The Albatros Flugzeugwerke produced their first aircraft in 1912, the Albatros L.3, a single-seat scout type. This was followed by the L.9, a single-seat scout type designed by Claude Dornier, who later was to join the Zeppelin Company as their chief designer.

The Albatros company, co-founded and owned by Dr Walter Huth, had been in existence since 1909 and was founded with a capital of 25,000 marks. It was situated, together with other aircraft manufacturers, at the airfield at Johannisthal, near Berlin. As the Prussian Army became more and more interested in aviation, the manufacturers came up with a variety of offers in an attempt to secure contracts from them. On 2 October 1909, Dr Huth approached the War Ministry and offered to buy a French Latham aircraft for the military and supply an instructor to train military pilots, if they would pay for any repairs and maintenance costs. The offer was declined as the Wright Company had offered a similar package – for free. This prompted the Chief of the General Staff, General von Moltke, to put forward a recommendation that the War Minister sanction the training of suitable officers as pilots. At the end of 1909, von Moltke had been well aware that the French were already buying numbers of aircraft in addition to building some of their own, and were training military pilots.

The General Inspectorate of Military Transportation tried to maintain an impartial stance towards the various aircraft manufacturers, or so it was thought. For some unknown reason, they seemed to favour the Albatros Company, but this came to a head in 1911 when Otto Weiner, one of the directors of Albatros, urged Colonel Messing of the Inspectorate not to deal with the Luftverkehrsgesellschaft (LVG), claiming that the company was just a sale agent for Albatros. The LVG Company was owned by Arthur Mueller, and he allegedly persuaded Otto Weiner that the Army would rather deal with him than Albatros. Albatros claimed, however, that they reserved the right to sell directly to the Army and LVG would receive 750 marks for each aircraft sold. The fact that the LVG Company had saved the Albatros Company from collapse in the spring of 1911, after it had had a request for a subsidy from the Army rejected, seems to have been forgotten by Otto Weiner. LVG had purchased four aircraft from Albatros at a cost of 100,000 marks, which enabled the company to continue production.

The War Ministry supported LVG’s complaint of unfair dealing, and ensured that all transactions concerning the contracts issued for the purchase of aircraft from the various companies was done on the basis of ability to provide.

