Many government officials particularly criticized Mussolini for his mild treatment of Amedeo Adriano Bordiga. It was deemed too extreme even for his fellow Marxists, who expelled Bordiga from the Italian Communst Party; he was briefly interned in 1925, later freed under police surveillance.

The last arrests of Giustiziae e Liberta adherents had just been made when Mussolini received Franco’s request for help to defend his country from the same internal forces that bedeviled Italy. The Duce was hardly alone in his concern for events in Spain. They deeply touched most Italians, who regarded the Spaniards as not only fellow Latins, but Catholics suffering a wave of church desecrations and bloody atrocities at the hands of a militantly atheist government. People worried that the Russian calamity of 1917 was about to repeat itself, and this time not that far away. They clamored for a modern crusade to extirpate the Communist infidel from Western European soil.

But Italy’s military had been worn out by the Abyssinian experience. The Army and Air Force were in need of refitting. Mussolini was at first able to spare Franco only nineteen warplanes, which would be up against far more enemy aircraft. These included sixty French Breguet XIX reconnaissance bombers, forty Nieuport-Delage Ni.52 fighters, fourteen Dewoitine D. 371 and ten D.373 pursuit planes, plus 65 Potez Po.540 medium bombers, together with twenty British Vickers Wildebeest torpedo-bombers. Aiding the Italians were nine, wheezing biplane fighters which comprised the entire Nationalist Air Force, and ten German tri-motor transports.

On 29 July, the Morandi sailed from La Spezia for Melilla, a port in Spanish Morocco. The large freighter carried abundant supplies of ammunition, bombs, aviation fuel and aircraft for Franco’s forces. The next day, a flight of nine Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers landed at Nador outside Melilla, the first of some 720 aircraft and 6,000 aircrews Mussolini dispatched to the Nationalist cause. They were intended to support the more than 70,000 Italian soldiers that would eventually serve in Spain.

Throughout most of the Spanish Civil War, the Republicans continued to enjoy a numerical edge over their opponents, thanks to help from Russia and covert armaments smuggled across the Pyrenees by a sympathetic French Premiere, Leon Blum. At the behest of the League of Nations, along with most other world leaders, he had signed a non-intervention agreement that excluded outside involvement in the Civil War for the expressed purpose of containing hostilities in Iberia, thereby preventing them from widening into a general conflict. Although publicly avowing non-participation in the sharply drawn ideological struggle, Blum covertly slipped French arms and supplies to the Republicans, and allowed his border patrols to look the other way when leftist volunteers wanted to cross the mountains into Spain.

But other heads of foreign governments likewise paid little more than lip-service to official non-participation. U.S. President, Franklin Roosevelt, who vigorously condemned the Nationalists, did not prevent thousands of Americans from joining something called the ‘Abraham Lincoln Brigade’. This was an armed assortment of socialist intellectuals, fire-breathing Communists, bored dilettantes, desperately unemployed men, one-world idealists, and Jews alarmed at the rise of European anti-Semitism who fought on the Republican side.

With its Wagnerian name, Operation Feuerzauber (‘Magic Fire’) was supposed to have been nothing more than a training exercise provided to Franco’s mechanics by a handful of German aeronautical ‘advisors’ at the Tablada airfield, near Seville. From these humble, thinly disguised beginnings, however, a Kondor Legion of Messerschmitt fighters and Stuka dive-bombers swiftly evolved. League of Nations deputies entrusted with international enforcement of the non-intervention agreement had no control over Mussolini after he stomped out of their Geneva headquarters over the Ethiopian affair, and the Soviet Union was not a member, never having been asked to join, so neither Italy nor Russia were constrained from sending men and equipment to Spanish battlefields and airfields.

Republican warplanes unquestionably dominated the skies from the beginning of the conflict. But they were challenged during August by the arrival in Seville of Savoia Marchetti and Caproni Ca.135 aircraft in two bomber squadrons. Together with the original dozen Fiat fighters dispatched by Mussolini, they comprised an early nucleus for the Italians’ Aviazione Legonaria, which eventually fielded 250 aircraft of various types. And their pilots would achieve distinction as the world’s best during the mid-1930s.

