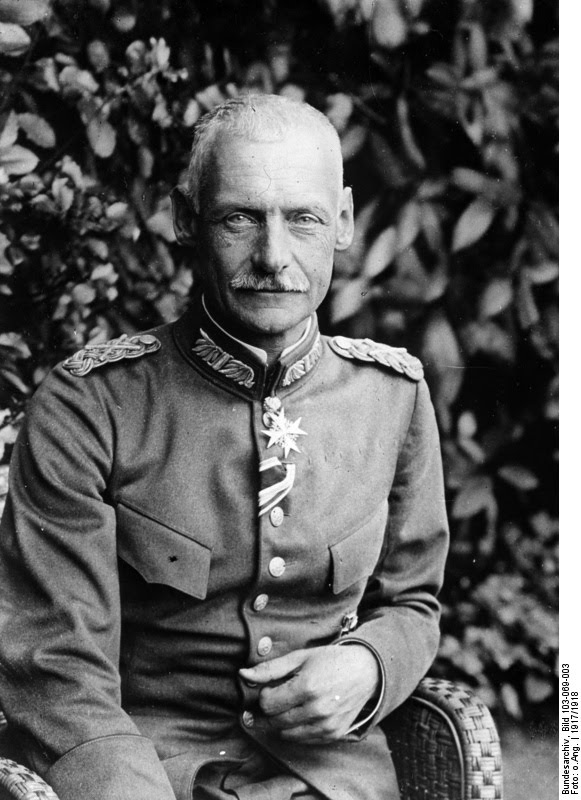

“In his hand, the marshal’s staff was more than just an ornament!” it was said of Bavaria’s heir to the throne, Crown Prince Rupprecht, who both served a Kaiser and frightened a future Nazi Führer.

The noted German author Blohm referred to Rupprecht as “A man of simple tastes who was a great soldier and a powerful leader.” Even his testy battlefield superior and later critic Ludendorff said of Rupprecht that “He is a man who takes his rank and his military task very seriously. With the help of his General Staff, he was able to master its demands the way a great leader should.”

Bongard described Rupprecht as “A man of imposing features and presence … without doubt the ablest and most professional of the three German Princely army group commanders…”

Nor was Rupprecht afraid to speak his mind in the highest circles of government, and also at general headquarters, as when, in 1917, he warned, “Return Poland to Russia, or we will lose the war!”

Indeed, even by the autumn of 1916, he was advocating “A peace without victory” and “The renunciation of all conquests, to gain a peace of understanding,” thus revealing a bent for statesmanship even after he had achieved his own craft’s highest award.

This was his marshal’s baton from the hands of the man whom even the Kaiser referred to as “the field marshal,” Paul von Hindenburg, on July 23, 1916. Rupprecht’s promotion became official the following August 1, 1916, the same date that his royal uncle, Prince Leopold of Bavaria, received his marshal’s baton also. More to the cutting point, the German crown prince was never awarded a like staff.

Both Rupprecht and his august uncle hailed from the twelfth-century South German ruling House of Wittelsbach dynasty, whose first monarch had been King Otto I. But for the loss of World War I by Germany, most likely Crown Prince Rupprecht would have succeeded to the very same throne as well, but it was not to be.

The crown prince was a great grandson of King Ludwig I, who had abdicated in 1848 during that year’s liberal revolution and had been succeeded by his son, Maximilian II, who died in 1864, when his unstable son, aged eighteen, ascended the Bavarian throne as King Ludwig II.

When the latter drowned under mysterious circumstances at the Starnberg Lake on June 13, 1886, Ludwig I’s second son, Luitpold, took over (Ludwig’s younger brother, Otto, had long been mentally ill), becoming King Ludwig III on November 5, 1913, reigning until the 1918 Revolution. His son was thus the Crown Prince Rupprecht of our saga.

The latter was born on May 18, 1869, the son of an Austrian princess as well. On August 8, 1886, after being both privately tutored and graduating from grammar school, Rupprecht was appointed a second lieutenant with the Infantry Lifeguard Regiment, and he would eventually serve in all three branches of the military services of the day, including cavalry and artillery as well.

