In the west, Imperial Germany launched the still debated Schlieffen Plan invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, a blueprint for a rapid victory on which all the hopes of the German general staff rested.

This encompassed a vast turning movement through Belgium that was to strike France in a “great right wheel” to concentrate all German forces in the west. This left the German east less well defended, in hopes of a quick victory against the western Allied armies that included a British Expeditionary Force that the Kaiser unwisely, but infamously, denigrated as “A contemptible army!”

The generals of this same staff had duly calculated upon East Prussia being invaded by the Russians, but they did not foresee at all the swiftness and massive strength with which it was done.

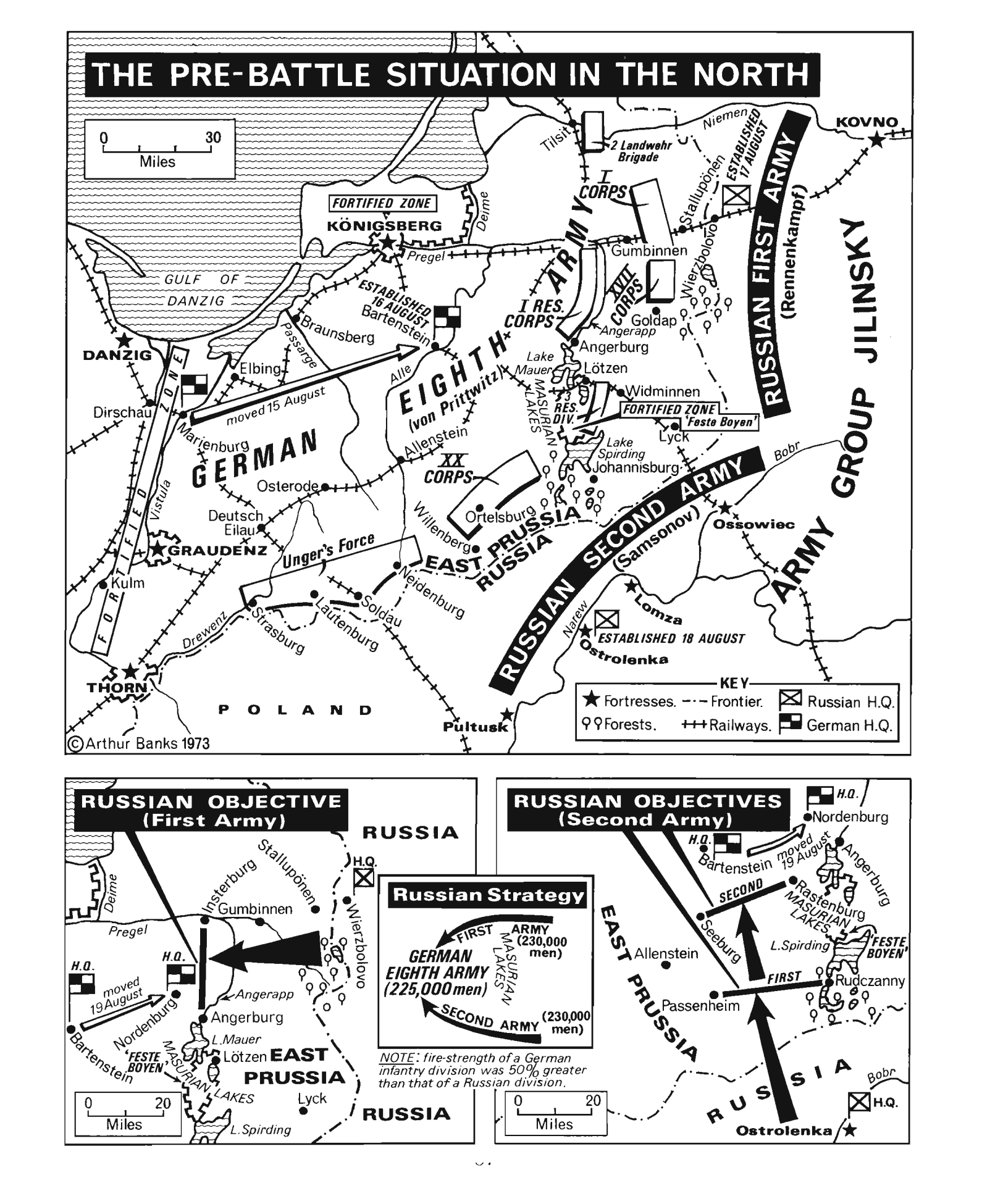

The German defensive forces in East Prussia that had already long been deployed to meet this expected Russian thrust was the 8th Army of fourteen divisions commanded by Gen. Maximilian von Prittwitz, who, as fate would have it, was a first cousin of von Hindenburg. Opposed to him were two full-sized and vaster Russian armies, both numerically stronger than his. Thus was East Prussia laid bare on August 15, 1914 to the advancing legions of the Tsar of All the Russias, the Kaiser’s own royal cousin, Nicholas II. Noted one military affairs commentator somewhat dramatically: “All Germany was bewailing the fire and sword that was sweeping East Prussia, and Wilhelm II’s pride was deeply stung.”

Although the Kaiser well knew that the Schlieffen Plan demanded utter concentration on the far more martially important Western Front, he nevertheless complained indignantly of the violation “Of our lovely Masurian Lakes!”

In the face of this great challenge, von Prittwitz hesitated in his immediate response, while his senior staff officer, Lt Col. Max Hoffmann, and two of his own corps commanders, Gens. August von Mackensen and Hermann von François, were champing at the bit to close with their eastern enemy in combat, but the nervous von Prittwitz held back.

On August 20, 1914, he telephoned von Moltke—with the suggestion of himself and his own staff chief—that, perhaps, the 8th Army should retreat en masse away from the oncoming Russian armies that might destroy his smaller command. This angered the Kaiser, and it put the count in a quandary as well. Both agreed that their two reluctant soldiers in the east would be replaced, but who by? That was the question.

Meanwhile, unknown to all of them, the Russian High Command had its own problems simultaneously.

Unquiet Allies! Gens. Rennenkampf and Samsonov

General of Cavalry Pavel (Paul) Karlovich Rennenkampf (April 17, 1854 to April 1, 1918)