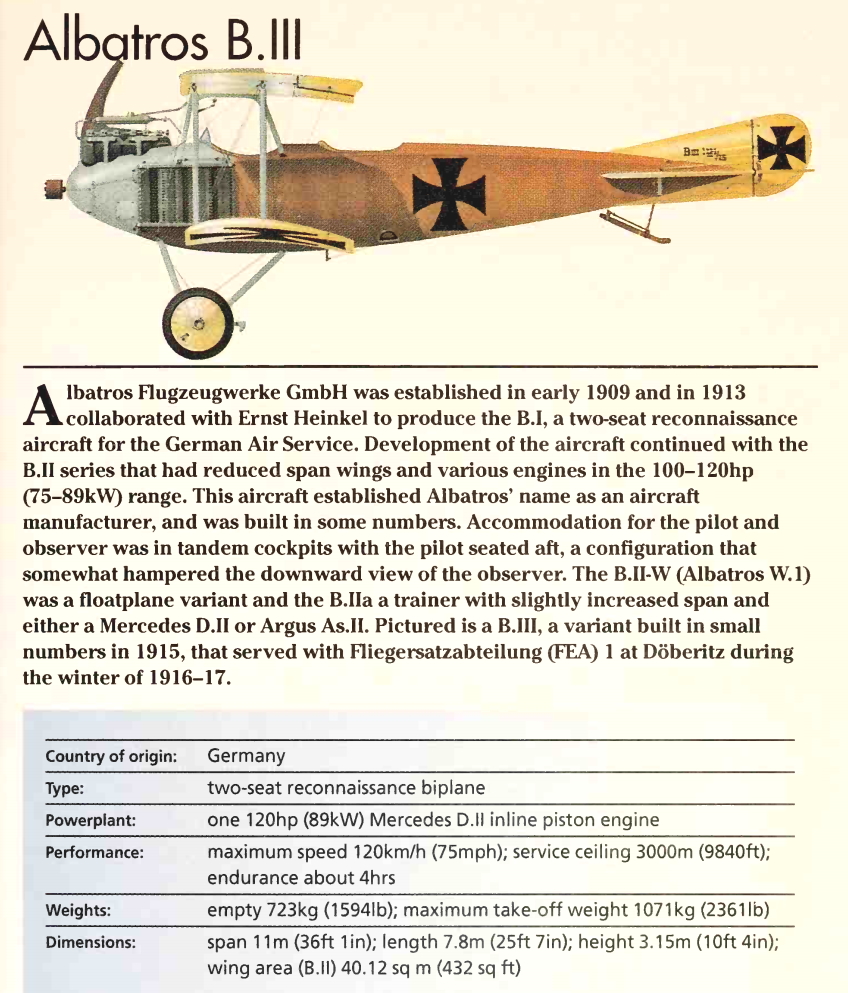

The first of the Albatros reconnaissance/trainers, the B.I, appeared in 1913. The aircraft was initially used as a trainer, but with the outbreak of war it was used both as a trainer and reconnaissance aircraft. Powered by a 100-hp Mercedes D.II engine, the B.I had a top speed of 65 mph and an endurance of 4 hours. Only a small number were built before being replaced by the B.II. The B.II, like the B.I, had an extremely strong, slab-sided fuselage made up of four spruce longerons covered with plywood. As in all the early aircraft, the pilot sat in the rear cockpit, which gave him a very limited view for take-off and landing. Used for training and reconnaissance duties, the B.II was replaced by the B.III with only minor modifications.

The arrival of Allied fighter aircraft prompted the development of a faster reconnaissance aircraft. Albatros produced the (OAW – Ostdeutsche Albatroswerke) C.I, powered by the 150-hp Benz engine, but only two were built. A second Albatros, the (OAW) C.II built in 1916, powered by a straight eight Mercedes D.IV engine was produced. This time only one was built.

Early in 1915, the company embarked on a singularly ambitious project, a four-engined bomber. Designed by Konstr. Grohmann, the Albatros G.I, as it was known, had a wingspan of 89 ft 6½ in (27 metres), a wing area of 1,485 sq ft (138 sq metres) and a fuselage length of 39 ft 4¼ in (12 metres). It was a very large aircraft. On the lower wing, four 120-hp Mercedes D.II engines in nacelles were mounted, driving four tractor propellers. The first flight took place on 31 January 1916, and was flown by a Swiss pilot, Alexander Hipleh. The G.I became the forerunner of the G.II and G.III, although the two latter aircraft were twin-engined bombers.

A completely different design early in 1916 produced the Albatros C.II. Called the Gitterschwanz (Trellis-tail), the design was of the pusher type, looking very similar to the De Havilland DH 2. Powered by a 150-hp Benz Bz III engine, the C.II did not measure up to expectations and only one was built. This was quickly followed by the Albatros C.IV, which reverted back to the original basic design. A 160-hp Mercedes D.III engine was fitted into the C.III fuselage, to which a C.II tail assembly and undercarriage were fixed. Again, only one of these aircraft was made.

A purely experimental model, the Albatros C.V Experimental, was built at the beginning of 1916. This had a wingspan of 41 ft 11½ in, supported by I-struts in an effort to test the inter-plane bracing. Powered by an eight-cylinder 220-hp Mercedes D.IV engine, the C.V Experimental supplied a great deal of information to Albatroswerke. The C.VI followed soon afterwards, and was based on the C.III airframe and powered by a 180-hp Argus As III engine, giving the aircraft a top speed of 90 mph and enabling it to carry enough fuel for a 4½-hour flight duration. In 1917, a night bomber version, the C.VIII N, evolved. Bombs were carried beneath the lower wings, but it was only powered by a 160-hp Mercedes D.III engine. Only one was constructed.

At the same time as the night bomber was being built, a two-seat fighter/reconnaissance aircraft, the Albatros C.IX, was being made. With a straight lower wing and a considerably swept upper wing it presented an unusual aircraft, but only three were built. This was followed by one version of the Albatros C.XIII, and again it was for experimental purposes. A return to the original design of the two-seater reconnaissance produced the Albatros C.XIV. There was one difference: the C.XIV had staggered wings, and again only one was built. The C.XIV was later modified into the C.XV. It was too late for the development of this aircraft in any numbers, as the end of the war came.

The air supremacy of the Imperial German Air Service during 1916 had been gradually eroded by the rapid development of the Allied fighter aircraft. In a desperate attempt to gain control again, the Albatros Werkes was approached to design and build a fighter that would do just that. Looking at the highly manoeuvrable Nieuport that was causing some of the problems, the company’s top designer Robert Thelen set to work and produced a design that combined speed and firepower. If his aircraft couldn’t outmanoeuvre the Nieuport, the Albatros could catch it and blast it out of the sky.

