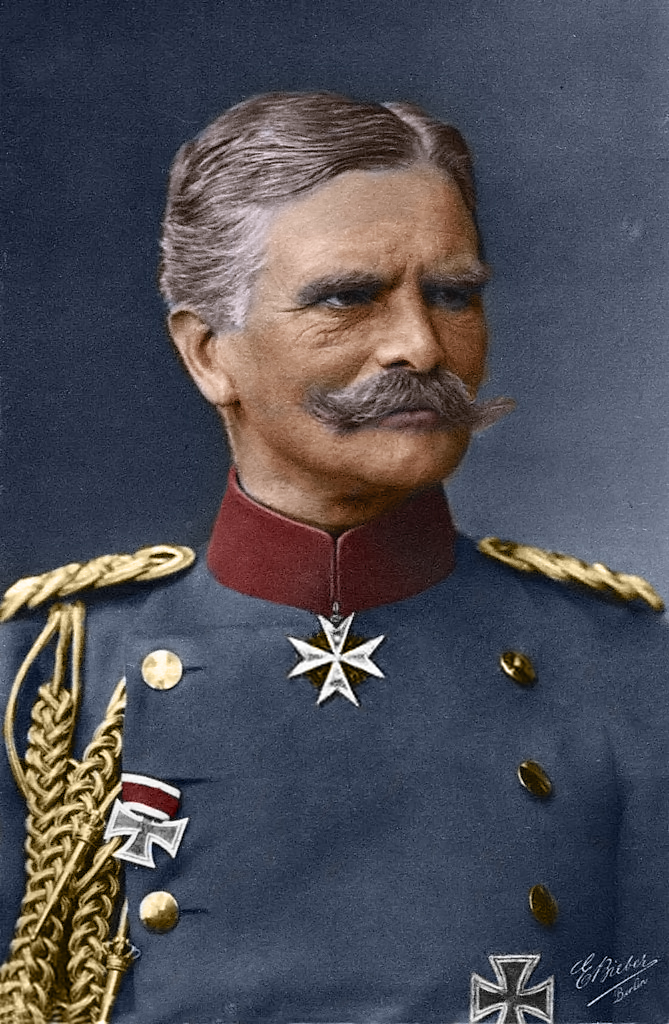

“He was bold in front of the enemy, and only feared God,” it was said of August von Mackensen, the Kaiser’s favorite soldier and the House of Hohenzollern’s last appointed general field marshal (GFM). So asserted the official 1938 work Prussian-German Field Marshals & Grand Admirals, published postwar in Berlin. As for the former sergeant of the Franco-Prussian War Battle of Sedan himself, when Kaiser Wilhelm II—his admiring patron—raised him to the nobility in 1899, the newly created August von Mackensen chose as his familial motto the simpler theme of “Memini initii” (“Remember the Beginning”), recalling his humble origins.

Indeed, his British critic Cyril Falls called him “One of the most over-advertised generals of the war,” after reviewing how, in August 1914, the advancing Russians had taken 6,000 of his men prisoners, before he was able to halt in his personal command car their 15-mile-long rout to the rear, at Gumbinnen.

In addition, Falls asserted: “He used to boast of his descent from a Highland chieftain, a Mackenzie. When this became unsuitable, it was given out that his name was derived from the village of Mackenhausen.”

The 1938 Prussian-German Field Marshals & Grand Admirals stated: “The Mackensens were farm people from Solling in Niedersachsen, where the Village of Mackensen was probably the birthplace of the Mackensen lineage. His father Ludwig was a farmer who worked hard, and went from leasing a parcel of land to owning an estate. His mother—Marie Rink Mackensen—gave birth to her eldest son Anton Ludwig Friedrich August on 6 December 1849 in Leipnitz, Sachsen.”

The future Saxon warrior against Russians, Serbs, and Romanians in the Great War as—earlier, against the French—played with toy soldiers as a boy and dreamed of a military career, just like his later superior, rival, and ally, Hindenburg.

Since his father could not afford to send him to a military academy for officer training, young August instead took a one-year enlistment as a volunteer on October 1, 1869 with the 2nd Lifeguard Hussars.

When war broke out with Imperial France in July 1870, Mackensen fought at Sedan and led a reconnaissance patrol that resulted in his division commander personally nominating him for the Iron Cross.

That December 4, he took several French prisoners, and on the 12th, he was promoted from the ranks to lieutenant in the Royal Prussian Army Reserves, a single step up. In 1873, Mackensen was named lieutenant of the Lifeguard Hussars, three years later as adjutant to 1st Cavalry, and promoted first lieutenant in 1878, being chosen two years later for the prestigious German general staff as well.

Promoted captain in 1882, he was named to the general staff of the 14th Division in 1885, and two years later as Chief of Dragoons for Regiment No. 9. That same year, his friends gave him a plaque with the inscription “For Capt. Mackensen: who will advance with lightning speed and become a General Field Marshal”; prophetic words, indeed, for one who would later also assert that he wore the same uniform size throughout his entire military career.

