The bombardment of the Belgian army headquarters at Mechelen had started on 18 October, as a result of which King Albert moved the headquarters to Antwerp. Once Mechelen was taken, the Germans moved their heavy guns forwards and began shelling the forts. The first German attack was directed against Sector 3. The strategy was to punch a hole in the defences of Sector 3 with the heavy guns, followed up by an infantry attack to cross the Nethe and Scheldt rivers. After that, the breach would be widened by the destruction of the forts in Sectors 2 and 4.

After the capture of Mechelen, the Germans advanced all along the line of Sectors 1, 2 and 4. They occupied Alost on the extreme left and Heyst-op-den-Berg on the right. The siege cannon were moved up into place and would concentrate on the forts in Sectors 1 and 3.

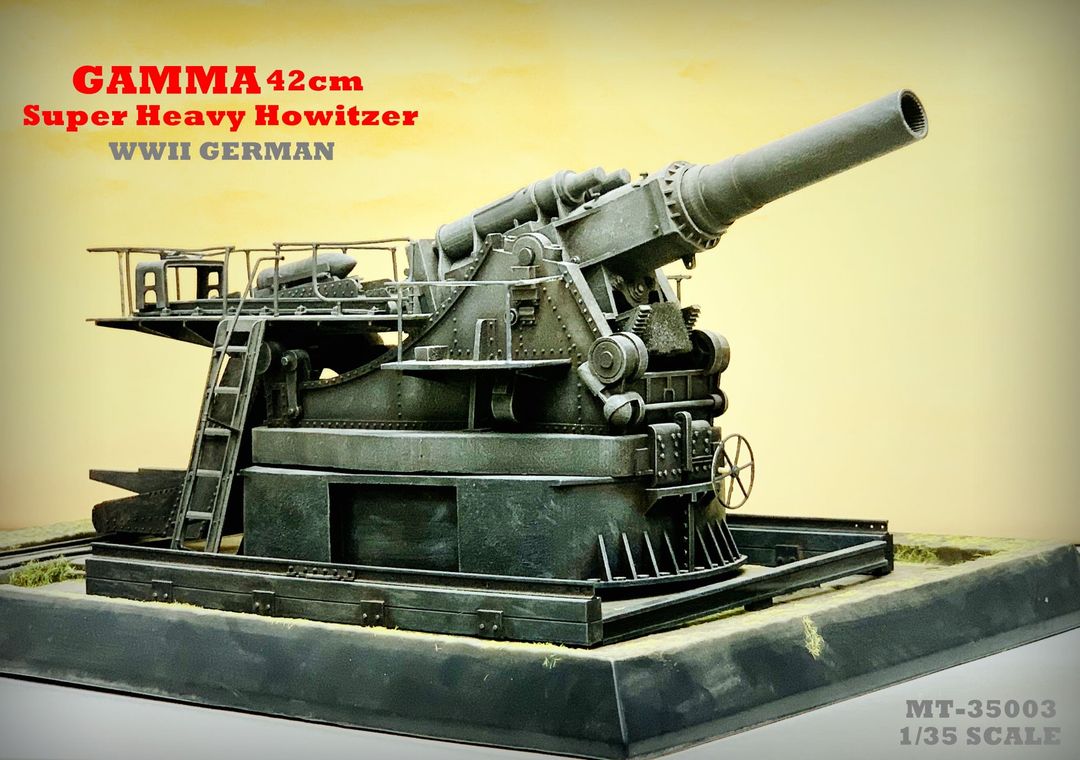

The first targets on 28 September were Forts Waelhem and Wavre-Ste-Catherine, using the 30.5cm and 42cm guns emplaced at Boortmeerbeek, about 10km south of the fortress line, at their maximum optimum range, as well as smaller-calibre guns. The effects were felt immediately in the forts, as the concrete cracked and fumes from the explosives spread throughout the tunnels. The 15cm turret of Fort Waelhem was put out of action and the telephone lines to the fort were cut.

On Tuesday, 29 September the Germans attacked Sector 4, pushing back elements of the 3rd and 6th Divisions some 1,500m from the main line. Then 30.5cm shells started falling on the entry bridge at Fort Breendonck. A German column reached Blaesveld bridge on the Willebroek Canal but was driven back by the defenders.

