Prelude: The Battles of Steinau and Alte Veste

Wallenstein had brought the imperial army back up to about 65,000 men. He advanced from Znaim into Bohemia with nearly half that number at the end of April. Saxon resistance collapsed. The Saxons and Bohemian exiles had thoroughly alienated the Bohemians by their plundering so that even the Protestants were glad to see them re-cross the mountains in mid-June. Wallenstein decided against invading Saxony. Leaving troops to guard Bohemia and Silesia, he headed west to join Maximilian at Eger on 1 July. Both men made an effort to get along. Maximilian was careful to address Wallenstein as duke of Mecklenburg, and loaned him 300,000 fl. for provisions.

Gustavus had left Johann Georg to fight alone. He knew the elector was still negotiating with Wallenstein and feared he might defect. He headed northwards, entrenching at Nuremberg on 16 June when he learned imperial detachments were already moving to intercept him. It would have been safer to have marched north-west to Würzburg to be closer to his other armies in Lower Saxony and the Rhineland, but Gustavus could not afford to lose a prominent Protestant city like Nuremberg. Six thousand peasants were conscripted to dig a huge ditch around the city and emplace 300 cannon borrowed from the city’s arsenal. The cavalry were left outside to maintain communications while Gustavus waited for his other armies to join him.

Having arrived on 17 July, Wallenstein resolved not to repeat Tilly’s mistake at Werben and to starve the Swedes out rather than attacking their entrenchments. He built his own camp west of the city at Zirndorf that was 16km in circumference and entailed felling 13,000 trees and shifting the equivalent of 21,000 modern truck-loads of earth. Imperial garrisons in Fürth, Forchheim and other towns commanded the roads into Nuremberg, while cavalry patrolled the countryside. Gustavus was trapped. He had 18,000 soldiers, but faced insurmountable supply problems as the city’s 40,000 inhabitants had been joined by 100,000 refugees. The Imperialists burned all the mills outside the Swedish entrenchments and the defenders were soon on half rations.

The situation was initially much better in Wallenstein’s camp because it received supplies from as far away as Bohemia and Austria. Things worsened with the hotter weather in August though. The concentration of 55,000 troops and around 50,000 camp followers produced at least four tonnes of human excrement daily, in addition to the waste from the 45,000 cavalry and baggage horses. The camp was swarming with rats and flies, spreading disease. Wallenstein had become a victim of his own strategy and by mid-August his army was no longer fully operational after the Swedes captured a supply convoy. He was unable to intercept a relief force of 24,000 men and 3,000 supply wagons sent by Oxenstierna to join Gustavus.

As tension mounted in Franconia, Johann Georg tried to improve his bargaining position by sending Arnim to invade Silesia. The hagiography surrounding Gustavus has overshadowed these events that involved significant numbers of troops and are very revealing about tension within Sweden’s alliance. Arnim had 12,000 Saxons, plus 3,000 Brandenburgers and 7,000 Swedes. The latter were under the command of Jacob Duwall, born MacDougall in Scotland, who had served Sweden since 1607 and raised two German regiments that formed the bulk of his corps, and whose presence was to ensure Arnim remained loyal. Duwall was a man of considerable energy, but like many professional officers he had become an alcoholic.

