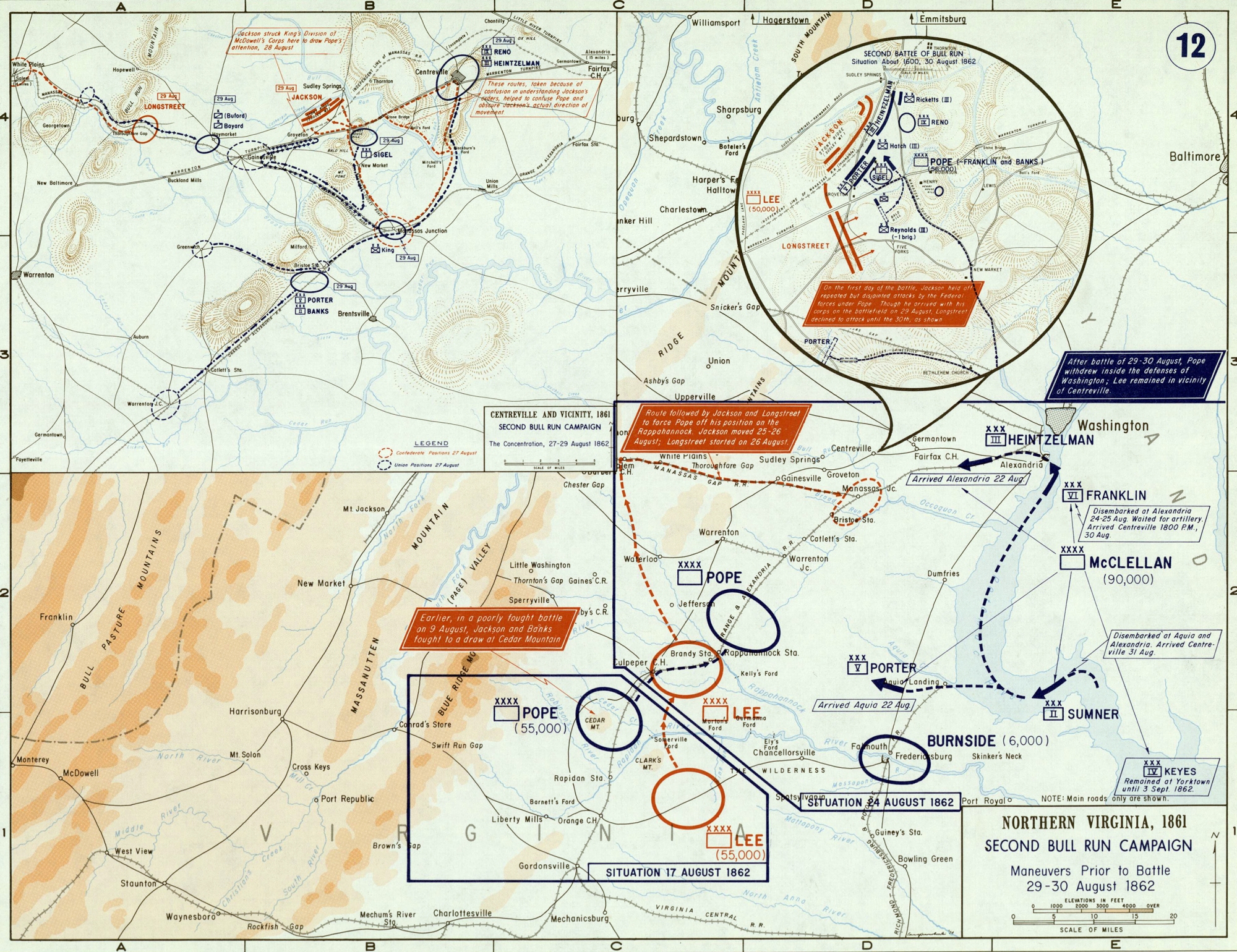

Second Bull Run Campaign, August 17–30, 1862

Fitz John Porter and his Fifth Corps were left in limbo. He realized (through several captures) that he was confronting Longstreet’s wing of the Rebel army; he was saddled with orders that now made even less sense than before; and he was told by his superior McDowell that he should stay where he was. He deployed skirmishers and posted his guns, listened to the cannonading from Pope’s front, and hoped for insight. He did not attempt to “feel” the enemy, to estimate, for his own and Pope’s benefit, what he was facing. Finally at 4:30 he sent a dispatch reporting the enemy “in strong force on this road” and his decision to fall back. At headquarters at 6 o’clock Heintzelman made note, “Gen. Porter reports the Rebels driving him back & he retiring on Manassas.”