The bombardment of Fort Waelhem continued at the rate of ten shells per minute. The garrison fought to restore communications with headquarters, and all the fort’s guns remained operational (apart from the 15cm turret destroyed the previous day). The second 15cm turret was targeting the Mechelen–Louvain railway, where enemy activity had been spotted. At 1600 this turret was also damaged and put out of action. The ammunition magazine in the fort was hit and exploded, and seventy-five men inside the fort were badly burned. At 1830 the armoured observation post was struck, meaning the guns had to fire blind. During the night the guns were repaired and they continued firing in what they perceived to be the correct direction.

Fort Wavre-Ste-Catherine also suffered on the 29th. The turrets were destroyed one by one, and the garrison driven out of the shelters. At 1800 the fort was evacuated but the garrison would return later.

Captain Becker, commander of KMK 2, described the effects of the shells on Forts Koningshoyckt and Wavre-Ste-Catherine:

As shown by many photographs, the 42-cm shell was effective against the heaviest armour and concrete of the Belgian forts. As typical of this effect, I recall in particular two hits made by my own battery on the Fort of Wavre St[e] Catherine, in the outer line of forts of Antwerp, on 29 September 1914. On the morning of the 29th I fired with the second piece, the more accurate, at the heavy guns in the armoured cupolas, while using the first piece against the concrete casemates. On this day, I saw my eleventh shot strike fair upon the top of the cupola, where the enemy’s guns were actively firing. There was a quick flash, which we had learned at Kummersdorf [artillery proving grounds] to recognize as the impact of steel upon steel. Then an appreciable pause, during which the cupola seemed uninjured; then a great explosion. After a few minutes the smoke began to clear, and in place of the cupola we saw a black hole, from which dense smoke was still pouring. Half the cupola stood upright, 50 metres away; the other half had fallen to the ground. The shell, fitted with a delayed fuse action, had exploded inside.

The outlying defences also suffered terribly from the shelling. The interval redoubts and trenches were hit with the same violence as the permanent works. The forts provided supporting counter-battery fire whenever possible, but the forward observers were driven from their positions throughout the day and were no longer able to direct fire against the enemy. It appeared the Belgian defenders in the trenches would suffer the same fate as at Namur: pounded by unseen guns without any means of reply, and driven off their positions by unseen troops.

Despite Churchill’s promises, the Belgian leadership were not confident of rescue by the Allies, who were still 200km away. On the night of the 29th they concluded that since Antwerp was not as impregnable as they had originally thought, the field army should be quickly withdrawn, and saved to fight another day. The field troops were to be pulled back to the Dendre river to await the Allies, who were now approaching Arras. The evacuation was scheduled to begin on 2 October. The army supplies from the Antwerp warehouses would be transported first by rail to Ostend. The rail journey began at the Tête de Flandre on the left bank of the Scheldt, passed through St Nicholas and Ghent, and finally arrived at Ostend. The transports had to cross the railway bridge at Tamise, and to reach that they needed to cross the Willebroeck bridge – within range of the German guns. Despite the danger, the operation was completed under conditions of absolute stealth between 29 September and 7 October. The lines of retreat were defended by the 4th Division, deployed at Baesrode, Termonde and Schoonaerde. The cavalry was moved to Wetteren to guard the left bank of the Dendre, where the field army would take up position on 3 October.

The outlying defences also suffered terribly from the shelling. The interval redoubts and trenches were hit with the same violence as the permanent works. The forts provided supporting counter-battery fire whenever possible, but the forward observers were driven from their positions throughout the day and were no longer able to direct fire against the enemy. It appeared the Belgian defenders in the trenches would suffer the same fate as at Namur: pounded by unseen guns without any means of reply, and driven off their positions by unseen troops.

Despite Churchill’s promises, the Belgian leadership were not confident of rescue by the Allies, who were still 200km away. On the night of the 29th they concluded that since Antwerp was not as impregnable as they had originally thought, the field army should be quickly withdrawn, and saved to fight another day. The field troops were to be pulled back to the Dendre river to await the Allies, who were now approaching Arras. The evacuation was scheduled to begin on 2 October. The army supplies from the Antwerp warehouses would be transported first by rail to Ostend. The rail journey began at the Tête de Flandre on the left bank of the Scheldt, passed through St Nicholas and Ghent, and finally arrived at Ostend. The transports had to cross the railway bridge at Tamise, and to reach that they needed to cross the Willebroeck bridge – within range of the German guns. Despite the danger, the operation was completed under conditions of absolute stealth between 29 September and 7 October. The lines of retreat were defended by the 4th Division, deployed at Baesrode, Termonde and Schoonaerde. The cavalry was moved to Wetteren to guard the left bank of the Dendre, where the field army would take up position on 3 October.