In 1889—the year of Cpl. A. Hitler’s birth in neighboring Austria—Rupprecht began his university studies in both Munich (his familial capital) and the Imperial City of Berlin at rival Prussia and returned to later serious military studies. These included strategy at the general staff level, the leadership of troops in battle, and combat tactics, working his way up in rank until in 1906 he was named general of infantry and 1st Army commander (aged thirty-five).

Besides all thing martial, Rupprecht’s hobbies were art and travel, visiting Savoyard Italy, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, England, Sweden, India, Ceylon, Java, China, and Japan, authoring a trio of published books on his trips in 1906, 1922, and 1923. His military memoirs—also in three volumes—were published in 1929 as My Wartime Diary.

He was married twice, first to Princess Marie Gabrielle, also from the House of Wittelsbach, but she died after only eleven years of marriage. The crown prince remarried in 1917 to Princess Antonia, daughter of Grand Duke Wilhelm of Luxembourg, a state occupied by the German Army at the very start of the Great War in August 1914.

By then, Rupprecht was already a colonel general, and he was asked to lead the 6th Army, with his first chief of staff being Maj. Gen. Krafft von Dellmensingen, who was then the Bavarian Army chief of staff also. The two men commanded 200,000 soldiers.

In 1914, each German Army corps comprised two infantry divisions apiece of 17,500 officers and enlisted men, plus 4,000 horses, seventy-two guns, and twenty-four machine guns. Corps troops included heavy artillery and field hospitals, as well as bakeries, bridging trains, and supporting logistical support columns.

The Reserve Corps did not have heavy artillery, while a reserve division possessed but half the number of normal infantry field guns. A cavalry corps comprised two or three horse divisions, each with 5,200 officers and troopers, 5,600 mounts, motor transport, twelve guns, six machine guns, and field radio units.

The overall Imperial German Army in 1914 boasted 2 million soldiers in eight army commands, plus reserve forces, raising the figure to 3.8 million men. On its southern flank—invading both Belgium and Luxembourg—were the 6th and 7th Armies under Crown Prince Rupprecht, tasked with holding the enemy on their line.

Of their commander, Tuchman asserted that he was “Erect and good looking in a sensible way.… He came from a less eccentric branch of his family … and was descended from the Prince Rupert [of the Palatinate] who had fought for King Charles I of England against Cromwell” in the English Civil War.

“In memory of King Charles, white roses decorated the Palace of Bavaria every year on the anniversary of the Regicide,” but the Bavarian Army was considered to be thoroughly German.

“They were barbarians!” asserted French Gen. Auguste Dubail (1851–1934) after the first days of 1914 combat, having sacked their billeting houses, ripping up chairs and beds, ransacking closets, tearing down curtains, and smashing already trampled furniture in their wake, looting as well both ornaments and utensils. “These—as yet—were only the habits of troops sullenly retiring—Lorraine was to see worse!”

Rupprecht’s initial orders to stay put—protecting the Reich and the German speaking Czech Sudetenland from a possible French invasion—irked the Bavarian crown prince, who was champing at the bit to assault the French. He had little patience with the apparent timidity of general H.Q., which was mainly concerned about the proper execution of the Schlieffen Plan.

Noted Asprey in The German High Command: “After several skirmishes, the 6th Army was ordered to withdraw on 15 August 1914 from the impending French attack. The French actually came out of their fortifications, but only slowly followed the withdrawing Germans”—a retreat that Rupprecht felt would demoralize his men if allowed to continue.

“Either let me attack or issue definite orders!” he yelled into a staff telephone. He got his wish, and on August 20–21, 1914, his 6th Army and the 7th then under former German War Minister Gen. Josiah von Heeringen defeated the French with a surprise assault in that very same Lorraine as above.

The battle raged across a front 80 kilometers wide. By evening, the French 2nd Army was overrun, and Moltke agreed to let Rupprecht continue his attack to Nancy, forcing part of the French forces back across their border thereby.