Named major in 1888, three years later, Mackensen was adjutant to the influential Chief of the German General Staff Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Schlieffen. This brought him into the regular circle of the Kaiser, with whom his career, fate, and destiny would forever be linked through two world wars. Mackensen angered his contemporaries by kissing the Kaiser’s hand.

Mackensen was promoted lieutenant colonel in 1894 as commander of the 1st Lifeguard Hussar Regiment, and in 1897, he was jumped to full colonel. The following year witnessed his promotion to the post of senior adjutant to the Kaiser, and after his ennoblement, his children were entitled to inherit his “von,” as the male members did. He had three sons and a daughter.

The future field marshal was married twice. After the death of his first wife, Doris von Horn, he married Leonie von der Osten, twenty-eight years his junior.

After having accompanied the Kaiser to Palestine in 1898, Mackensen was promoted to major general in 1900, and the next year received the plum Lifeguard Hussars Brigade appointment at Danzig, where he remained until the war began in 1914.

In 1903, von Mackensen had been named lieutenant general as commander of the 36th Cavalry Division, and five years later, he was again promoted to general of cavalry and commander of the 17th Army Corps.

On July 17, 1914—at the age of sixty-five and seemingly on the verge of retirement after a most successful military career, the majority of it in peacetime—fate intervened, and August von Mackensen took his place on the martial stage as a great captain in the most stupendous conflict in all recorded history to that date.

The 17th Corps that he had already commanded for six years prior to the outbreak of World War I encompassed a pair of divisions of eight infantry regiments, one battalion of Jägers (Sharpshooters), three regiments of cavalry Hussars, the 4th Regiment of Mounted Rifles, two brigades of field artillery, Corps heavy artillery reinforced with pioneer/engineer troops, and the aerial 17th Detachment for reconnaissance.

The corps commander’s headquarters was located at Deutsch-Eylau, later relocated to Darkehmen.

On August 15, 1914, it was the Tsarist Imperial Army that surprised the world by launching an offensive into the Kaiser’s own backyard in Prussia, winning the Battle of Gumbinnen on August 20, 1914 against none other than 17th Corps Commander Gen. von Mackensen, defeating the German emperor’s favorite horseman, thereby knocking his units into a headlong retreat.

Noted Ludendorff’s Own Story:

The infantry lost 200 officers and 8,900 men in combat, as well as 1,000 prisoners-of-war [to the victorious Russians]. Two batteries daringly advanced very far forward to help the infantry, but were annihilated, losing 13 officers and 150 men.

The headquarters itself with its park of cars and horses of the escort was taken under Russian artillery fire.… The infantry lost more than a third of its strength killed and injured.… The Russians were content to pursue the retreating Prussians with their artillery fire.

It was this loss that caused his superior—German 8th Army C.O. Gen. Prittwitz und Gaffron—to consider abandoning East Prussia altogether to the two invading Russian armies, via a pell-mell retreat behind the Vistula River instead.

Still, the beaten but determined von Mackensen promised to tell the Kaiser in person of the bravery of the many soldiers who had stood and fought during the mêlée, closing his oration with the exhortation, “Whatever the future can bring us—for His Majesty the Emperor and King, hurray!” Still, the very first German defeat of the war in the east had been his. Von Mackensen’s role at Tannenberg was to attack the Russian right wing at Bischofsburg and Sensburg in what today is Poland.

Expunging somewhat his humiliating defeat at Gumbinnen a few days before, he both broke and pursued it in his characteristically aggressive fashion.

At the follow-up First Battle of the Masurian Lakes of September 9–14, 1914, southeast of Königsberg in East Prussia, the redeployed German 8th Army of his superiors pursued Rennenkampf’s twelve divisions, resulting in a second German victory, with 10,000 German killed to the Russians’ 45,000 lost and 150 guns taken. Still, though, this 1st Russian Army escaped annihilation by retreating back into European Russia from whence it had so unexpectedly come.

Mackensen led from the front, and thus often higher headquarters did not always know exactly where his 17th Corps was, as he rejected orders that countermanded his own desires to keep pursuing the retreating enemy and—as at the Lötzen Gap—assaulted the Russians morning, noon, and night of the same day.

On October 9, 1914, the overall Russian commander, Grand Duke Nicholas (aged fifty-seven), threw fourteen Russian and Siberian divisions against Mackensen’s five, necessitating a fallback upon Łódź.

On November 1, 1914, von Mackensen was named commander of the 9th Army before Warsaw, with his 250,000 men facing double that number of the resilient enemy.

That December, von Mackensen’s forces retook Łódź and then Lvov in Poland, preparing for the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive breakthrough of May 2, 1915 before Warsaw. That April, he had been named commander of the 11th Army, as well as being promoted to the grade of colonel general.