A 160-hp Mercedes engine or the 150-hp Benz, which was enclosed in a semi-monocoque plywood fuselage, powered the first of the Albatros series, the D.I. The cylinder heads and valve gear were left exposed, as this gave assisted cooling and greater ease of access for the engineers who had to work on the engine. Engine cooling was achieved by mounting two Windoff radiators, one on each side of the fuselage and between the wings, and a slim water tank mounted above and toward the rear of the engine, at an offset angle slightly to port. The extra power given to the aircraft enabled the firepower, twin, fixed Spandau machine guns, to be increased without loss of performance.

The fuselage consisted of three-eighths thick plywood formers and six spruce longerons. Screwed to this frame were plywood panels, and the engine was installed with easily removable metal panels for both protection and ease of maintenance. The wings, upper and lower, and the tail surfaces were covered with fabric. The fixed tail surfaces and upper and lower fins were made of plywood. The control surfaces were fabric covered over a welded steel-tube frame with a small triangular balance portion incorporated in the rudder and the one-piece elevator.

The undercarriage, a conventional, streamlined steel-tube V-type chassis, was fixed to the fuselage by means of sockets, and sprung through the wheels with rubber shock cord.

The Albatros was a very satisfactory aircraft to fly, but it was discovered to have a major drawback during combat. The top wing, because of its position to the fuselage, obscured the pilot’s forward field of vision. The problem was solved by cutting out a semi-circular section of the top wing in front of the pilot, and by lowering the wing so that the pilot could see over the top.

The first Jasta to receive the Albatros D.I, on 17 September 1916, was Jasta 2, which was commanded by the legendary Oswald Boelcke. Three weeks later Boelcke was killed when his Albatros was in involved in a mid-air collision with his wingman Erwin Böhme as they both dived into attack the same British aircraft, a DH.2 of No. 24 Squadron RFC.

In the middle of 1916, the German Naval High Command decided that it would be a good idea to have a single-seat fighter floatplane as a defence aircraft. The Albatros D.I was used as the basis of the Albatros W.4, although the latter was considerably larger in overall dimensions. The wingspan was increased by 1 metre.

Late in 1916, the Albatros D.III appeared with subtle, but noticeable changes to previous models. However, by the summer of 1917, this too had been superseded by the Albatros D.V and D.Va, just as the S.E.5s and SPADs (Société Pour Aviation et ses Dériéves) of the Allies started to regain control of the skies. The same problem seemed to dog the Albatros throughout its lifetime: the lower wing had a tendency to break up in a prolonged dive. In one incident, Sergeant Festnter of Jasta 11 carried out a test flight in an Albatros D.III, when at 13,000 feet the port lower wing broke up, and it was only his experience and a great deal of luck that prevented the aircraft crashing into the ground. Even the legendary Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen experienced a similar incident on 24 January 1917, while testing one of the new Albatros D.IIIs that had recently arrived at Jasta 11.

Tests were carried out, and it was discovered that the single spar was positioned too far aft, causing vibration which increased as the dive continued. This eventually resulted in the structure of the wing collapsing under the erratic movement. A temporary stopgap was achieved by fitting a short strut from the V interplane to the leading edge. Instructions were then given to pilots not to carry out long dives in the Albatros, which, as one can imagine, drastically reduced the faith pilots had in the aircraft, especially when under combat conditions.

A large number of the Jagdstaffels (fighter sections) were being supplied with the Albatros III and IV, and once again superiority in the air passed to the Germans. Those pilots rapidly becoming famous as ‘Aces’ were flying the Albatros IIIs and IVs, among them Werner Voss and Prinz Friedrich Carl of Prussia. The latter, who commanded a Flieger-Abteilung unit, kept an Albatros IV with Jasta 2 for his personal use. The superiority of the Albatros IIIs and IVs, however, was short-lived, with the arrival of the Sopwith Triplane and the SPAD S.VII, and later the S.E.5 and Sopwith Camel. The Germans quickly realised that every time they came up with a superior design, the Allies countered it with an even better one. The Allies also had the advantage of being able to turn to a variety of aircraft manufacturers, whereas the Germans were limited in their choice.