The crown prince had won his point with general H.Q. by telling his superiors: “The French have had huge losses in fruitless attacks on our defensive positions at Sarrebourg and Morhange: an absolute massacre! We must exploit this success! I agree that it is a good thing to pin down the French right wing, but it would be even better to destroy it!”

Still, despite Rupprecht’s battle lust, the French under both Gen. Dubail and Gen. Noel de Castelnau (1851–1944) brought the plucky Bavarian’s assault to a standstill. Still later, his armies—along with all the other German ground forces—would be stalled again in the overall drive on Paris after First Marne.

As a result, Crown Prince Rupprecht moved his headquarters to St Quentin, during which heavy fighting again took place, this time with the British. The Race to the Sea Battle of Arras occurred during October 1–13, 1914, followed by the Battle of Lille-Ostend, until the enemy flooding of a canal again halted the forces of Rupprecht.

More severe fighting occurred over several months until a stable new German front could be established and held.

During the year 1915, another Battle of Arras took place, as well as the Battle of the Loretto Heights, during which an enemy breakthrough was halted by the German defenders, with heavy losses on both sides.

During the Verdun mauling, the Bavarian heir to the throne stood opposite the BEF. Rupprecht’s then chief of staff, Gen. Hermann von Kuhl, was summoned to Berlin to appear before Gen. von Falkenhayn,

Informed of a coming enemy offensive, Kuhl was duly warned of an “impromptu British riposte north of Arras,” after which a counterattack of eight German divisions would occur in mid-February 1916. Von Kuhl refuted this assertion as nonsense, noting the alleged complete unpreparedness of the new “Kitchener Armies.” Falkenhayn repeated this again to Kuhl on February 11, 1916, adding that he hoped the expected British assaults “Would bring movement into the war once again.”

When he heard this, a miffed Crown Prince Rupprecht scoffed: “Gen. Falkenhayn was himself not clear as to what he really wanted, waiting for a stroke of luck that would lead to a favorable solution” on the stagnant, stalemated Western Front.

Rupprecht correctly assessed that the infamous Battle of Verdun would become a bloody maw for both sides, and hardly the decisive victory for them that the embattled Wilhelmine Second Reich and its author sought.

Using his good graces at the imperial court at Berlin with the Kaiser, Crown Prince Rupprecht helped in the general overthrow of the Kaiser’s favorite von Falkenhayn. Thus came the eastern duo to the fore, and with Ludendorff postwar, Rupprecht won a later celebrated libel suit in court.

Of his commands, Bongard notes that he “Remained with the 6th Army in Lorraine during the” (September–November 1914) “Race to the Sea” and for most of the two ensuing years of war; was appointed commander of the northern army group comprising the 2nd, 4th, 6th, and 17th Armies in early 1917; and in that position, he exercised overall direction of the German responses to British attacks at Third Ypres/Passchendaele (July 31 to December 7, 1917) and Cambrai (November 20–30, 1917).

Part of Rupprecht’s task was to construct the latter famed Hindenburg Line defensive positions. This was an attempt—codenamed Operation Alberich—to shorten the German-held area in front of the later Hindenburg Line so that less troops would be necessary to hold the area. Overall, it was a program of destruction designed by Ludendorff that included houses demolished, wells poisoned, trees cut down, booby traps and mines planted, and also large segments of the Allied populations evacuated. At first, Rupprecht determined that he would resign over what he considered to be a monstrous order, then, on second thought—because he was who he was in wartime—he merely refused to sign the order himself. Thus, responsibility was averted.

In July 1917, the flinty heir to Munich’s throne demanded in conference that Ludendorff should stick with his military knowledge and avoid politics. By September 1917, the Bavarian crown prince was also calling privately for the evacuation of Belgium to placate English fears of a later German seaborne invasion of the British Isles, and also perhaps to help save the Hohenzollern dynasty thereby.