Pope’s 4:30 courier had crossed Porter’s 4:30 courier. That Porter was retreating instead of attacking put Pope in a rage. McDowell calmed him enough that he put aside thoughts of arresting Porter, but just barely. In fact Porter attempted to act on Pope’s 4:30 order, which only reached him two hours later, at sunset. But at the front, George Morell argued it would be dark before he could mount an attack with his division; in any case, the idea of attacking here was rooted in what he politely called a misapprehension.

Pope’s next order to Porter was threatening: “Immediately upon receipt of this order . . . you will march your command to the field of battle of today and report to me in person for orders. You are to understand that you are to comply strictly with this order, and to be present on the field within three hours after its reception or after daybreak tomorrow morning.” This marked the opening gun of John Pope’s vendetta against Fitz John Porter.

By day’s end on August 29 General Pope was fully delusional about the enemy. His military instincts had proved rudimentary at best. He was unable to fathom the deadly game Lee was playing, unable to grasp that while he bent all his efforts to prevent Jackson from escaping, Jackson was in fact pinning him to the ground for a sledgehammer blow by Longstreet. Nothing of Pope’s experience in the Western theater prepared him for this, nor was he capable of recognizing the challenge, much less meeting it. His style of command emerged erratic and mistrustful. He split up the Potomac army’s Third Corps, dealing directly with Hooker and Kearny and undermining Heintzelman. He also undercut the Ninth Corps’ Jesse Reno. He commanded Porter’s Fifth Corps through McDowell (when he could be found). He matched his mistrust of Potomac army generals with mistrust of Sigel and Banks of his own army. This hardly inspired confidence among his lieutenants.

To be sure, Pope was handicapped by Irvin McDowell’s failings. McDowell never delivered Ricketts’s intelligence on Longstreet at Thoroughfare Gap, and was half a day late passing on Buford’s sighting of Longstreet’s arrival on the field. He avoided command responsibility, and (as Pope complained) was often absent. Porter saw McDowell’s motives as self-serving. Porter reported a conversation on August 29 when they received Pope’s joint order. “McClellan won’t have anything to do with this campaign,” McDowell said; “that is decided on.” He anticipated victory and expected to claim a major share of it. “I will be at the highest round of the ladder and will take care of such of McClellan’s friends as stick to me.” Porter said he made no reply.

At 5:00 a.m. on August 30 Pope sent Washington his first report since the fighting began. He spoke of “a terrific battle here yesterday,” of driving the enemy from the field “which we now occupy.” Prospects seemed bright: “The news just reaches me from the front that the enemy is retreating toward the mountains. I go forward at once to see.”

Pope drew this conclusion in part from a clash the evening before along the Warrenton Turnpike. Confederate ambulances were sighted moving westward on the pike, and John Hatch’s division was sent in pursuit. The pursuit promptly ran head-on into strong opposition and Hatch sent back for help. McDowell was disbelieving: “Tell him the enemy is in full retreat and to pursue him!” Darkness ended thoughts of pursuit, but not delusions of retreat.

Daylight brought other sketchy reports of an enemy withdrawal. At the front Rebels were overheard talking of pulling back. Enemy troops sighted rearranging their lines were assumed to be heading away. At a council of corps commanders—McDowell, Sigel, Porter, Heintzelman—Pope proposed to strike at Jackson’s left, where Kearny had battled, with the corps of Heintzelman, McDowell, and Porter. The high command’s conclusions that August 30 morning were summed up in Heintzelman’s diary: “McDowell and I went & reconnoitered & were of the impression that the enemy were not in force on their left. We met Sigel as we returned & he holds the center & he was of the impression they had left. When we got to Pope . . . he reported the enemy had been moving off towards our left & Thoroughfare Gap all night.”