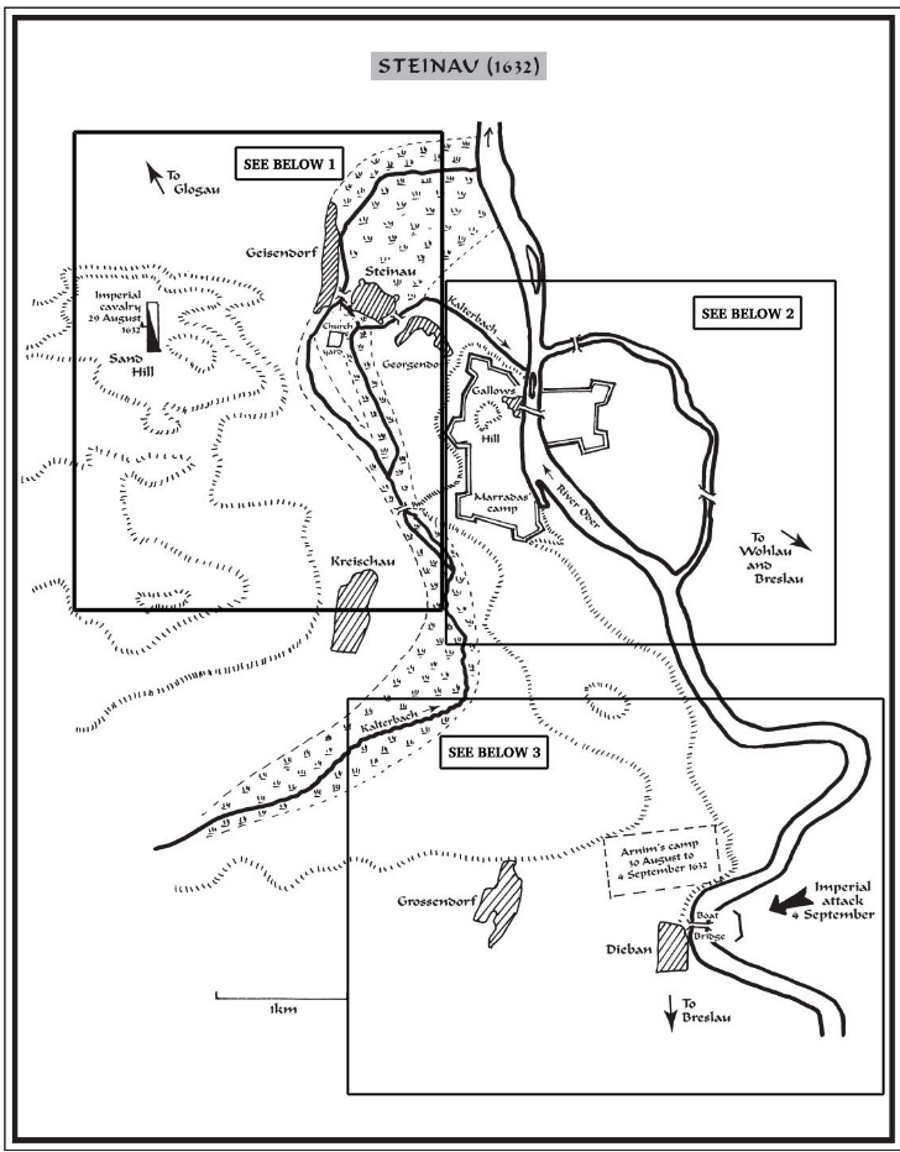

Imperial reinforcements were rushed from Bohemia to join the Silesian garrisons under the elderly Marradas, who collected 20,000 men at Steinau, an important Oder crossing between Glogau and Breslau. He entrenched on the Gallows Hill, south-east of Steinau, between it and the river, and posted cavalry on the Sand Hill west of the town to watch the approach. Musketeers occupied the Geisendorf suburb to the west and a nearby churchyard. The advance guard under the firebrand Duwall arrived at midday on 29 August, and immediately engaged the imperial cavalry. After two hours of skirmishing the Imperialists retreated into the marshy Kalterbach valley south of Steinau. Saxon artillery had now arrived on the Sand Hill and compelled the cavalry to retreat further into Marradas’s camp, exposing the musketeers. Duwall’s younger brother led 1,000 Swedish and Brandenburg musketeers who stormed the suburb and churchyard. The Imperialists set the town on fire to forestall further attack, virtually destroying it. Duwall wanted to press on, but Arnim refused. The two were barely on speaking terms and Duwall was convinced Arnim was still negotiating with the enemy on the Gallows Hill.