Asserted Asprey in The German High Command: “Mackensen handled his forces well, relying as earlier on powerful artillery support against a confused enemy short of reserves. Though progress was slower at Gorlice because of limited roads, Mackensen continued to employ tactics built around a strong center of heavy guns.” He had learned from his mistakes at Gumbinnen the year before. With the brilliant Gen. Hans von Seeckt as his chief of staff, von Mackensen stormed the Russian positions and won a victory on May 2, 1915.

On the following June 22, when Lemberg (Lviv) fell to his Austrian troops as well—the Kaiser promoted him at Castle Pless to the rank of general field marshal, thus reaching the pinnacle of his storied martial career.

On August 26, 1915, the newly minted general field marshal also took the embattled Russian Fortress of Brest-Litovsk that would assume a diplomatic role during 191718. He was honored as well with the command of the Austro-Hungarian Army Hussar Regiment No. 10, backdated to June 11, 1915.

Three days later—on August 29, 1915—Prince Leopold of Austria succeeded Hindenburg as Supreme Commander of All German Forces on the Eastern Front, with Gen. Hoffmann as his chief of staff. Reportedly, His Bavarian Majesty retained this command until the end of the war and was also a potential German candidate for the throne of the puppet Kingdom of Poland that never materialized. Prince Leopold ended his military career with more success, therefore, than did some other GFMs of the period; he died on September 28, 1930 and is buried at the Columbarium of St Michael’s Church at Munich.

When it was announced that there would be a combined German-Austrian-Bulgarian invasion of Serbia under von Mackensen—the Serbs had already beaten the hapless Austrians twice—Hoffmann noted sourly, “Now that all available honors, titles, and orders have been showered in so short a time on this one devoted head, there will be nothing left for him after the capture of Belgrade but to be re-christened Prince Eugene!” after the famous Austrian commander of yore.

Explained Asprey, “Field Marshal Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663–1736) was Austria’s ‘noble cavalier,’ a heavily decorated (and richly rewarded) military and political genius, gray eminence to Kaiser Karl VI, and builder of Vienna’s beautiful Castle Belvedere.”

Mackensen’s combined force had as its core nine German Army divisions, as of September 16, 1915. The Serb capital of Belgrade duly fell to his forces on October 9, 1915, and both he and von Seeckt wanted to push on to Salonika in Greece, but the now so-called Palatine of the Balkans was overruled by Supreme Headquarters in favor of a joint attack into Romania with Gen. Erich von Falkenhayn in September 1916 instead.

Mackensen crossed into enemy Dobrudja on September 4, 1916, destroying Fortress Tutracaia on the Danube River, even though his force was smaller than its garrison. Next, he took forced marches on to Fortress Silistria, 70 miles southeast of Romania’s capital city of Bucharest.

Linking up with von Falkenhayn, Mackensen managed to enter the next captured enemy capital ahead of his co-warrior—riding in on a white steed like the showoff cavalryman that he had always been—on December 6, 1916, the acclaimed hero of the Central Powers once more, and, as always, the cherished martial darling of the Kaiser.

Indeed, the startled Kaiser declared that he would name the next German naval battle cruiser after his battlefield pet, but this never occurred. The glorious commander had been awarded the Blue Max on November 27, 1914, its ninth awardee of the Great War, and also held both the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Classes.

In January 1917, the black-clad soldier in the Death’s Head fur busby was also granted the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, its other distinguished holders being Hindenburg, Ludendorff, and Field Marshal Prince Leopold of Bavaria.

Naturally—as in all armies from time immemorial—all this notoriety only increased the professional jealousy of von Mackensen’s successes, even on May 26, 1917 by his former subordinate and supposed admirer, Imperial German Crown Prince Wilhelm, who believed he was “Quoted far too often.”

The other strains of the long war were already being felt, however, as noted by Navy Adml. Karl von Müller in his wartime diary entry for September 22, 1917: “Mackensen’s deputy … reports that the tension between the Bulgarian troops and our own in the Dobrudja is very serious, and that hostilities can start at any moment. King Ferdinand’s warning to Mackensen should not be dismissed lightly.”

When an armistice was announced with Romania on March 2, 1918, the admiral further recorded this entry: “The Dobrudja will not be ceded to Bulgaria, but to the Central Powers, who will come to a decision on its future at a later date. We—Germany—want to retain the use of the Cernavodă-Constanţa Railway.… Thank God Mackensen was there, or else things would not have been dealt with so summarily.”

In his multiple successful martial operations, the Black Marshal was quick to acknowledge in his postwar 1938 memoirs the services of his triad of talented Chiefs of Staff: Col. Hans von Seeckt in his Serbian campaign, the transitional Lt Col. Richard Hentsch, followed by his permanent Romanian Campaign C of S, Lt Gen. Gerhard Tappen