Pope’s conviction of an enemy retreating was not shaken by witnesses describing quite the opposite. Porter, in a tense interview, said it had to be Longstreet on and west of the Manassas–Gainesville road. Pope, said Porter, “put no confidence in what I said.” Nor did Pope give credence to John Reynolds’s claim of Longstreet’s presence. Generals James Ricketts, Isaac Stevens, and Marsena Patrick testified to enemy sightings at the front. Patrick said the Rebels were as numerous north of the turnpike as they were the day before. “You are mistaken,” Pope told him. “There is nobody in there of any consequence. They are merely stragglers.” Such was the confidence at headquarters, Washington Roebling reported, that two of Pope’s staff, “who were a little sprung, got up a party to go out on the battle field and count the dead rebs.”

Pope’s morning idea of striking Jackson’s left with three army corps faded away. David Strother watched Pope pacing, “smoking as usual, evidently solving some problem of contradictory evidence in his mind. His preconceived opinions and his wishes decided him. McDowell came in and they spent the morning under a tree waiting for the enemy to retreat.”

What agitated Pope’s thoughts that morning was what to do about this retreating enemy. Should he promptly pursue, however disorganized or suspect his generals? Should he pause to refit and revictual, mesh the two armies, and make a fresh start? That would be the prudent course. But that would be to admit the Rebels had gotten the best of him, had run rings around him. That, John Pope in his pride would not admit. So at noon on August 30 Pope ordered that his forces “be immediately thrown forward and in pursuit of the enemy, and press him vigorously. . . .” Leading the charge would be Fitz John Porter’s Fifth Corps, which in Pope’s eyes had so far contributed nothing to the campaign.

The Fifth Corps was shorthanded, for George Morell, along with Charles Griffin’s brigade, had gotten lost trying to rejoin the army. Still, Porter’s offensive promised to be the largest Federal effort yet—his two Fifth Corps divisions, plus John Hatch’s division from McDowell’s corps, some 10,000 men. Dan Butterfield replaced the absent Morell. The initial assault wave had three first-time brigade leaders, Colonels Henry Weeks, Charles W. Roberts, and Timothy Sullivan. In support were Sykes’s regulars. At 3 o’clock, wrote Major George Hooper, 1st Michigan, “Gen Butterfield rode up to the rear of our line, called for our cheers, and gave the command to charge, and we swept out of the forest like an avalanche.”

Pope’s instructions called for Porter to pursue along the axis of the Warrenton Turnpike, but Porter recognized the folly in that and struck instead at the Rebels behind the railroad embankment north of the turnpike in the hope of at least starting a retreat. The approach was intimidating—mostly open ground and under the fire of two battalions of artillery at the hinge between Jackson’s and Longstreet’s lines, posted to deliver deadly enfilade fire. These batteries, wrote Major Hooper, “followed our every movement in this charge, in a way I have never seen equaled before or since . . . and here the slaughter commenced.”

Colonel Sullivan’s brigade on the right had the best cover and was farthest from the murderous Confederate artillery and got right up to the railroad embankment, but no farther, huddling there and looking for reinforcement. General Hatch fell wounded. Roberts’s brigade, at the center, and Weeks’s, on the left, took fearful losses in the open ground before settling into their own firefight at the embankment. In his inexperience Weeks led his troops into the open in column, easy targets for the enemy guns as they deployed. “From behind this embankment,” Marsena Patrick wrote, “a continuous discharge of Musketry was kept up, which it was impossible to return as the enemy was perfectly protected.” Nowhere could they breach the Rebel line. “In this position we remained upward of thirty minutes,” Colonel Roberts reported, “our brave boys holding their ground, but falling in scores.”

Pope initiated no diversions in support of Porter’s assault, and the Union artillery, scattered and lacking central direction, was unsupportive. With his lead brigades stymied and with the enemy guns completely dominating the ground over which reinforcements would advance, Porter aborted a mission he had considered pointless from the start. The rest of the Fifth Corps and Hatch’s brigades stood down, and the advance was recalled. Running the gauntlet of enemy fire, the survivors came back in considerable disorder.

Irvin McDowell, whom Pope had put in charge of the pursuit, now seriously misread the battlefield. When the Fifth Corps was ordered away to join the rest of the army, John Reynolds’s division remained as the only sizable force on the Federal left. Watching Porter’s advance falling back in confusion, McDowell ordered Reynolds to support the supposedly weakened center. Reynolds had warned McDowell that the Rebels “were not in retreat, and their right was across the pike outflanking us.” McDowell “ridiculed the idea,” revealing himself as uncomprehending as Pope, and presently Reynolds marched across the Warrenton Pike, leaving behind open, empty fields and woods in front of James Longstreet’s legions.

