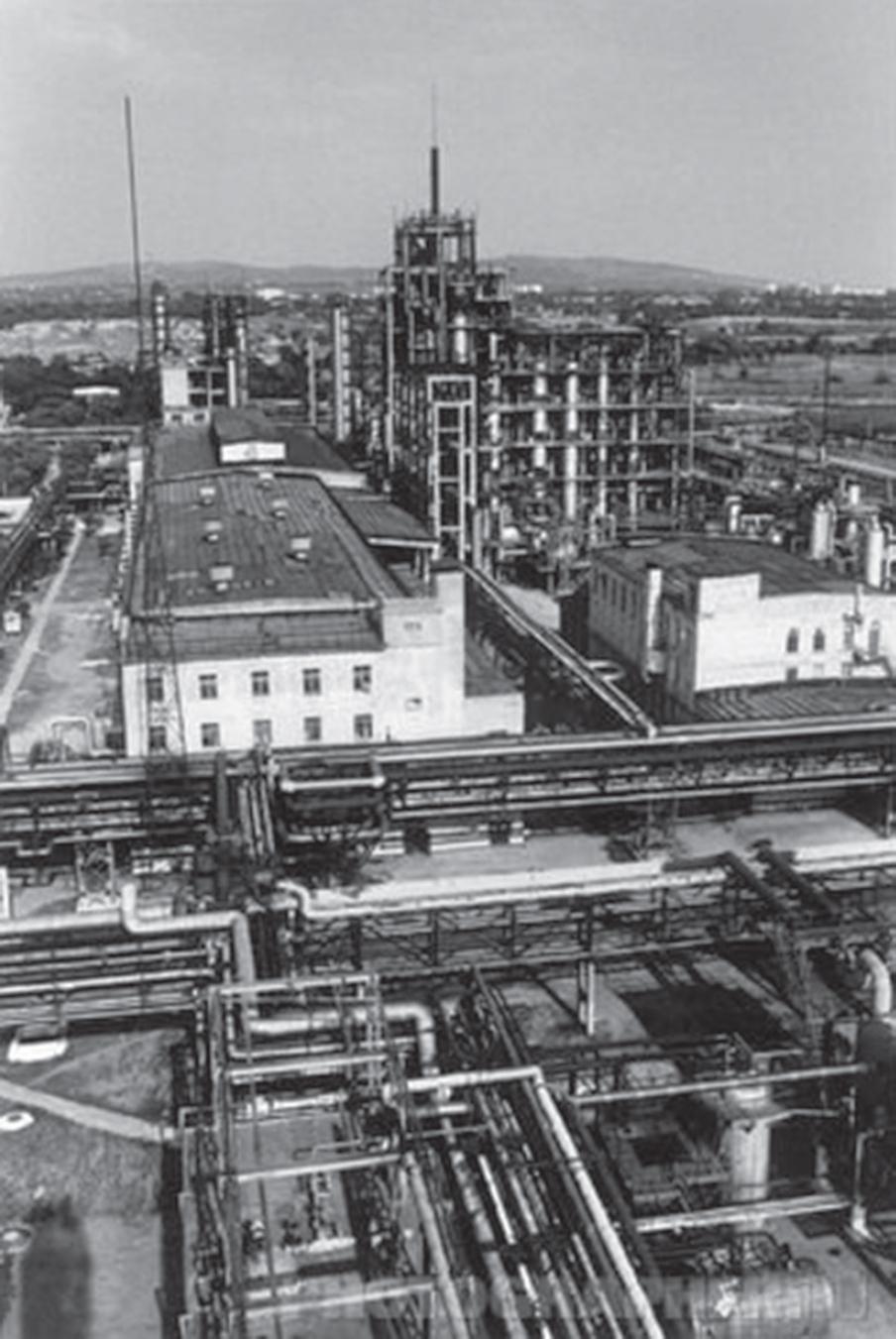

The ‘Lenin’ oil refinery in the city of Grozny.