On 1 October there was no let up in the heavy shelling. Fort Breendonck was shelled. Fort Kessel became a new target and the bombardment of Fort Lier continued with heavy shells falling every six minutes. The concrete around the 15cm turret was struck, displacing the turret and putting it out of action. The shells also produced heavy fumes that inundated the corridors and tunnels of the fort. The men could only sit and wait for the end. This time, however, the Germans were launching a pre-attack barrage. All along the Sector 3 line the Germans advanced, moving into the fortress line west of Wavre-Ste-Catherine and getting behind it and Fort Waelhem, forcing the final evacuation of Fort Wavre-Ste-Catherine. The 1st Division troops moved to reoccupy their evacuated trenches but the Germans were too strong. The 2nd Division was driven back to the Nethe river by artillery fire. Fort Koningshoyckt survived the attack but the Boschbeek redoubt was evacuated and at 1700 the central part of Dorpveld was seized. The Belgian garrison of Dorpveld became trapped in another part of the work.

The 1st Division was sent to the vicinity of Fort Lier to support the garrison’s riflemen. The men inside the fort, practically exhausted mentally from the effects of the bombardment and the destruction of the fort, were suddenly galvanized into action when they heard of the arrival of reinforcements and the news that the Germans were attacking. They rushed to the parapets and into the turrets and poured fire into the approaching Germans. An attack at 2100 was stopped, and two hours later a second attack was broken off. Attacks continued throughout the night in front of Fort Lier and on the Tallaert redoubt and between Forts Koningshoyckt and Lier. The fighting for the trenches was furious but the Germans retreated at 0200, having failed to break through the line. On 2 October the 1st and 2nd Divisions launched a counter-attack to retake positions lost along the trench line.

The garrison of Fort Waelhem continued to occupy the fort. They made repairs on 1 October and their guns remained operational, but the Germans believed the fort had been put out of action. A patrol approached the moat to see if anyone was left in the fort. They soon found out when Commandant Dewit ordered his men to open fire, scattering the Germans. The bombardment of the fort then resumed with greater intensity, destroying the bridge across the moat to the entrance. The defenders escaped across the rear moat using ladders. Fort Waelhem, despite a heroic defence, was finally in German hands.

In a frightening game of cat and mouse, the Belgian defenders of Dorpveld redoubt remained trapped in the wreckage while the Germans, in control of another section, hunted them down. Once they had located them, the Germans set off a mine in an attempt to finish off the garrison. Some of them escaped through a breach caused by the mine and fled across the fields. A second mine destroyed the redoubt, killing the remaining defenders.

At 1430 the magazine of Fort Koningshoyckt blew up, and the fort was finished. The Tallaert redoubt also exploded. The shelling of Fort Lier continued until it too was completely useless. Around noon the last turret was destroyed and at 1800 the garrison fled across the Nethe.

The Duffel redoubt had been pounded for four days, during which time the garrison made repairs whenever possible. The Germans, thinking that no further resistance was possible, set up a machine gun in the Wavre-Ste-Catherine railway station 700m from the fort and fired on the redoubt. They were surprised when a 5.7cm gun returned fire, driving the gunners away.

Most of the works on the south bank of the Nethe river had been destroyed. General de Guise decided to organize the defences to the north of the river. At this point the Belgian government notified the British of their intention to evacuate the field army from Antwerp and to use the fortress troops for the city’s defence. Winston Churchill immediately set out for Antwerp with the British Marines to persuade the Belgians to hold out a little longer.

On 3 October the Germans made another attempt to silence the Duffel redoubt. A German officer approached the redoubt with a truce flag. The defenders ceased firing but the officer was there simply to report his observations to the artillery batteries and the guns opened fire again. Duffel still held out but at 2200 the garrison ran out of ammunition and fled across the Nethe. Moments later the redoubt exploded. Likewise, the German batteries had continued to fire on Fort Kessel. Earlier in the day the three turrets were put out of action and the fort was evacuated.