Some, like Maresciallo Baschirotto, became aces, shooting down at least five enemy a piece. His experience in Spain prepared him for duty in World War Two, when he destroyed six more Curtiss P-40s, Beaufighters, and Hawker Hurricanes during the North African Campaign. Baschirotto’s last victory was over a Spitfire near the island-fortress of Pantelleria, on 20 April 1942. “It was a happy birthday present to the German Führer,” he told a reporter for one of Italy’s oldest, most widely read newspaper, the Corriere della Sera.7 Hitler had on that day celebrated his 53rd birthday.

His comrade in Spain was Group Commander Ernesto Botto, who received the Gold Medal for downing four Republican aircraft. Although he lost a leg during their destruction, he volunteered for frontline flying two years later, when Italy went to war against Britain. Botto went on to claim another three ‘kills’ in the skies over the Libyan Desert, earning him the nickname, Gamba di Ferro, or ‘Iron Leg’.

The aircraft men like Maresciallo Baschirotto and Ernesto Botto were supposed to fly for Franco were not always as physically fit as themselves. The SM.81, for example, had already seen service during the Abyssinian Campaign in transport and reconnaissance duties. Its three 700-hp Piaggio P.X RC.35 nine-cylinder radial engines gave the Pipistrello, or ‘Bat’, as the rugged aircraft was affectionately known by its crews, 340 km/hr at 9,800 meters, with a range of 2,000 kilometers carrying a bomb payload of 1,000 kilograms–not bad for 1936. The Caproni was a more modern, twin-engine medium-bomber with a sleek fuselage and twin-boom tail. Faster by 60 km/hr than the Pipistrello, and able to deliver an additional 1,000 kilos of bombs, its three 12.7mm machine-guns in nose, dorsal and ventral turrets foreshadowed future developments.

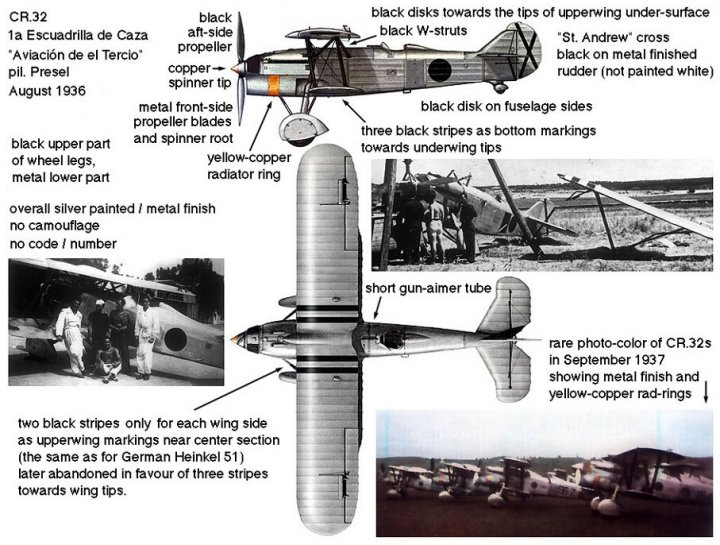

For escort, the bombers were protected by the Fiat CR.32, generally considered the best pursuit model at the beginning of the war, “soon gaining a reputation as one of the outstanding fighter biplanes of all time,” according to British aviation historian, David Mondey.8 Agile, quick and tough, the Fiat’s extraordinary aerobatic characteristics and top speed of 375 km/hr at 3,000 meters enabled its pilots to take on maneuverable ‘double-deckers’ like itself, such as the Soviets’ Super Chata, or more modern monoplanes, including the formidable Mosca. Eventually, 380 CR.32s participated in the Spanish Civil War. But during the conflict’s first months, just a handful of Italian bombers and fighters were General Franco’s first and, for some time, only support aircraft. Terribly outnumbered as they were in 1936, their technological superiority over the Republicans’ French and British machines, together with the Ethiopian experience of their aggressive crews, made the Aviazione Legonaria a force to be reckoned with from the start.