Even before the Second World War, the Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess formulated the Nazi concept of ‘total espionage’. It consisted of three fundamental precepts: ‘Everyone can be a spy’, ‘Everyone should be a spy’ and ‘There is no secret that cannot be known’. These ideas became particularly relevant in early 1942, when Hess himself was already in a British prison. After the failure of Operation ‘Barbarossa’, the Third Reich found itself in a total war. Now it was necessary not only to collect intelligence in the vast area from the Arctic to the Caucasus, but also to organize sabotage operations in the rear areas of the Soviet Union. The leadership of the Security Service of the Third Reich (RSHA) believed that the Abwehr could not cope with these missions and decided to take the matter into their own hands.

By order of the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler a special intelligence agency code-named ‘Zeppelin’ was established on 15 February 1942. It was entrusted with the mission to weaken the military and economic potential of the USSR by organizing sabotage, acts of terror and uprisings behind Soviet lines. Its management was entrusted to Walter Schellenberg, the SD’s chief of foreign intelligence. Otto Skorzeny, the master of sabotage, was involved in planning specific operations and missions. The Abwehr was ordered to provide full support to the ‘Zeppelin’ project.

The initial manpower for this system of ‘total espionage’ was to be tens of thousands of volunteers from among Russian prisoners of war. In all camps there were offices and recruitment points for ‘Zeppelin’, whose employees closely studied the available personnel. As a result of vigorous work, according to German sources about 15,000 men had been recruited by the end of 1942. All of them were trained in the network of sabotage and intelligence schools established by ‘Zeppelin’ in that same year. There were sixty such schools in all, the largest being near Warsaw, Breslau, Yevpatoria (Crimea), Smolensk and Pskov.

‘The Age-Old Russian Yoke’

Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union was enthusiastically welcomed by many inhabitants of the Caucasus. This mountainous region had been ruled by the Russian Empire since the seventeenth century, but always remained rebellious. At the slightest weakening of Russian control, uprisings broke out. At the same time, the highland people themselves were constantly at war with each other, literally cutting each other’s throats with daggers. Both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union used this mutual hostility to govern the Caucasian provinces by ‘divide and rule’. Supporting one group against another, the Russians secured control over this breakaway region. The Soviet leader Joseph Stalin also came from the Caucasus. He knew the local ‘customs’ and brutally suppressed any opposition. But even the bloodthirsty Stalin failed to completely eliminate Caucasian separatism!

Operation ‘Barbarossa’ was seen by the Caucasian rebels as a chance to throw off the ‘age-old Russian yoke’. The centre of the ‘liberation struggle’ was Chechnya, where nationalist sentiments were particularly strong. The leader of the Chechen fighters, Hassan Israilov, was a legendary figure. He was born in 1903 in one of the mountain villages of Chechnya, and his family clan had an illustrious history. His grandfather Israilov was Naib (deputy) to the legendary Shamil, who led the uprising against Russia in the nineteenth century. Israilov’s father had ‘heroically’ died in the robbery of the Treasury Bank in Kizlyar. From his early youth, Israilov followed in the footsteps of his ancestors, continuing the ‘family business’. He was arrested four times and sentenced to 10 years in prison and even to death, but his relatives regularly paid bribes to have him released. All this did not prevent the proud Highlander from joining the Communist Party!

In 1933, Hassan Israilov suddenly ‘repented’ and promised to serve the Soviets from then on. For a short time he worked as a correspondent and party investigator (!), wrote poetry and studied at the Communist workers’ ‘Stalin’ University. At the same time, Israilov formed a gang and robbed a bank. The bandits killed two guards and, cutting off their hands, folded them in the form of two letters ‘M’. This meant ‘Mecca’ and ‘Medina’, the names of holy cities for Muslims.

