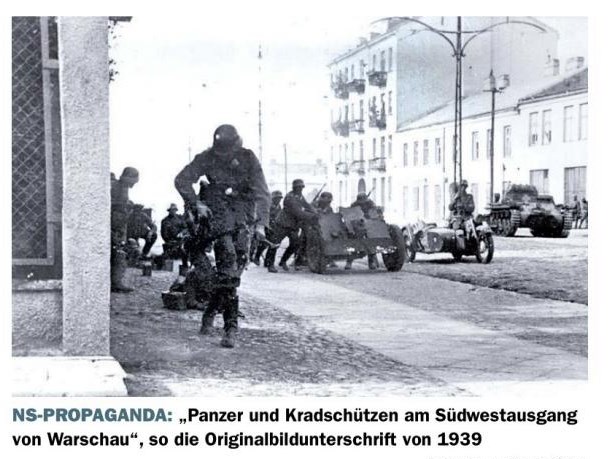

On September 8, 1939, one week into the Nazi invasion of Poland, German armoured troops reached the gates of Warsaw. The Polish government and High Command had left the city but a determined garrison awaited the enemy invader and the Poles were able to stave off two consecutive German attempts to take the capital by armoured attack. Thus began a siege that would last for three weeks and subject the Warsaw Army of over 100,000 and the civilian population of over one million to a ruthless campaign of aerial bombardment and heavy artillery shelling, causing thousands of casualties and widespread destruction. It was a hopeless battle that could only end in defeat and on September 27 the Polish garrison capitulated. The photos of the first penetration by tanks and infantry of the 4. Panzer-Division taken on September 9 became standard repertoire of German propaganda publications on the Blitzkrieg in Poland.

Map of initial ground attacks on Warsaw. Poles-blue, Germans-red.

Pz II Ausf C of 4th Panzer Division, destroyed by Polish troops at Grójecka St. Warsaw 1939.

The advance of 4th Panzer Division was no less relentless, no less exhilarating that Friday. The panzers passed through burning villages and destroyed bridges, leaving Polish stragglers behind in the copses and forests. And everywhere, the remnants of a defeated opponent. ‘Panic must have broken out among the enemy,’ Willi Reibig concluded. ‘Each man looked to save himself in a wild flight. Were they so filled with fear in the face of our panzers? All the better then if they’re already shaken morally, we’ll have easier battles. Bits of equipment, field kitchens, baggage wagons, cases of ammunition, guns, rifles and ammunition lined our route of advance in large quantities. Between them, bomb craters on the left and right of the road.’ Another road sign. Warszawa 70 kilometres. ‘We’ll soon achieve that,’ Reibig was convinced. Tenth Army commander von Reichenau now decided it was time ‘to pluck the enemy capital like a ripe fruit’ before the enemy could respond. The men of 4th Panzer Division would soon learn that Warsaw’s fruit left a bitter taste.

In his headquarters in the heart of the Polish capital, the commander of the city’s defensive zone, General Walerian Czuma ordered Warsaw be turned into a fortress. Here at the walls of the great city the ‘ravaging of Polish soil comes to an end’. In a rousing order of the day, he continued: ‘We have taken up a position, from which there can be no more steps back. The enemy can receive just one answer now: “Enough! Not one step further!”’

Warsaw’s inhabitants and troops built makeshift barriers from overturned trams, removal vans and furniture, then took up position behind them, or in cellars, or rooftops, or at the windows of tenement blocks. And then they waited for the enemy to come.