Once all of the forts south of the Nethe had been destroyed or abandoned, the Germans prepared to cross the river. One attack was made on the Mechelen road at the railway bridge near Waelhem. Three attempts were made by German infantry against the approaches but each was repulsed. German engineers then decided to construct a temporary bridge across the Nethe near the village of Waelhem. They succeeded in putting together one bridge, but when the infantry advanced across it all the available Belgian guns were directed on it, causing major casualties. The bridge fell apart and the Germans retreated.

That evening the city’s spirits were lifted by the arrival of the first brigade of British marines, accompanied by Mr Churchill. The British troops included a brigade of Marine light infantry, approximately 2,200 strong, with several heavy guns. They had arrived by train from Ostend and were sent out to the Nethe front, where they were placed between Lier and Duffel. They relieved the Belgian 1st Mixed Brigade and supported the men of the 7th Belgian Infantry Regiment.

The morning of 4 October, the seventh day of the siege, was relatively quiet, but at around midday the German guns opened fire. The German artillery was being moved up towards the Nethe. The Belgians still held the trenches south of the Nethe, despite having lost the forts and redoubts. German shells now fell on these vulnerable positions, forcing the Belgians to flee across the Nethe, until the southern side of the river was completely in German hands.

The bombardment of the Nethe sectors continued all night and into Monday, 5 October, signalling an imminent infantry effort to cross the Nethe. The Belgian outposts were driven back and the Germans moved to the Nethe crossing points. German artillery fire pushed the defenders back even further from the river banks. Three German regiments crossed the Nethe at Lier but ran into the British troops defending the north side of the town. The British casualties were high but they held their ground and kept the Germans pinned inside the town. Here and there the Germans gained small bridgeheads on the north bank. In other locations they were pushed back by Belgian guns and infantry counterattacks. At around noon the 7th Line Regiment on the right flank of the British Marines was forced to fall back, exposing the British flank. A counter-attack by the 2nd Chasseurs, assisted by the British, regained the position.

The rest of the British reinforcements arrived on Monday, comprising two naval brigades with 6,000 men. Unlike the first group, these were mostly new recruits with little infantry training. Each brigade was composed of four battalions, and General Archibald Paris was in command.

In Sector 4 the 6th Division troops launched a counter-attack towards St-Amand. They reached and passed through the village but were met by a large German force and had to fall back. The Germans, meanwhile, bombarded Termonde and attempted a crossing of the Scheldt at Schoonaerde. A detachment of the 4th Division, guarding the approaches to the river, with artillery and cavalry support drove the Germans back, but the 4th Division’s position was becoming critical. A collapse would open the door for the Germans to march south of Antwerp and outflank it from the west, sealing in the Belgian and British defenders.

At 0200 on 6 October a surprise attack was launched by the Belgian 21st Line Regiment and two chasseur regiments from the 5th Division, making a bayonet charge against the German-held trenches. After the attack started, the Belgians heard cries of ‘Friend, English,’ coming from the trenches and they halted, unsure of what to do. Finally figuring out it was a ruse, they rallied and moved forwards. Hand-to-hand combat ensued in the dark and the Germans were pushed back to the Nethe. The Germans replied all along the line with machine guns and by daybreak the battle was over. The Belgians pulled back beyond Lier. This was the last allied offensive of the battle.

During the day German troops poured across the Nethe and moved towards the city. The Belgians pulled back to their secondary lines of defence. The British had mounted their heavy guns in the Brialmont forts and their shells now began to fall on the Germans. In the afternoon Fort Broechem fell, widening the gap to 20km. German attempts to cross the Scheldt were relentless. The Belgian command realized that the evacuation must begin now, and had to be done quickly.

Meanwhile, the French and Germans continued to move towards the channel ports. In early October the Germans had reached Lille and were moving rapidly to cut off the Belgian army. They were just 60km from Nieuport, while the Nethe was some 140km away. It was important for the Belgians to move as quickly as possible to Ghent to guard the lines of retreat to the west. They requested British reinforcements at Ghent as quickly as possible and the British government promised to send the 7th Infantry Division. The French also marched to the area at full speed.