Soon Israilov was arrested again and sent to prison in Siberia. The Soviets were lenient with bandits and thieves. While political prisoners and completely innocent citizens suspected of opposing views were brutally tortured and executed, bandits and murderers received soft sentences and were kept in normal conditions. Israilov fled the camp, killing a guard and two dogs. He cut ‘steaks’ from them, which he ate while wandering on the Siberian taiga. Returning home to Chechnya, Israilov organized terrorist attacks, sabotage and the destruction of collective farms (kolkhozes).

In 1940, Hassan Israilov headed the ‘Chechen National Liberation Movement’. The uprising was successful, and soon in the mountainous part of Chechnya Soviet power was virtually eliminated. Deserters and local residents joined the army of the ‘second Shamil’. The attack by Nazi Germany gave the rebels new strength, and on 23 June 1941 they even declared war on the Soviet Union.

In September 1941, Israilov together with his associate Basayev organized a major uprising in the Shatoy district. In November, in anticipation of the imminent arrival of the Germans, mass uprisings began in Kabardino-Balkaria, North Ossetia and Dagestan. The NKVD were powerless against the mountaineers, and a number of senior officers, particularly the head of the NKVD of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR Albogachiev and the head of Department on struggle against gangsterism Aliyev, went over to Israilov.

The Main Sponsor of the ‘Rebels’ Comes into Play

The German secret service soon became aware of the ‘liberation movement’ in the Caucasus. In 1941, theAbwehr did not have the resources to support the warlike highlanders, but things changed in 1942, when the Caucasus region with its rich oil fields became the target of a new Wehrmacht offensive. By supporting the rebels, the Germans hoped to undermine the rear of the Red Army, and ensure the rapid capture of the oil fields and refineries to prevent their destruction by the retreating Soviet troops.

Under the auspices of the RSHA and the Reichsministerium für die besetzten Ostgebiete (RMfdbO – Reich Ministry of the Eastern Territories), several ‘national committees’ were created, which played the role of ‘governments in exile’. Among them were Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Kalmyks and many other nationalities. They were instructed to recruit volunteers from among the prisoners, defectors and emigrants to conduct subversive activities behind Soviet lines.

In April 1942 under Einsatzgruppe ‘D’ special group ‘Zeppelin’ was formed in Simferopol (Crimea). Agents were recruited in the local PoW camps, with preference given to ‘persons of Caucasian nationality’. In neighbouring Yevpatoria, in the former NKVD children’s sanatorium, the Germans created a reconnaissance and sabotage school to train agents in two main roles: ‘scout-saboteurs’ and ‘organizers of rebel movements’. A total of 200 recruits in five classes were trained for a period of four months. The first graduations took place in August, and soon a group of six Ossetians flew to the North Caucasus.

With the help of Caucasian agents, the Wehrmacht seized an oil refinery in the Maikop area. German paratroops prevented its destruction. In the summer and autumn of 1942, an ‘air bridge’ operated for the delivery of agents into the Caucasus. From the airfield at Saki in the Crimea transport planes flew almost every day with new groups, loaded with radios, weapons and other equipment.

In August, the First Panzer Army launched a rapid offensive in the Caucasus. By 21 August, German mountain troops hoisted the Nazi flag on the top of Mount Elbrus, and the XL Panzer Corps, quickly crossing several rivers and capturing Voroshilovsk (now Stavropol), reached the banks of the Terek river. In Chechnya, the rebels were expecting massive Luftwaffe attacks and landings of airborne troops. But the sky over the Caucasus remained surprisingly calm. This was due to the fact that on 11 August, the commander of Luftflotte 4, Generaloberst Wolfram von Richthofen, reported that the ‘Russian southern army’ had been destroyed. Then he began to concentrate the main forces of the Luftwaffe against Stalingrad. On 23 August, the German Sixth Army reached the Volga, and the city itself, named after Stalin, was subjected to continuous heavy air raids. Originally only III./JG 52 under Major Gordon Gollob was sent to Terek. As of 20 August, the group had forty-three Bf 109s, of which twenty-eight were operational. On 23 August, the first flight of a Bf 109 was recorded near Grozny, the capital of Chechnya.