Around 5pm, the first German tanks appeared, the armour of 35th Panzer Regiment. The panzers rolled through the ‘ugly’ suburbs of Ochota – four miles from the city centre – then Rakowiec, three miles from the heart of Warsaw. ‘Everyone went into the heart of Warsaw proudly and confident of victory,’ Reinhardt recalled. Everyone went in expecting Warsaw to be an ‘open’ city – undefended. But then the defenders opened fire. Standing with a pair of binoculars at an anti-tank gun position, Colonel Marian Porwit watched as ‘an unequal duel of fire raged – so heavily in our favour that the German panzers no longer moved.’ Even so the barricades which had been hastily erected were no match for the armour’s firepower, Porwit observed. ‘They shot up in flames like matches.’ But the defenders grew in stature. ‘The first burning panzer and destroyed vehicles calm us down, and the soldiers, seeing the excellent results of their weapons and their leaders, gain trust and believe that they do not have black devils in front of them,’ one Polish officer recorded. Heinrich Eberbach, 35th Panzer Regiment’s commanding officer, ordered his armour off the main road and through allotments to avoid the barriers ‘but even there our panzers are shot at from four-storey houses, from skylights, windows and cellars, and from behind more barricades’. As the sun went down over Warsaw, Eberbach reluctantly called off his attack and returned to the road bridge where his attack had begun barely two hours earlier.

After dark, state radio broadcast Walerian Czuma’s order of the day. Lieutenant Colonel Waclaw Lipinski, head of the Polish General Staff’s information section, added his own postscript. ‘Warsaw will be defended to the last breath and – if it falls – the enemy will have to step over the corpse of the very last defender,’ he declared. Now the hour had come for Varsovians to demonstrate their love for their motherland. ‘Looking around, the Polish soldier should see only calm faces,’ the officer continued. ‘He should be accompanied by the blessings and smiles of women and when he goes into battle, a cheerful song should sound.’

Panzer grenadier Bruno Fichte spent the night quartered between a sanatorium and houses on the edge of Warsaw. Polish artillery shells rained down on the homes as smoke rose from their chimneys. ‘I went into the house,’ Fichte recalled. ‘It was full of women and children. I asked them to please go down into the cellar and not make fires any more.’ The women begged for a warm drink for their children; Fichte fetched warm milk and coffee. His actions were not entirely magnanimous; he wanted to spare the panzers the constant shelling. ‘Nevertheless, they treated me like their saviour and kissed my hands.’ Fichte and his comrades spent the night re-fuelling, stocking up on ammunition, eating, sleeping, all untroubled by the Poles. In Warsaw ‘hundreds of barricades shot up like fungi after a rainstorm’ as the garrison prepared for the enemy to renew his thrust into the capital. But to what end? schoolteacher Chaim Kaplan asked himself. ‘The streets are littered with trenches and barricades. Machine-guns have been placed on the roofs of houses and a barricade has been set up in the entrance to my apartment block, just beneath my balcony,’ he recorded in his diary. ‘If there’s fighting in the streets then there won’t be one stone standing on top of the other in the walls in which I live.’

With the first rays of light on Saturday morning, a ten-minute artillery barrage was unleashed upon the main route of advance into the city centre. And then, at 7am, the regiments of 4th Panzer Division moved off in two groups through the outskirts of Warsaw, closely followed by infantry. Bruno Fichte peered up at the tall tenement blocks looming over the narrow Warsaw streets with a sense of foreboding. But it was only when the advance was well under way that the Poles showed themselves. ‘Terrible fire descended upon us. They fired from the roofs, threw burning oil lamps, even burning beds down on to the panzers. Within a short time everything was in flames.’

In Wolska Street in the suburb of Wola, little more than one mile from the centre of the Polish capital, Colonel Marian Porwit watched as a column of panzers edged nervously along. There was a blast from a trumpet and a barrage was unleashed upon the advancing enemy. ‘German soldiers jumped out of their panzers on fire, but could find no cover in the narrow street,’ Porwit wrote. ‘Fuel tanks were set on fire. The panzers and German vehicles were on fire.’ Vehicles following behind the first panzers tried to avoid the melee, but instead ran up the pavements and blocked the road.

