Having been reinforced with several French ships, Lyons took his light squadron into the Sea of Azov the following day. As one contemporary observer, Hamilton Williams, wrote:

It was like bursting into a vast treasure house, crammed with wealth of inestimable value. For miles along its shores stretched the countless storehouses packed with the accumulated harvests of the great corn provinces of Russia. From them the Russian armies in the field were fed; from them the beleaguered population of Sevastopol looked for preservation from the famine which already pressed hard upon them.

Furthermore, on the Kerch Straits themselves, the towns of Kerch and Yenikale contained coal stocks amounting to 12,000 tons, which would keep the Allied fleet going for a considerable period without recourse to its own colliers.

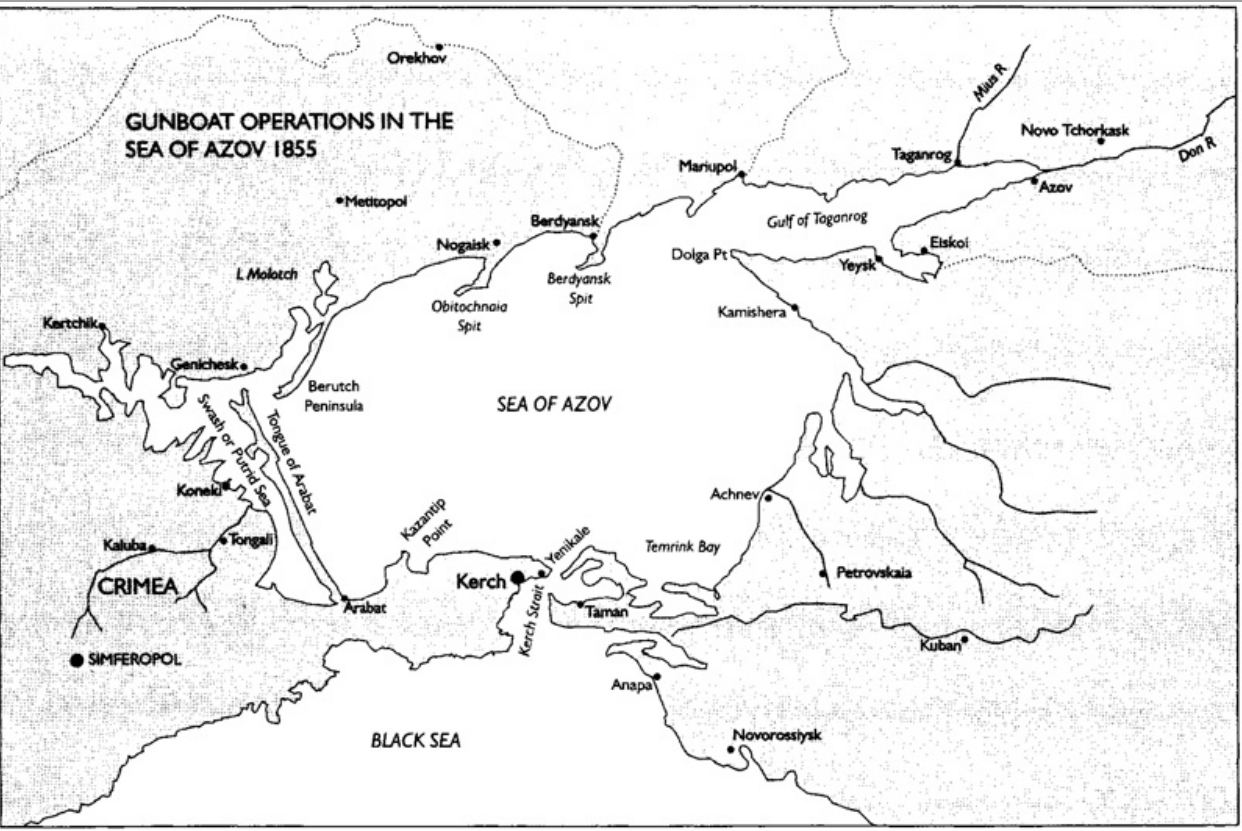

Lyons’s ships proceeded to raise hell across the widest possible area. One was sent to cruise off the mouth of the Don, while two more were detached to Genichesk at the entrance to the Swash or Putrid Sea, a stretch of water separating the north-eastern coast of the Crimea from the Sea of Azov proper by a thin 70-mile-long spit of land known as the Tongue of Arabat. On 28 May the rest of the squadron bombarded Fort Arabat, situated at the mainland end of the Tongue. The engagement lasted some 90 minutes, at the end of which the defence works were wrecked by an internal explosion. Next day the squadron moved to Genichesk, where a landing party under Lieutenant Campbell Mackenzie set fire to storehouses and numerous ships in the harbour. A sudden change of wind direction would have reduced the amount of damage caused had not two officers, Lieutenants Cecil Buckley and Hugh Burgoyne, and Gunner John Roberts, returned ashore and started fresh fires where they would do most good, despite the presence of enemy troops and being beyond the gunfire support of their ships; all three were awarded the Victoria Cross.

Many Russian ships had fled from the Black Sea to the imagined security of the Azov as soon as the war had begun, and consequently the harbours of the latter were crowded. Just four days into his mission, Lyons was able to report that the enemy’s losses thus far amounted to four naval steamers, no less than 246 merchant vessels of various types, plus supplies of corn and flour sufficient to feed 100,000 men for twelve weeks.