German tanks halted on the bank of the Terek not because they met strong Russian forces there. They just ran out of fuel. For a month, the XL Panzer Corps simply ‘rested’, while the Soviets feverishly constructed a new line of defence in the area of Grozny. Only 40km away from the German tanks were huge reserves of oil and gasoline. Ironically, the Germans could not reach them because of the lack of gasoline …

In mid-September, the First Panzer Army was going to continue the offensive (Hitler promised to deliver gasoline). On 25 September, a mixed German-Chechen sabotage group led by Oberleutnant Helmut was landed near Grozny. After a brutal battle with the VOHR (private security) and NKVD guarding the ‘Lenin’ oil refinery, the group managed to capture the huge facility! Soon Chechen rebels came to the rescue and organized the defence of the plant.

The ‘Lenin’ plant was located on the outskirts of Grozny on the left bank of the Sunzha river. It was a huge facility, which included twelve refineries and a huge tank which held a million tons of oil. Around the plant there were many Soviet troops and several military airfields. However, they did not dare to immediately attack Lange’s group and the Chechens who joined them, fearing that a large-scale battle would destroy the plant. The Russians had orders from Stalin only to blow the plant up when German tanks were close. A few days later aircraft of 2./ Aufkl.Gr.Ob.d.L. delivered another unit under the command of Unteroffizier Schwaiffer to help Lange. One of its participants later recalled the drop: ‘The side door opens. And so the Legionnaires one after another rush into the darkness … the plane makes a second pass and drops by parachute containers. They contain weapons, ammunition and equipment for the rebels. Aircraft flashing signal lights and with a roar rushes back. Quietly and smoothly parachutes descend to the ground.’ As they came down the saboteurs were fired at from the ground, and only some of them were able to land unharmed and then get to the oil plant.

The German command promised Lange and his men that in the near future the XL Panzer Corps would reach Grozny. If the German tanks could break through by 30 September, Hitler would get the important plant undamaged, ready to supply fuel to all German military units on the Eastern Front. But the fuel promised by the Führer had not arrived. As a result, the Russians besieged the plant and drove out the saboteurs. Group Lange managed to escape into the mountains and join the Chechen rebels. By radio, the saboteurs reported their new location, and soon aircraft from the Rowehl Group delivered cargo containers containing 300 small arms, five machine guns and ammunition to them. After completing the mission, Group Lange after a while returned to the German lines. Two Chechens who formed the group’s rearguard were awarded the Iron Cross.

The Luftwaffe Comes to the Rescue

The German command soon realized that the attempt to capture the oil refineries and huge fuel tanks was going to fail. At the same time, they wanted to deny those reserves to the Soviets. As a result, it was decided to destroy the plant. On 9 October 1942 reconnaissance aircraft flew over Grozny three times at high altitude. The next day, from 12.40 to 14.00 several scouts again flew at high altitude over the city, including an Fw 189A.

The air defence of the Grozny was in the hands of the 105th Fighter Aviation Division (105th IAD PVO). It had been formed in early 1942 to protect the cities of Rostov and Bataysk. In July, this unit withstood a brutal and unequal battle with the Luftwaffe, which repeatedly bombed railway junctions and crossings over the River Don. When the Wehrmacht captured Rostov, the 105th IAD PVO was evacuated to Chechnya. In early October, the division consisted of four fighter regiments, which were based at the Grozny-5 and Grozny-8 airfields. In these units, there were forty-two serviceable aircraft (nineteen LaGG-3s, eight Yak-1s, five I-153s, four I-16s, four MiG-3s and two YaK-7Bs). None of these fighters even tried to intercept the German reconnaissance aircraft. The Russians were careless and did not suspect that these flights were the harbinger of the apocalypse!

At 14.02 on 10 October, Russian air surveillance posts reported that several groups of bombers, accompanied by Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters, were approaching Grozny from different directions. A few minutes later, an ‘Air alarm’ was declared in the city, and already at 14.05 over the outskirts the first group of twelve Ju 88As were over the outskirts of the city. The bombers approached the target from the south-western direction, following the Sunzha river. German fighters soon arrived, which loitered over the target and within a radius of 30km of it. Bf 109s immediately intercepted the fighters of the 105th IAD, which took off to attack the German bombers.

