The Hungarian tribes were the first steppe peoples who managed to develop into a strong nation with the capacity to adapt, and possessing self-awareness as well as historical self-confidence. How, in detail, the land came to be occupied is as little known as the fate of the inhabitants. In Nation and History Jenö Szücs opines that the local ruling class was probably annihilated, while the masses were assimilated and within two to three centuries fused with compatible social strata: warriors with warriors, slaves with slaves and so on. Of prime importance were common lifestyle and interests.

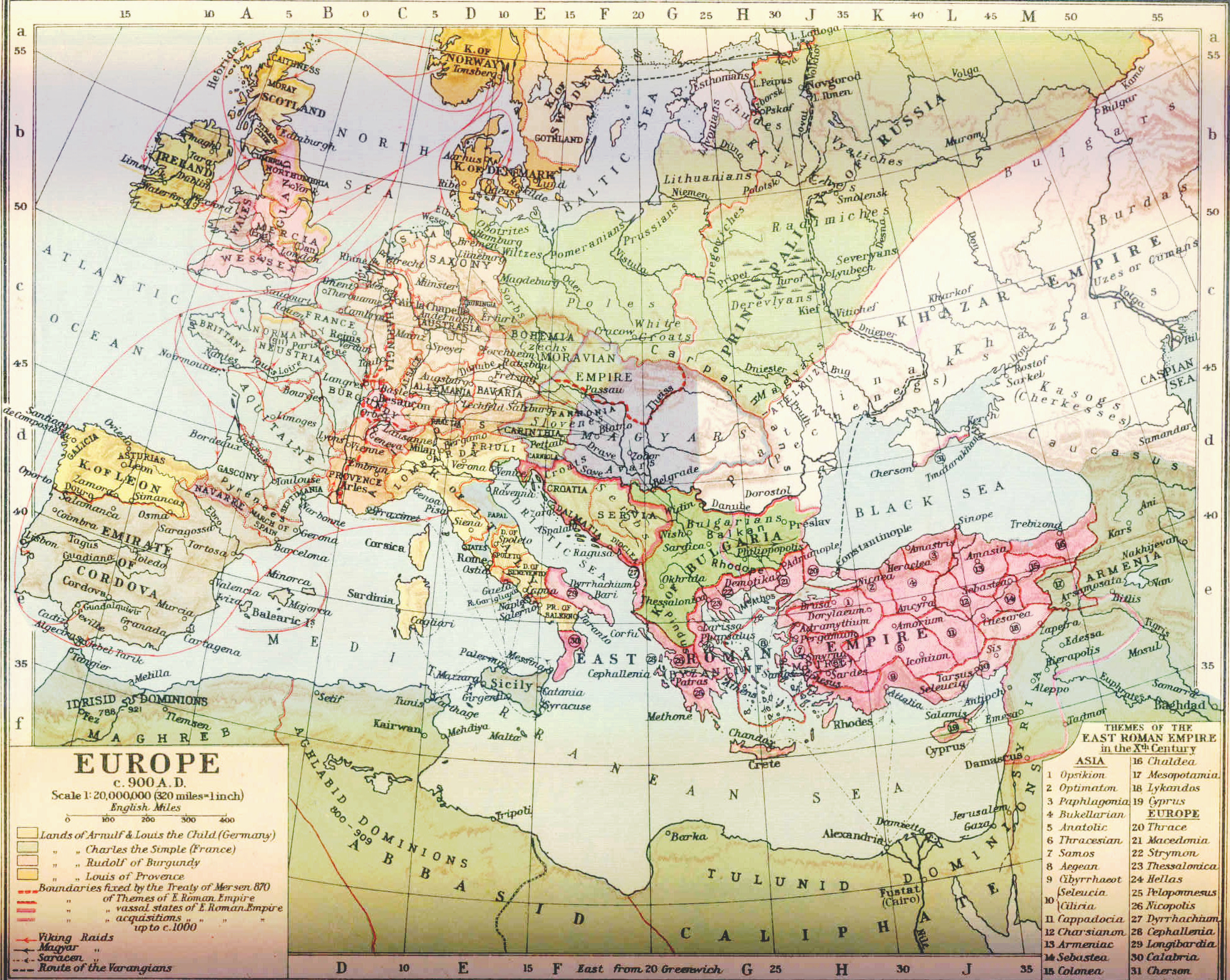

Historians essentially agree that, independent of its national and ideological perspective, the Hungarians’ conquest of the Carpathian basin was a decisive factor in the development of medieval Europe. Nonetheless, what Hungarians hail as the heroic deeds of their victorious ancestors remains to this day—in the eyes of Germans, Slavs and Romanians—a “tragedy”, a “disaster” and a “great misfortune”. Thus Georg Stadtmüller describes the Magyar invasion as a catastrophe: “The Magyars conclusively annihilated the supremacy of the German Empire in the Danube Basin, destroyed German colonisation in western Hungary, and made the continuation of the splendid Bavarian south-east colonisation impossible for more than a century and a half.”6 Some Hungarian historians, e.g. Szabolcs de Vajay in his controversial work Entry of the Hungarian Tribal Alliance into European History, claim that the early Hungarians fulfilled a double function: on the one hand as a bulwark in the Carpathian basin against the early “drive towards the east of the German empire”, and on the other as having contributed greatly, through the conclusion in 926 of a nine-year armistice, to the unity of the Germans, who were able to come to an understanding among themselves only in the face of a common danger.

The split in the Slavic world due to the Conquest proved even more significant for European history. By their settlement of the Danube basin the Hungarians drove a permanent wedge between the northern and southern Slavs. At the end of the nineteenth century the eminent Czech historian František Palacký concluded bitterly: “The invasion and settlement of the Hungarian nation in Hungary belong to the most important facts of history as a whole: in all the course of centuries the Slav world has never been struck a more disastrous blow.” In Palacký’s eyes the Hungarians appear to have inflicted as much misery on the Czechs as the Germans have. In any case, as far as Czech, Slovak and Polish historians and the schoolbooks written by them or under their supervision are concerned, the enduring fissure of the Slav people is by far the most serious outcome of the Conquest and the evolution of the Hungarian state.