The Albatros Werke were pressurised into improving the Albatros, with the result that the Albatros D.V was developed. The D.V had a major change to the shape of the fuselage. The D.III fuselage, with its flat sides, was replaced with an elliptical fuselage. The aileron cables were routed through the top wing instead of the lower wing, but the wing structures were the same. Fitted with a 200-hp Mercedes D.IIIa six-cylinder, in-line water-cooled engine, the increased speed of the D.V started to redress some of the balance of air power, but was not sufficient to make any substantial difference. Even the appearance of the D.Va, although it was a superior aircraft to the D.V, did nothing to improve the German air superiority.

The company was not being idle: the Albatros was being developed, and an experimental model, the D.IV, produced. With the fuselage of a D.Va and the wings of a D.II, the experimental fighter was powered by a specially geared version of the 160-hp Mercedes D.III engine, which allowed the engine to be completely enclosed in the nose. There were a number of insurmountable problems with the engine and the project was scrapped. Two months later, in August 1917, another experimental fighter appeared, the D.VII. It was powered by a V8 195-hp Benz Bz IIIb engine, which gave the aircraft a top speed of 127 mph and a climb rate of almost 1,000 feet per minute. Again only one model was built.

The appearance of the Albatros Dr.I in 1917 was to assess the possibilities of producing a triplane. After many tests, the aircraft was deemed to be no better than the D.V and was not continued. Then at the beginning of 1918 another triplane appeared, the Albatros Dr.II. The heavily staggered triple wings were braced with very wide struts, and ailerons were fitted to all the wingtips. Powered by a V8 195-hp Benz IVb engine with frontal-type radiators that were mounted in the centre section between the upper and middle wings, the speed of the aircraft was affected considerably because of the drag caused by the position of the radiators.

A two-seater reconnaissance/bomber appeared at the beginning of 1918, the Albatros J.II. Powered by a 220-hp Benz IVa engine, which gave the aircraft a top speed of 87 mph, the J.II was armed with twin fixed, downward-firing Spandau machine guns and One manually operated Parabellum machine gun in the rear cockpit. The downward-firing guns protruded through the floor of the fuselage, between the legs of the undercarriage. Four examples were built, but it arrived after the Junkers J.I, and the success of the J.I overshadowed the J.II to the extent that no more were built.

A number of prototypes made their appearance early in 1918, the first being the Albatros D.IX. It was powered by a 180-hp Mercedes D.IIIa engine, giving it a top speed of 96 mph. Only one was built. A second model appeared, the Albatros D.X, powered by a V8 195-hp Benz IIIb engine. This gave the aircraft a top speed of 106 mph. At a fighter competition at Aldershof it initially outperformed all the other competitors, but was unable to sustain the performance throughout. Again, only one model was built. The Albatros D.XI that followed was the first Albatros aircraft to use a rotary engine. Fitted with the Siemens-Halske Sh III of 160-hp, it was installed in a horseshoe-shaped cowling with extensions pointing toward the rear. These extensions assisted in the cooling by sucking air through the cowling. Two prototypes were built; one with a four-bladed propeller, the other was a twin-bladed model.

Two prototype Albatros D.XIIs followed, both fitted with different engines, but fitted with a Bohme undercarriage, which for the first time featured compressed-air shock absorbers. Neither aircraft was considered for production.

The Albatros D.V model was the most famous of all the Albatros aircraft, and was assigned to various Jastas in May 1917. In an attempt to bolster flagging morale, pilots were encouraged to emblazon their aircraft in ways that would personalise them. Baron Manfred von Richthofen had his Albatros D.V 1177/17 painted all red, as was his later version No. 4693/17, hence the name given to him by the Allies, ‘The Red Baron’. Eduard Ritter von Schleich had his Albatros D.V painted all black and became known as the ‘Black Knight’. By May 1918 there were 131 Albatros D.Vs and 928 D.Vas in operational service, but by now it was too late, the war was over.

One other aircraft appeared in 1917 and that was the Albatros G.I. Built by the Ostdeutsche Alabatroswerke GmbH, they had been contracted to build three bombers for the Staaken company. Otto Weiner and Dr Walter Huth had created Ostdeutsche Alabatroswerke GmbH in Schneidemühl on 23 April 1914. The latter had been one of the founders of Albatros Flugzeugwerke GmbH when it had been in Johannisthal. Although bearing the name of Albatros, the company was initially independent, that is until 1917, when it was taken over by the Albatros Flugzeugwerke GmbH.

The Albatros G.I led to the development of the G.II and G.III, and it was this that persuaded the authorities to award the three Staaken aircraft contract to the Albatros Company.