The attack was mainly carried out by dive-bombing and was extremely accurate. The Ju 88As dived on the target at an angle of 30– 60 degrees, and then escaped at low altitude. According to the Russian rescue service, of the 400 bombs dropped, only 25 fell on the city, the rest on the ‘Lenin’ Plant and other facilities in the Stalin district of Grozny. As a result, the refinery, pumping station, power station and eighty fuel tanks, 200 installations in total, caught fire! The biggest oil tank with a million tons of oil blazed. Like lava from a volcano, oil flowed into the Sunzha river and the city. Burning oil melted even the tram lines and burned everything in its path.

Against the attack twenty-six fighters took off, including eight LaGG-3s of the 822th IAP PVO. However, this was barely more than a demonstration. Even the command of the 105th IAD recognized that the actions of the interceptors were ineffective: ‘Due to the small number of our fighters, it was impossible to provide effective counteraction to all echelons of bombers. Our fighters attacked the 1st and 2nd echelons and, having started a fight with bombers and enemy fighters, were not able to effectively attack the subsequent echelons of the enemy.’ In addition, attacking bombers over the city would have hindered the anti-aircraft fire. And yet Russian pilots claimed aircraft shot down (ten Ju 88s and one He 111), six of them by the 822th IAP. ‘Hero of the day’ was Sergeant G.K. Martys, who first shot down one of the Ju 88s at close range, and then rammed another bomber with his LaGG-3. Troops on the ground witnessed this.

But, according to German information, during the massive raid on Grozny (it had involved all the available bombers of Luftflotte 4) only a single plane was lost, Ju 88A-5 W. Nr. 8282 ‘V4+BH’ of 1./KG 1. Probably, this was the aircraft rammed by Martys.

The second raid on Grozny began at 18.47, which lasted with pauses until 00.10 on 11 October. It was carried out by He 111H-6s from I./KG 100. This time the Russian interceptors did not take off ‘due to lack of night flying experience’. The attack was opposed only by the anti-aircraft gunners, who at the end of the day claimed six aircraft shot down.

At 11.05 on 11 October in Grozny, the sky over which was thick with the smog from the huge fires, a pair of YaK-7Bs piloted by Senior Sergeants Kuzmichev and Smirnov of the 182th IAP intercepted and shot down a Ju 88 at an altitude of 5,500m (18,000ft). It was a Ju 88D-5 W. Nr. 430044 of 2.(F)/Ob.d.L, which had been sent to photograph the results of the bomb attack. The plane was damaged and made an emergency landing near Mariupol. Three members of the crew were injured.

At 20.25 on the same day the Luftwaffe carried out a third raid on Grozny, dropping another 100 large high-explosive bombs on the refinery. At 20.30m Captain Kovalchuk of the 182th IAP took off from the Grozny-8 airfield. Soon, at an altitude of 3000m (10,000ft) above the southern outskirts of the city, he saw an He 111, illuminated by searchlights. Approaching it at a distance of 300m, Kovalchuk gave a prearranged signal – a sequence of tracer bullets, meaning ‘attack’. Anti-aircraft artillery ceased fire, Kovalchuk brought his LaGG-3 to within 50m of the bomber and shot it down. The Russians reported that the burning bomber crashed 17km north-west of Grozny. Major Batik, commander of the 182th IAP, who took off in an LaGG-3 after Kovalchuk, tried to attack a German plane over the north-eastern outskirts of the city, the opposite side to Kovalchuk. But he was illuminated by searchlights and fired on by the anti-aircraft guns. They did not react to the signal ‘I am a friendly aircraft’, so Batyuk had to carry out evasive manoeuvre instead of attacking and return to base. Kovalchuk’s victory is not confirmed by German sources.