At the beginning of June the light squadron, reinforced with twelve launches armed with 24-pounder howitzers and rockets, began operating in the Gulf of Taganrog. When, on 3 June, the governor of Taganrog itself declined to surrender, some of the town’s storehouses were set ablaze by fire from the boats. As this did not produce quite the desired result, Lieutenant Cecil Buckley and Boatswain Henry Cooper braved the fire of the 3500-strong Russian garrison to make repeated landings from a four-oared gig and start fresh blazes. By 15:00 the storehouses and most of the town were burning fiercely and the force withdrew. Boatswain Cooper received the Victoria Cross for his part in the action. On the 5th it was the turn of Mariupol and on the 6th Yeysk, all government stores in both places being destroyed. The situation now was that sea power was not simply disrupting the supplies of the Russian forces in the Crimea, but also those of the army fighting the Turks in the Caucasus as well. Having completed the first phase of its operations, the light squadron returned to Kerch where Lyons handed over to Commander Sherard Osborn. Sadly, on 17 June, Lyons received a mortal wound while taking part in a further bombardment of Sevastopol’s sea forts.

Having replenished, the light squadron returned to its work of destruction. On 27 June a landing party destroyed a convoy of wagons near Genichesk, which was also the scene of a lively action on 3 July. On the latter occasion the gunboat Beagle, commanded by Lieutenant William Hewitt, attacked the floating bridge connecting the town with the northern extremity of the Tongue of Arabat, which provided a major supply route into the Crimea. While the gunboat gave covering fire, Hewitt sent two boats to cut the bridge’s hawsers. With the Russians lining the beach only 80 yards distant, as well as shooting from nearby houses, this was a desperate business. Despite this, although the boats were riddled, only two men were wounded. The hawsers were cut under heavy fire by Seaman Joseph Trewavas, who received a minor wound while hacking at them. Trewavas was awarded the Victoria Cross. Simultaneously, the last remaining floating bridge between the Tongue of Arabat and the Crimea was burned by the paddle gunboat Curlew.

It was now apparent that the light squadron, and the new gunboats in particular, could go wherever they wanted and the Russians were powerless to stop them. Some extracts from Osborn’s despatches convey the daily nature of operations.

Delayed by the weather, we did not reach Berdyansk until July 15th. I hoisted a flag of truce in order, if possible, to get the women and children removed from the town; but, as we met with no reply, and the surf rendered landing extremely hazardous, I hauled it down and the squadron commenced to fire over the town at the forage and corn-stacks behind it; and I soon had the satisfaction of seeing a fire break out exactly where it was wanted. It became necessary to move into deeper water for the night; and, from our distant anchorage, the fires were seen burning throughout the night.