During late August 1936, the Italian airmen launched their first sorties against enemy strongholds in the north, where the Fiats swatted Nieuports and Dewoitines, while the Pipistrellos and Capronis were dead-on target with their destructive payloads. To combat these intruders, a famous French Communist author, Alfred Malraux, helped raise twelve million francs for the purchase of new warplanes as needed additions to his Escuadrilla Espaía. Based in occupied Madrid, his fiery oratory attracted foreign volunteer pilots from France, Britain and Czechoslovakia. Not to be outdone, Mussolini rushed additional squadrons of CR.32s to Seville.

They arrived just in time to confront a major enemy offensive during September, and contributed decisively to the battle. Malraux’s elite squadron was badly mauled, as the Popular Front offensive folded under the bombs of SM.81s and CA.135s. By December, with half its aircraft destroyed, the Escuadrilla Espaía disbanded; survivors melted into the regular Republican Air Force. Replacements came in the form of fifty Russian SB-2 Katuska bombers and I-15 Chata fighters. Later, after the New Year, Leon Blum quietly slipped another twenty state-of-the-art Loire 46 pursuit planes across the Pyrenees. More troublesome for the Italians was the appearance of a remarkably advanced Soviet bomber, the Tupelev SB-2, over Cordoba. It was faster than the quick Fiats, and could even out-climb them after dropping its bombs.

For weeks, the unassailable Tupelevs ranged over Nationalist territory, wrecking havoc on troop concentrations and supply depots. All attempts to intercept them met with failure. In January 1937, a Spanish pilot, Garcia Morato, noticed that the bombers were in Cordoba skies every morning at precisely the same time and altitude. Jumping into his CR.32 before they arrived, he climbed to 5,030 meters, well above the lower-flying enemy. They appeared like clock-work, and Morato pounced on them, his 7.7mm Breda machine-guns blazing. Two of the swift Russian aircraft fell flaming to earth, and the rest frantically jettisoned their payloads to beat a hasty retreat. Nationalist fighter pilots learned from his experience. If they were given sufficient advance warning, their Fiat fighter-planes, with remarkable service ceilings of nearly 8,840 meters and a swift rate of climb, could dive on the redoubtable Tupelevs from above.

But the speedy bombers were not the only quality aircraft sent from the USSR. Squadrons of nimble biplane fighters, the Polikarpov I-15, arrived in Madrid, together with numbers of an altogether different design, the I-16. The stubby monoplane more physically resembled a trophy-racer of the era than a military machine. It was the product of a prison experience endured by Dmitri Gregorovich and Nikolai Nikolayevich Polikarpov.

By late 1932, their new I-15 was despised by Red Air Force test-pilots unhappy with its instability at high speeds, and its gull-wings which prevented the airmen from seeing the horizon while in flight and obscuring the ground on approach, making landings hazardous. Enraged by the negative reports of his test-pilots, Stalin threw Russia’s leading aeronautical inventors into prison, together with every member of their design teams, until they came up with a fighter for the Soviet Union at least as good as contemporary examples from other nations. With their freedom and, ultimately, their lives at stake, the hapless engineers, still behind bars, put their heads together for the creation of an aircraft ahead of its time.

The I-16’s successful debut on New Year’s Eve 1933 coincided with the designers’ release from behind bars. An innovative, retractable landing-gear made it the first monoplane of its kind to enter service. The cantilever, or internally braced, low metal wing, plus all-wood monocoupe fuselage, resulted in a solid form easy to maintain in frontline conditions, able to take terrific punishment, and strong enough to survive the high-speed maneuvers that broke apart lesser aircraft. As one commentator observed, “its rolls and loops could be quite startling.” Powered by a 1,000-hp M-62 radial engine, Polikarpov’s best effort flew higher by 670 meters and faster by 115 km/hr than Italy’s finest fighter, and totally outclassed the Heinkel 51, Germany’s early rival for Spanish skies.