In 1917, there occurred the Third Battle of Arras along with the Battle of Flanders, called later by its German survivors “The most difficult of all defensive battles. The point of the Battle of Flanders was to hit the (German Navy) submarine base of Zeebrugge, and that this failed was in part credited to Crown Prince Rupprecht.”

In February 1918—observing events unfolding on the Eastern Front from afar—Rupprecht warned against the joining of Litauen, Kurland, and other parts of Russia with Prussia politically. When his advice was ignored, Rupprecht wrote in a letter the following September of “The ostrich-like attitude—a lie in itself!—that was already noticeable in the politics of the prewar years, and is the reason for our military defeat.”

“Everyone who speaks up against this is [branded] a pessimist and a weakling,” he noted of the doves like himself within the German Empire’s ruling strata, attests Blohm.

Militarily, Rupprecht was equally as outspoken as the spring 1918 offensive preparations were being made on the Western Front, arguing that there should be a push toward Hazebrouck-Calais. He asserted that, if it would have been possible to cut off the French, Belgian, and English troops who were standing along that east-west line, pushing them against the sea, as well as to gain the west coast from Ostend to Le Havre, it would have meant the fall of the British and the overall Entente alliance.

At the November 11, 1917 Mons Conference—ironically—there had first been discussed Ludendorff’s coming spring 1918 grand assault. Present among others were the first quartermaster general, Rupprecht’s chief of staff Gen. von Kuhl, von der Schulenburg for Imperial Crown Prince Wilhelm, and Col. Georg Wetzel to decide both the date and place of the initial attack, to be codenamed overall Michael.

As a reflection of how thoroughly the various chiefs of staff dominated their individual commanding officers, not a single one of them was in conference. It is doubtful that the presence of Rupprecht could have staved off the ultimate defeat. His influence could have meant more limited offensives that might have prolonged the war into either 1919 or 1920, or ended it sooner—say, in March 1918—without the gross casualties on both sides that it produced instead.

Once the overall series of attacks got underway, Rupprecht’s Army Group attacked at the Somme River during March 21 to April 4, 1918, launching as well the Lys Offensive of April 9–29, 1918 next.

Recalled Asprey in The German High Command, later: “After the withdrawal from the Marne, the first step was taken, and what had begun there four years ago as a victory march was now again become a defeat. Another attack of the troops in Flanders had to be discontinued after 18 July 1918, leading to the ‘Black Days of Compiegne.” On August 15, 1918, Rupprecht expressed his utter amazement regarding their newest enemy on the European battlefields: “The Americans are multiplying in a way we never dreamed of!… At present, there are already 31 American divisions in France!” This led even the normally bellicose Ludendorff to lament to von Kuhl on September 30, 1918, “We cannot fight against the entire world!”

In late October 1918, Rupprecht wrote to the new and last Imperial Chancellor Prince Max of Baden at Berlin:

Our troops are exhausted.… In general, the infantry of a division can be treated as equivalent to one or two battalions, and in certain cases, as only equal to two or three companies.… In certain armies, 50% of the guns are without horses.

The morale of the troops has suffered seriously, and their power of resistance diminishes daily. They surrender in hordes, whenever the enemy attacks, and plunderers infest the districts around the bases.

We have no more prepared lines, and no more can be dug. There is a shortage of fuel for the trucks, and when the Austrians desert us—and we get no more petrol from Rumania—two months will put a stop to our aviation!

Thus asserted the soldier who in 1914 had taken 12,000 enemy prisoners and fifty guns in his first battle. He was right: within a month, the overall German war effort collapsed, as well as all of the Second Reich’s dynasties in their wake on the home front. He ended the war by executing a skilled combat withdrawal through occupied Belgium against sustained and heavy British attacks during August to November 1918.

Crown Prince Rupprecht was now only an illustrious, unemployed former army group leader, a crownless prince without a future throne after the overthrow of his father at Munich.

Two of his former staff officers would find fame in the next world war, however: Col. Gen. Franz Halder as chief of the general staff and Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, both under the aegis of former 6th Army Group Cpl. A. Hitler.