The deep-seated resentments between Hungarians on one side and Czechs and, above all, Slovaks on the other are therefore rooted in early history, and have been implanted into the consciousness of succeeding generations on both sides through their legends and attitudes. Thus the Czechs and Slovaks contend that the occupying Hungarians were actually overwhelmingly Slavs, and that even the founders of the state, Árpád and St Stephen, belonged to the Slav people. As for the rumours still rife at the time of the Chief-Prince Géza about “two Hungarys”, one “white” and the other “black”, the inhabitants of the so-called “white” part (western and central Hungary) are claimed by Slovaks to have been Slavs; however, the Kabars and Pechenegs—Turkic tribes who followed the migration of the Magyars—are said to have lived in “black” Hungary as well as the tribe of the Székelys, whose origin has never been clarified.

The Hungarians, for their part, have given the impression in some legends and in the resulting epics and works of art that the inhabitants of the Carpathian basin received the conquerors under Prince Árpád with undiluted enthusiasm. This image is conveyed above all by the monumental painting by Mihály Munkácsy, “Hungarian Conquest”, which adorns the great hall of the Budapest Parliament used mainly for receiving foreign dignitaries. The canvas shows Árpád mounted regally on his white charger with his mounted retinue at the moment of his triumphal arrival in the new homeland. The inhabitants, mostly on foot, cheer their new ruler and offer him gifts. The white horse is an important element in Hungarian legend. Prince Árpád defeats Svatopluk in battle, but before it happens he commands the Prince of Moravia to surrender: Árpád sends him a white horse as a gift, demanding in return earth, grass and water—a symbol for the ancient Scythians of voluntary surrender. The legend tells us that after Árpád’s demands had been satisfied, he took all the land into his possession with confidence and an easy conscience. These rites were an established part of agreements and contracts between nomadic tribes.