At 4 o’clock Longstreet unleashed 25,000 men against the Federals’ open left flank. Just two Yankee brigades faced the wave of attackers—Gouverneur Warren’s Fifth Corps brigade guarding a battery, and on an eminence called Chinn Ridge, Nathaniel C. McLean’s brigade from Sigel’s corps. Warren’s force totaled a thousand men, and the Rebels stormed over them. As he had at Gaines’s Mill, Warren thrust himself into the fighting, managing the best retreat he could and saving the battery. A mile or so back where the survivors rallied, “Warren sat immobile on his horse, looking back at the battle as if paralyzed. . . .”

At last the scales fell from McDowell’s eyes. He tried to recall Reynolds’s Pennsylvania Reserves to their blocking position south of the turnpike, but could only commandeer Reynolds’s trailing brigade. The Confederates scattered the Pennsylvanians, capturing a battery. They next targeted Chinn Ridge and the brigade of Colonel McLean, a Cincinnati lawyer whose father, John McLean, had been a long-serving Supreme Court justice. McLean posted his four Ohio regiments and a battery and determined to at least buy some time.

McLean’s 1,200 men beat back the first assaults, and McLean watched the enemy retire “more rapidly than they had advanced.” Division commander Robert Schenck rode up to encourage the defenders, only to be wounded severely enough to retire him from field command. Presently masses of troops appeared beyond McLean’s left. He ordered a section of artillery to train on them, but countermanded “upon the assurance of someone who professed to know the fact that they were our own troops.” As happened to McDowell’s batteries at a decisive moment at First Bull Run, mistaken identity proved fatal this day to holding Chinn Ridge. “Our own troops” were in fact the enemy, and they turned McLean’s flank and wrecked his brigade. “I do not know that I was ever so angry or mortified in my life,” he remembered.

The fighting was an hour old before McDowell was able to persuade Pope that this surprise attack was the work of Longstreet, and that it put the army at grave risk. While McDowell tried to hold the Chinn Ridge line, Pope turned to the defense of Henry Hill. Should the Confederates seize this high ground overlooking the Warrenton Turnpike, they would outflank the entire Union army.

McDowell collared troops wherever he could find them—the brigades of Zealous B. Tower and John W. Stiles from Ricketts’s division, the brigades of John A. Koltes and Wladimir Krzyzanowski from Sigel’s corps—to reinforce McLean’s collapsing Chinn Ridge defense. It was futile. The Rebels assaulted the ridge from left, right, and center, killing Koltes and wounding Tower, taking a battery, sending the Federals pelting for the rear. Among the dead was Colonel Fletcher Webster, 12th Massachusetts, son of the revered Daniel Webster.

In July 1861 it had been Federals attacking and Confederates defending Henry Hill; today the roles were reversed. Pope gathered the army’s odds and ends and spare parts. There were the other two brigades of Reynolds’s Pennsylvania Reserves, under Truman Seymour and George Meade, two brigades of Sykes’s regulars, under Robert Buchanan and William Chapman, and two small independent brigades, under Robert Milroy and A. Sanders Piatt. At the same time, Pope stood up to the prospect of defeat. He had his right wing begin to disengage for a potential retreat. Orders went to Nathaniel Banks’s corps on guard at Bristoe Station to fall back on Centreville. William Franklin, whose Sixth Corps was finally released early that day by McClellan, was told to man the fortifications at Centreville “and hold those positions to the last extremity.” The road to Centreville was jammed and “seemed to promise another Bull Run stampede,” wrote David Strother.

John Reynolds came with his two Reserves brigades to Henry Hill and took charge. Seizing a regimental flagstaff, Reynolds rode the full length of the battle line and back again, waving the banner and shouting “Forward, Reserves!” and blunting the Rebel advance. George Meade did not exaggerate in writing that when the Reserves “came into action, and held them in check and drove them back . . . we were enabled to save our left flank, which if we had not done the enemy would have destroyed the whole army.” Sykes’s regulars defended stubbornly, and Jesse Reno aggressively led reinforcements. In contrast, Robert Milroy, who disdained professional soldiers, completely lost his composure and was ordered by Colonel Buchanan of the regulars to “clear out and go away from here.” The Henry Hill defenders narrowly held their ground.