On the night of 6 October King Albert ordered the Belgian field army to move to the left bank of the Scheldt. As we have seen, the army supply trains had already successfully reached Ostend. The Belgian army was to cross over the bridges at Tamise, Hoboken and Burght, and then move westwards. The defence of Antwerp would then be handed over to the 30,000 fortress troops, plus the 2nd Division and the three British brigades. The retreat began at midnight. The 1st and 5th Divisions moved first across the Scheldt near the Antwerp docks; 3rd Division crossed further north. The troops that were left to defend the city after the withdrawal of the field army quietly pulled back to man the defences adjacent to the inner circle of forts. The Germans had by now moved their guns north of the Nethe and began to shell the old forts, beginning with Fort 1.

On 7 October the Belgian government left the city by boat for Ostend; Churchill left at the same time. When the Belgian citizens of Antwerp discovered that the government had left, there was widespread panic, which resulted in the mass exodus of civilians from the city by all means available, both to the west and to the north into Holland. King Albert left at 1500 with his army. The 2nd Division, the fortress troops and the British forces continued to hold the second line of defence.

The Germans finally crossed the Scheldt at Termonde, Schoonaerde and Wetteren in the afternoon. At Schoonaerde the crossing was in force. The vanguard of three cavalry regiments advanced as far as Nazareth, 12km from Ghent.

On the night of the 7th the bombardment of Antwerp began in earnest, in order to compel the governor to surrender the rest of the operational forts. The Germans used incendiary bombs, and buildings all across the centre of town went up in flames. The Belgians set fire to the petroleum tanks at Hoboken, sending thick oily smoke 200ft into the air. Bombs fell all night long and the destruction was terrible. Belgian engineers contributed to the destruction by sabotaging everything in sight that could be useful to the Germans – gas pipes, electrical lines, warehouses and bridges – and ships were scuttled to block the harbour.

On the 8th the German III Reserve Corps, reinforced by the 26th Landwehr Brigade, occupied the ground in front of Forts 1 to 6 and the forts’ defenders were swept by German machine guns. At around 1730 General Paris decided it was time to move his troops out under cover of darkness. General de Guise agreed. The British moved first, followed by the Belgian 2nd Division. The naval brigade left last, at around 1930. Several units passed through the city and crossed the Scheldt. One battalion of the 1st Naval Brigade, the 2nd Brigade and the Marine Light Infantry covered the retreat and then marched west all night, finally catching a train to St-Gilles-Waes. Further along, the rails had been cut and these units, harassed by German patrols, fled across the Dutch border. Some made it to Ostend.

Three battalions of the 1st Naval Brigade, together with the Belgian fortress troops in front of Forts 1 to 4, received the news of the retreat much later than the others, and it wasn’t until 9 October that they passed through Antwerp towards the river. The bridges had already been destroyed. Some of the units found rafts to cross the river; others headed north to Holland.

On the evening of Thursday, 8 October General de Guise finally left the city and crossed the river to Fort Ste-Marie. He would eventually surrender to the Germans there on Saturday morning. The Belgians were the last to leave Antwerp, despite offers from General Paris for the British to guard the retreat. On Friday, 9 October most of the remaining forts of the first line gave up. Fort Merxem was sabotaged, as was the Dryhoek redoubt. The guns and electrical generators of Fort Brasschaat and Audaen redoubt were destroyed and those works vacated. Fort Liezele and Breendonck also surrendered.

Later in the day a delegation from the town sought out the Germans to surrender the town. At around noon the first Germans entered Antwerp: it was the start of a four-year occupation. The forts still remaining in Belgian hands were sabotaged and evacuated: Forts Schooten and s’Gravenwezel at 1430, followed by Fort Ertbrand, the Smoutakker redoubt and Fort Stabroeck. The commander of that last fort refused to leave and was killed in the explosion to sabotage the fort. The garrison troops in Sector 5 moved towards Holland. In all, 400 officers and 35,000 men of the Antwerp garrison were interned in Holland. The British lost 37 killed, 193 wounded and 1,000 missing, of whom 800 were captured by the Germans. Some 1,560 were interned in Holland. Of the 1st Naval Brigade, only one-third of the men returned to England.

In the evening of Friday, 9 October the mass of the allied army crossed the Terneuzen Canal and the British divisions arrived at Ghent.