Rather than assault the camp the next day, Arnim marched south to Dieban further upstream where he built a bridge, intending to cross and cut Marradas off from the other side. Marradas belatedly attacked Dieban, but was repulsed on 4 September and retreated, having left a small detachment at the Steinau bridge to delay pursuit. The allied losses were slight, but the Imperialists lost 6,000, mainly prisoners or men who fled during the initial engagement. The losses indicate the continued poor condition of parts of the imperial army, especially when irresolutely led. Arnim pressed on, taking Breslau and Schweidnitz where he reversed the re-Catholicization measures. The Imperialists were driven into the mountains. Arnim had conquered Silesia with fewer troops and against greater odds than Frederick II of Prussia’s celebrated invasion in 1740.

Wallenstein decided to punish Saxony, and ordered Holk with 10,000 men from Forchheim to invade the Vogtland that formed the south-western tip of Johann Georg’s territory. As Holk began systematic plundering to intimidate the elector, the pressure mounted on Gustavus to break out of Nuremberg. The reinforcements sent by Oxenstierna arrived on 27 August, giving him the largest army he ever commanded: 28,000 infantry, 17,000 cavalry and 175 field guns. Disease and Holk’s detachment had reduced Wallenstein’s force to 31,000 foot and 12,000 horse. The odds were still not in Gustavus’s favour, especially considering Wallenstein was entrenched on high ground above the Rednitz river over 6km from Gustavus’s camp. The river prevented attack from the east, while the more open southern and western sides were furthest from Gustavus and would be difficult to reach without exposing his flank. This left the north, held by Liga units under Aldringen, and which was the strongest, highest side. The entrenchments were covered by abatis, the seventeenth-century equivalent of First World War barbed-wire entanglements made by felling and trimming trees to leave only sharpened branches pointing towards the enemy. The ruined castle that gave the position its name (Alte Veste) provided an additional strong point.

Surprise was impossible. Gustavus’s intentions were clear once he seized Fürth to cross the Rednitz on the night of 1–2 September. There is some indication that Gustavus only attacked because he thought Wallenstein was withdrawing, but this was probably put about just to excuse the debacle. The king planned to pin Wallenstein with artillery fire from east of the Rednitz, while he and Wilhelm of Weimar attacked Aldringen, and Bernhard of Weimar worked his way round to hit the weaker western side. A preliminary bombardment failed to silence the imperial artillery. Gustavus pressed on regardless, sending his infantry up the wooded northern slope early on 3 September. Thin drizzle had already made the ground slippery, and it proved impossible to bring up the regimental guns as the rain grew heavier during the day. The assault was renewed repeatedly into the night, but only gained a few imperial outworks on the western side. Gustavus gave up. He retreated covered by his cavalry, having lost at least 1,000 killed and 1,400 badly wounded. General Banér’s wounds left him incapacitated for the rest of the year. Worse, demoralization prompted 11,000 men to desert. Altogether, at least 29,000 people died in Gustavus’s camp during the prolonged stand-off, while animal casualties left only 4,000 of his cavalry mounted by the end.

Unable to remain in Nuremberg, Gustavus pulled out on 15 September. He waited a week at Windsheim to the west, before deciding that Wallenstein no longer posed an immediate threat and marching south, intending to winter in Swabia. Wallenstein had lost less than 1,000 men, but his army was sick. So many horses had died that 1,000 wagons of supplies were abandoned when he burned his camp on 21 September. He moved north, overrunning the rest of Franconia and into Thuringia, while Gallas marched through north-east Bohemia to reinforce Holk’s raiders putting pressure on Saxony. The Imperialists occupied Meissen and despatched Croats towards Dresden with the message that Johann Georg would no longer need candles for his banquets as the Imperialists would now provide light by burning Saxony’s villages.

Maximilian and Wallenstein parted ways at Coburg in mid-October. The elector agreed that Pappenheim and the Liga field force would join Wallenstein from Westphalia in return for Aldringen and fourteen imperial regiments being assigned to stiffen the Bavarians. The arrangement proved unsatisfactory, and the resulting acrimony revealed the continued tension between Maximilian and the emperor. Wallenstein complained that Pappenheim did not arrive fast enough, and indeed repeated orders had to be sent before that general finally gave up his independent role and marched to Saxony. Maximilian resented Aldringen for still reporting to Wallenstein, who already recalled some of the regiments by late November. Maximilian returned south to protect Bavaria, while Wallenstein marched north-east into Saxony, ordering the plundering to stop as he now intended to winter in the electorate.