The city, 35th Panzer Regiment’s commander Heinrich Eberbach observed, was defending itself ‘with courage born of desperation’. A first then a second barricade was passed, but at terrible cost to man and machine. ‘The infantry must fight house by house and clear them out,’ wrote Eberbach. ‘Bursts of machine-gun fire, hand grenades from above and out of cellars, blocks of stone hurled down from the roofs, make things difficult for them.’ Inside his panzer, Willi Reibig heard machine-gun fire clatter against the armour. ‘Gun and machine-gun fire sprays out of the houses,’ Reibig recorded in his diary. ‘An infantry gun is brought to the front by a platoon, and its shells fire directly into the houses. We slowly gain ground. But around me it has already become damned hot.’ Over the headphones, there was a cry: ‘Eagle in front.’ A knocked-out panzer partially blocked the road, but not to prevent Reibig squeezing past. By now, Reibig has passed through four barricades. ‘Suddenly, a devastating blow,’ he recalled. ‘I throw up the hatch, an artillery hit on one of the panzers following us. Polish artillery lays down shot after shot on the road and in front of the barricade.’

It was, one Feldwebel – a platoon commander in 36th Panzer Regiment – observed, as if ‘all hell broke loose. In front of us one shell landed one after another rapidly.’ The Feldwebel scanned the streets through his panzer’s optics: two Panzer IIs to the rear were ablaze; a Panzer III to the side was struck by an anti-tank shell. A smoke canister exploded, shrouding the street in a grey-black mist, under which the German armour fell back; the attack had been called off. ‘We continued through dingy backyards,’ the Feldwebel continued. ‘Our panzer thundered past the corners of houses and grazed walls. Bricks clattered and scraped against our iron hull. All of a sudden, I saw a civilian who jumped out of a corner made a brief movement with his arm. A pineapple hand grenade flew towards us, without causing any damage. He didn’t get around to throwing a second one.’

One panzer got as far as Warsaw’s central station, then was forced to fall back. Heinrich Eberbach watched as panzer after panzer was shot-up, until his vehicle too fell victim to the furious Polish fire. By mid-morning, 4th Panzer’s assault on the capital had ground to a halt. Its commander, Georg-Hans Reinhardt, decided the battle was ‘hopeless’ and ‘with a heavy heart’ broke off the attack mid-morning and pulled his panzers back to the edge of the city. His division stuttered out of Warsaw under a hail of Polish artillery shells; damaged and abandoned panzers lined the main road. Exhausted crews assembled, minus their armour, at the jump-off point where the attack had begun with such high hopes five hours earlier.

A shell-shocked Heinrich Eberbach returned on foot. ‘At first the number of panzers appearing is terrifyingly low,’ he recorded. His regiment had moved off with 120 vehicles at dawn; by mid-afternoon, just fifty-seven were still combat-worthy. The panzers of brigade and regimental commanders had been knocked out, two company commanders had been killed. And yet Eberbach’s men were buoyant. ‘The combat spirit of the troops was unshaken even though the attack on the city was repulsed,’ the panzer commander reported. ‘Everyone knew that time worked for us. Their resistance cannot last long after the other divisions arrive.’

Intelligence reports suggested 4th Panzer Division had run into elements of as many as five divisions. Its commander reported in person to his immediate superior XIV Corps’ commander Gustav von Wietersheim in the small town of Nadarzyn, fifteen miles southwest of Warsaw’s centre. The picture Reinhardt painted was black: a brigade and regimental commander had come back on foot, knocked-out panzers, too few infantry, too little artillery support. The attack on Warsaw could not be carried with the means at his disposal, he told Wietersheim. And at any rate, what was the use of seizing a city ‘of little value militarily’, Reinhardt argued.

In the centre of Warsaw, Colonel Marian Porwit walked past still-smouldering panzers. The city was deserted, save for its defenders and German dead. The inhabitants were still in hiding, several hundred of them in the cellars of the Akademicki Cathedral. ‘Someone told me that fear and unease ruled there because the sound of battle had reached the shelter and asked me to say a few reassuring words,’ Porwit recalled. With the sun going down and with no sign of a renewed German assault, the officer found time to visit the cathedral. ‘A large crowd gathered around me, and when I told them of the defence against the German attack, the destroyed panzers and the enemy’s bloody losses, there was delight.’ Varsovians would enjoy a few days’ respite from the foe. For to the west of the city that very day Polish troops had unleashed an offensive. Perhaps they might save the capital. And the nation.