The battlefront now became one great confused melee. John Gibbon, whose brigade had been supporting Porter, wrote his wife of his surprise “to find that the enemy was moving in heavy force upon our left, and by his superior numbers & hard fighting was driving us before him. They seemed to advance in every direction. . . . The shot & shell tore thru’ the air, and the bullets whistled around our ears in a most astonishing way, but the feeling of personal fear seemed to be almost swallowed up by one of anxiety for the results of the battle. My men behaved splendidly & by their coolness and courage set a good example to some less inclined to be steady.” It was due to the coolness and courage of Gibbon and his like that the troops kept to their work.

Pope’s orders were now to fall back on all fronts, to re-form on Centreville. In the smoky dusk not everyone got the word. Lines of command and communication became tangled. One of Sigel’s batteries took Abner Doubleday’s brigade for the enemy and shelled it vigorously. Sam Heintzelman, trying to collect his Third Corps, narrowly escaped being hit on the firing line. “The troops did not fight well,” he noted in his diary. “It was evident neither officers or men had any confidence in Pope, nor much in McDowell. . . .” The best of the generals on the firing line—Reynolds, Meade, Kearny, Hooker, Reno, Stevens, Gibbon—managed to break clear of the enemy and withdraw in decent order.

McDowell assigned John Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade to the rear guard. Gibbon was posted on the Warrenton Pike, waiting for the rest of the army to pass, when Phil Kearny rode up to him. “He was a soldierly looking figure as he sat, straight as an arrow, on his horse, his empty sleeve pinned to his breast,” Gibbon wrote in his memoir. Kearny cautioned him to wait for his command, on the right, and for Reno, on the left. “He is keeping up the fight and I am doing all I can to help.”

In what Gibbon termed a very bitter tone, Kearny said, “I suppose you appreciate the condition of affairs here, sir?” At Gibbon’s inquiring look, Kearny repeated, “I suppose you appreciate the condition of affairs? It’s another Bull Run, sir, it’s another Bull Run!”

“Oh! I hope not quite as bad as that, General,” Gibbon said.

“Perhaps not. Reno is keeping up the fight. He is not stampeded. I am not stampeded, you are not stampeded. That is about all, sir, my God that’s about all!”

One of Jesse Reno’s Ninth Corps officers, Captain Charles F. Walcott, 21st Massachusetts, fresh from the stalwart defense of Henry Hill, had a vivid memory of that night retreat to Centreville. The first troops they met were from Franklin’s Sixth Corps, just arrived from Annandale, and he wrote, “Our hearts leaped with joy as we approached the long-hoped-for reënforcements from our Army of the Potomac. But to them we were only a part of Pope’s beaten army, and as they lined the road they greeted us with mocking laughter, taunts, and jeers on the advantages of the new route to Richmond; while many of them, in plain English, expressed their joy at the downfall of the braggart rival of the great soldier of the Peninsula.” Another witness, Carl Schurz, heard Franklin’s generals express “their pleasure at Pope’s discomfiture without the slightest concealment. . . .”

The men and officers of the Army of Virginia, along with their poorly grafted detachments from the Army of the Potomac, were tired and footsore and hungry, but rather than being demoralized like their counterparts at First Bull Run, they were angry and disillusioned. General Meade summed up these feelings in a home letter: “In a few words we have been as usual out-maneuvered & out-numbered and tho not actually defeated yet compelled to fall back on Washington for its defense & our own safety.” This was an army craving leadership.

From Centreville that evening Pope reported to Washington. “We have had a terrific battle again to-day,” he began, and described the enemy’s “massing very heavy forces on our left forced back that wing about half a mile.” Considering the men and animals were two days without food “and the enemy greatly outnumbering us, I thought it best to draw back to this place at dark. . . . The troops are in good heart, and marched off the field without the least hurry or confusion.” He believed the enemy crippled, and he closed, “Be easy; everything will go well.

Come Sunday morning, August 31, however, and John Pope offered General-in-Chief Halleck a darker, chilling vision. While he pledged to give “as desperate a fight as I can force our men to stand up to,” he issued a warning: “I should like to know whether you feel secure about Washington should this army be destroyed. I shall fight it as long as a man will stand up to the work. You must judge what is to be done, having in view the safety of the capital.”