Battle of Lützen

Gustavus realized his mistake. Wallenstein was not only threatening his principal ally, but endangering communications with the Baltic bridgehead. Against Oxenstierna’s advice, he raced north, covering 650km in 17 days at the cost of 4,000 horses. En route he passed Maximilian heading in the opposite direction. The armies were only 25km apart, but unaware of each other’s presence. The main Saxon army was still with Arnim in Silesia. Johann Georg had only 4,000 men, plus 2,000 Lüneburgers under Duke Georg who shadowed Pappenheim through Lower Saxony. Leipzig surrendered a second time to the Imperialists and its commandant was executed by the furious elector, who then made his widow pay the cost of the court martial.

Pappenheim joined Wallenstein on 7 November, while the Saxons retreated into Torgau and Gustavus rested at Erfurt after his long march. It was now very cold. Wallenstein dispersed his troops to find food, sending Colonel Hatzfeldt with 2,500 men to watch Torgau. Pappenheim was restless, wanting to return to Westphalia where the Swedes were known to be picking off his garrisons. Sick with gout, Wallenstein lacked the energy to argue, and let him go with 5,800 men. Gallas was summoned from the Bohemian frontier to replace him, but it would be some time before he arrived.

Gustavus had moved east down the Saale, taking Naumburg on 10 November. He decided to force a battle, hoping for another Breitenfeld to restore his reputation, dented by Alte Veste. As he approached the Imperialists, he learned from peasants how weak Wallenstein was and pressed on to catch him. General Rodolfo Colloredo, commanding a detachment of 500 dragoons and Croats, blocked him at the marshy Rippach stream east of Weissenfels, delaying him for four hours on 15 November. It was now too late for battle, and Gustavus was forced to camp for the night.

Wallenstein abandoned his retreat to Leipzig when he received word from Colloredo, halting at Lützen still 20km short of his destination. He had only 8,550 foot, 3,800 horse and 20 heavy guns. His right was protected by the marshy Mühlgraben stream. The Weissenfels–Leipzig highway crossed this at Lützen, a town that comprised 300 houses and an old castle surrounded by a wall. Wallenstein guessed correctly that Gustavus would not attempt another frontal assault, but would cross further south-east to outflank him. Accordingly, he drew up just north east of the town parallel to the road. Musketeers spent the night widening the ditches either side of the road, while Holk supervised deployment of the main army, lighting candles to guide units into position. Four hundred musketeers were posted in Lützen to secure the right, and thirteen guns were placed on the slight rise of Windmill Hill just north of the town. Around half the cavalry drew up behind with the rest on the left. The infantry deployed in between in two lines, with another 7 guns on their left and 420 musketeers lining the ditches in front. There were not enough cavalry to cover the gap from the left to the Flossgraben ditch that cut the highway beyond Wallenstein’s position. Isolano’s 600 Croats were posted as a screen across the gap with the camp followers and baggage massed in the rear holding sheets as flags to create the impression of powerful forces behind. They were supposed to wait until Pappenheim, recalled during the night, could replace them.

Johann Georg refused to send reinforcements from Torgau, but Gustavus had nearly 13,000 infantry, 6,200 cavalry and 20 heavy guns and so remained confident. His army assembled in thick fog about 3,000 metres to the west early on 16 November to hear the king’s stirring address. As Wallenstein predicted, Gustavus swung east across the Mühlgraben and then north over the Flossgraben to deploy around 10 a.m. in front of him. The action began as the fog lifted around an hour later and the Swedes made a general advance towards the imperial positions. Gustavus used his customary deployment in two lines, with the cavalry on the flanks stiffened with musketeer detachments. The best infantry were in the first line, while the king commanded most of the Swedish and Finnish horse on the right and Bernhard of Weimar led the 3,000 mainly German troopers on the left.