Ever since Tannenberg, historians generally have seen him as that epic battle’s real loser and not the man blamed for it, Samsonov; the reason is that the former did not aid his colleague in need, thus allowing him to lose. Reportedly, the bad blood between them began during the earlier lost Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, when there occurred a similar incident following the Battle of Mukden. The slight rankled, unforgotten, almost a decade later.

Because he was a favorite of the Tsar, the errant Gen. Rennenkampf managed to survive both martial blunders, however, continuing to lead his army well into 1915 no less.

Having beaten von Mackensen at the Battle of Gumbinnen, stumbling badly during Tannenberg, and being beaten himself at the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes and at Łódź also—all in the summer of 1914—Rennenkampf was fired on October 6, 1915, over a year after the events.

Arrested and imprisoned after the February 1917 Revolution that overthrew his patron, the Tsar, Gen. Rennenkampf was charged with both embezzlement and mismanagement. His luck held again, however, and he was freed after the October 1917 Revolution that brought Lenin to office.

Then his luck ran out for good when he was executed on April 1, 1918 by the Reds for refusing to fight for the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War.

General of Cavalry Alexander Vasilyevich Samsonov (November 14, 1859 to August 30, 1914)

A veteran horse commander during both the Boxer Rebellion in China and then the Imperial Japanese Army in Manchuria afterwards, Gen. Samsonov suffered the greatest defeat of any C.O. of any armed force of the Great War right at its very outset.

By August 29, 1914, his Russian 2nd Army was surrounded by the Germans in a forest situated between Allenstein and Willenberg in East Prussia, and the next day, he shot himself near the latter, his body—pistol in hand and bullet in head—being found later by a German patrol.

The International Red Cross arranged for his body to be returned to his widow in 1916.

General of Infantry Hermann von François, Disobeyer of Orders

Gen. Hermann Karl Bruno von François (January 31, 1856 to May 15, 1933) stands out in the early history of the Great War as the premiere disobeyer of orders of several superior commanders running. As such, he was staying true to one of the cardinal rules of all German officers: use your initiative at all times. This he did, in the very first triad of major battles on the Eastern Front: Stallupönen, Gumbinnen, and the all-important Tannenberg/Christmas Mountain.

Born in Luxembourg a Huguenot, von François began the war as commanding officer of the German 8th Army’s 1st Corps, tasked with defending the East Prussian frontier against any Russian Army invasion headed for the provincial capital of Königsberg, site in 1861 of the coronation of King Wilhelm I of Prussia, the last such ever held anywhere.