We learn from a letter written to the Pope by Bishop Theotmar of Salzburg in the year 900 about mutual recriminations between Bavarians and Moravians for having concluded a treaty with the Hungarians according to pagan customs, swearing on a wolf and a dog as totems. Theotmar was killed on 4 July 907 in a large-scale battle fought by the Bavarians, who had hoped thereby to reconquer Pannonia. This attack ended with a shattering defeat at Pozsony (Bratislava) and the death of the Margrave Luitpold and a large number of the Bavarian nobility. The legend of the white horse was further embellished by a fabricated account of the death of Svatopluk, who is supposed to have drowned in the Danube during his flight from the victorious Magyars. In fact Svatopluk had entered into a pact with the Hungarians in accordance with nomadic custom to seal a joint action against the Bavarians (894), and not in an agreement to relinquish his land; the annihilation of the short-lived state occurred only after his death.

The Battle

As the final military maneuver of the Hungarian land-taking (German Landnahme) process that began in 894, the Hungarians won a decisive victory over Bavarian troops at Brezalauspurch (modern Bratislava/Pozsony/Pressburg in Slovakia: others situate the battle at Mosaburg/Zalavar in Hungary). Contemporary sources provide few details, except that the mobilization began around 17 June 907 at the river Enns, where King Louis the Child fell behind until the final defeat around 4-6 July, as testified by the entries in church necrologies, which mention Luitpold, Duke of Bavaria; Thcotmar, Archbishop of Salzburg; and Zacharias and Odo, bishops of Freising and Brixen, respectively. It was Aventinus (Johannes Turmair, 1477-1534) who reconstructed the battle on the basis of necrologies (since then partly lost), annals, and the chronicles of Rcgino of Priim and Liutprand of Cremona. He suggested an advance in three columns (on both sides of the Danube, and by ships with supplies), very similar to Charlemagne’s campaign against the Avars in 791. The columns were supposed to have had a final meeting point at present-day Bratislava, but because of some coordination mistakes they were annihilated column by column in a series of clashes over at least three days. Aventinus adds a long list of participants, mostly killed, their names recorded only in his text. Modern scholars are highly critical of his story, although it does fit very well with the geographical conditions and the light cavalry military tactics of the Hungarians. It is certain, however, that the Bavarians did give up the former Carolingian march of Pannonia forever, lost their territories east of the river Knns, and accepted the Hungarian conquests in the Carpathian Basin.

Hungarian Raids

The events of the Conquest (German: Landnahme) of the Carpathian Basin and those of the raids have been interwoven in Western historiography, because the Hungarians entered the area with raiding troops invited cither by the East Frankish court (862, 892) or their Moravian opponents (881, 894). In a broader sense the beginning of the raids goes back to the middle of the ninth century, but in a strict sense the classical raids took place during the final years of the Landnahme. 896/899 to 970. After the defeat in the battle on the Lechfeld (955), the Hungarians stopped the raids toward the west, and. as a consequence of their defeat at Arcadiopolis (huleburgaz) by the Byzantines, stopped raiding toward the southeast as well. Their approximately forty western raids are thoroughly recorded by Latin sources. Their advance to Byzantium and the east is less well known; they are believed to have made about ten attempts, although the number could have been much higher.

The classical age of the raids begins with an attack against northern Italy in 899-900, on the “invitation” of King Arnulf. Returning from their victory at the river Brenta (24 September 899), they occupied Transdanubia, the former Pannonian duchy of the Franks. Until 902/906 they also occupied the duchy of the Moravians, and later consolidated their power at the battle of Bratislava (907).

After 906 they regularly raided the German territories (Saxony. Bavaria, Thuringia, Swabia), distant areas of the west (Burgundy, the Atlantic and Danish littoral, southern France, Italy), and even Iberia in 942. The Italian, German, and Byzantine courts paid high tribute to them for decades. The most successful in defense were the Germans who. after minor victories and military and political reforms, finally crushed them in 955.