The Croats soon scattered, prompting the decoy troops to take to their heels. Gustavus was nonetheless delayed by the musketeers hidden in the ditch. Widely cited reports that Wallenstein spent the day carried in a litter stem from Swedish propaganda. Despite pain from gout, he mounted his horse to conduct an energetic defence. Lützen was set on fire to stop the Swedes entering and turning his flank. The wind blew the smoke into his enemies’ faces and, as at Breitenfeld, it quickly became impossible to see what was happening. Bernhard’s men were unable to take either Lützen or Windmill Hill. The real chance lay on the other flank where Gustavus had more space to go round the end of the imperial line. Wallenstein switched cavalry from his right to stem the king’s advance.

Pappenheim arrived in the early afternoon with 2,300 cavalry, having ridden 35km through the night. His arrival encouraged the Croats to return and together they drove the Swedes back across the road. The veteran Swedish infantry also suffered heavy casualties and fell back, having failed to dislodge the imperial centre. Wilhelm of Weimar’s bodyguard fled, panicking the Swedish baggage which also took off. Several imperial units had also broken, and both armies were losing cohesion. Pappenheim had been shot dead early in his attack; Wallenstein’s order summoning him was later retrieved bloodstained from his body. The battle disintegrated into isolated attacks by individual units.

Gustavus appears to have got lost as he rode to rally his shattered infantry and was shot, probably by an imperial infantry corporal. His entourage tried to lead him to safety, but blundered into the confused cavalry mêlée still in progress amid the smoke on the right where he was shot again, by Lieutenant Moritz Falkenberg, a Catholic relation of the defender of Magdeburg, who himself was then slain by the Swedish master of horse. The fatal shot burned the face of Franz Albrecht of Lauenburg who was accompanying the king as a volunteer. Under attack himself, Franz Albrecht could no longer support the king in his saddle and he fell dead to the ground. The Swedes never forgave the duke for abandoning their monarch’s body, which was subsequently stabbed and stripped by looters. Rumours of the king’s death added to the growing despondency in the Swedish ranks. Knyphausen, commanding the infantry, insisted Gustavus was only wounded and the royal chaplain, Jacob Fabricius, organized psalm singing to boost morale. Unaware of what had happened, Bernhard continued his fruitless attacks on Lützen.

The fighting subsided around 3 p.m. Knyphausen advised retreat, but Bernhard, now appraised of the situation, urged another assault that finally carried Windmill Hill. Firing ceased two hours later, after dark. Pappenheim’s 3,000 infantry arrived an hour after that. Wallenstein was exhausted and appalled at the loss of at least 3,000 dead and wounded, including many senior officers. He decided to retreat and abandoned his artillery and another 1,160 wounded, who were left behind in Leipzig as he fell back into Bohemia. The Swedes lost 6,000 and were on the point of retreating themselves when a prisoner revealed that the Imperialists had already gone.

The disparity of the losses, magnified by Gustavus’s presence among the Swedish dead, fuelled the controversy over who really won. Protestant propaganda and Gustavus’s firm place on later staff college curricula have ensured that Lützen is generally hailed as ‘a great Swedish victory’. Wallenstein showed far superior generalship, whereas Gustavus relied on an unimaginative frontal assault with superior numbers. The Swedes were able to claim victory because Wallenstein lost his nerve and retreated, not least because he was not certain until 25 November that Gustavus was dead. Wallenstein probably regretted this mistake. He certainly vented his fury on the units that had fled in the battle, insisting on executing eleven men, but he also distributed bonuses to the wounded and richly rewarded those who distinguished themselves like Holk and Piccolomini.

Lützen’s real significance lay in Gustavus’s death. The Swedes continued fighting, already helping the Saxons evict the remaining Imperialists from the electorate by January. But their purpose had changed and Oxenstierna sought, albeit with little success, to extricate his country under the best possible terms.