Since January 1943, partisan operations against the railroads in the rear of German Army Group Center had been disrupting troop and supply movements. On June 14, Stavka initiated a comprehensive “rail war” focused on the lines into the Kursk sector. Raids destroyed bridges, disabled rolling stock, and diminished train crews’ morale and effectiveness. They created traffic jams offering profitable targets to Red Air Force night bombers, who in turn were for practical purposes unopposed because night fighters, guns, and their supporting electronic systems were increasingly needed for the defense of the Reich itself.

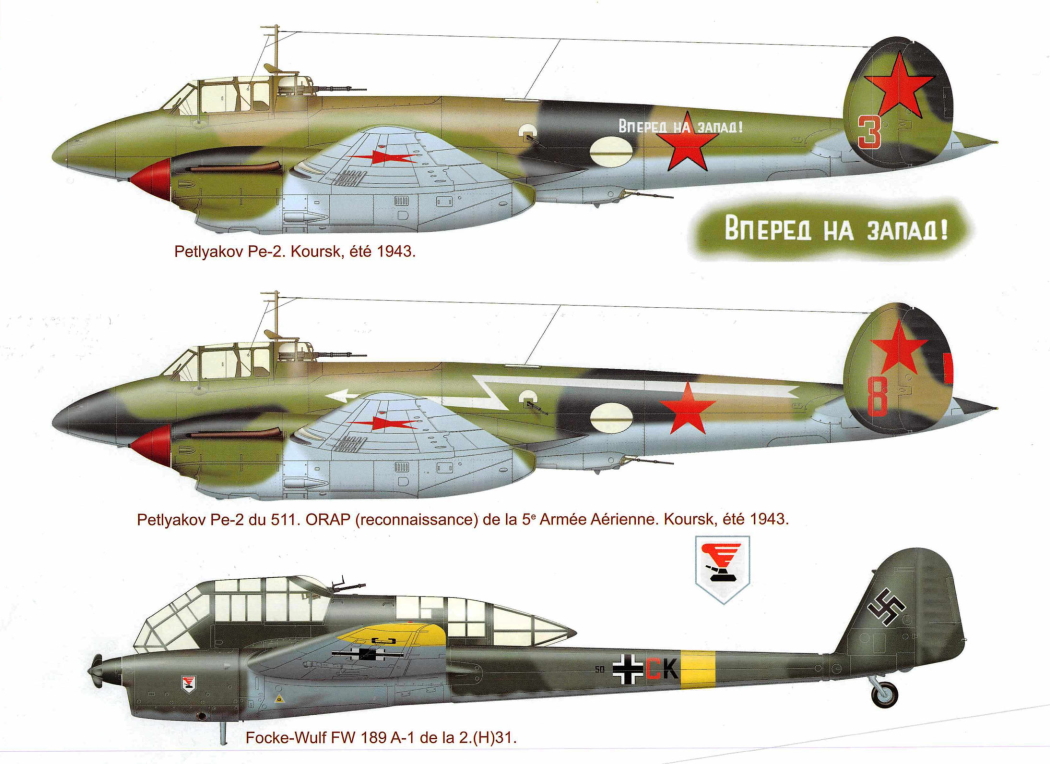

Soviet air doctrine was geared to the ground war. Close support and interdiction were its foci. In the context of Kursk, that involved a campaign against German air? elds and railroads in the salient’s immediate rear by twin-engine bombers, as many as four hundred in a single raid. These were supplemented by the night light bomber regiments, composed of single-engine Polikarpov Po-2 biplane trainers-often flown by female military aviators (dubbed “night witches”). The planes’ distinctive engine sounds won them the nickname “sewing machines” from Landser regularly awakened by their pinprick strikes.

Initially, German air offensives into Soviet rear areas were small-scale efforts, focused on train busting. These operations also diverted resources from a more relevant target: the Kursk rail yards, central to Soviet logistics in the salient. Major German raids on May 22 and June 2-3, the latter a round-the-clock operation, met bitter resistance from superior numbers of fighters. Losses were heavy enough and damage was so quickly repaired that the Luftwaffe decided to suspend daylight operations against Soviet rear areas for the balance of Citadel. Night operations continued at a nuisance level-though one midnight strike unknowingly hit Rokossovsky’s command post. He escaped by “mere chance,” or perhaps intuition. Both would be riding with the Red Army in the coming weeks.

The Soviet air force had paid a high tuition since 1941 but had learned the Luftwaffe’s lessons of centralization and flexibility. Three air armies contributed directly to the defense of Kursk: the Sixteenth and the Second, attached, respectively, to the Central and Voronezh Fronts, and the Seventeenth from the Southwestern Front. The initial numbers totaled around 1,050 fighters, 950 ground-attack planes, and 900 bombers. Stavka had also assembled an impressive reserve force of three air armies with 2,750 planes. Intended to spearhead the attack projected to follow the German defeat, they soon joined in the fighting. Finally, more than 300 bombers from Long Range Aviation and 300 fighters from Air Defense Command were assigned for night raiding and point defense, respectively.

Hauptmann (captain) Sayn-Wittgenstein was moved to the Eastern Front in February 1943 after he had been appointed Gruppenkommandeur (group commander) of the IV./Nachtjagdgeschwader 5 (IV./NJG 5—4th Squadron of the 5th Night Fighter Wing) on 1 December 1942. Here Unteroffizier Herbert Kümmritz joined Sayn-Wittgenstein’s crew as his radio and wireless operator (Bordfunker).

On the Eastern Front again with I./Nachtjagdgeschwader 100 (I./NJG 100—1st Squadron of the 100th Night Fighter Wing) on 1 August 1943. While stationed at Insterburg, East Prussia, Sayn-Wittgenstein shot down seven aircraft on one day, six of them within 47 minutes (victories 36–41), in the area north-east of Oryol on 20 July 1943, making him an “ace-in-a-day”.

Sayn-Wittgenstein claimed three more victories on 1 August 1943 (victories 44–46) and three more on the night of 3 August 1943 (victories 48–50). Sayn-Wittgenstein was credited with 83 nocturnal aerial victories, claimed in 320 combat missions, including 150 with bomber arm. His 83 aerial victories include 33 shot down on the Eastern Front.