On August 15, 1914, East Prussia was suddenly and surprisingly invaded by the right wing of a double-pronged thrust of Russian Gen. Pavel Rennenkampf’s 1st Army. As von François dealt with this, his 8th Army commander, Gen. von Prittwitz, two days later ordered him to retreat in front of the Russian advance.

Col. Gen. Maximilian von Prittwitz und Gaffron: First Fired!

Maximilian Wilhelm Gustav von Prittwitz und Gaffron (November 27, 1848 to March 29, 1917) has the distinction of being the very first commanding general of any army on either side of the Great War to be fired from his post; in this case, for being willing to abandon East Prussia to the invading Russian Army via a speedy retreat west of the Vistula River. Neither the Kaiser nor von Moltke accepted this, so von Prittwitz was replaced by the later-styled von Hindenburg, then Beneckendorff.

Prittwitz, like his cousin, had also fought in both the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, and, unlike the then-retired von Hindenburg, in 1913 was both promoted full general at four stars as well as CO of the 16th Army Corps at Metz, opposite the French Army.

He commanded the German 8th Army defending East Prussia a mere three weeks to the day—August 2–23, 1914—but allowed himself to be spooked by the rapid invasion of his charge by a pair of Russian armies under veteran generals on August 15, 1914.

Alarmed by the near defeat at Stallupönen and the actual rout of von Mackensen at Gumbinnen, von Prittwitz decided on a complete withdrawal but was stopped in his tracks by the Kaiser and his CGS.

The cast-down commander lived in retirement at Berlin in the vast, dark, cold shadow of Tannenberg, dying of a heart attack at the age of sixty-nine, nicknamed “Fatty” by his detractors. His martial reputation has not yet recovered.

German 8th Army East Prussian Headquarters: Castle Marienburg at Malbork

Gen. von Prittwitz’s former military headquarters in East Prussia was in the famous Malbork red brick Castle Marienburg, built in the thirteenth century by the Knights of the Teutonic Order as their command center in what later evolved into Royal Prussia, completely abolished by the Allies in 1945.

Known as Marienburg in German when founded in 1274, the town was named for the order’s patron saint, the Virgin Mary, and remains today Europe’s largest Gothic-style fortress. The town and the fort were destroyed by the Red Army on March 9, 1945, and that June became part of today’s Poland as Malbork.

Von François Wins the Battle of Stallupönen, August 17, 1914

Overall, the Russians fielded ten full armies versus the Germans’ lesser eight for their projected march on Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia, which they duly invaded in force on August 15, 1914.

Stallupönen (today’s Nesterov in Russia) was the very first conflict fought by the armies of Imperial Germany and Tsarist Russia on the newly opened Eastern Front on August 17, 1914, just two days later.

Von François pluckily and successfully waged an attack with his German 1st Corps against four full Russian infantry divisions, even creating a gap between two of them in what proved to be a minor victory, but one that made no dent in the enemy’s advance afterwards. Ordered by his superior, von Prittwitz, to break off this fight, François told his adjutant to reply thus: “Report to Gen. Prittwitz that Gen. von François will withdraw when he has defeated the Russians!”

True to his boast, the plucky François then withdrew 15 miles westward, and three days later, he engaged Rennenkampf again at the Battle of Gumbinnen that was a rout for German Hussar Gen. August von Mackensen—his first and only.

The Battle of Gumbinnen, August 17–23, 1914

Gen. von Prittwitz—emboldened by von François’s pluck at Stallupönen—attacked too soon at Gumbinnen, however, causing it to instead become a Russian victory, their first over the hated and arrogant German Army at what is now Gusev, Russia. Samsonov’s Russians defeated Mackensen’s Germans, despite the fact that the victors suffered 18,839 losses in all to the “beaten” foe’s 14,607 according to 2016 statistics. The German 8th Army numbered 148,000 men versus their enemy’s superior force of 192,000 soldiers.

Still fuming that von François had disobeyed his orders in engaging the Russians at Stallupönen just days before, now von Prittwitz disobeyed his own orders from Moltke not to give battle until the campaign in the west was won. He rashly decided to follow up his subordinate’s successful fight with one of his own at Gumbinnen, where Russian cavalry encountered German infantry on August 19, 2014.

This time, von François was given an order to advance against the Russians that night, his cavalry backing up the German infantry, but the resulting battle stalemated when the Russians ran out of artillery ammunition. Until that happened, though, their gunfire halted Mackensen’s advance against Rennenkampf and led to the German’s flank being turned, thus precipitating a rout to their own lines at Insterburg–Angerburg to the rear, with 6,000 POWs being bagged by the victorious Russians.

