Messing and attempted to use his influential friends to resolve the matter. However, his money and powerful friends cut no ice with the Prussian Army, and Euler was forced to lower his price for the fourteen aircraft he had supplied, from 348,750 marks to 247,300 marks. In fact, he had no choice: he was about to lose over half his workforce, and was even thinking of selling his factories. Euler’s pride was shattered, and such was the power of the Prussian Army that it forced Euler to carry out licensed production.

During the First World War, Euler continued to design and produce aircraft, but he was now way down the order of manufacturers and being overtaken by Rumpler, Aviatik and Albatros. He joined forces with an Austro-Hungarian engineer by the name of Julius Hromadnik and together they designed a number of different types of aircraft, including four triplanes. The first of these was the Euler Dreidecker Type 2, powered by a 160-hp Oberursel U.III engine and designed primarily as a trainer, which appeared in March 1917. One month later the Euler Dreidecker Type 3 appeared, this time powered by a 160-hp Mercedes D.III engine. A move to using a rotary engine produced the Euler Dreidecker Type 4, powered by a 180-hp Goebel Goe.III rotary engine. None of these triplanes attracted the military and only one of each was built.

In September 1917 the Euler Vierdecker, a quadruplane, appeared. It was powered by a 100-hp Oberursel U.I rotary engine, but lacked any sort of performance that would have attracted the German military into placing an order. Using some of the better points of the Dreideckers, Euler produced a biplane version, the Doppledecker Type 2, powered by a 160-hp Siemens-Halske Sh.III counter-rotating engine. There had been a Type 1, but it had been purely experimental and amounted to nothing, as did the Type 2.

The end of the war brought about the demise of the Euler-Werke and the company disappeared, like many others, into obscurity.

- Euler B.I – reconnaissance

- Euler B.II – reconnaissance

- Euler B.III – reconnaissance

- Euler C – reconnaissance pusher

- Euler D.I – fighter, copy of Nieuport

- Euler D.II – fighter

- Euler D – fighter (possibly D.III)

- Euler Dr.I – triplane fighter

- Euler Dr.2 – triplane fighter

- Euler Dr.3 – triplane fighter

- Euler Dr.4 – triplane trainer

- Euler Pusher Einsitzer – fighter

- Euler Quadruplane – fighter