On the 16th the Allied squadron proceeded to Fort Petrovski, between Berdyansk and Mariupol. At 9.30 a.m., all arrangements having been made, the squadron took up their positions, the light-draught gunboats taking up stations east and west of the fort, and enfilading the works front and rear, whilst the heavier vessels formed a semicircle round the fort. The heavy nature of our ordnance soon not only forced the garrison to retire from the trenches, but also kept at a respectable distance the reserve force, consisting of three strong battalions of infantry and two squadrons of cavalry. We then commenced to fire with carcasses (i.e. incendiary shells) but, although partially successful, I was obliged to send the light boats of the squadron to complete the destruction of the fort and batteries, a duty I entrusted to Lieutenant Hubert Campion. Although the enemy, from an earthwork to the rear, opened a sharp fire on our men, Lieutenant Campion completed this service in the most able manner. Leaving the Swallow to check any attempt of the enemy to reoccupy the fort, the rest of the squadron proceeded to destroy great quantities of forage, and some of the most extensive fisheries, situated upon the White House Spit.

On July 17th, in consequence of information received of extensive depots of corn and forage existing at a town called Glafirovka upon the Asiatic coast, near Yeysk, I proceeded there with the squadron. The Vesuvius and Swallow were obliged to anchor some distance offshore. I therefore sent Commander Rowley Lambert (Curlew) with the gunboats Fancy, Grinder, Boxer, Cracker, Jasper, Wrangler and the boats of Vesuvius and Swallow. He found Glafirovka and its neighbourhood swarming with cavalry and therefore very properly confined his operations to destroying some very extensive corn and fish stores.

I next proceeded to the Crooked Spit in the Gulf of Azov (Taganrog) on the 18th; and I immediately ordered Commander Craufurd, in the Swallow, supported by the gunboats Grinder, Boxer and Cracker, and the boats of Vesuvius, Fancy and Curlew, to clear the spit and destroy the great fishing establishments situated upon it. While this service was being executed, I reconnoitred the mouth of the river Mius, 15.miles west of Taganrog, in HMS Jasper. The shallow nature of the coast would not allow us to approach within a mile and three-quarters of Fort Temenos. I returned to the same place, accompanied by the boats of HMS Vesuvius and Curlew, and HM gunboats Cracker, Boxer and Jasper. When we got to Fort Temenos and the usual Cossack picket had been driven off, I and Commander Lambert proceeded at once with the light boats up the river. When immediately under Fort Temenos, which stands upon a steep escarp of 80 feet, we found ourselves looked down upon by a large body of both horse and foot, lining the ditch and parapet of the work. Landing on the opposite bank, at good rifle-shot distance, one boat’s crew under Lieutenant Rowley was sent to destroy a collection of launches and a fishery, whilst a careful and steady fire of Minie rifles kept the Russians from advancing on us. We returned to the vessels, passing within pistol-shot of the Russian ambuscade.

On July 19th I reconnoitred Taganrog in the Jasper gunboat. A new battery was being constructed on the heights near the hospital, but, although two shots were thrown into it, it did not reply. To put a stop to all traffic and to harass the enemy in this neighbourhood, I ordered Commander Craufurd to remain in the Gulf with two gunboats.

A few days later the light squadron sustained its only serious loss of the campaign. The Jasper, commanded by Lieutenant Joseph Hudson, had silenced a Russian field battery. In an excess of enthusiasm, Hudson took the captured guns aboard as trophies, forgetting that the additional weight would result in the gunboat drawing more water. The ship ran aground and, although the guns were thrown over the side, she could not be got off. She was, therefore, abandoned and blown up – prematurely, some thought, in view of the small threat presented by the supine Russians. Despite this, during the weeks that followed, the light squadron continued to raid at will, to the point that repetition would become tedious. No sooner had the Russians brought forward fresh stores than they were destroyed long before they could reach the Crimea, either by gunfire or landing parties. In this way Genichesk, Beryansk, Taganrog, Mariupol, Arabat and other places on the Azov coast were all attacked regularly, in spite of strenuous Russian attempts to strengthen their defences.