The raiding armies could be regarded as professional auxiliary troops hired by foreign dukes and kings to press their adversaries politically and militarily; the logistical problems of the raids could not have been solved without their active cooperation. The Hungarians preferred densely settled territories, such as Italy. This is proved by the fact that the coins found in graves originate mostly from Italy (67 percent) and France (21 percent), with a few from Germany (7 percent). Concerning the inner structure of the raids, very little is known; they moved in small contingents and, even united for a large battle, could exceed no more than a few thousand, despite being overestimated in the tens of thousands in contemporary sources. They regularly used reconnaissance; communicated during the maneuvers with the help of fire, smoke, and horn signals; and terrified their opponents with “diabolic” war cries of “hui, hui” Their numbers seemed much higher because of their reserve horses and the speed and rotating movements of their battle tactics. Their feigned retreat tactics are often described in battles, and strategically on a larger scale as well.

Their most respected weapon was the nomadic composite bow, having a maximum range of 492 to 656 feet (150 to 200 meters) (effective for aimed shots at 197 to 230 feet [60 to 70 meters]), with twelve to fifteen arrows loosed per minute, creating a terrifying shower of whizzing arrows and disintegrating the opponent’s battle order. They had to be resupplied with arrows several times during the fight, because the quivers contained no more than fifteen or twenty; their forces always had to possess a supply of several thousands. They were also masters of the saber, one of which is still displayed in Vienna as the saber of Attila.

The raids started mostly in spring, when their horses were fresh, but in some cases they began in late autumn or winter, suggesting that they could feed the horses without pasture. The physical abilities of their horses were well known; they were used not only in battles, but as a means of transport over the whole continent. It is still debated whether the Carpathian Basin was large enough for breeding hundreds of thousands of horses, and whether that problem could have been a possible reason for the end of the raids.

The campaigns were led on the level of tribes, but there was certainly cooperation between them in reconnaissance and in general policymaking. The regular plunder and booty became the basis of their economic and social structure, and gave the nomadic raiding way of life an extra century of existence, as well as the chance for a gradual acculturation to the sedentary agricultural economy of their neighbors, though it is still debated how much they were nomads or seminomads by the end of the tenth century. On a political level, the success of the raids secured a more independent statehood for the Hungarian Christian kingdom than for the Bohemians and Poles facing the German empire.

Hungarian historiography (with a few dissenting voices) regarded the raids as a great achievement of Hungarian martial virtues; the Hungarian term kalan dozas lacks any pejorative connotation, as opposed to the English “raids” or German Raubziige. In Hungarian oral traditions, up to the present time, Active stories of raiders survive, such as the breaking of the Golden Gate of Constantinople, or the alleged avenging of the defeat of 955, when the Hungarian captive warlord Lei, before his execution, is said to have killed the German king with his war horn.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bóna, Istvan. Magyarok es Eurdpa a 9-10. szdzadban. Budapest: MTA TTI. 2000. Gyorfly, Gvdrgy. “Landnahme, Anseidlung und Streifziige dcr Ungarn” Acta flistorica (Budapest) 31 (1985): 231-270. Kellner. Maximilian Georg. Die UngarneinfaUeirn Bildder Quellen bis 1150. Munich: Ungarisches Institut, 1997. Kristo, Gvula. Levedi tdrzsszovetsegetdl Szent Istvan dllamdig. Budapest: Magveto. 1980. Toth. Sandor Laszlo. “Les incursions des Magyars et Europe.” In Les Ilongrois et lEurope: Conquctc et integration, edited by Sandor Csernus and Klara Korompay. pp. 201-222. Szeged. Hungary, and Paris: University dc Szeged, 1999. Vajav. Szabolcs de. Dcr Eintritt des Ungarischcn Stammebundes in die Europaischc Geschichte, 862-933. Mainz, Germany: Hase & Koehler, 1968