According to Brownell in First Nazi: “The uncharacteristic sight of defeated German soldiers streaming moblike to the rear really unnerved von Prittwitz,” who feared that his own army would be completely sandwiched, and thus destroyed between those of Rennenkampf and Samsonov: “Prittwitz panicked and—with a decision out of all proportion to the severity of the situation—ordered a general retreat to the Vistula River, leaving East Prussia to the Russians.”

Back at KHQ Koblenz, both His Majesty and von Moltke had visions of Russian Cossack horses trotting down the boulevards of Berlin itself, as had occurred during the Seven Years’ War that Frederick the Great almost lost to the Russian Army. Their solution had been to send the duo east, but they also wrongly detached a trio of infantry corps plus a cavalry division from the marching wing of the German Army in the west to march eastward, where they arrived too late to have any effect whatever on the Battle of Tannenberg, thus being useless on fronts both east and west simultaneously.

Despite his surprise victory against both Mackensen and von François, Gumbinnen caused Gen. Rennenkampf himself to pause and take stock of the aggressive German commanders to his front. By then, von Moltke had replaced the retreating von Prittwitz, and von François was on his way via rail to take on yet another Russian force. This was the 2nd Army of Gen. Samsonov, and, despite his disobedience at Gumbinnen, the new commander Beneckendorff entrusted the scrappy von François with the decisive aspect of the approaching Battle of Tannenberg as well.

How Tannenberg Evolved from the German Defeat at Gumbinnen

By now, the duo had reached their new command and jelled with the savvy Hoffmann as well. Meanwhile, a note had been found on the body of a dead Russian officer that changed the entire strategic picture overall.

Recalled Hindenburg in his postwar memoirs: “It told us that Rennenkampf’s army was to pass the Masurian Lakes on the north, and advance against the Insterburg–Angerburg line … to attack the German forces presumed to be behind the Angerapp, while Samsonov’s Narew Army was to cross the Lötzen–Ortelsburg line to take the Germans in flank.”

Thus forewarned, the duo stopped the German retreat, reversed course, and decided to attack instead their Russian foes, thus setting the stage for the Battle of Tannenberg, acknowledged by all martial historians as “One of Germany’s greatest victories.”

This saw von François as the spear point of the attack against Samsonov on August 27, 1914, plunging deep into the penetrated Russian rear. This led the new Chief of Staff Ludendorff to fear a counterattack from Rennenkampf to aid Gen. Samsonov, so von François was ordered to halt his advance. This the latter again refused to do, thus breaking orders for the second important time within days, continuing his own encirclement of a much larger force, that of Samsonov.

The new commander and his chief of staff got the majority glory for the victory, but they never forgot who had really earned it: Hermann von François.

| Hermann von François |

|---|

When Hindenburg and Ludendorff went south to lead the 9th Army in Russian Poland, François remained with his corps in East Prussia and led it with much success in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes the following month. When General Richard von Schubert, the new commander of the 8th Army, ordered him to retreat, he dispatched a telegram to the OHL describing his success and stating “the Commander is badly counselled.” The telegram impressed the Kaiser so much that he immediately relieved Schubert and, on 3 October, gave von François the command of the 8th Army. He did not hold it for long. When Hindenburg and Ludendorff prepared their counter-attack from Thorn in the direction of Łódź, François was reluctant to send the requested I Corps, sending the badly trained and ill-equipped XXV Reserve Corps instead. That was too much for his superiors. In early November 1914 von François was removed and replaced by General Otto von Below.

After some time spent “on the shelf”, François received the command of the XXXXI Reserve Corps on 24 December 1914, and after a spell in the West, he returned to the Eastern Front in April 1915 where he took part in the Spring Offensive that conquered Russian Poland. He continued to distinguish himself. He won the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military decoration, on 14 May 1915 for his performance in the breakthrough at Gorlice, and had the Oak Leaves attached to it in July 1917, for outstanding performance during the Battle of Verdun. In July 1915 he was transferred back to the Western Front to take command of the Westphalian VII Corps in France, and in July 1916 Meuse Group West in the Verdun sector. However he never received any further promotion or serious commands under Ludendorff, and gave up his command in July 1918 and was placed on the standby list until October 1918 when he retired.