Although the Russians were having much the worst of things in the Azov, their defence of Sevastopol was conducted with characteristic stubbornness. On 17-18 June Allied attempts to storm the Malakoff and the Redan, the garrison’s two principal defence works, were repulsed with heavy loss. Nevertheless, the cutting of the Crimean supply route began to affect both Sevastopol’s defenders and the Russian field army. On 16 August the latter made one last desperate attempt to dislodge the besiegers but were decisively defeated by the French and Sardinians on Traktir Ridge. As the fortress was now clearly doomed, the Russians began burning their remaining warships and made preparations to withdraw the garrison across the harbour. These were hastened when the French stormed the Malakoff on 8 September. That night the garrison withdrew after blowing up the rest of its fortifications, and the following morning the Allies occupied the city.

The fall of Sevastopol did not mean that the little ships’ work had ended. On the eastern side of the Kerch Straits the enemy had begun assembling a small army at Taman and Fanagorinsk and it was thought that when the winter ice closed the straits, this might be used to cross it and recapture Kerch. On 24 September an Allied force including the gunboats Lynx, Arrow and Snake, plus eight French gunboats, ferried nine infantry companies to Taman and provided covering fire while the troops disembarked. Taman was hastily abandoned, as was Fanogorinsk, where the fort and barracks were occupied and 62 guns rendered unserviceable. While this was taking place some 600 Cossacks appeared, only to be dispersed by the gunboats’ fire. The force then burned the buildings and retired to Kerch with a quantity of useful stores.

In the Sea of Azov the light squadron continued its depredations. On 4 November it was the turn of Glafirovka, the defences of which had been considerably strengthened since the last visit in July. Recruit, Grinder, Boxer and Cracker first engaged the enemy trenches with shrapnel while Clinker was towing in the boats of the landing party, then set the corn stores ablaze with carcasses. The fight ended with a charge by Marines and cutlass-wielding seamen, led by Lieutenants Day and Campion, which drove the Russians out of their positions. Simultaneously, other ships raided Yeysk so that the day’s operations left a two-mile stretch of coastline in flames. The last foray carried out by the gunboats and their landing parties penetrated the river Liman on 6 November, destroying stores piled along a four-mile frontage.

In the Caucasus, the Russians captured the Turkish fortress of Kars on 26 November, enabling the ministers of the new Tsar, Alexander II, to request peace negotiations with one success to their credit. The war had cost each side about a quarter of a million deaths, the majority caused by disease. Its results included the preservation of the Ottoman Empire’s integrity and the Tsar’s loss of his role as protector of the Sultan’s Orthodox Christian subjects.

It would be simplistic to suggest that the light squadron’s operations in the Sea of Azov were entirely responsible for the fall of Sevastopol. They did, however, make a considerable contribution to that end, and as far as resources and manpower were concerned, the light squadron was the most profit-bearing formation the Allies possessed. As Osborn commented in his despatch to his Commander-in-Chief:

I despair of being able to convey to you any idea of the extraordinary quantity of corn, rye, hay, wood and other supplies so necessary for the existence of the Russian armies, both in the Caucasus and the Crimea. During these proceedings we never had more than 200 men engaged.

Furthermore, at a trivial cost to itself, the squadron tied down tens of thousands of Russian troops across a wide area in an ineffective defence when they could have been more profitably employed elsewhere. In the subsequent honours and promotions Osborn became a Companion of the Bath and was promoted to captain; the rest of the squadron’s commanders also received promotion to captain, and the majority of its lieutenants became commanders. Eight Victoria Crosses were awarded during the Kerch/Sea of Azov operations. To our eyes, used to the strict application of the modern regulations governing the supreme award for valour, this may seem a surprisingly high number. It must, however, be remembered that at the time the newly instituted Victoria Cross was the only medal that could be awarded to officers and men of both British armed services for acts of exceptional gallantry; again, few would be so mean-spirited as to argue that the instances quoted above were unworthy of recognition.

The operations in the Sea of Azov also convinced the Royal Navy that, with the bulk of the Fleet retained in home waters for the defence of the United Kingdom, the so-called Crimean gunboats provided an ideal and inexpensive means of policing the often troubled waters of a global empire that was still expanding.